|

The e-mail survey on cataract surgery was opened by 1,583 of 10,000 subscribers to Review’s electronic mail service (16 percent open rate) and, of those, 142 filled in their answers.

High-tech Techniques

The 23 percent of respondents who are using the femtosecond say they’re experiencing various benefits from it.

“It’s good for Fuch’s, zonular instability, mature cataracts and the treatment of low amounts of astigmatism,” says Chambersburg, Pa., surgeon David Ludwick. “It results in a much higher percentage of patients with 20/20 or 20/25 postop uncorrected visual acuity.” Another surgeon, who wished to remain anonymous, says it creates a better central continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis and “its nuclear fragmentation reduces phaco energy.” One surgeon says he’s very likely to begin using the femtosecond in the coming year. “I want to offer it as a learning option for our residents,” he says. “I look forward to its use in limbal relaxing incisions.” John Sheppard, MD, of Norfolk, Va., uses the femtosecond laser for everything from the entry wound and capsulorhexis to nucleus fragmentation. “It gives precise wound management,” he says. “It’s high-tech, a practice builder and fun.” But he adds that it also has drawbacks. “Its expensive, and it slows surgery,” he says. “Also, cortex extraction is difficult.”

|

Scott Corin, MD, of Dartmouth, Mass., is also looking for results before changing his way of operating. “A $500,000 machine to do what two $15 blades and a $300 forceps can do just as well?” he opines. “It is all marketing and zero science.” A surgeon from Nebraska hopes that there’s more than marketing to the technology. “There’s been no proven benefit in peer-reviewed studies,” he says. “I have major concerns about our profession being driven by industry and greed as opposed to demonstrated patient care and improved outcomes. Femto is a very ‘cool’ technique, but it requires increased OR time, increases health-care expense and until good data exists to demonstrate patient benefit, should not be promoted as providing it. It will undoubtedly improve over time and may very well become standard of care if demonstrated benefits for patients are shown in the future.”

Turning toward other cataract surgery technology, surgeons also weighed in on intraoperative wavefront aberrometry. Only 9 percent say they currently use it, and 75 percent of the non-users say they’re unlikely to begin using it in the coming year. Most of the reasons given for not adopting it relate to either cost/benefit ratio or a surgeon’s facility just not springing for it.

“The startup cost [is one reason],” says a surgeon from Arkansas. “And it gives a 2 to 3 percent increase in postop refractive prediction outcome when my outcomes are at 96 percent already. Patients are happy, and I’ve got excellent outcomes in a wide range of patients.” Juan Nieto, MD, of Dubuque, Iowa, is in the same boat, saying, “I’m not convinced that it will improve on my outcomes.” A surgeon from Arizona also feels it might be overkill. “I can’t remember the last time I had a refractive surprise using conventional measurements preop,” he says. One surgeon from Alabama speaks for a group of surgeons who might like to use it but their facilities won’t invest in it. “My hospital won’t buy it,” he says. One surgeon from New York thinks the method by which the device gets its data might give him problems. “It’s a waste of time,” he says. “The results are not good if the cornea is starting to swell.” Finally, a surgeon from Baltimore succinctly sums up many of his colleagues’ doubts by saying, “I don’t feel the juice is worth the squeeze.”

|

Finally, Robert Lehmann, MD, of Nacogdoches, Texas, says it feels as if history is repeating itself as new technology comes on-line. “For those who think the femtosecond laser and intraocular aberrometry aren’t valuable,” he says, “remember LASIK before femto and planned ECCE before phaco!”

Astigmatism Management

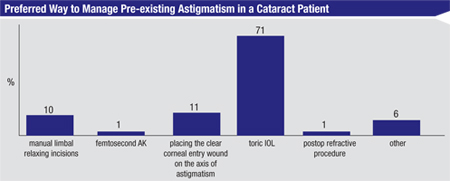

Toric IOLs continue to hold sway in terms of treating a patient’s astigmatism, with 71 percent of the respondents saying toric lenses are their preferred method. Ten percent prefer manual limbal relaxing incisions, 11 percent like to place the clear corneal entry wound on the astigmatic axis, 1 percent use a postop refractive procedure and another 1 percent use femtosecond astigmatic keratotomy. Six percent say they choose some other method.

“Toric IOLs give excellent results and add little complexity to the procedure,” says a surgeon from New Jersey. “Arcuate incisions are less consistent and can exacerbate dry eye.” A surgeon from New York thinks lenses yield the best results, saying, “They’re an accurate method to fix most levels of astigmatism.”

For the surgeons who prefer manual LRIs, though, they think they’re the right tool for the job. “Using manual LRIs, I can control the astigmatism quite well,” says Christopher Papp, MD, of South Lyon, Mich. “And, it’s cheaper for the patient and the medical system in general.” A surgeon from Oregon also appreciates the cost-effectiveness of incisions. “They work,” he says. “And they’re not dependent on expensive equipment.”

Some surgeons, though, will segment their astigmats based on the level of their astigmatism, and choose a procedure based on that. “Toric IOLs are effective for larger amounts of astigmatism,” says a surgeon from Maryland. “I also uses manual LRIs, femto AKs, incisions on the steep axis and occasionally an in-office LRI.” Russell Wolfe, MD, of Hollywood, Fla., says he starts with spectacles and works up from there. “I most commonly treat astigmatism with glasses,” Dr. Wolfe says. “For small amounts I recommend arcuate femtosecond keratotomy, and for larger amounts, the toric IOL.” Ivan Mac, MD, of Charlotte, N.C., says the amount of astigmatism makes the difference for him. “For patients with up to 1.5 D, femtosecond AK is very accurate,” he says. “Over this level, I prefer toric lenses.”

Cracking the Nucleus

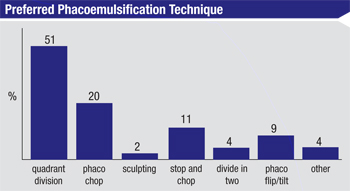

For attacking the cataract, 51 percent of surgeons prefer quadrant division, a fifth like phaco chop, 11 percent use mainly use stop-and-chop and 9 percent like phaco flip/tilt. For the rest, 4 percent divide the nucleus into halves, 2 percent perform sculpting and 4 percent choose some other method.

“I’m ambidextrous,” says a surgeon from Texas who prefers quadrant division. “So, I can sculpt, rotate, sculpt, phaco the quadrant, rotate, chop and then chop/phaco the remaining pieces. My hands are at 3 and 9 o’clock.” A surgeon from Florida thinks quadrants work best in terms of safety. “The quadrant size is more manageable for phaco within the bag,” he says, “thus keeping the ultrasound power farther away from the endothelium.” A surgeon from Connecticut says quadrant division is “quick, safe and simple.” Dr. Lehmann explains why quadrant division is so popular. “It’s efficient,” he says. “I groove, split in half, then crack the first half into quarters. Then, the second half is removed without further cracking.”

The surgeons who like phaco chop think it has strong points, as well. “It’s efficient, versatile, minimizes phaco time and the risk of capsular issues, and is friendly to the endothelium,” says a surgeon from Georgia. Florida’s Dr. Wolfe says, “I find that phaco chop is efficient, allowing the removal of various densities of cataracts with relatively low phaco times.” Another surgeon from Georgia likes phaco chop’s versatility. “I can use horizontal chop for any cataract hardness,” he says. “The second instrument tip is blunt for capsular protection, and I use less phaco power than with divide and conquer.”

|

Preventing Infection

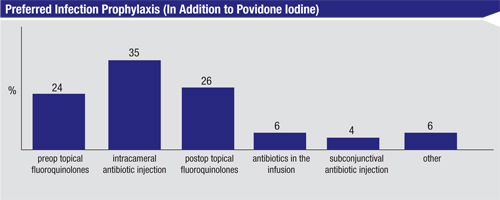

In recent years, data on antibiotics in the infusion has led to debates about the best way to prevent infection with cataract surgery (aside from the use of povidone iodine). Thirty-five percent of the surgeons on our survey say that they think intracameral antibiotic injection is best, followed by 26 percent who prefer postop topical fluoroquinolones, 24 percent who like preop topical fluoroquinolones, 6 percent who put antibiotics in the infusion line and 4 percent who prefer subconjunctival antibiotic injections. Another 6 percent say they prefer to use some other method of infection prevention.

“I also irrigate the fornices with copious amounts of BSS after draping and before starting surgery,” says a surgeon from Illinois. “I suspect decreasing the bacterial concentration in the conjunctival fornices is helpful in lowering the risk of infection.”

Surgical Pearls

In addition to commenting on specific aspects of cataract surgery, surgeons also provided their top surgical pearls for getting the best, safest results.

“I use conjunctival pledgets in the superior and inferior fornices soaked in lidocaine and marcaine for five minutes prior to surgery,” says Carol Johnston, MD, of Jacksonville, N.C. “I rarely need any intraocular lidocaine unless using a Malyugin ring or a very deep chamber in a post-vitrectomy eye. Next, I use traction sutures at the site of my pledgets, which gives me great exposure and avoids dealing with eye movement and Bell’s phenomenon in patients.”

Since intraocular floppy iris syndrome is such a problematic complication, Dr. Fry takes steps to prevent it. “Use intracameral Shugarcaine in all Flomaxers and in all small pupils,” he says. “You never know who has been exposed to alpha-1a blockers.” Robert Bahr, MD, of Providence, R.I., says a possible change in technique might prove to be safer. “One-handed phaco avoids leakage from the sideport incision,” he says. “And, it provides a far more stable anterior chamber as well as contact with nuclear material.” A surgeon from Iowa says managing astigmatism is one of the keys. “Always do what you can to keep the postop astigmatism under 0.5 D,” he says. “Also, do a Mackool incision with premium lenses that might need a follow-up LASIK for residual astigmatism.”

Finally, if the stresses of a complicated cataract surgery case begin to get to you, Kentucky’s Dr. Ballard says it helps to take a philosophical approach to things. “Relax,” Dr. Ballard says. “You could have been an OB-GYN.” REVIEW