Therapeutic Cross-Linking

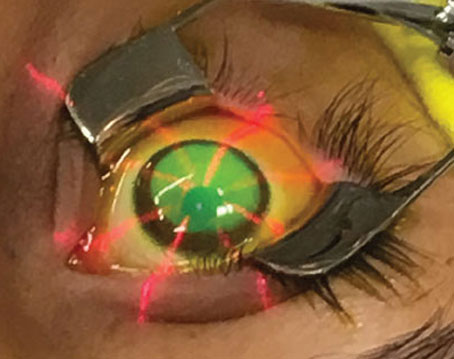

To get an idea of cross-linking’s baseline procedure, the cross-linking approach as originally formulated involves first debriding the epithelium, then instilling 0.1% riboflavin in 20% Dextran over a period of 30 minutes. Then, the riboflavin-laced cornea is irradiated by UV radiation at a power of 3 mW/cm2 for 30 minutes, while adding a drop of the riboflavin solution every five minutes. Studies have found that this approach arrests the progression of keratoconus in a large majority of eyes, and decreases corneal steepness by as much as 5 D.1,2 Experts anecdotally estimate that this approach is still used by about half of the practitioners in the world.

|

A popular approach to accelerated cross-linking on the international scene, and which is currently under Food and Drug Administration evaluation in the United States, is the Avedro VibeX/KXL treatment. Bogota, Colombia, surgeon Gustavo Tamayo has performed 1,900 procedures with the system—on both keratoconus and postop ectasia patients—and says he thinks its accelerated approach to cross-linking will become popular.

“I’ve been using the Avedro system since 2011, but I’ve been doing cross-linking since 2006, when I started using the German IROC system,” Dr. Tamayo says. “I switched to the Avedro system for several reasons. First, it’s faster. This system takes six to 10 minutes per eye. Second, it was developed based on a concept with which I heartily agree: You don’t need riboflavin anywhere but the first third of the anterior stroma. Going deeper, I feel, doesn’t work better and in fact may result in the loss of more keratocytes. Using the IROC system, I started to see a little bit of damage in the posterior third of the stroma in the form of low-grade haze, which resulted in slow visual recovery, some eyes taking longer than six months to get back to their preop BCVA. I believe the reason for the haze was was too much riboflavin in the deeper corneal layers.”

Avedro was able to perform adequate cross-linking in less time by modifying both the riboflavin and the energy used. The special riboflavin is called VibeX Rapid, and consists of 0.1% riboflavin without Dextran, to enable rapid uptake. “In addition, they use a high-power UV system,” adds Dr. Tamayo. “So, instead of doing 3 mW for 30 minutes, they use 30 mW for three minutes. Ultimately, this higher power for a shorter time ends up delivering the same total power: 90 mW and 5.2 mJ to the cornea.”

Though Dr. Tamayo hasn’t analyzed all 1,900 patients yet, he can share his overall clinical impressions. “None of the eyes that I’ve treated with this system has developed any recurrence of the ectasia, and I’ve been able to stop the progression of the cone in all of them,” he avers. “Currently, it’s working without the haze, the ulcers or the delay in recovery of vision that I had in some cases with my previous unit. Some patients may have had a delay in re-epithelialization, but no one has lost any lines of best-corrected vision or has lost endothelial cells. However, if someone were to say that two years of follow-up may be too short to say whether a cross-linking system is working or not, I’d have to agree.”

In the United States, Avedro is involved with two studies. The first, which is currently in the data-analysis phase, is studying accelerated cross-linking. It compares the procedure to a sham-treatment group. “The early response patterns show a relatively homogeneous and deep cross-linking effect,” says Peter Hersh, MD, Avedro’s medical monitor. “The eyes show the expected stromal haze and the OCT shows deep demarcation lines, as one would expect after cross-linking.”

The second study uses Avedro materials, and is sponsored by the American-European Congress of Ophthalmic Surgery. This study will include as many as 2,000 eyes with keratoconus and 2,000 with postop ectasia, and will randomize them among three groups: 15 mW light; 30 mW light and 45 mW light. The ACOS study’s recruitment phase is currently under way.

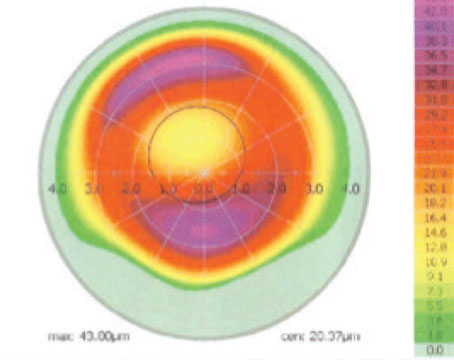

In terms of selecting patients for cross-linking, surgeons have recently made strides on that count, as well. John Kanellopoulos, MD, a surgeon from Athens, Greece, who has been at the forefront of many advances in cross-linking, says that his group has found that visual acuity and corneal thickness are actually poor indicators of the degree of irregularity in the cornea.3 “We feel that the data is compelling that corneal regularity indices of the sort provided by many topographic devices are far more sensitive and reliable in picking up the clinical degree of keratoconus and its progression,” he says. “In [our] paper, we reviewed over 700 patients through five years of follow-up, and measured all clinical parameters such as UCVA and steepest Ks, as well as eight topometric parameters on the Pentacam. We found that the two most significant red flags for picking up keratoconus or its progression were the index of surface variance and the index of height decentration. Visual acuity was irrelevant. Again, this was in a group of young keratoconus patients, a group that I feel needs the most attention, because older keratoconus patients don’t change much.”

Cross-Linking Plus PRK

Another wrinkle surgeons have added to cross-linking is the inclusion of simultaneous topography-guided surface ablation. The concept was first introduced by Dr. Kanellopoulos and has become known as the Athens Protocol.

“Though cross-linking has been found to be successful in the literature, the problem is that patients who can’t tolerate rigid gas permeable lenses, are still left with an extremely irregular optical system,” explains Dr. Kanellopoulos. “So we introduced the concept of using the excimer laser to remove 20 to 30 µm of tissue. At first blush, ablating like this might seem undesirable in a cornea that’s already thin, but the advantage is great: Not only does the cornea appear to be stable afterward, but it seems to be far more visually competent.”

|

Dr. Kanellopoulos performed a prospective study of 412 Athens protocol patients to analyze the safety of the procedure, as well as to get a sense of cross-linking’s complications in general. The complications were as follows:

• 30 percent reported severe pain on day one postop, 25 percent reported moderate pain and 45 percent had no significant pain;

• 75 percent had delayed epithelial healing by day six, and 10 percent had delayed healing by day 10;

• 25 percent had transient epithelial scarring that lasted for a month;

• at six months, 12 cases (2.9 percent) had subepithelial corneal scarring that didn’t affect visual function;

• transient stromal haze occurred in 15 percent of cases, but 95 percent of them resolved by month six;

• there were eight cases (1.9 percent) of persistent haze past month six and one case of late stromal haze (0.2 percent) occurring at one year postop with intense sunlight exposure, which subsequently responded to a six-month course of Lotemax; and

• seven (1.6 percent) showed ectatic progression, four of which needed additional cross-linking (0.9 percent).5

Epi-On vs. Epi-Off

Since performing cross-linking the traditional way involves debriding the epithelium, with its attendant issues as the cornea re-epithelializes, some surgeons have taken to performing cross-linking through the epithelium, leaving it intact. This approach may also help in corneas that are a shade too thin for epi-off, they say. The approach may involve trade-offs, however.

Leopoldo Spadea, MD, associate professor at the University of L’Aquila in Italy, has seven years of experience with epi-off and four years of experience with epi-on treatments, and has discovered some things about them along the way. “Epi-on is a less-invasive technique, with less pain, a faster recovery period and faster healing, but less efficacy,” he says.

To promote the penetration of riboflavin, Dr. Spadea says he uses a special formulation called Ricrolin TE (Sooft, Montegiorgio, Italy), which he instills every 10 minutes over a two-hour period. After instilling a topical anesthetic and pilocarpine to constrict the pupil in an effort to prevent UV damage to the lens and retina, he instills five more drops of riboflavin over a 15-minute period. Then, he irradiates the cornea for 30 minutes with 3 mW/cm2 of radiation, all the while instilling riboflavin at five-minute intervals.

“I’ve found epi-on’s efficacy to be one-fifth of the epi-off technique,” he says. “It’s a good technique, just less effective. With epi-off, the efficacy is more evident. The demarcation line—a gray line inside the cornea that shows where the radiation treatment has reached—is very deep with epi-off, but with epi-on it’s very superficial. With epi-on I can obtain an average reduction of the apex of the cone of around 1.5 D, sometimes as much as 2 D. With the epi-off technique, the reduction of the apex of the cone is between 4 and 5 D, and these results are more consistent and easier to obtain.

“I have had some patients in whom one cornea was thicker than the other,” Dr. Spadea continues. “In the thinner cornea we performed the epi-on technique; with the thicker, the epi-off. The refractive result was more evident in the epi-off technique, with an increase in both BCVA and UCVA.”

Dr. Spadea says the best candidate for epi-on in his practice is someone in whom the cornea is less than 400 µm. “That’s the most important indication for me,” he says. “It also makes it easier to perform cross-linking on children. However, in an older, cooperative patient in whom the cornea is greater than 400 µm, for me, currently, the epi-off technique is better.”

The multicenter CXL-USA cross-linking study has made epi-on cross-linking its procedure of choice for FDA trials, and its investigators have reported good efficacy. In its study of 181 patients who underwent epi-on cross-linking, the average cylinder decreased from 4.52 to 3.96 D. Also, the average 2-mm K astigmatism on Pentacam decreased from 5.47 to 4.66. Forty-six percent of the eyes gained one or more lines and 36 percent had no change in their BCVA. Thirty percent lost one or more lines. The average follow-up was 10.9 months. (Rubinfeld R, et al. IOVS 2012;53:ARVO E-Abstract 6786)

Cross-Linking Plus LASIK

As a hedge against possible ectasia, some surgeons are adding a cross-linking treatment to their LASIKs.

|

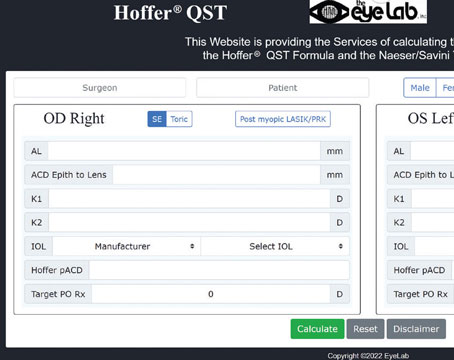

Before he adopted the procedure, though, Dr. Tamayo wanted to make sure the cross-linking didn’t interfere with the LASIK, so he conducted a study in which he performed LASIK Xtra in one group of patients and LASIK in another group. “At one month, my results were the same,” he says. “There were no changes in UCVA or BCVA. Since it didn’t change the LASIK, I developed some indications for it, all for patients with normal corneas: The first is young patients, 21 to 23 years old. The next is for patients who are heavy eye-rubbers. And third, I will use it in high myopes. In these patients, even though they have normal corneas, the fact that I did a large, deep ablation in addition to creating a flap, I see no reason not to use cross-linking for them. I must note, though, that LASIK Xtra isn’t intended for patients at high risk for developing ectasia. In such cases, I think the surgeon should choose a procedure without a flap.” Dr. Hersh says that Avedro plans to launch a U.S. clinical study of LASIK Xtra combined with hyperopic LASIK for patients with +2 to +6 D of hyperopia late in 2013.

Cross-Linking in Children

Surgeons say that, even though very long-term data is lacking, cross-linking appears to be a helpful treatment for young patients with keratoconus when preceded by appropriate discussions with the patient and the parents.

A two-year study from Europe composed of 48 eyes of patients aged 4 to 18 (mean: 13.7) found that the patients’ logMAR UCVA improved significantly, from 0.81 to 0.61 (p<0.05), and their BCVA improved from 0.43 to 0.21 (p<0.05). Topography showed a statistically significant reduction of mean simulated K in the flat meridian from 46.35 to 45.28 D (p<0.05). The researchers say that these positive results are promising for pediatric patients, since they are the group that endures the most dramatic keratoconus progression if left untreated. (Epstein D, et al. IOVS 2013;54:ARVO E-Abstract 5267)

When faced with a pediatric keratoconus patient who might benefit from cross-linking, Dr. Tamayo says, “The first thing I tell the parents is that it may not work.” He then briefs them on the possible pitfalls. “First, if the cone developed due to heavy eye rubbing in a 7-year-old, for instance, which is the youngest patient I’ve done cross-linking on, and the rubbing continues, even cross-linking may not stop the damage,” he says. “Second, the patient and parents should know that there’s a large possibility of having to repeat the procedure again in six or seven years. Third, I inform them that I’m not doing a refractive correction, so the patient may still need glasses or contact lenses afterward.” He says the 7-year-old, whose mother had undergone bilateral corneal transplants due to keratoconus, is stable at two years.

As far as age limits, Dr. Tamayo thinks 6 might be the youngest age possible for cross-linking simply due to the ability to successfully analyze a child of that age with elevation topography. He says most of his pediatric patients are between 12 and 16. “That’s the time when I, the parents and the patient start to see the astigmatism increase almost every six months,” Dr. Tamayo says. “We can see the cone developing, so that’s when I go to cross-linking right away.” REVIEW

1. Coskunseven E, Jankov MR, Hafezi F. Contralateral eye study of corneal collagen cross-linking with riboflavin and UVA irradiation in patients with keratoconus. J Refract Surg 2009;25:4:371-6.

2. Raiskup-Wolf F, Hoyer A, Spoerl E, Pillunat LE. Collagen crosslinking with riboflavin and ultraviolet-A light in keratoconus: Long-term results. J Cataract Refract Surg 2008;34:5:796-801.

3. Anastasios JK, Asimellis G. Comparison of Placido disc and Scheimpflug image-derived topography-guided excimer laser surface normalization combined with higher fluence CXL: The Athens Protocol, in progressive keratoconus. Clin Ophthalmol 2013;7:1385-96. Epub 2013 Jul 18.

4. Kanellopoulos AJ. Comparison of sequential vs. same-day simultaneous collagen cross-linking and topography-guided PRK for treatment of keratoconus. J Refract Surg 2009;25:9:S812-8.

5. Kanellopoulos AJ, Cho MY. Complications with the use of collagen cross-linking. In: Agarwal A, Jacob S, ed. Complications in Ocular Surgery. Thorofare, N.J.: Slack, 2013. 115-20.