In his course on transitioning from Descemet’s stripping endothelial keratoplasty to Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty, Dr. McKee uses this case as an example of the sinister phenomenon known as negative transfer, where a skill or maneuver that used to be useful in one task is now actually detrimental in a new one. “You have to be careful when you transition from DSEK to DMEK,” Dr. McKee says, “and not take some of those skills that worked well for DSEK and try them in DMEK where they won’t work so well.”

With that in mind, in this article DMEK experts offer advice on making the transition from DSEK to DMEK, give their best pointers for succeeding with the tricky parts of DMEK and even point out areas where your DSEK skills will hurt you in DMEK.

Preop Considerations

Surgeons say there are some steps you can take preoperatively to ease the transition and make your first cases manageable.

• Patient selection. Dr. McKee, who works with DMEK guru Francis W. Price Jr., MD, at the Price Vision Group, says that especially for a beginner, DMEK works well in patients who still have their vitreous and have an intact hyaloid face.

|

• The donor tissue. Because of the nature of the donor tissue that’s placed in the eye, DSEK and DMEK start to diverge at this point. “For myself, I don’t pay too much attention to the age of the donor tissue for DSEK,” says Albert Jun, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology at Johns Hopkins’ Wilmer Eye Institute. “Even though I acknowledge that the corneal donor study indicated that donor age wasn’t a huge factor, in endothelial cell survival, at least, for DMEK I do pay attention to the donor age. In terms of how the donor handles during surgery, it turns out that tissue from older donors is both easier to prepare and to handle. For DMEK, I know that if I get a donor who is under 50—which is something of an arbitrary cutoff—then I may have more difficulty in surgery. The younger donor tissue will be just more difficult to unfold in the recipient’s eye.”

In terms of preparing the donor tissue, Dr. Jun says it might be best for the beginning DMEK surgeon to take a page from the DSEK surgeon and let the eye bank prepare it. “DSEK really took off after eye banks became involved with tissue preparation,” Dr. Jun says. “And if someone’s really serious about doing DMEK, at least in the United States, he should have the tissue prepared at an eye bank. This is one of the things I tell people in lectures on making the transition from DSEK to DMEK: You could prepare the DMEK endothelial graft yourself, but why would you? By having the eye bank do it, you take the donor preparation part of the procedure—which involves extra time and stress—completely out of the equation. It’s just another variable, and a substantial one, that you won’t have to be concerned with.”

Dr. McKee, however, thinks it’s a good idea for the beginner to prepare the donor tissue. “It teaches you to work with Descemet’s membrane while you learn to prepare the tissue,” he avers. “To prepare the tissue, one of the things you’ll need is a microdissector. Mastel makes the one I prefer to use, called the Microfinger. Moria also makes one.

“Though there are different ways to approach preparing a graft, the one we use is called the ‘submerged cornea using backgrounds away’ technique that Art Giebel, MD, developed,” Dr. McKee continues. “In the SCUBA technique, we keep the donor cornea submerged in a viewing chamber and score the peripheral edge of Descemet’s near the trabecular meshwork. Then, we use the Microfinger to elevate an edge and make sure there are no radial tears. Once the edge is elevated, we use small Tubingen forceps to carefully peel about 90 percent of the graft, leaving just the center of Descemet’s attached. Then we do a trephination that’s the size of the graft we want, and pull off all the peripheral Descemet’s that’s been touched. That leaves a central 8- or 9-mm graft that’s not been touched and is only attached to the cornea with a 1-mm square area in the middle. At that point, touching just one part of the graft on the very edge, we pull off that 1-mm square bit and the entire graft comes free and curls up like a scroll.”

Intraoperative Issues

It’s during the surgery itself that the differences between DSEK and DMEK become even greater, especially when it comes to working with the fragile DMEK graft.

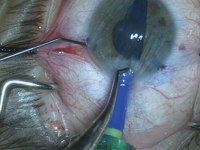

• Host preparation. There are differences in preparing the recipient cornea that the DSEK surgeon will need to take note of. “The technique for stripping the host cornea is the same technique as in DSEK,” says Dr. McKee. “However, in DSEK, most surgeons will strip a little bit smaller than the planned size of the graft so they don’t get any peripheral edema where there’s no coverage of the cornea. But in DMEK, any retained Descemet’s will actually repel the DMEK graft. So, for DMEK, we strip the same size or maybe even a little bigger than the donor size.”

Chicago surgeon Thomas John says that it can be challenging working on the inner dome of the DMEK host cornea using just a straight instrument, so he developed a curved instrument called the Dexatome as part of a set of DMEK instruments from Storz/Bausch + Lomb.

| ||||||

Dr. McKee adds that one particular maneuver that may have been useful in DSEK is now the opposite in DMEK, in his opinion. “A couple of years ago, Mark Terry described how roughening the peripheral stroma in the area where you’re going to place your DSEK graft might help the graft adhere better,” Dr. McKee says. “But that’s an absolute no-no with DMEK, because the stromal fibers are soft in the posterior cornea. If they were to get roughened, they’d stick up from the back of the cornea and prevent the DMEK graft from adhering flat.”

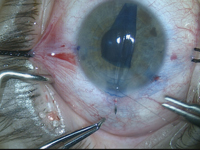

• Injecting the donor tissue. If the surgeon didn’t prepare his own graft tissue, then this part of the procedure may be the first encounter he’ll have with the super thin, 12- to 15-µm thick DMEK graft. The differences between it and the thick DSEK graft will be stark. “The DSEK graft is more like a lenticule or a disk,” says Dr. McKee. “The DMEK graft is just a scroll. The DSEK lenticule has mass to it, and wherever you put it is where it will stay. The DMEK scroll, though, is virtually weightless. As a result, the scroll will flow like water. Like a jellyfish, wherever the fluid current goes, the scroll will follow. It can maneuver its way around sutures, out of paracenteses, through peripheral iridotomies, behind lenses and even into the back of the eye in an aphakic patient. You have to be gentle and understand fluid dynamics.”

Before inserting the graft into the eye, Dr. John likes to stain it with trypan blue ophthalmic solution (Vision Blue, DORC) to aid visualization. For this he uses a small block with two wells from his DMEK instrument set. “When you try to stain the membrane and then use a Weck-Cel sponge on the fluid in a conventional concave well, the Descemet’s membrane is attracted to the sponge,” Dr. John says. “The extra rim in this block prevents the graft from adhering to the Weck-Cel sponge.”

To inject the graft into the recipient, surgeons say the most popular instrument is a modified intraocular lens injector, such as the Viscoject 2.2-mm injector (Bausch + Lomb) used by Dr. McKee. Dr. Jun says if you use an IOL injector, it’s important that it’s a closed-fluid system. “If you use one without a closed-fluid system, there will be cases where you’ll just run out of fluid,” says Dr. Jun. “It will leak around the graft and it won’t produce the size of fluid wave you need to get the graft tissue into the eye. If your system has a piece of tubing that’s attached to some sort of pipette that’s attached to a syringe, then it’s a closed-fluid system. But if you have an IOL injector with a big space where the IOL is supposed to slide in, and you then put viscoelastic in and you have a plunger—and the system isn’t closed to fluid—it can lead to difficult situations. For instance, you may encounter an instance where you have positive pressure where you need a little more fluid to get the graft in the eye but you’ll basically run out of fluid. Also, a closed-fluid system allows you to aspirate the graft into the injector without the graft physically resting on the injector material. If it’s continually surrounded by fluid it will float, and not make contact with the hard surface of the inserter device.”

Dr. McKee says it’s at this point, the injection, that you have to watch out for another difference between DSEK and DMEK: “You want to keep the eye very soft,” he says. “If there’s pressure in the eye as you inject the graft, it can eject from the eye. With DMEK, this will happen whenever there’s a pressure differential. When we use the closed-system injector, we always burp one of the paracenteses until there’s no difference in pressure between inside the anterior chamber and outside the eye so when we remove the injector the graft doesn’t come shooting out after it. Again, this is because the graft will follow fluid as if it were fluid.

|

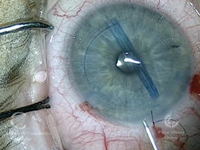

• Chamber depth. Surgeons say this aspect of DMEK is often the one that is most difficult for DSEK surgeons to acclimate to, since it runs counter to the protocol of almost all other intraocular surgeries: In DMEK, the chamber has to be fairly shallow.

“When you put a DSEK graft into the eye, you typically deepen the chamber and the graft unfolds itself because it wants to unfold and go back to its lenticular shape,” says Dr. McKee. “It doesn’t like to be folded up as it goes through the EndoSerter or Busin glide. Unfolding the DSEK graft is one of the easiest things to do. The opposite is true for DMEK. If you deepen the chamber with DMEK, the DMEK graft turns into the scroll that it wants to be. However, of course the whole point is to unscroll it into the proper orientation and get it adhered to the back of the cornea. That’s one of the biggest differences: The key is to shallow the chamber so when you do unscroll the DMEK graft the iris can act as your third hand and hold the graft open. This is a foreign concept to the DSEK surgeon.”

• Graft orientation. Because the graft will be rolled up and is so flimsy compared to a DSEK graft, it can be a challenge to determine whether it’s right-side-up. One strategy that Dr. McKee uses is a handheld slit lamp from Eidelon. “It looks like a small Maglite flashlight, with a small cylinder in the front that makes a slit beam,” he explains. “We put it in the finger of a glove so it stays sterile during surgery. We can then hold this slit beam and maneuver it at any distance or any angle to the eye. When you do that, you’ll first see a slit beam going through the anterior chamber, then the little wedge of cornea and then your graft. The graft always scrolls endothelium side out, so when you put the beam in there and see two little scrolls coming up at you, that means that if you unroll it in that orientation the endothelium will face iris as it should. On the other hand, if you see one broad scroll and the little scrolls going away from you, that means it’s upside down.”

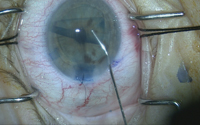

• Graft manipulation. As surgeons alluded to earlier, the DMEK graft is so delicate that once it’s in the eye, it can only be manipulated with liquid and air. Surgeons say this is one of the aspects of the surgery where the intuition you’ve developed in DSEK and other intraocular surgeries can mislead you. “The main difference in mindset between DSEK and DMEK is to realize that DSEK is a hands-on procedure and DMEK is hands-off, so to speak,” explains Dr. John. “It’s a no-touch technique. The donor tissue in DSEK has a stiffness that allows you to attach it with forceps, move it around, et cetera. Whereas with DMEK, the tissue is so thin that if you directly handle it, you can easily tear it. What that means is that even if you’re in the comfort zone with DSEK, when you transition to DMEK, it’s back to the drawing board. You have to depend a lot on fluidics to make the tissue do what you want it to do in the recipient’s anterior chamber.”

Dr. McKee says that to get good at using fluid as an instrument in the eye using a 27-ga. angled cannula, you have to be ready to embrace the counterintuitive. “You have to think about how fluid flows and understand that, whatever you do, the graft will do exactly what you told it to do, even if you don’t understand what you did,” he says. “Its response is based on fluid dynamics in a closed system. You have to understand eddy flows and how the graft will follow a current of fluid. People will watch me perform DMEK and say, ‘What you just did was counterintuitive to what the graft did—but somehow you seemed to know where the graft was going to go.’ I tell them that even though you don’t see the fluid, it’s constantly swirling around inside the chamber. That’s why even though I shot the fluid jet in the opposite direction of the graft, the graft responded and went where I wanted it to go. I was literally bouncing the fluid off the back of the cornea to make the graft do what I wanted.”

The surgeons have several tactics for using fluid to manipulate the graft. “When you inject fluid, you have to keep two factors in mind,” says Dr. John. “One is the direction of the injection; in other words whether it’s going in a radial fashion toward the center of the chamber or in a tangential fashion toward the periphery. The second factor is how forcefully you inject it.

“When you put the Descemet’s membrane graft in the anterior chamber, it’s rolled like a carpet that’s been rolled up on a floor, with the outer surface being the endothelium,” Dr. John continues. “So, when you inject fluid diagonally, you can turn this DM scroll on its long axis and, depending on the force of your injection, cause it to partially unroll. If you want the rolled membrane to move more centrally, then you can direct the fluid tangentially, setting up a circular current in the anterior chamber which will rotate the membrane on its vertical axis and, in doing so, partially unroll it.”

| |||||||||

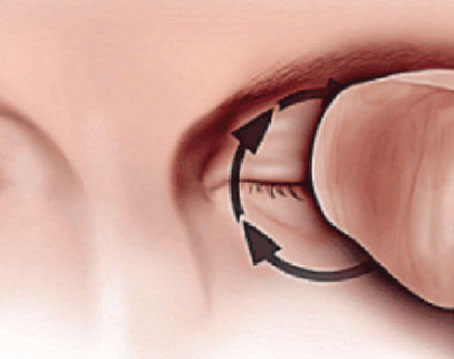

The act of tapping to maneuver the graft has an art to it too, says Dr. Jun. “You can tap on the corneal surface with a cannula to create fluid waves that move the graft into position,” Dr. Jun explains. “If you tap on the corneal surface within the margin of the graft, you can get it to unfold. Alternately, if you tap beyond the edge of the graft, you can get it to shimmy across the iris in a certain direction. Again, this comes down to the proper chamber depth. If the chamber is the right depth—relatively shallow—as you do these maneuvers you’ll see the response you want to see.”

Dr. John says the initial small air bubble may not be necessary. “The problem with using the small air bubble to unroll the Descemet’s membrane is you sometimes have difficulty getting the right-sized bubble,” he says. “And, when you tap on the air bubble, it can go outside the graft and into the wrong position, making the procedure more difficult.” As an alternative, Dr. John uses a smoother he designed as part of the DMEK set. “It’s a curved instrument with a ball at its distal end,” he says. “You can touch the corneal surface with the smoother and unroll the membrane and then move it to any desired position in a fairly consistent manner using gentle pressure on the outer corneal surface.”

Since a nearly full air bubble is required at the end of the case, however, surgeons note it’s important to perform an inferior peripheral iridotomy either a couple of weeks preop or intraoperatively.

• No vent necessary. Corneal venting incisions, which many surgeons use in DSEK to evacuate interface fluid, are actually counterproductive in DMEK. “You can’t use a venting incision in DMEK,” says Dr. McKee, “because when you put your diamond blade through the corneal stroma to vent you’ll go right through the DMEK graft.”

Build Your Knowledge

For surgeons looking to get serious about DMEK, there are resources from national societies, the Internet and individual corneal surgeons.

“All the traditional places for education are excellent,” Dr. Jun avers. “The AAO and ASCRS offer skills transfer courses, and surgeons such as Mark Terry, Francis Price and Gerrit Melles all welcome people to come and learn from them. We also provide learning opportunities here [at Johns Hopkins]. It’s best to take an actual course first, then follow that up with online resources such as case videos. Stay in close communication with people who have experience, both before and after you begin your own cases.”

Dr. McKee says there’s no substitute for experience. “DMEK is tough to do, but you have to stick with it,” he says. “I can picture someone coming in, taking our course, then going home and trying to apply what he’d learned and getting frustrated. To avoid that, he has to be in the wet lab practicing a lot. He has to have enough patients to do this on a regular basis, just like phaco. If you don’t do enough phaco you won’t get good at it. Residents have to do a minimum of 86 phaco cases to graduate, and even if they do 100 they’re still just good enough to get by. It takes practice and experience to do DMEK properly, but as your experience level grows, your operative time will decrease, and it will all have been worth it.” REVIEW