It’s best to approach pterygium surgery with the goal of reducing the chances of recurrence at all costs. While most pterygia are asymptomatic and regarded as garden variety lesions, they become serious problems if they recur after removal. These cases most certainly warrant a subspecialist evaluation. In this article, I’ll discuss some surgical approaches to pterygium, with particular emphasis on recurrent pterygium.

At the Outset

When a patient presents with a pterygium, the first thing to decide is whether it’s necessary to do anything at all. Many patients have only mild complaints related to dryness or irritation, and are often best observed or managed medically. Lubrication or topical NSAIDs may help relieve ocular inflammation and reduce the pterygium’s appearance. Protecting the face and eyes from excessive UV exposure may also help, as pterygium is more prevalent in regions that receive strong ultraviolet radiation.

Only a small percentage of pterygium cases warrants surgical excision. Indications for surgery include obstruction of the visual axis, pterygium-induced irregular astigmatism, chronic eye irritation and cosmetic dissatisfaction.

If you do decide to surgically remove the pterygium, your next decision will be to determine how extensive a procedure is required. One day postoperatively, no matter which method you used to remove the pterygium, it’s going to be gone. The question is: Is it going to come back? You want to do everything you can to make sure the answer is “no.”

Surgical Strategy

There are many different ways to do a basic pterygium removal, and potentially hundreds of modifications of the surgical technique. The most common method of simple excision takes about five minutes but is associated with a much higher relative risk of the pterygium recurring. For this technique, you simply pry the scar tissue off the cornea and snip it off. It’s effective for about 90 percent of cases, but that means you can expect approximately 10 percent of cases to recur (often with a vengeance).

As a medical adjuvant to the simple snip excision, one might also consider the adjunctive use of antimetabolites such as mitomycin-C on the surgical site. This isn’t something that I usually do however, because mitomycin carries the risk of scleral melting. If you’re concerned enough to pour chemotherapy on the surface of the eye to prevent the pterygium from coming back, then, rather than using the mitomycin technique, the optimal thing to do would be to try the PERFECT technique (explained in detail below).

Pterygium Excision

We often use a nerve blocker for pterygium excision. Retrobulbar anesthesia is typically most comfortable for the patient because it provides good levels of pain control during the procedure. Take care not to damage the underlying corneal tissue or remove stroma when prying the pterygium off the surface of the eye.

First, make an incision at the limbus where the pterygium begins to encroach over the cornea. Cut it free and peel it from the corneal surface using blunt dissection. Once the pterygium’s been removed, we often polish the cornea with a diamond burr. When the cornea has been repaired, we turn our attention to the sclera and conjunctiva.

Dissect the conjunctiva free from Tenon’s capsule. Remove all of Tenon’s capsule where the pterygium was.

Once you remove the scar tissue from the nasal aspect of the cornea and globe, you must then decide what to put in the gap where the scar tissue used to be. You have a few options:

Option 1: Do nothing. You can just leave it bare and it’ll re-epithelialize on its own. This has the highest risk of recurrence and induces the most patient discomfort, but it can be done.

Option 2: Cover the area with a biological material. Amniotic membrane, which can be placed and glued or sutured over the area of the defect, is a very effective method. We prefer to use glue, since it’s fast and simple. Amniotic membrane makes patients more comfortable and contributes to the healing of the tissue. However, it’s not quite as effective in discouraging recurrence as the third option.

Option 3: Rotational conjunctival autograft. This method might not be necessary in every case, but it’s the least likely to lead to recurrence. It’s also the technique I perform most often.

|

To perform a rotational conjunctival autograft, first measure the conjunctival epithelial defect and how much bare sclera you need to cover. Then, harvest the conjunctiva approximately 90 degrees or 3 to 4 clock hours away from the resected site, usually in the superior globe, with Wescott scissors. Dissect the conjunctiva free from the underlying Tenon’s capsule to an extent that matches the surface area of the pterygium. Create a pedicle flap and rotate it down to cover the area. Glue or suture the flap to the bed with 8-0 vicryl. If using glue, aim for as little glue as possible. Postoperatively, prescribe topical antibiotic drops such as fluoroquinolone q.i.d. for a week, and a steroid drop such as prednisolone acetate q.i.d., tapered over one to three months.

In terms of graft stability, gluing and suturing will give you the most peace of mind. A third technique, autologous in situ blood coagulum, will also work if you don’t have access to glue and you do have an extra 10 minutes to hold pressure on the site. The patient’s natural bleeding in the area will coagulate and anchor the amniotic membrane; however, you can’t be as sure as with glue or suture that the tissue will still be adherent after a day or a week. Besides, glue and suture are expensive, but the most expensive thing of all is time in the operating room—holding tissue down with your fingers for 10 minutes is quite expensive.

Recurrence (discussed below) is the most serious postop complication of pterygium excision. Additionally, you have to be concerned about scarring. When you’re cutting on the eye you’re generating scar tissue, so you need to be careful that you don’t end up with a tangled, fibrous mess. This is entirely possible, especially with multiple surgeries.

Other complications you may encounter include scleral melt due to the use of mitomycin-C; fibrosis, especially around the extraocular muscle in that location; infection, which is rare; and ocular surface discomfort, which can last for weeks or even months. Typically, the steroids help ease discomfort, but we also encourage the use of lubricant drops. Keep these complications in mind when forming your surgical strategy.

Recurrence

Young people are generally at increased risk for recurrence, as are African Americans and Hispanics of all ages, who tend to have more inflammatory phenotypes. Additionally, patients with double pterygia (on both the nasal and temporal aspects of the cornea) and bilateral double pterygia are at extremely high risk for recurrence. In these patients, you need to take every possible precaution and be very careful if you do any surgery on them.

|

It’s critical that these patients be watched carefully for recurrence. If you notice the area you’ve resected is starting to grow back, usually at a millimeter-by-millimeter pace, begin aggressive topical steroids immediately, since you want to do everything in your power to avoid a second surgery. If the eye is red and inflamed, that’s the time for drops, not surgery.

However, if you lose the battle—whether you’re inattentive, or the patient comes back years later, or was referred elsewhere and upon their return to you, the pterygium is growing over the visual axis—then it’s time to consider reoperating.

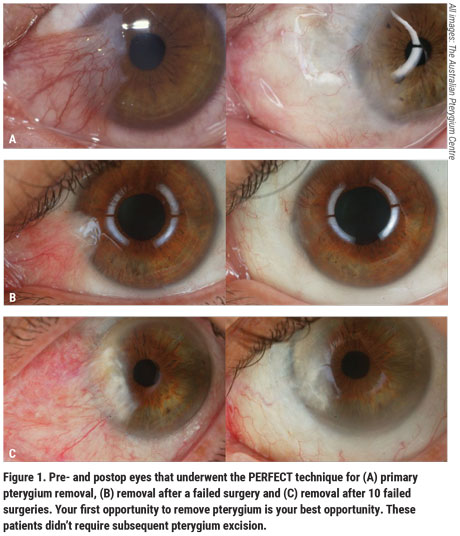

In the event that the pterygium recurs, I recommend trying the PERFECT technique. This technique, which stands for Pterygium Extended Removal Followed by Extended Conjunctival Transplant, was pioneered by Australian ophthalmologist Lawrence Hirst, MBBS, MD, MPH, who runs The Australian Pterygium Centre. It has by far the lowest risk of recurrence, at just 0.1 percent (Figure 1). This method involves extensive removal of Tenon’s capsule from the area of the pterygium and surrounding areas and is meant to be used on patients who have recurrent pterygium after previous surgical removal. This procedure has very good cosmetic outcomes, with most patients reporting being unable to tell which eye had surgery.

The PERFECT technique for pterygium consists of three components that each take about 15 to 20 minutes to perform. Following are the steps of the technique as described by Prof. Hirst in a video of the procedure.

|

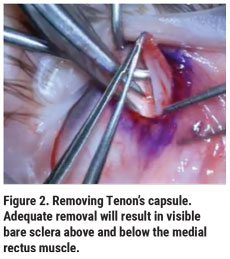

First, mark and transect the pterygium. Strip it from the corneal surface. Try to avoid having any residual pterygium tissue. Next, separate Tenon’s layer from the overlying conjunctiva and sclera, almost to the superior and inferior rectus muscles, and over the medial rectus muscle back to the caruncle (Figure 2). Adequate removal will result in visible bare sclera above and below the medial rectus muscle.

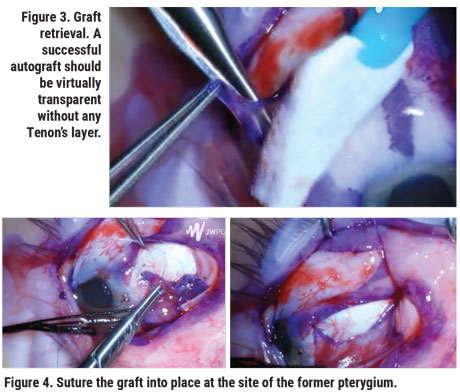

For the extended conjunctival transplant, mark the donor graft starting at the superior bulbar conjunctiva (Figure 3). The mark should extend almost to the superior fornix, and about 1 to 2 mm short of the limbus, and nasally, almost to the pterygium excision site. Leave a 5- to 7-mm bridge of conjunctiva and Tenon’s layer. At the donor site, the conjunctiva to be grafted should be separated from Tenon’s. A successful autograft should be virtually transparent, without any Tenon’s layer carried over with the graft. This helps to ensure that the donor site will heal with minimal-to-no scarring. The conjunctival graft is then transferred to the site of the former pterygium and sutured into place (Figure 4). To view a video of this technique, visit youtu.be/ODpQ_RbgHn4.

While it has the best success rate for preventing recurrence, by a wide margin, PERFECT is a long procedure—taking an hour to two hours of operating time, depending on your experience and skill level. However, I believe that anyone who’s had a pterygium recurrence needs to undergo this technique, as opposed to the standard “rip and clip.”

Ultimately, a pterygium isn’t something you want to keep hacking off over and over again. If it recurs early on, and you don’t feel comfortable doing the very refined PERFECT surgery yourself, it’s a good idea to refer the patient to a specialist. REVIEW

Dr. Parker is a cornea specialist in practice at Parker Cornea in Birmingham. He has no relevant financial disclosures.