Clear, fully accommodative vision may be the holy grail that ophthalmologists dream of providing their cataract patients, but that goal remains elusive. In the meantime, multifocal intraocular lenses remain a popular option for allowing good vision at both near and distance—at least in select patients.

Unfortunately, to produce good outcomes, multifocal IOLs require not only careful patient selection but also very precise refractive outcomes—meaning almost no spherical or astigmatic error. Given the challenges involved in achieving that level of precision today, doctors implanting multifocal lenses often need to compensate for the limitations of the surgery by adjusting the cornea preop or postop. In the United States, where toric multifocals are still not available, that often includes managing astigmatism.

“No matter how good your biometry or nomogram is, you’ll need to touch-up an eye containing a multifocal implant about 15 percent of the time,” says Richard Mackool Sr., MD, PC, director of the Mackool Eye Institute and Laser Center and senior attending surgeon at the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary, who has been implanting multifocal IOLs for 18 years. “I’m talking about routine, normal eyes, not eyes with strange biometries or excessive astigmatism. Fifteen percent of the time you won’t be within the ±0.5 D that satisfies 90+ percent of people. That’s because effective lens position is variable from person to person. Furthermore, K-readings are variable between machines and examiners, and probably between morning and night. These are factors you can’t control for.”

Here, several experienced surgeons share their thoughts on issues relating to this, including managing preop (and possibly postop) astigmatism; the importance of setting patient expectations; deciding whether any postop change is actually necessary; how long to wait before performing an adjustment; choosing the most appropriate corneal surgery to use; deciding whether to touch-up the cornea or exchange the IOL; and special circumstances that arise when doing both eyes in a short period of time.

Managing Astigmatism

Most astigmatism is addressed preoperatively or during the primary surgery in these patients. “The need for corneal correction of astigmatism with multifocal lens implantation is not uncommon, especially in the United States where we don’t have toric multifocal IOLs yet,” notes R. Bruce Wallace III, MD, FACS, founder and medical director of Wallace Eye Surgery in Alexandria, La., and clinical professor at LSU School of Medicine and Tulane Medical School in New Orleans. Dr. Wallace says that multifocal implants have been a very important part of his practice since the 1980s; he favors the use of limbal relaxing incisions to manage astigmatism in this situation. “LRIs have been a mainstay of my practice for over a decade, and I’m very impressed with how well they work,” he says. “The results aren’t perfect, but they can get a patient to a situation where he’s comfortable with his outcome. I think LRIs will remain an important part of our practice, even after toric multifocals become available. They are a less-expensive option, especially for low levels of astigmatism.”

|

Dr. Wallace has also switched to making his limbal relaxing incisions using this technology. “Now that we have a femtosecond cataract laser, we can make them more precisely,” he says. “It’s also the only reason we can charge a patient for the use of the laser, at present.”

Of course, astigmatism can also be an issue postop, though this is less frequent. When it does arise, it raises additional questions. “If the patient has no spherical refractive issues but astigmatism is a concern, how you proceed may be a matter of doctor preference,” says James P. Gills, MD, founder and director of St. Luke’s Cataract & Laser Institute and clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of South Florida. (His practice currently implants the Tecnis multifocal, and he frequently addresses issues in unhappy multifocal patients referred from other practices.) “In certain cases we use LRIs for small amounts of astigmatism; in other cases we use LASIK.

“However, if a significant amount of LASIK is required to correct astigmatism over a multifocal lens, some patients end up with a lot of glare, which upsets them,” he notes. “I’ve seen several of these patients, and it can be difficult to make them happy. This is especially true if you’re trying to correct hyperopic astigmatism. One reasonable alternative in the latter situation would be to consider a lens exchange, switching to a lens with more power, because myopic astigmatism is easier to address and might be managed with a relaxing incision.”

Dr. Mackool Sr., adds that some eyes simply are not good candidates for LRIs. “If you’re correcting pure astigmatism, meaning the spherical equivalent is close to zero, then you may want to address it with LRIs—unless you did LRIs before surgery either by blade or laser and the astigmatism remained,” he says. “In those cases, we find that you’re knocking your head against the wall. That cornea wants to heal in the same shape as it was before you made the incisions. So just bite the bullet and go to laser correction for those eyes.”

Setting Patient Expectations

Whenever patients pay out-of-pocket for a procedure, making sure their expectations are realistic becomes especially important. In the case of implanting a multifocal, that includes conveying the very real possibility that they will be among the 10 to 15 percent who end up needing a postop touch-up. “These patients have high expectation levels,” Dr. Wallace points out. “They may have friends who’ve had this procedure and are doing very well. Mainly, we want them to know that everything will not necessarily be perfect down the line, but we’re able to deal with that possibility. Explaining that to the patient ahead of time really helps.”

Dr. Mackool Sr. notes that it’s important to put this in writing. “Even if you do that,” he says, “80 or 90 percent of the patients who end up not seeing well because of a refractive error will come in and say, ‘I’m so disappointed.’ It doesn’t matter that you wrote it down. It’s human nature to hear what we want to hear and believe what we want to believe. So, you pull out the piece of paper and nicely explain that you did indeed warn them of this possibility.

“In fact, we give our patients dozens of pages of information to read,” he adds. “Not everything in there is immediately relevant to them, but much of it is. We find that patients who know more are more relaxed and confident as they go through this process—and the process can be difficult with a multifocal patient.”

“The other advantage of written materials is that they’re optional for the patients,” adds Dr. Mackool Jr. “Some patients who are very laid back may not read the materials. But many patients are very interested in being educated, and if you don’t give them accurate information, they’ll go to the Internet and come back with all kinds of questions from some website about the procedure you’re going to perform. Providing accurate information is far preferable.”

|

Of course, no matter what the surgeon does to warn patients ahead of time, some disappointment may be inevitable. “After they’ve had the surgery, if the outcome isn’t ideal, we once again emphasize that we have a solution to the problem,” Dr. Wallace says. “Yes, it may take a while to get there, but we have a solution. That makes them feel a lot better. Of course, in some cases helping them might mean something as simple as a YAG laser treatment.”

Is Further Action Necessary?

Once the initial surgery is complete, if something is not ideal, the surgeon has to decide whether further surgery is necessary (or will be beneficial). “You have to make sure these patients have perfect distance vision, or they will not be happy,” says Dr. Gills. “We’ll do a LASIK to correct as little as 0.75 D of residual refractive error in some cases. If you didn’t have a multifocal lens, you wouldn’t correct most of these patients. But when you have a multifocal lens, a small amount of spherical refractive error can cause problems.”

Of course, a central concern is knowing when to make the judgment call, since the healing process may cause the patient’s vision to shift for some time after surgery. “We usually wait about six weeks if we’re going to follow-up with LASIK,” says Dr. Gills. “A big factor in the final lens power is where the lens sits in the capsular bag. If the capsule shrinks, the anterior capsule may push the lens back, causing a small hyperopic shift. If the reverse occurs, you may get a myopic shift. So we wait at least six weeks to see what happens. We’d prefer to wait a year and a half, but the patients don’t want to do that.

“If the postop problem was simply a little astigmatism,” he adds, “we’d wait as long as possible and might ultimately decide to just do a relaxing incision.”

“We base how long we wait on stability, always,” says Dr. Mackool Sr. “Every refractive procedure should be based on that, whether it’s a touch-up after a multifocal implantation, LASIK on an eye that’s worn hard contact lenses for years, or an eye with astigmatic keratotomies whose effect is slowly disappearing. The more stable the eye, the more predictable the result. Some surgeons simply wait for three months, but if I had somebody whose refractive error at three months was different from their refractive error at two months, I’d have them come back at four months to see if it changed again.”

Dr. Mackool adds that the smaller the residual refractive error, the longer you should wait to do a touch-up. “When the error is small, small changes can occur that shift the patient from an unhappy camper to a happy camper, or vice versa, during that first six to 12 months,” he explains. “When we’re dealing with patients who are really on the fence, we explain to them that they are moving targets and we have to wait until they are as stable as possible. Patients are usually willing to accept that.”

Dr. Wallace notes that, besides giving the postop refraction time to stabilize, waiting before doing refinements also gives the patient time to adapt to the new visual system created by the multifocal lens. “Not only do patients not complain as much after two or three months, they actually see better,” he points out. “They notice fewer halos, and their midrange vision gets better. So, patients are less likely to be asking for a lens exchange at that point.”

|

Ultimately, he adds, your decision about whether to proceed with a touch-up should depend on the patient’s subjective opinion. “In most cases, if a multifocal patient has 0.75 or 1 D of astigmatism, you’ll have to correct that in order for the patient to be happy with his vision,” he says. “But if the patient is happy despite 0.5 or 0.75 D of astigmatism, trying to make the patient happier by correcting that astigmatism could backfire.”

Don’t Be Fooled by PCO

Another important issue when deciding whether or not a touch-up is warranted is to avoid being fooled by problems that can affect vision but won’t be resolved by a touch-up or lens exchange—in particular, posterior capsular opacity.

“It’s critically important that you determine the cause of the patient’s problem before attempting a touch-up,” says Dr. Mackool Jr. “For example, if the patient comes in after doing pretty well and says, ‘My vision isn’t as good as I thought it was,’ and you see a little refractive error, be sure there’s not a little bit of PCO. I don’t mean the kind of PCO that’s obvious; many times a small amount of PCO will have a large effect on a patient with a multifocal implant.

“I’ve had several patients with nondescript complaints,” he continues. “They’re not complaining about glare or halo, anything that’s problematic from a lens standpoint; just a vision issue. Doing a posterior capsulotomy has solved their problem. So before you go to corneal laser treatment, it’s a good idea to make sure there is no PCO. If there is, laser that first. You should definitely have a lower threshold for doing a YAG on one of these patients.”

The senior Dr. Mackool agrees. “The key in this situation is that they used to be happy, but now they’re unhappy,” he says. “If you’ve got a patient who had glare from the get-go, and you try to talk yourself into seeing a little PCO, think twice: That may be a person who has multifocal-induced dysphotopsia. If you do the YAG, even though the patient was never happy from the start, you may come up against the rare need to exchange the IOL. Now you have an open capsule, which changes the whole scenario. The risk factors are still manageable, but there’s no denying that you’ve increased them.”

He adds that one way to eliminate the likelihood of being fooled is to check the posterior capsule shortly after surgery and get the patient to tell you how he’s doing at night. “If you don’t pin the patient down, sometimes they’ll come in a year or two later with some complaints, and they won’t be able to tell you when the problem started,” he says. “You might have been able to pin them down if you talked to them shortly after the procedure, but a year or two later either their memory is not so good, or they never paid attention because no one was asking them to. Then you have some trickier decisions to make.”

Which Corneal Surgery?

Many surgeons today would automatically choose LASIK if a corneal touch-up was felt to be necessary, but arguments can be made for using PRK or even radial keratotomy instead. Dr. Wallace prefers to use LASIK. “Some surgeons prefer PRK in this situation, but in our hands, LASIK provides faster healing and less discomfort,” he says. However, he notes that dry eye can change that. “We had a patient this week who would have benefited from LASIK, but has such a severe dry-eye history—he’s been on Restasis and has had punctal plugs—that we’ve opted for doing an LRI initially for the astigmatism. After the cataract surgery we’ll determine what the spherical refractive error is, and then maybe do a two- or four-incision radial keratotomy.”

Both Drs. Mackool favor using PRK for touch-ups instead of LASIK. “Initially we did LASIK on top of multifocals, but we found that we’d lose a line or two of BCVA,” says Dr. Mackool Sr. “It’s true that the patient’s visual acuity would usually recover over a period of six to 12 months, because the cornea remodels its epithelium to reduce higher-order aberrations over time—at least if the higher-order aberrations aren’t too bad. But why put the patient through that if you don’t have to?

“Most patients in this situation only need a very small correction—a diopter or less of sphere and/or cylinder,” he continues. “So, they’re really ideal candidates for small PRKs. When you start doing LASIK in this situation—and I don’t care whether you make the flap with a femtosecond laser or a microkeratome—asking the cornea to heal absolutely perfectly is asking a lot. And increasing higher-order aberrations in this situation is a recipe for the patient to say, ‘I really don’t like my overall quality of vision.’

“So, our current recommendation is to do small-treatment PRKs,” he says. “We find that we don’t lose BCVA even transiently using that protocol. Yes, it takes the patient longer to get to his best vision, maybe a month. And some of them, maybe 25 percent, will have some discomfort for a day or two, maybe even pain, but that’s controllable with meds.”

He adds that in this situation he uses mitomycin-C. “We use mitomycin for a minimum of 60 seconds, regardless of the extent of the treatment,” he explains. “There have been reports in the literature of successfully doing this with 10 or 20 seconds of mitomycin, but we had some instances of haze with small treatments. That’s pretty frustrating.”

“We see virtually no haze [with our current protocol],” adds Dr. Mackool Jr. “It’s much safer, and there’s really no downside to it.”

Of course, some surgeons would hesitate to use PRK for fear that patients would complain about the discomfort. However, Dr. Mackool Jr. notes that patients don’t complain as long as they’re fully educated before the surgery. “When patients are prepared for what you’re going to do, they tolerate it extremely well,” he says. “They expect to have the bandage contact lens in for a week, and they understand that their vision will improve over time. We don’t get any complaints in those circumstances. It’s only when patients don’t know what to expect that these things become an issue.”

Touch-up or Exchange?

Occasionally a patient will have a more serious refractive surprise after multifocal IOL implantation. In that case, the surgeon has to decide whether a lens exchange would be a better option than a corneal refractive procedure.

Dr. Wallace says that, faced with a need for postoperative adjustment, he prefers to avoid exchanging the implant. “There are two reasons for that,” he notes. First, it’s more surgery and work inside the eye. Second, we want to wait to make sure that the refraction is stable before we do anything to change it; it might improve on its own. So, we like to wait at least three months before we make any sort of refractive change on an eye that had a refractive surprise following a multifocal implant. That, in turn, adds to the impetus to avoid exchange, because after three months it’s riskier to exchange an IOL, compared to, say, three weeks postop.

“Basically,” he continues, “we wouldn’t exchange a lens because of a refractive error unless it was something that we couldn’t correct on the cornea. If the patient has significant dry eye or is hyperopic, that might require a lens exchange, but that’s not common at all in our practice.”

Dr. Gills says the extent of the refractive surprise is a key factor in his decision. “If a refractive surprise was 1.5 D, a lens exchange would be my first choice, but we could certainly do LASIK as well,” says Dr. Gills. “If the surprise was greater than 1.5 D, I’d prefer to go with a lens exchange. I like to see as little corneal change as possible.”

|

“If you start doing laser correction of even moderate errors, you’re going to be creating more higher-order aberrations on the cornea,” adds Dr. Mackool Sr. “If you add those on top of a multifocal, the patient’s vision will suffer.”

Occasionally, other circumstances will make a lens exchange impractical. “Suppose I put in a capsular tension ring to address zonular laxity during the primary procedure,” says Dr. Mackool

Sr. “I’ve done this many times with good results. But once in a while this type of eye may toss a refractive error problem at you because it has an unpredictable effective lens position. In that case, I’d be gun-shy about going in to do an exchange. I’d be far more likely to fall back on laser correction.”

Creating a Safety Net

Not surprisingly, many surgeons prefer to avoid lens exchange because of the difficulty of the procedure. However, Dr. Mackool Sr. notes that he and his colleagues have developed a surgical technique that can be used during the primary surgery that makes a lens exchange far less difficult, should it need to be done.

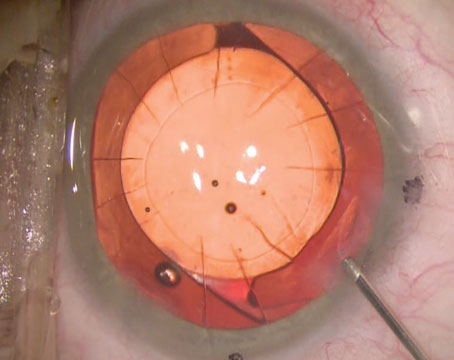

“We reported on this technique about five years ago,” he says. “When we put in multifocals, we remove the epithelium from beneath the anterior capsule. Those cells release certain chemical agents such as fibronectin that cause the anterior capsule to adhere to the optic of the lens, typically three to four weeks postop. Removing those cells delays adhesion of the anterior capsule to the haptic for six months to a year. If you have to exchange the lens because of a glare problem six months postop, in most cases you’ll find that the optic has not adhered to the capsule. So we do this routinely for all multifocal patients.”

|

“Some people might argue that adhesion is good for toric lenses,” notes Dr. Mackool Jr., “but if they’re going to shift, they usually shift so early postop that better adhesion wouldn’t make any difference.”

Dr. Mackool Sr. agrees. “It’s usually the myopic eyes with large bags that have rotation of a toric lens,” he points out. “Some surgeons remove the epithelial cells from the anterior capsule on every cataract patient, and they haven’t reported any increase in toric rotation. There was a report from Japan that removing the epithelium from the anterior capsule resulted in earlier PCO, but we haven’t seen that.

“In the meantime, the fact that the lens doesn’t adhere to the capsule so quickly removes the urgency of managing a possible lens exchange,” he concludes. “If a patient comes in complaining of glare in the first eye, I tell him we should wait and see what happens before we proceed. I know I can exchange the lens at six months, if necessary. The risk won’t be any greater at that point in time. Of course, the majority of these patients don’t end up getting an exchange. They come to grips with the glare issue.”

When Doing Both Eyes

Often a surgeon will do both eyes in sequence, raising a few special considerations. First of all, Dr. Mackool Jr., notes that in this situation it’s important to operate on the nondominant eye first. “A patient can potentially tolerate a little bit of glare and halo in the nondominant eye and still get the benefits of reading vision,” he points out. “So you haven’t lost much if you put a multifocal lens in one eye but have to change your plan and put a standard aspheric implant in the other eye.”

Also, it’s important for the patient to provide key information about the outcome in the first eye, as this will potentially impact how you treat the second eye. Not surprisingly, patients may not provide that information unless you specifically ask them to. “We wait two weeks before doing the second eye,” notes Dr. Mackool Jr. “We tell every patient, ‘Don’t worry about your vision during the first week. But during the second week, before you have the other eye done, pay attention to how much glare you have; test the eye at night.’ If they’re going to have trouble, you want to find out about it before you do the other eye. When patients are referred in from other practices, we often find that the surgeon put in one lens and then automatically put the other one in without really checking to say whether the patient had any complaints. At least one in 20 patients will have glare or halo that’s bothersome, and you don’t want to proceed with the second eye if that’s the case.”

|

Multifocal Touch-up Pearls

• Don’t exceed the astigmatism you can treat. “If the patient has more than 2.5 to 3 D of astigmatism, we would discourage multifocals altogether,” says Dr. Wallace. “There is only so much astigmatism you can correct with LRIs or LASIK. Of course, those limits are likely to change when toric multifocals become available.”

• Include potential touch-ups in the up-front cost. “People like to pay for a complete job, and you need to deliver it,” notes Dr. Mackool Sr. “Making sure the cost is covered is important if you want your practice to run as smoothly as possible.”

• Make LRIs a little more peripheral for a multifocal patient. “LRIs are really corneal relaxing incisions, and you don’t want to interfere with a LASIK flap, should LASIK become necessary,” says Dr. Wallace. “For that reason we’re typically a little more peripheral when it comes to doing limbal relaxing incisions for patients that are receiving multifocals.”

• See the patient monthly during the initial postop period. “During the three-month period when we’re waiting to see whether a postop treatment will be necessary, we have the patient come in every month,” says Dr. Wallace. “This accomplishes several things. First, when a patient has vision trouble after surgery, it’s possible that the patient is bothered as much by tear dysfunction in that eye as by any refractive-error issues. Seeing him every month allows us to monitor the patient’s tear function and do whatever we can to support it.

“Having him come in also allows us to look for a trend in the postop refraction,” he continues. “And, it shows the patient that we care. That’s important because these patients are typically not really happy. They paid out of pocket for a better result than they’re having. Seeing them every month shows them that we’re staying on top of their situation and doing what we can to make it better.”

• Don’t proceed with a touch-up unless any dry eye has been addressed. “This can be a huge issue,” notes Dr. Mackool Sr. “Some patients who didn’t have dry eye preop develop it postop as a result of using multiple drops. Don’t hesitate to put these patients on a lubricant or punctal plugs, or both. Dry eye can produce almost any kind of refractive error—cylinder, myopia, hyperopia, variability. So get rid of the dry eye before proceeding.”

• Remember that reading problems are often related to pupil size. “At least once a month I see a patient with a ReSTOR implant and good distance vision but difficulty reading,” says Dr. Mackool Jr. “The surgeon who implanted the lens is perplexed and the patient is too. It turns out that all the patient needed was a smaller pupil to read. The functionality of the lens for reading improves if the pupil is less than 3.5 mm in size. If they use a dilute pilocarpine solution when reading, their problems go away. It also eliminates a lot of distress if you warn patients in advance about this possibility.”

Dr. Mackool Sr. notes that this problem isn’t limited to the ReSTOR lens. “I’ve seen the same problem with other diffractive multifocals,” he says. “It turns out that a certain accommodative pupil diameter is optimal. If you don’t have that, you’ll tend not to do as well with the various lenses for near vision. It’s just the way it is. Of course, it would help if surgeons measured pupil diameter when deciding whether a patient is a good multifocal candidate, but I’m not sure that surgeons always do this.”

• Only use a piggyback lens as a last resort. “The piggyback on multifocal question is controversial because we don’t have a lot of data,” notes Dr. Mackool Sr. “No one has done a huge series of those. But suppose I had a patient who couldn’t have laser vision correction because of dry eye or keratoconus. Suppose he has a multifocal in there and a refractive error and he’s miserable, and suppose I don’t want to exchange the lens because I think the zonule might be lax.

“Would I do a piggyback lens in that situation?” he continues. “Yes, I would. I’ve seen a few done. But I’d tell the patient in advance that we don’t have a lot of data on it, and he might not like the quality of vision it produces—although I suspect in most patients it wouldn’t harm their quality of vision. Also, it’s relatively easy to remove a piggyback lens, although then you’re back to square one. Fortunately those situations are pretty rare.” REVIEW