Here, experienced surgeons offer their opinions on the advantages of the toric lenses currently available, and advice for getting optimum results when implanting them.

Surveying the Options

The first toric option approved in the United States, still in use, was the STAAR single-piece plate toric IOL. However, the AcrySof toric IOL has become many surgeons’ go-to toric lens in recent years; reported good outcomes and an increasing range of power options—as well as having been the only toric IOL with haptics for a number of years—have made it the leading option.

More recently, two new toric IOLs have become available: the Tecnis toric from Abbott Medical Optics and the Trulign toric from Bausch + Lomb, the latter created on the Crystalens platform.

Douglas D. Koch, professor of ophthalmology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, was involved in the clinical trials of the Tecnis toric and has worked with the Tecnis lens for about three years. “I like the Tecnis a lot,” he says. “There are many similarities between the AcrySof and Tecnis torics; they’re both on a single-piece, hydrophobic platform and they’re both terrific lenses. They differ in that the Tecnis is clear, not yellow, and it has a little more negative spherical aberration and less chromatic aberration.

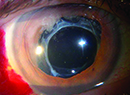

“The Tecnis comes in four powers that correct 1, 1.5, 2 and 2.75 D of astigmatism at the corneal plane,” he continues. “For now, the AcrySof has the advantage in terms of the wider range of available powers. The Tecnis material is hardy and doesn’t easily scratch. It also has a lower refractive index and lower reflectivity so that it’s not cosmetically noticeable when people look at someone who has the implant. The vast majority of patients don’t care about this, but every once in a while it comes up. On the other hand, the Alcon lens has a full 6-mm refractive optic. Overall, I like both lenses a lot.”

Dr. Koch notes one difference when implanting the Tecnis. “The lens is a little different going in because you can rotate it easily in either direction when you’re trying to position it,” he says. “Because it’s very flexible and the haptics are a little less sticky than the Alcon lens, you can actually back-rotate it, which is a nice feature. I wouldn’t try to back-rotate it 90 degrees, but you can go back 20 degrees or so if you need to.”

Terry Kim, MD, professor of ophthalmology at Duke University Eye Center in Durham, N.C., has been using the Trulign toric. “The Trulign will allow us to reduce cylinder in patients who are looking to get more range of vision with the Crystalens,” he notes. “I think that’s important, because whether you’re talking about a multifocal or accommodating lens, we all know that astigmatism can adversely affect outcomes. Until now, when we implanted these lenses we had to treat astigmatism with a limbal relaxing incision or astigmatic keratotomy, and these incisions just aren’t that accurate, especially when correcting more than 2 D of astigmatism. So having the ability to treat astigmatism built into a lens like the Crystalens is a welcome addition. It will reduce cylinder and improve results.”

Dr. Kim notes that the Trulign doesn’t seem to rotate much postoperatively. “One thing that I’ve found with this platform is that it does stay where you put it at the end of the case,” he says. “That’s one of the keys to success with any toric IOL; you don’t want intraoperative or postoperative rotation.

“With a single-piece Tecnis or AcrySof toric IOL, I advocate going behind the lens with the irrigation/aspiration tip to aspirate all of the viscoelastic out of the bag, because any residual viscoelastic between the lens and the capsule could allow potential lens rotation intraoperatively or postoperatively,” he continues. “With the Trulign that’s not as much of an issue because you can do the ‘rock and roll’ technique, where you tilt the lens to its side using the I/A tip to burp out the viscoelastic behind the lens.”

| ||||

“I haven’t used the STAAR one-piece lens lately, just because my results with the AcrySof toric have been so outstanding,” says Stephen S. Bylsma, MD, who practices at Shepard Eye Center in Santa Maria, Calif., and is a faculty member at UCLA Department of Ophthalmology, affiliated with Jules Stein Eye Institute. “The AcrySof is very stable in the eye and has a wide range of astigmatism-correcting powers. However, the STAAR plate format does have some advantages. Some torics can cause a ‘cat eye’ reflection that can be observed by someone else. I’ve had patients who have noticed it in others, and they specifically request that they not have that effect. In those cases I use the STAAR lens. Also, there are no glistenings in the STAAR lenses, because the lens material is different.”

Lenses vs. Incisions

Despite the weaknesses inherent in correcting astigmatism with manual incisions, the advent of femtosecond-laser-created corneal incisions has raised the possibility that these more precise incisions might make corrections on a par with toric IOLs.

Nevertheless, toric IOLs still have some significant advantages. “The issue for me has always been one of optically correcting astigmatism rather than using tissue manipulation,” says Dr. Bylsma. “Correcting astigmatism with an IOL is much more accurate. To not have to do LRIs along with the Crystalens, for example, is a big advance.”

“A toric IOL helps to save tissue and creates cleaner optics,” agrees Dr. Mamalis. “I generally only use LRIs now for very small amounts of astigmatism. If the patient has a greater degree of astigmatism than we’re able to correct optically, that patient would require an additional tissue procedure such as PRK, LASIK or an LRI, depending on the amount. In that situation we debulk the astigmatism with the strongest lens we have available; that helps to minimize the amount of tissue correction needed.”

| ||||

Dr. Kim acknowledges, however, that femtosecond lasers may eventually impact whether surgeons choose to implant a toric IOL. “As you know, femtosecond lasers can create LRI and AK incisions,” he says. “They can be very precisely programmed. For instance, when I do an LRI manually I use a 600-µm keratome blade to create a limbal relaxing incision in the peripheral cornea. Like most surgeons, I don’t measure the peripheral corneal thickness first, so I never really know if I’m getting down to exactly 90 percent deep, for example. But a femtosecond laser, which takes an OCT image of the cornea, can be programmed to make that incision down to exactly 90 percent depth.

“In addition,” he continues, “you can customize the design of the incision, in terms of length, depth and angulation and whether you want it to open all the way to the epithelial surface or not. Furthermore, many surgeons are not actually opening the incisions at the time of surgery; instead, they titrate the effect of the incision by opening it later, as needed, once the patient has stabilized after cataract surgery.

“What we don’t know is, how will the wound-healing response compare to that of blade-created LRI incisions?” he continues. “We don’t have enough data yet to know how that’s going to affect our treatment of astigmatism, and whether these will be better than manual incisions. But femtosecond lasers have definitely opened up another approach to treating corneal astigmatism, and it may eventually impact the manner in which surgeons choose to use torics IOLs.”

|

“In terms of LRIs made manually, they tend to undercorrect a little bit compared to toric lenses,” he adds. “And they don’t necessarily offer the patient a cost savings compared to implanting a toric IOL. It’s not just the cost of the lens itself that the patient is paying for; it’s the extra measurements and work that goes into evaluating the eye preop, as well. We still have to do that work if we’re planning to do a limbal relaxing incision. It’s true that some doctors don’t charge to do LRIs; they just do them automatically. If I’m doing a touch-up, then I won’t charge for an LRI. But if I’m doing it as a primary correction, then there is a charge involved.”

Making the Most of Torics

The following strategies can help maximize your success with torics, whether you’re implanting the newer or older approved lenses.

• Offer the toric IOL option to all patients with astigmatism. “Insurance and Medicare do not cover these lenses, so patients have to pay for them out of pocket,” Dr. Mamalis points out. “Obviously, not all patients will have the resources to afford a toric lens. However, you don’t want to prejudge and assume someone can’t afford it.

“Whenever a patient has significant astigmatism, regardless of appearances, I let him know that we do have an implant available that can correct that, although he’ll have to cover the cost himself,” he continues. “If that’s not feasible, we can correct his astigmatism afterwards with eyeglasses, as he’s most likely already doing. Always give everyone the option and let them make the decision.”

• Take topography measurements before doing tonometry or putting in dilating drops. “If a patient comes in with a cataract, we do the topography prior to dilating or measuring IOP because both drops and tonometry can disturb the surface of the eye and make our topography measurements less accurate,” says Dr. Mamalis. “We do the topography measurements on a virgin cornea. If we realize that the topography was inadvertently not done first, we have the patient come back later for a second measurement. It’s really important to get the most accurate topography possible.”

• Don’t rely on a single measurement source. Dr. Mamalis says he relies on at least two instruments to make his preoperative astigmatic measurements. “The IOLMaster is pretty good at picking up the axis of astigmatism,” he notes. “But for the magnitude of the astigmatism, I find that corneal topographers give you more accuracy.”

Dr. Bylsma also says he uses a combination of topography and keratometry to determine his preoperative measurement. “We do automated keratometry at the screening,” he explains. “Then we use corneal topography to further analyze the shape of the cornea. We also have the keratometry that comes with the preoperative A-scan done by the IOLMaster or Lenstar, both of which are excellent tools. We look at all of those and make our judgment based on how much they agree.

“Generally they agree very well,” he adds. “But again, none of this takes into account any posterior corneal astigmatism, which can lead to a less-than-perfect correction despite careful preop measurements.”

• When the measured astigmatism is halfway between available lens powers, choose carefully. Dr. Bylsma says that in this situation he will generally choose the weaker power lens. “We don’t want to flip the astigmatism axis,” he says. “Patients are used to their own astigmatism; they’ve had it all their lives. As long as we reduce it significantly and leave it in the same axis, they’re very happy. But if we give them a new axis of astigmatism by overcorrecting their previous astigmatism, they can be very unhappy; they’re not used to the distortion being in the new direction.”

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• If a patient with very low ATR astigmatism has a correction for that in his spectacles, a toric lens is a good choice. “Even if the amount of ATR astigmatism you measure is small, say 0.4 D, if the patient has a correction for that in his glasses, that’s a pretty good indication that there’s some ATR power on the back surface of the cornea,” notes Dr. Koch. “If you don’t provide any correction for that seemingly small amount of astigmatism, that 0.4 could end up being 0.8 postoperatively, and the patient will be unhappy with his quality of vision. In those instances, I recommend a toric lens.”

• Have a printout of your axis-calculator results in the OR where you can see it during surgery. “All toric IOL companies have Web-based axis calculators that are user-friendly,” notes Dr. Kim. “I recommend making a printout of the result and having that printout taped to the wall or on your microscope. It’s very easy to accidentally align the lens in the wrong axis; having the printout visible helps ensure that you get the orientation right the first time.”

Dr. Mamalis agrees that this is a helpful strategy. “I line the printout up exactly as the eye is aligned through the microscope, just as a final check to make sure we’re putting the lens in the right place,” he says.

• When implanting a Trulign, insert the mouth of the inserter all the way into the anterior chamber. “The Trulign lens is on the Crystalens AO platform, so if you’ve been implanting the Crystalens AO, this procedure will be similar,” comments Dr. Kim. “If you’re not familiar with this platform, I advise enlarging your smaller incision to 3 mm in order to make room for the lens and the cartridge. Then, to insert either the Crystalens or the Trulign, I recommend using the Crystalsert Delivery System, and making sure that the mouth of the cartridge is all the way into the anterior chamber—as opposed to just using what’s called ‘wound-assisted delivery,’ where the mouth of the cartridge just sits in the incision itself.

|

“Another issue is that sometimes the trailing haptic will not fully go into the bag,” he adds. “If the mouth of the cartridge is all the way in, you can make sure that the haptics are at least in the anterior chamber. Then when you pull the cartridge out, you can position the trailing haptics with a Sinskey hook into the capsular bag.”

• Remember that the Trulign can be rotated in either direction. “When implanting the Trulign, I use what I call a push-and-pull technique, done with a Sinskey hook,” explains Dr. Kim. “Unlike the conventional single-piece acrylic toric IOL platforms, where you have to rotate the lens clockwise to get it to the axis that you want, you can rotate the Trulign clockwise or counterclockwise by pushing and pulling on the haptic-optic junction on the IOL until the lens reaches the desired axis. That’s because the haptic configuration is balanced; it’s symmetric on both sides.” (The Tecnis toric can also be back-rotated, although to a lesser degree, as noted earlier.)

• When a lens is misaligned, help is on the Web. “Occasionally, because of imperfect measurement, imperfect placement or postop lens rotation, the astigmatic axis of a toric IOL will need to be adjusted,” says Dr. Kim. “In that situation, you can get help at astigmatismfix.com, a free website created by Minneapolis surgeon David Hardten, MD, and Sioux Falls, S.D. surgeon John Berdahl, MD. If the spherical equivalent of your refractive result is close to plano, it allows you to enter parameters such as the manifest refraction, toric lens model and axis of position, and tells you what the correct optimal position of the toric IOL should be and what refraction the corrected axis will give you. It’s a very helpful tool to use if you need to realign a toric IOL.” (Dr. Berdahl confirms that the nomogram at astigmatismfix.com will work for the newer toric IOLs as well as the older toric options; all the lens options are available on the website.)

• Don’t forget about monovision. “If you don’t want to go with a lens like the Trulign that extends range of vision, you can still do monovision with a toric IOL and have very good results,” notes Dr. Kim. “I generally reserve this for patients who are wearing contact lenses with monovision who are already used to it, but the results can be excellent. I think we automatically tend to tell our toric IOL patients that we’re aiming for distance vision only, and they’ll still need reading glasses. But it’s worth remembering that monovision is also an effective option with these IOLs.”

Dr. Bylsma agrees. “Toric lenses are helpful in this situation,” he says, “because monovision only works well if each eye has excellent, clear vision at its respective distance.”

The Technology Keeps Coming

A big part of getting toric IOLs to live up to their full promise is getting them perfectly aligned inside the eye. New technologies in the offing should make that ever easier to do.

“Alcon has a reference unit/digital marker system called Verion,” notes Dr. Kim. “The reference unit portion will allow you to take an image of the patient’s scleral/conjunctival blood vessels and pupil/iris architecture and plan your astigmatism treatment on that, whether it’s going to be an LRI/AK incision or a toric IOL. It puts the information on a USB stick that you plug into a device that attaches to your OR microscope or your femtosecond laser; the digital marker portion then provides a digital overlay on the eye showing exactly where the orientation of your LRI/AK incision or toric IOL position should be.

“This is going to be a paradigm shift, in terms of not having to manually mark the patient preoperatively or intraoperatively to know where the toric IOL should align,” he adds. “I think it’s going to be a big improvement, simplifying and automating the process as well as eliminating the risk of transposition and transcription errors.”

In the meantime, Dr. Mamalis notes that there are plenty of new toric lenses that simply haven’t made it into the United States. “Around the world there are toric options too numerous to count,” he says. “Most are not approved in the United States. There are torics made of both hydrophobic and hydrophilic acrylic materials, and some that are made to go into the sulcus as a piggyback lens. We’ve tried those in our laboratory; they allow you to correct astigmatism without corneal or lenticular surgery. I think they’re a great option, but that’s a niche market, and the cost of getting approved by the FDA is very high. Also, in Europe, Rayner will custom-make an IOL for your patient. That could potentially save the surgeon from having to combine a toric IOL with arcuate incisions in the cornea or LASIK surgery on the cornea.”

With the technology advancing—and more toric IOL approvals inevitable—it seems clear that these lenses are likely to become an ever-larger part of the cataract surgeon’s armamentarium. “This is an excellent technology, and I think it will continue to be part of our armamentarium to treat astigmatism, even with the availability of femtosecond lasers to make corneal incisions,” says Dr. Mamalis. “I don’t think this is going to go away.”

Dr. Koch agrees. “In general, toric lenses are my favorite lenses,” he says. “To me, they eclipse multifocal IOLs as a valuable adjunct to my cataract practice.” REVIEW

1. Koch DD, Ali SF, Weikert MP, et al. Contribution of posterior corneal astigmatism to total corneal astigmatism. J Cataract Refract Surg 2012;38:12:2080-2087.