In my early high school years I was very interested in science and medicine. I thought I’d pursue a career in medicine, and I was able to get into Johns Hopkins. However, the premed experience wasn’t what I was expecting. I was put off by how competitive it was; the students were very grade-conscious and driven with-out seeming to appreciate what they were getting into. So within a year I switched my major to philosophy and then earned my degree. Along the way I started doing social work and helped run an inner city tutoring program for kids in Baltimore. When I graduated, I got a full-time position at the university running that program, which I did for a number of years.

Then, in my mid 20s, I was driving down the New Jersey turnpike when I noticed my vision getting blurry off and on. I went to see an eye doctor and found out that my eye pressure was in the low 30s. At the time, I knew nothing about glaucoma, but the doctor seemed rather alarmed. Knowing that I’d gone to Johns Hopkins as an undergrad, he offered to connect me with some of the people at Hopkins and Wilmer Eye Institute to get a second opinion and a higher level of care than he felt he could offer me.

Sure enough, my diagnosis was confirmed, and I started on drops and treatment. This experience sparked my curiosity about glaucoma, so I tried to learn as much as I could, at least partly as a way to head off my own fears about the disease. Eventually I asked about working in glaucoma research, and I became a lab tech in a glaucoma research group at Wilmer. Needless to say, over the course of the next three years I learned an enormous amount about glaucoma. Ultimately, that reignited my interest in going to medical school—but this time I was several years older and I had a pretty clear idea about what it was I wanted to learn and pursue. That made it much easier to do.

The Other Side of the Slit Lamp

Having been a glaucoma patient myself, I can tell you that the experience is difficult to appreciate if you haven’t been there. Today, when I work with glaucoma patients—especially at the outset of treatment—I am acutely aware of what they’re experiencing. It puts me in a unique position to address those fears that the patient may be afraid to express—fears that the physician may not be aware of.

Here, I’d like to share a few of the things I’ve learned as a result of being both a glaucoma doctor and patient.

• Be aware that a diagnosis of glaucoma can be a very frightening experience. Essentially, you’re being told that you could lose your sight, which is many people’s greatest fear. The initial diagnosis is very unsettling and can be profoundly life-changing. I’ve had patients cry upon hearing the news, and I totally understand that reaction. After I first found out that I had a potentially blinding disease, there were times when I was distraught. I remember asking “Why me?” and thinking how unfair this was.

The impact was even greater when I was first told I would need surgery. I remember the doctor saying that the best thing to do was a trabeculectomy. After this announcement, my ophthalmologist continued to talk for 20 minutes, explaining what this meant. For the life of me, I have no recollection of anything he said after he told me I needed surgery. I was in a state of shock. I remember walking out of the exam room into the hallway and seeing a large print of a Van Gogh painting. I looked at it in a way I had never looked at a painting before. The realization that my vision could be gone just really hit me. It was a very scary moment.

Because of these experiences, I’m very sensitive to how patients may be feeling when they learn they have glaucoma or find out they need surgery. A patient’s feelings are not always obvious, because for the most part patients keep it together. It’s rare to have a patient break down and reveal what he or she is feeling. But if you want to serve your patients well—not to mention making sure they hear what you’re saying to them—you need to realize the state your patient may be in after hearing the news.

Fears that glaucoma patients often have include:

— fear of going blind;

— fear of asking you questions;

— fear that vision loss will cost them their job;

— fear of not being able to pay for the drugs you prescribe;

— fear of pain during or after surgery;

— fear that a surgical procedure—or even an eye drop—will change the appearance of their eyes.

Fortunately, these fears decrease significantly over time as patients learn to live with their disease and experience successful treatment. The fear never goes away completely, but the initial shock does gradually dissipate.

| Lifetime Visual Prognosis for Patients with POAG or NTG | |||

| Time Point | Reason for poor vision | No. of POAG/LTG patients eligible for partial-sight or blind certification | |

| Partial Sight | Blind | ||

| At Presentation | Glaucoma damage alone | 1 (0.8 percent) | 0 |

| Glaucoma plus other pathology | 7 (5.8 percent) | 0 | |

| Total | 8 (6.6 percent) | 0 | |

| At final clinic visit | Glaucoma damage alone | 8 (6.6 percent) | 0 |

| Glaucoma plus other pathology | 9 (7.4 percent) | 4 (3.3 percent) | |

| Total | 17 (14 percent) | 4 (3.3 percent) | |

| A 2004 retrospective study of 121 case histories of Caucasians with primary open-angle glaucoma (n=113) or normal-tension glaucoma (n=8) found that the diagnosis did not lead to blindness for 96.7 percent of the patients. Those reaching blindness all had other ocular pathologies in addition to glaucoma. Only 14 percent qualified for partial sight certification at their final visit before death, and of those only 6.6 percent were due to glaucoma alone.1 | |||

• Make sure to clarify that glaucoma is unlikely to lead to blindness when treated appropriately. Given that patients are almost certain to feel some fear, one of the most important things you can do is reassure the patient during the first few visits, especially when the disease is first diagnosed. Make sure the patient understands that glaucoma is very treatable, something that can be controlled, and that very few patients go blind from it. (For example, see the table above.)

At the same time, you need to emphasize that this is conditional. The condition is that the patient takes his medications, follows your instructions and follows up with appointments. This could mean using drops and/or having surgical procedures periodically for the rest of the patient’s life, but if he’s willing to stay with the program, the disease is very likely to remain under control, preserving the vision that the patient currently has. That understanding should go a long way toward allaying the patient’s fears.

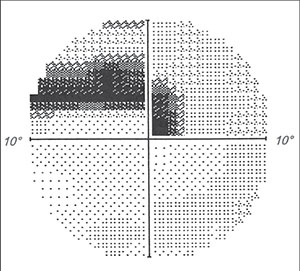

• Keep in mind that field loss may be invisible to the patient. One of the surprising things I’ve learned from having glaucoma is that you can lose a significant amount of visual field without being aware of it. I have significant field loss in both eyes, including a very large nasal step and arcuate scotoma in one eye. Remarkably, I never notice any defect in my vision in that eye at all. My other eye has a paracentral defect pretty close to fixation, and again, I’m oblivious to it unless I cover the other eye and deliberately search for it using an Amsler grid.

Ironically, medical books about glaucoma that describe visual field loss show big black spots on pictures, as if a patient looks out into the world and sees big black splotches. You don’t; your mind is unaware of what you’re not seeing. That’s why so many patients lose vision for years without noticing. (Needless to say, that’s one reason vision screening is so important.) For that reason, when you do find vision loss it’s important to go over the visual field results with the patient and explain what the printout is showing, as well as explain why she may not be aware of the problem. Compliance may depend on the patient understanding that she really is losing vision, despite not being aware of it.

• Know your patient’s background and level of under-standing. Getting patients to understand what we’re saying is a key to compliance. They have to understand the disease; believe that it’s treatable; and understand what our treatments are doing, so they’re motivated to follow our instructions. In reality, patients have tremendously different backgrounds and levels of understanding, but we tend to give the same explanations to everybody.

I’m a firm believer that even patients with little formal education will understand you if you express what’s going on in the proper language and use the proper analogies. At the other extreme, ophthalmologists are notorious for abbreviating everything. We have a language of our own, and if you use that language when speaking to patients, they may not have a clue what you’re talking about.

|

| Doctors need to be aware that patients can lose a significant amount of visual field without being aware of it. This 10-2 field of the author’s left eye reveals a dense paracentral defect, but he is rarely aware of the deficit unless he specifically looks for it. |

• Ask about your patient’s daily routine and eye-drop schedule. Most of us work 9 to 5, and we tend assume that our patients do too. In fact, plenty of patients work the night shift; if they do, they have to stay awake a couple of extra hours to see you in the office. You check their eye pressure and it’s nice and low, and you think everything’s great. The reality is, you’re checking the pressure sitting up during their normal sleeping hours. At 3 a.m. when they’re working their shift, their IOP could be twice as high. If you know what kind of a schedule your patients have, you can not only evaluate the pressure reading with that in mind, you’ll have a better idea of when they should be taking their eye drops and medications.

• Ask about the patient’s ability to use the medication at work. Putting in drops at work may be difficult or impossible for some patients. Someone may work on an assembly line, for example, where he literally can’t step away to put in eye drops at the appropriate time, or carrying drops with him might not be permitted. You need to ask about limitations your patient may have in terms of being able to use drops during working hours.

• Inquire about the patient’s support system. I’ve seen elderly patients with poorly controlled pressures who are by and large on their own when it comes to taking their medications. Eventually they go into a nursing home, and suddenly the medications are working perfectly. Without assistance, the patient was either forgetting to take the drops or missing the eye.

In fact, it’s hard to be perfect about using drops even if you’re totally competent. My memory is pretty much intact and I take my drops on a schedule, but there are days when my schedule gets interrupted and I can’t remember whether or not I used the drops. Naturally, sticking to a schedule can be even harder if you’re dealing with memory limitations and you’re on your own. An elderly patient may come in one day with a pressure 8 mmHg higher than normal; if you ask him if he took his drops, he’ll most likely say yes, but I’m not always convinced. So I may bring the patient back in a couple of days or a week and recheck him. If the pressure is back down, if may be worth inquiring about the patient’s support system. (If the pressure is still elevated, then you may have a different problem on your hands.)

• Ask if the patient can manage and afford the drops you’re prescribing. Compliance can be under-mined by a number of factors besides forgetfulness and difficulty getting drops in. Cost is a big factor for many patients. Some patients will flat out tell you, “I can’t afford these medications.” Others won’t tell you that; they simply won’t use them. I think it’s incumbent on us, with the economics of treating being what they are, to inquire about whether the patient can afford the medical treatment.

As you know, compliance can also be undermined by a complex regimen. Sometimes you can save everyone time and money by asking your patients up front if they can manage multiple drops at different times of day. I’ll say, “This is a really tough schedule, will you be able to keep up with this?” Some will say, “Sure, no problem, it’s my eyesight, it’s worth it to me so I’ll do it.” Others will say, “Not likely.” (Of course, in order for this conversation to be meaningful you need to have a combination of good communication and trust so the patient is willing to be honest.)

When you know compliance is going to be difficult for your patient, it’s worth considering surgery. There may be a higher risk up front, but in the long run, getting the pressure under control is what’s going to preserve vision.

Physician, Know Thyself

|

| Getting the patient to understand the disease and reasons for using the medications you prescribe is essential to achieving compliance. Doctors should avoid using one-size-fits-all language or “doctor-speak”; instead, tailor your explanations to the patient’s background. (Quelling a patient’s fears before proceeding will also help ensure comprehension.) |

To truly help patients who have glaucoma, you also need to be aware of your own limitations and biases.

• Remember that we’re here to counsel the patient and provide support and motivation, not just be technicians. There are several reasons we as physicians can lose focus and end up just “doing the job” of getting to the next patient. Not having firsthand experience being a glaucoma patient is, of course, part of the problem for many doctors. But another factor is that the state of medicine and economics today has largely dehumanized the process of medicine, pushing us in the direction of being technicians. In the rush to keep our business afloat we can easily minimize our patient counseling and support. In addition, managing the technical side of medicine is relatively easy in comparison to counseling the patient. However, that doesn’t change the fact that counseling and support are exactly what many of our patients need.

Staying motivated, in particular, can be a challenge for glaucoma patients. They’re tired. Many of them have had this disease for years or decades and they’ve done countless visual fields and taken gallons of eye drops over their lifetime. Some of them are OK with this, but others have a hard time. If you want them to succeed in holding off the disease, you have to remember that their motivation may be waning; you need to encourage them to keep going and stick with the protocol.

Part of that is providing positive feedback: “You did a good job on the visual field,” or “I can tell you’re doing a great job with the drops because your optic nerve looks good and your pressure is stable. Keep up the good work!” The reality is, your patients are the ones taking care of their disease. They live with it every day and do the work of following your protocol, while you only see them a couple of minutes out of the year. You need to let them know that you recognize their efforts and that they’re doing a good job.

Educating the patient is another important aspect of providing proper care, and while this can be time-consuming, it’s mostly only necessary at the outset or when you run into problems. Once patients understand and are compliant with treatment, visits become shorter and easier be-cause patients understand the reason they’re in your office. In the long run it pays off if you spend time educating your patients up front.

• Be aware of your own limitations. All of us come to the office with different levels of experience, knowledge and comfort when it comes to managing different types of eye disease. For the general ophthalmologist, managing glaucoma can be pretty overwhelming given the number of medications and side effects and surgical options; even glaucoma specialists find this challenging and can make mistakes. The point is that there’s no shame in getting advice or passing a patient on to a specialist. I’ve seen doctors hold onto a glaucoma patient until the patient had end-stage disease and then finally send him to a specialist when what could be saved was too little and too late. At the other extreme, I’ve seen patients who were being grossly overtreated, placed on multiple eye drops with minimal, if any, disease.

Another problem is using unrealistic methods to try to achieve results. For example, I’ve seen patients with pressures in the 40s where the ophthalmologist chose to do selective laser trabeculoplasty. The doctor didn’t realize that an SLT laser is not going to drop a pressure that high down into a safe zone and is only delaying a more definitive treatment. I’m not suggesting that a general ophthalmologist should hesitate to treat glaucoma; but on the other hand, limited experience with these drugs and surgeries can lead to trouble, unnecessary expense and poor outcomes for your patients.

There are also issues of time and equipment. Do your really have the time necessary to counsel patients who have glaucoma? Do you have the proper equipment to help diagnose the disease? Just checking pressure and taking a look at the optic nerve isn’t really adequate in this day and age, given that we have the ability to do optical coherence tomography and quantitative measurements of the nerve fiber layer, corneal pachymetry or hysteresis and sophisticated progression analysis. Unless you’re truly equipped to manage glaucoma, you should be asking for a specialist’s help.

That’s why it’s important to be aware of your level of experience and err on the side of using the specialist as a resource. Take the time to make a phone call and ask a question. Then, determine whether the patient needs to be seen by a specialist. Don’t wait until you can’t think of anything else to do and then pass the patient on.

• Beware of bias that glaucoma will inevitably lead to vision loss. Not every doctor is optimistic about glaucoma outcomes in the long run. The problem is, if you believe that eventually everybody goes blind from glaucoma you’ll be willing to accept your patient’s visual field loss getting worse over time, instead of realizing that you need to change your strategy, seek the assistance of a specialist or consider an alternative therapy or surgery. Unfortunately, I’ve seen a lot of this.

| Operating more as a partner with the patient will produce better results. |

I think we can do better. We need to have a high standard for outcomes and a low threshold for changing our approach. If we see a patient getting worse, our conclusion should be that we’re not doing enough. We’re missing something. Maybe the patient is not taking her drops—but it’s up to us to figure that out and do something about it. I believe that if we hold ourselves to a higher standard, we’ll deliver more successful treatments.

• Avoid the authoritarian, paternalistic model of doctoring. In the past, many doctors in all areas of medicine followed a top-down, authoritarian model of how patients should be treated. Ophthalmologists were no exception: “Take this drop and come back in a month, we’ll see what your pressure is.” In this model, little attention is paid to explaining the reasons for treatment, assuaging patient fears or motivating the patient. That’s a recipe for poor outcomes, because a patient who doesn’t have any symptoms or awareness that he’s losing vision is not likely to take a drop that stings, has a lot of side effects or discolors his skin, especially if he doesn’t grasp the reason.

Over the past several decades we’ve seen much improvement in terms of moving our doctor-patient model to a more consensus-based approach. However, ophthalmology is still one of the most conservative areas in medicine in this respect; many of us continue to use a paternalistic, authoritarian approach to treatment. Making a conscious decision to operate more as a partner with the patient will produce better results (and happier patients).

• Respect the patient’s values and wishes. I’ve heard of doctors using the possibility of losing vision as a threat, as if blindness were a punishment for not following the doctor’s directions. Treatment is supposed to be about education, establishing a trust-based relationship and empowering the patient to take responsibility to treat the condition.

The reality is, patients don’t always agree with our recommendations. For example, I’ve encountered patients whose disease has progressed to the point at which they have only hand motion or light perception. I may recommend a procedure, but sometimes the patient wants to just let nature take its course. (The reason might be as simple as the patient not wanting to come to your office every couple of weeks to have something monitored and/or treated.) I think as long as patients understand the consequences of not taking our recommendation, we have to respect their autonomy and values and leave the decision in their hands. The truth is, we’re here in an advisory capacity; our job is to improve quality of life as the patient sees it, not as we see it. People are individuals with different goals and priorities.

Of course, I understand the fear of legal liability when a patient doesn’t want to follow our advice. If the patient says, “No, I don’t want to do that,” you should make extensive comments in the chart about the conversation and the explanation you provided. If you have a good relationship with your patient and her choice leads to a loss of vision, she’s unlikely to blame you.

Medicine at Its Best

Developing glaucoma at an early age gave me a much deeper sense of purpose and direction. It motivated me to push myself in ways I otherwise might not have. It’s given me the chance to study and learn; to travel and teach; and it’s given me a different perspective about life and the obstacles we all face. It has helped me define who I am and what I’m capable of.

I turned 60 this year. Early on, when I decided to pursue this and go to med school, one of my biggest fears was that I wouldn’t be able to continue to be a doctor because of vision loss. That turned out not to be the case, as is often true with the things we fear. Our glaucoma patients share similar fears, but the reality is that most of them will retain their vision as long as they live. As physicians, we should be reassuring them that they have an excellent chance of maintaining their vision with the treatments we can offer (and we’ll undoubtedly have even more effective treatments in the future). It might even be worth noting that obstacles in life, no matter how frightening, sometimes lead us to accomplish great things.

When it comes to empathizing with patients, I have an advantage because I know what it feels like to be on the other side of the slit lamp. But we’ve all faced illness at one time or another (and we prob-ably will again as we get older). Remembering what that feels like can help us not just provide medical advice, but also give our patients the support they need, whether that means assuaging their fears, giving them positive reinforcement for their efforts, helping them work around practical obstacles in their lives or just reassuring them that we’ll be there as long as they need our help.

That’s what medicine is supposed to be about. REVIEW

Dr. Sanchez practices at Glaucoma Consultants of the Capital Region. He has traveled extensively, teaching glaucoma treatment and surgical techniques to ophthalmologists in developing countries around the world.

1. Ang GS, Eke T. Lifetime visual prognosis for patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. Eye (Lond) 2007;21:5:604-8.