People with primary angle-closure glaucoma make up a significant portion of glaucoma patients worldwide; it’s estimated that PACG impacts more than 20 million people. It’s especially prevalent in Asia, where narrower angles are more common than in some other parts of the world.

According to the International Society of Geographical and Epidemiologic Ophthalmology, glaucoma-related disease associated with narrow or closed angles can be classified as occurring in three stages:

- primary angle-closure suspect (PACS), defined as narrow angles but no other signs of angle dysfunction;

- primary angle-closure (PAC), where elevated pressure and/or signs such as peripheral anterior synechiae are present; and

- primary angle-closure glaucoma, where glaucomatous damage to the optic nerve is evident.

By definition, angle-closure suspects don’t have glaucoma, but they do have narrow angles, which means there’s a risk of the angle closing further, potentially leading to glaucoma.

This condition—being an angle-closure suspect—is relatively common, at least in Chinese people; as many as 5 to 8 percent of people over the age of 40 are primary angle-closure suspects. According to the Vellore Eye Survey, about 30 percent of angle-closure suspects progress to having primary angle closure within five years.1 Of those who progress to PAC, 10 to 30 percent then go on to develop PACG over a five-year period. This means that only a small percentage of primary angle-closure suspects end up progressing all the way to angle-closure glaucoma.

The LPI Dilemma

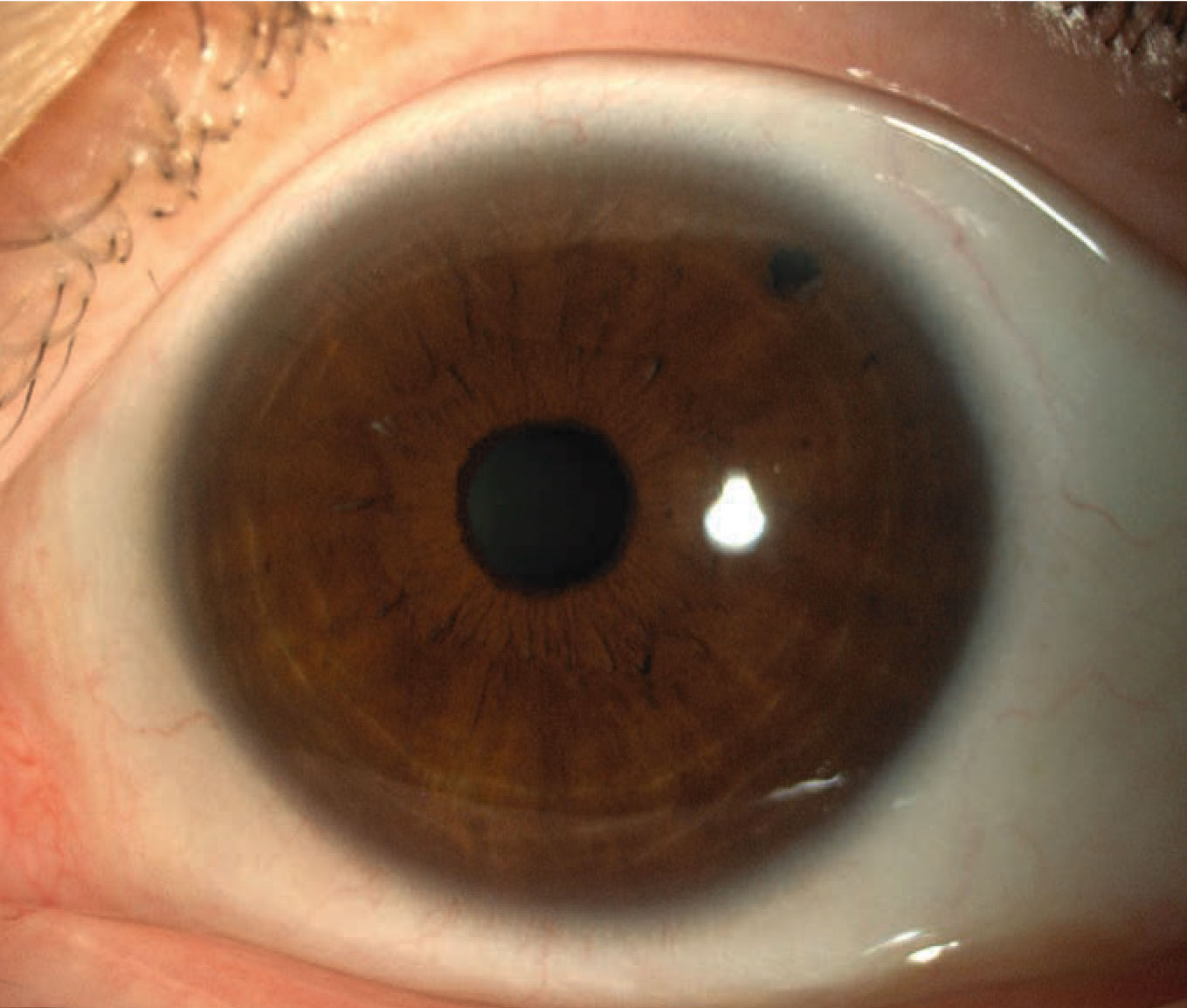

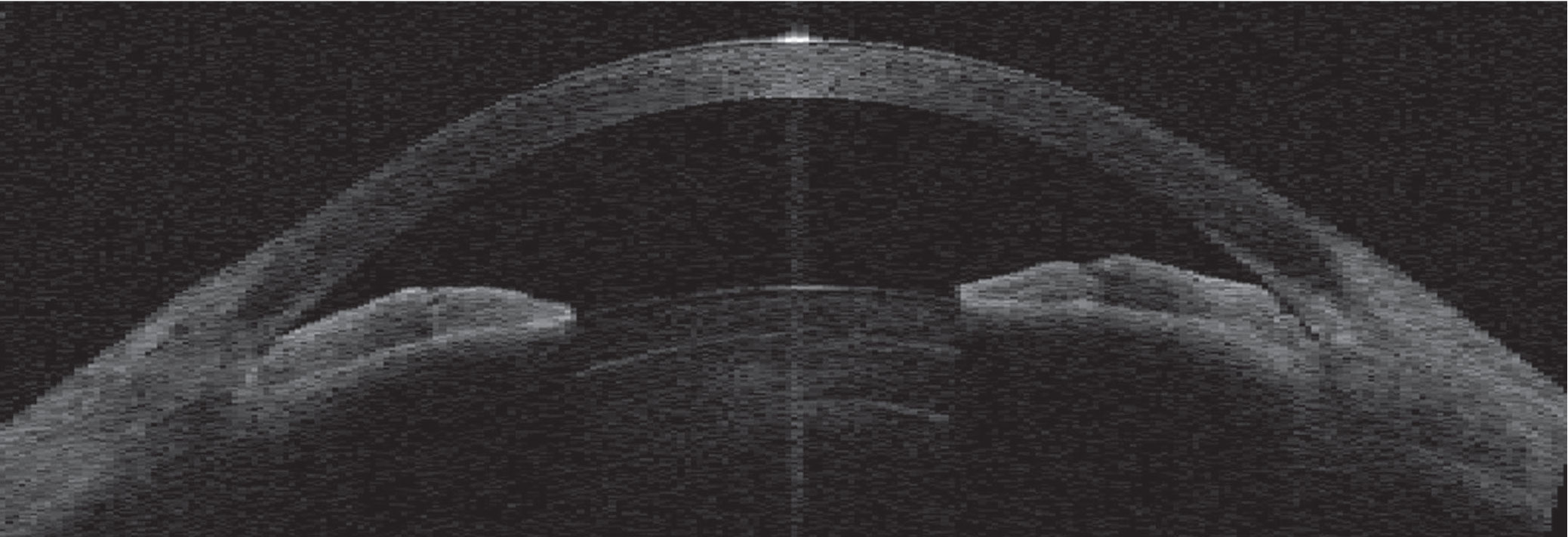

One of the issues that arises when managing a patient with narrow angles—someone who qualifies as an angle-closure suspect—is whether to perform a laser peripheral iridotomy. An LPI can prevent the angle from closing further and helps to mitigate the consequences of angle closure if it occurs. Most important, it reduces the risk of a future acute angle-closure attack, in which the angle abruptly closes and intraocular pressure rises dramatically, leading to pain, and possibly to blindness if left untreated.

|

| A laser peripheral iridotomy lowers the risk of future angle-closure-related damage, but the risk turns out to be small—and some LPI patients are bothered by visual side effects. |

This leaves doctors who are managing angle-closure suspects faced with a dilemma: Should we perform a prophylactic LPI? Like many questions in medicine, deciding whether or not to create an LPI is a question of balancing risk and potential benefit. Doing so might mitigate the risk of suffering and possible blindness if an angle-closure attack were to happen in the future, and the laser itself is generally safe. (Studies, including those described below, found that it had very limited side effects.)

The main issue that can arise following an LPI is that some patients—about 10 percent—experience a visual disturbance; they see a line, or something moving around in their field of vision. The reason for this is that you’ve created a second hole in the iris (besides the pupil), and light passing through that opening can create a visual disturbance. Most patients will get used to this over time, even if they’re initially bothered by it, but a small percentage of these patients find this extremely irritating. (It’s worth noting that if a patient is truly unable to live with this, it’s possible to tattoo the cornea over the LPI, darkening it, so the LPI doesn’t cause the visual disturbance. So far I’ve never had to do that, but it’s an option.)

Unfortunately, the LPI decision also has medico-legal ramifications. No one wants to be sued for not having done the procedure if an angle-closure attack happens later.

Part of the reason this has been a challenging decision to make is that until recently, there’s been very little concrete data about how often someone with narrow angles actually progresses to the point at which an angle-closure attack is a real concern. Now, that’s changed, thanks to two clinical trials addressing this question, one conducted in China, one in Singapore. (I participated in both trials.)

The Chinese (ZAP) Trial

The Chinese trial is called the Zhongshan Angle-closure Prevention trial, or ZAP trial—an appropriate acronym given that it involves a laser—because it was done in the Zhongshan Eye Hospital in Guangzhou. (It was done in collaboration with Moorfields Eye Hospital/University College London, and the Wilmer Eye Institute at Johns Hopkins University.)

One interesting aspect of the ZAP trial is that it randomized treatment and control within each participant, by eye. All subjects had narrow angles in both eyes, so one eye was randomly assigned to receive an LPI while the other eye was the control. The endpoint for the study was primary angle closure, the stage just before glaucoma at which the pressure starts going up, and/or PAS develop, or an acute angle closure attack happens. The aim was to see how often the eye that received an LPI reached that endpoint, compared to the eye that was simply observed. The trial followed patients for six years.

The ZAP trial found, first of all, a very low overall progression rate. That was surprising, because it had been thought that 10 to 30 percent of angle-closure suspects would progress if left untreated. But in the ZAP trial, only about 4 percent of the eyes left untreated progressed during the five-year follow-up period; that translates to less than 1 percent per year. This was far less than expected. However, the study did find that doing the laser reduced the risk by approximately half, to 2.2 percent.

The ZAP trial was conducted to guide population-wide health policy for China. If the study had showed a huge effect, it would have made sense to advocate for population-wide screening for angle closure, as well as population-wide prophylactic LPI. But after seeing the data, that’s no longer being considered. Instead, ophthalmologists are being advised that choosing to simply observe an angle-closure suspect is a reasonable option, even in Chinese people, where the risk of angle-closure glaucoma is much higher than in Europeans.

The Singapore ANA-LIS Trial

Our group conducted a similar trial in Singapore. (Actually, our study started before the ZAP trial, but it took much longer for us to recruit the patients we needed. China is better organized for this sort of project, so recruitment went much faster there; as a result, the ZAP trial was completed before we completed ours.)

The findings from our study were similar to those of the Chinese study. The most striking difference was that we found higher progression rates from angle-closure suspect to primary angle closure: Almost 10 percent of our PACS subjects progressed within five years. However, the benefit of performing an LPI was the same: Doing an LPI reduced the risk by half.

Why did the studies find different rates of progression? Several factors may explain this:

- First, Singapore is a multi-ethnic country; as a result, we had some patients in our study who weren’t Chinese. Thus, the ethnicities of the trial participants were somewhat different.

- Second, we used a different method to recruit patients. Our recruitment was hospital-based; people who came to the eye hospital to be examined or treated for eye problems who had angle closure or narrow angles were referred for the trial. In contrast, recruitment for the Chinese study was done through community-based screening. The researchers went to certain areas of Guangzhou, the capital city of Guangdong Province, and invited everyone over the age of 50 to come for an eye examination. From that exam they picked out the people with narrow angles and referred them for further evaluation. Those who were confirmed to have narrow angles were invited to take part in the trial.

This may have affected the results for at least two reasons: First, people coming to our hospital were likely to have existing eye problems, such as visual acuity issues or mild cataract. Co-existing conditions suggest a vulnerability to future eye problems, including angle closure. Second, most people who come to a free screening, like those in the ZAP trial, are unlikely to have existing eye problems—and the fact that they took advantage of a free screening also suggests that they’re more health-conscious. (In many situations, if you do a health screening, the people who are not well stay home.)

- A third difference between the study populations was that the patients in China had slightly wider angles at baseline than the population recruited for the Singapore trial, based on the clinical exam. (The reason for this baseline difference isn’t clear.) It makes sense that slightly wider angles at baseline would produce a slightly lower rate of progression to primary angle closure.

Despite the differences between the two trials and their results, the conclusion one might draw from the data is similar: Overall, the risk of progression from narrow angles to primary angle closure is quite low.

|

| An angle-closure attack can occur if a patient has narrow angles, leading to a sudden, painful and dangerous rise in intraocular pressure. |

Of course, most of the participants in these studies were of Asian descent, so we can’t directly apply these results to Europeans or Africans; many studies have shown that the prevalence of angle closure is different among Europeans and Africans than among Chinese people. Nevertheless, the findings from these trials should provide helpful information to guide management for all clinicians.

Advising the Patient

Because we now have some concrete data as a reference point, it’s possible to tell your patient the likelihood that he or she will develop angle closure over time, allowing the patient to make a more informed decision. I tell my patients that the risk of developing angle closure is 5 to 10 percent over five years, or 1 to 2 percent per year. I also explain that the laser cuts the risk by half.

In some cases, your patient may ask your opinion about whether or not to proceed with an LPI. This is a challenging position to be in. If a patient asks me that, I probe further to find out if the patient understands the concept of risk. If the patient isn’t keen to have the laser procedure, and clearly understands that the risk is low but not zero, then I’d say skipping the procedure is fine. But if the patient doesn’t seem to understand the concept of risk—or doesn’t want to take any risk at all—then I’d recommend proceeding with the laser. (If there’s no clear reason to go one way or the other, I’d err on the side of doing the laser.)

The kind of relationship you have with the patient also makes a difference. If you have a good relationship—if he or she has been your patient for a long time—it’s a lot easier to make the call, based on what you know about the patient. On the other hand, if you’re dealing with a brand new patient off the street, it’s a lot trickier. In that situation, it’s a lot more difficult to judge how well the patient understands the concept of risk.

Of course, one may still wonder if there’s a reason to recommend that certain specific patients have the procedure done. Ideally, that recommendation would be based on knowing who is most at risk of progressing. For example, it would be great to be able to say, “If your angle is this narrow, you should have the LPI procedure,” or that a patient with an intraocular pressure above a certain value should get the treatment.

Unfortunately, even with the completion of these two trials, that data is limited. Because of the study design, the ZAP trial didn’t find many risk factors. Our Singapore trial did find some risk factors—and that data will be published soon in Ophthalmology—but the most important piece of information would be knowing which patients are fast progressors, since many people with narrow angles don’t progress for years. Unfortunately, the number of participants in our trial wasn’t sufficient for us to detect the fast progressors with any statistical certainty.

Despite this lack of data, there are some patients with narrow angles whose circumstances would make an LPI worth considering. I’d suggest that the following patients be considered for an LPI:

- Those who have symptoms such as pain or headaches. These individuals might be good candidates for an LPI because those symptoms suggest that they may already be having intermittent angle closure.

- Patients with diabetes. The Singapore study showed that diabetes is a risk factor for progressing to angle closure. This might be true in part because these patients are dilated frequently during exams, but it could also be because people with diabetes tend to have some autonomic dysfunction, which could affect the pupil.

- People who are being dilated on a regular basis to monitor other conditions. Those conditions would include macular degeneration and diabetes. Dilating the pupil can provoke an acute angle-closure attack, so regular dilation puts these individuals at greater risk.

- Patients who have poor access to follow-up. If a patient may not be able to easily get help should an angle-closure attack occur, it makes sense to lower the risk as much as possible.

- Patients whose families have a history of angle closure glaucoma. This could indicate a higher-than-average risk.

It’s worth noting that a patient who is having a cataract removed will be less likely to be at risk, because taking out the cataract will also remove the mechanism of pupillary block. Thus, I recommend cataract surgery for many patients with narrow angles and cataract.

As always, we want to do what’s best for our patients; this is simply one of those situations in which it’s difficult to be sure which option really is the best. But given the data from the two trials discussed above, making that determination is now a little bit easier.

Dr. Singh is a professor of ophthalmology and chief of the Glaucoma Division at Stanford University School of Medicine. Dr. Netland is Vernah Scott Moyston Professor and Chair at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Prof. Aung is the Kwan Im Thong Hood Cho Temple Professor of Ophthalmology at Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore, executive director of the Singapore Eye Research Institute and vice chair of research for the Singapore National Eye Center. He has no relevant financial disclosures.

1. Foster PJ, Buhrmann R, Quigley HA, Johnson GJ. The definition and classification of glaucoma in prevalence surveys. Br J Ophthalmol 2002;86:238-42.