One factor adding to the complexity of treating glaucoma is the fact that some common medications our patients may be using can affect their glaucoma—for better or for worse. On the positive side, some evidence suggests that statins and vitamin B3 may help to lower the risk of glaucoma progression. (Having something to offer these patients besides lowering intraocular pressure would be exciting news, since some glaucoma patients will continue to worsen no matter how far we lower their IOP.)

On the flip side, as every ophthalmologist knows, steroids can make glaucoma worse by elevating IOP. This isn’t just true for steroids applied as eye drops or injections in or around the eye; it’s also true for steroid medications taken in pill form, dermatologic steroid creams and even intra-articular injections. And, not surprisingly, many patients don’t realize that some products they’re using may contain steroids.

Steroids aren’t the only medications that can cause trouble for our glaucoma patients, however. Other commonly used drugs, such as some antidepressants, antihistamines and some blood pressure medications, may put a patient at significant risk of vision loss by inducing angle closure. The risk is relatively small, but since an acute angle-closure attack is potentially blinding, it’s worth taking seriously. Also, some drugs such as systemic beta-blockers, widely prescribed for cardiovascular conditions, may decrease IOP. This can confuse our diagnosis and make topical beta-blockers less effective.

Here, I’d like to share some of what we know about the drugs many of our patients may be using and the risks they pose. This is something that all ophthalmologists and optometrists, especially glaucoma specialists, need to be aware of. However, it’s also important information for general providers, such as primary care physicians and internal medicine specialists. We all need to know what to look for—and what to educate patients about.

Impacting Open-angle Glaucoma

First, let’s talk about a bit of possible good news. Some evidence suggests that statins and vitamin B3 may have protective effects for patients with glaucoma:

• Statins. Although it’'s far from conclusive as this point, data from several studies suggests that oral statins—often prescribed for hyperlipidemia, a.k.a. high cholesterol—may be protective against open-angle glaucoma. Two of those studies showed that oral statin use can reduce the risk of development of glaucoma in patients who have hyperlipidemia.1,2 A group of patients who were already on statin therapy for their hyperlipidemia were found to have a significant decrease in the risk of developing open-angle glaucoma. In addition, two other studies found that patients who were on statins had lower visual field progression rates.3,4

Unfortunately, all of these are small studies, and several of them are retrospective reviews, so they can’t show a definitive cause and effect relationship. And while statins are commonly prescribed medications, they’re not without side effects. For these reasons, we need more data before recommending statin therapy to patients with open-angle glaucoma. However, if you have a patient who has hyperlipidemia, or some other systemic reason to take a statin, the risk-benefit ratio might favor taking it. You could certainly talk to the patient’s primary care doctor and discuss this possibility.

• Vitamin B3. Although the evidence for vitamins helping glaucoma patients is still very limited, one study has provided some evidence that high-dose supplementation with vitamin B3 may improve inner retinal function and visual field mean deviation.5 Another study that looked at a Korean population found that people with glaucoma had a lower niacin intake (niacin is a form of vitamin B3) compared to those who didn’t have glaucoma.6 A more recent Phase II randomized clinical trial, published just a few months ago, reported that oral supplementation with a combination of nicotinamide and pyruvate was not only safe, but was associated with a higher number of improved visual field parameters when compared to placebo after two months.7

These studies suggest that statins and vitamin B3 might be helpful for our glaucoma patients. If confirmed, this would be exciting news. Statins are the medication most commonly prescribed to treat hyperlipidemia, and many of our patients are already taking them. Vitamin B3 is an over-the-counter medication with very few side effects or safety concerns. If a patient could just go pick up a supplement and reduce the odds of glaucoma progression or improve their vision, it would be incredible.

Right now, the data is insufficient to say that the risks associated with these medications are outweighed by the potential benefits for glaucoma. However, when you’ve done all you can for a patient from an IOP-lowering standpoint, and you’re looking for anything that might help to save a patient’s optic nerve and vision, the risk of vitamin B supplementation is pretty low.

The Steroid Factor

|

| Many of our patients are unknowingly using medications that contain steroids and may increase eye pressure. Photo: Getty Images. |

Steroid-induced ocular hypertension is a concern we’re all probably familiar with. Steroids can cause microscopic changes within the trabecular meshwork, ultimately leading to increased resistance to aqueous outflow. An increase of at least 6 to 15 mmHg above the patient’s normal IOP is considered steroid-induced ocular hypertension.8-13

The reason steroids are a noteworthy concern is that they’re becoming more and more prevalent in popular, commonly used treatment regimens. Steroids are now frequently used to treat allergies in oral, inhaled, topical or nasal forms, while steroid injections are often given for things like arthritis and joint damage. Dermatologists prescribe steroid creams for a number of issues, and oral and inhaled steroids are prescribed for lung disease such as asthma and COPD. The result is that a large number of people are regularly taking steroid medications that could affect their eyes—and they may or may not be aware of this.

One of the challenges with managing this problem is that the true incidence of steroid-induced ocular hypertension is unknown. Many people being treated with steroids don’t get their IOP checked; they may not even have eye trouble. Based on some studies, we believe about one-third of the general population will have an increase in IOP when taking steroids. However, the rate is going to be much higher in patients who have glaucoma; some studies have suggested that the incidence in glaucoma patients may be as high as 70 to 80 percent.

Specifically, studies suggest that:

— Four to 6 percent of the population would be considered “high responders,” reaching an IOP above 31 mmHg or exhibiting an increase of more than 15 mmHg from baseline.

— About one-third of the population would be considered “moderate responders,” reaching an IOP between 25 and 31 mmHg or exhibiting an increase of 6 to 15 mmHg from baseline.

— Anyone with an IOP less than 20 mmHg on steroids, or exhibiting an increase of less than 6 mmHg from baseline, would be considered a non-responder.

Click image to enlarge. Click image to enlarge. |

One of the medications that I often see causing an IOP increase, especially during allergy season, is Flonase, the intranasal allergy spray. Ninety percent of the patients I talk to about it have no idea that it’s a steroid. Just yesterday I saw a patient who had consistently had a pressure of 19 mmHg for the past two years. Yesterday he came in with a pressure of 35 mmHg. This patient had previously had a pressure increase when using steroid drops, so I knew he was a steroid responder. With that in mind, I asked him about any new medications he was taking; he said he was taking Zyrtec. The allergy reference made me ask him if he was using any nasal sprays. He responded, “Actually, yes. For the past three weeks I’ve been using Flonase almost daily. I’ve never used it before, but it’s working great.” He’s one of the many patients who didn’t realize that Flonase is a steroid. I explained my concerns and asked him to stop using it, if possible. I expect and hope that his pressure will lower rapidly.

Avoiding a Steroid Problem

To help prevent a steroid-induced IOP increase:

• Know which patients are at greater risk. For example:

— Patients with glaucoma have a higher incidence than people who don’t have glaucoma. (However, any person can have a pressure increase in response to steroids, with or without a history of eye disease.)

— Known steroid responders are at greater risk. If your patient’s pressure has risen in response to any steroid in the past, any future steroid could have the same effect. (Note that having no response to topical steroid therapy doesn’t mean that periocular or intravitreal steroids are necessarily safe.)

— If your patient has a first-degree relative with glaucoma, he or she is at higher risk.

— Young patients under the age of 10 and older patients are at greater risk. (Note the bimodal distribution here.) The risk can be great for children; in fact, one study found that the use of steroids accounted for one-quarter of acquired glaucoma in children in India.14

— Other populations at increased risk include patients with high myopia, connective tissue disease and Type I diabetes mellitus.

• Ask about steroid use directly. If you have reason to believe a steroid response may be behind an unexplained increase in pressure, ask the patient about new medications they’re using. Mentioning products by name, or giving examples of things that can be steroids, like inhalers, helps patients figure out if they’re using a steroid. (As noted, Flonase is a common offender.)

• Remember that timing makes a difference. It takes time for a pressure increase to appear, so the less time your patients are on steroids, the less likely they are to have a pressure increase. Most studies say that you have to use a steroid product chronically for three to six weeks for it to cause a pressure increase. However, the time to onset varies. A few cases have documented a pressure increase as early as one week.

The timing here is probably affected by the potency of the steroid, but we don’t have a convenient chart showing how many days it takes for a given medication to cause an IOP increase. (Some medications are fairly well documented in this respect. For example, when using dexamethasone, about 30 percent of glaucoma suspects and 90 percent of POAG patients have an increase in IOP within four weeks.) But of course, every patient is unique.

• Educate your patients. I make sure to mention this risk to my known steroid responders, my glaucoma patients and any other patients who are at high risk. I tell them to be careful any time they start a medication that contains a steroid. I mention that using such a medication for a short time is less risky, but I emphasize that if they ever start a medication and have eye pain or changes in vision, they should call me immediately. (You might consider having a handout on this topic for appropriate patients.)

If the patient in question is a known steroid responder, I ask them to let me know any time they need to start a steroid agent. I explain that if they do start using a steroid-containing medication, I’ll need to check their pressure two to six weeks after starting it. If they have to stay on it, I might check them again every four weeks for a few months.

This protocol has worked very well in my practice. It’s not uncommon for a patient to send me a message saying, “I have back pain and my doctor wants to do a steroid injection. Is that OK?” Or, they may tell me they’re starting a short course of oral steroids for allergy. We then make plans to monitor their pressure as needed.

The point is that educating the patient really works. Patients or providers reach out, and that allows us to have a conversation that also helps make providers aware of the risks.

That brings me to the next point:

• Educate your fellow physicians. Steroid-induced pressure increases are not on the radar of many primary care physicians. At some point in their medical education they learned about it, and they remember it when prompted. But it’s not high on their list of concerns, for very understandable reasons: The risk isn’t great, and they have too many other things to think about!

It’s worth considering getting together with other referring physicians and those you’ll be sharing patients with. If you’re a new provider, it’s a great way for you to meet those colleagues and expand your referral sources. Primary care physicians often run into eye problems, seeing patients with red eyes or eye pain. They also get eye-related questions from their patients and don’t necessarily know how to answer them. So they’re usually happy to get together to get an update on ophthalmology and how they should respond to certain situations. Sharing this information does make a difference; I now have pulmonologists and primary care physicians who reach out to me when one of our joint patients with a diagnosis of glaucoma needs to start a steroid medication.

Of course, some patients will inevitably end up experiencing steroid-induced ocular hypertension, despite our best efforts. But if you share information with your colleagues, more patients will be identified and referred.

Treating Steroid-induced OH

Once you encounter steroid-induced ocular hypertension, how should you proceed?

• If possible, stop the steroid. Depending on the reason the patient is being treated with the medication, this may or may not be feasible. If it's possible, IOP usually normalizes within one to four weeks after cessation of the steroid. (The duration of the steroid therapy will influence how quickly this occurs.)

• If the patient has a steroid repository that’s been placed in the eye, consider excision. However, remember that the steroid depot was placed there for a reason, so consider your options carefully.

• Switch to an alternate steroid formulation. If the problem is being caused by an eye drop, this may be a possibility. For example, durezol, dexamethasone and prednisolone drops are more likely to cause a steroid response than drops such as fluoromethalone or lotemax. So, you may be able to switch the patient from one formulation to another. (If the drug is systemic, consult with the prescribing doctor.)

• If the steroid must continue, consider pressure-lowering treatments. Many of these patients may need to go on topical and/or oral pressure-lowering therapy. Some studies show that selective laser trabeculoplasty can work well in this situation; however, most of these studies are case reports, so it’s somewhat limited data. Nevertheless, for a lot of patients SLT is worth considering, and it makes sense. Steroid-induced IOP increase is caused by an outflow problem, and SLT works on the trabecular meshwork.

• If necessary, perform glaucoma surgery. Many of these patients can be managed on drops, but some patients will need a filtering surgery. This is most common when the patient is receiving intraocular or periocular steroid injections, or requires chronic steroid therapy for other ocular issues. In these cases the patient needs the steroid, so we have to manage the IOP.

The other situation that may require a more permanent solution is a patient whose pressure never decreases after cessation of the steroid agent. This happens in about three percent of cases.

Meds and Angle Closure

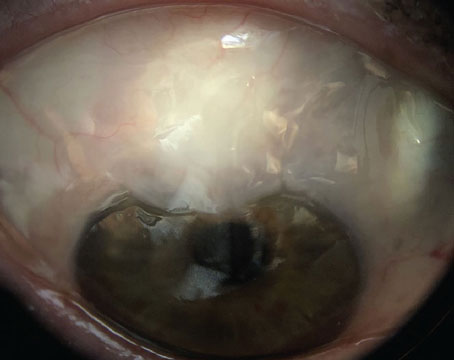

Another issue to be aware of is that some commonly used medications can cause angle closure. (When this happens, the angle closure is usually bilateral.)

There are two causative mechanisms of action. One is pupillary block, where the pupil dilates and gets stuck to the lens behind it, causing pupillary block. This, in turn, causes angle closure. The other mechanism of action is anterior shifting or rotation of the lens-iris diaphragm, which closes off the angle.

It’s important to distinguish between these, because the appropriate treatment depends on which etiology you’re dealing with. If the patient’s medication causes pupillary block, you can treat the pupillary block with a laser peripheral iridotomy. You may also try to get the patient off the medication in question, but performing the LPI to break the pupillary block will cause immediate opening of the angle and lowering of the pressure. (It’s true that an LPI can cause visual symptoms in some patients, but the risk of losing vision from the angle closure is far worse than any risk associated with an LPI.)

The other etiology is anterior shifting of the lens-iris diaphragm. This condition can be more difficult to diagnose. (Performing ultrasound biomicroscopy can help make this diagnosis, but this isn’t always readily available to providers.) In this situation, an LPI won’t really help, so the primary way to address this is by stopping the medication. You may also try cycloplegia; cycloplegics such as atropine have been shown to deepen the anterior chamber.

No matter which etiology you’re dealing with, depending on the pressure, the patient may need IOP-lowering medications and/or surgery to control the pressure.

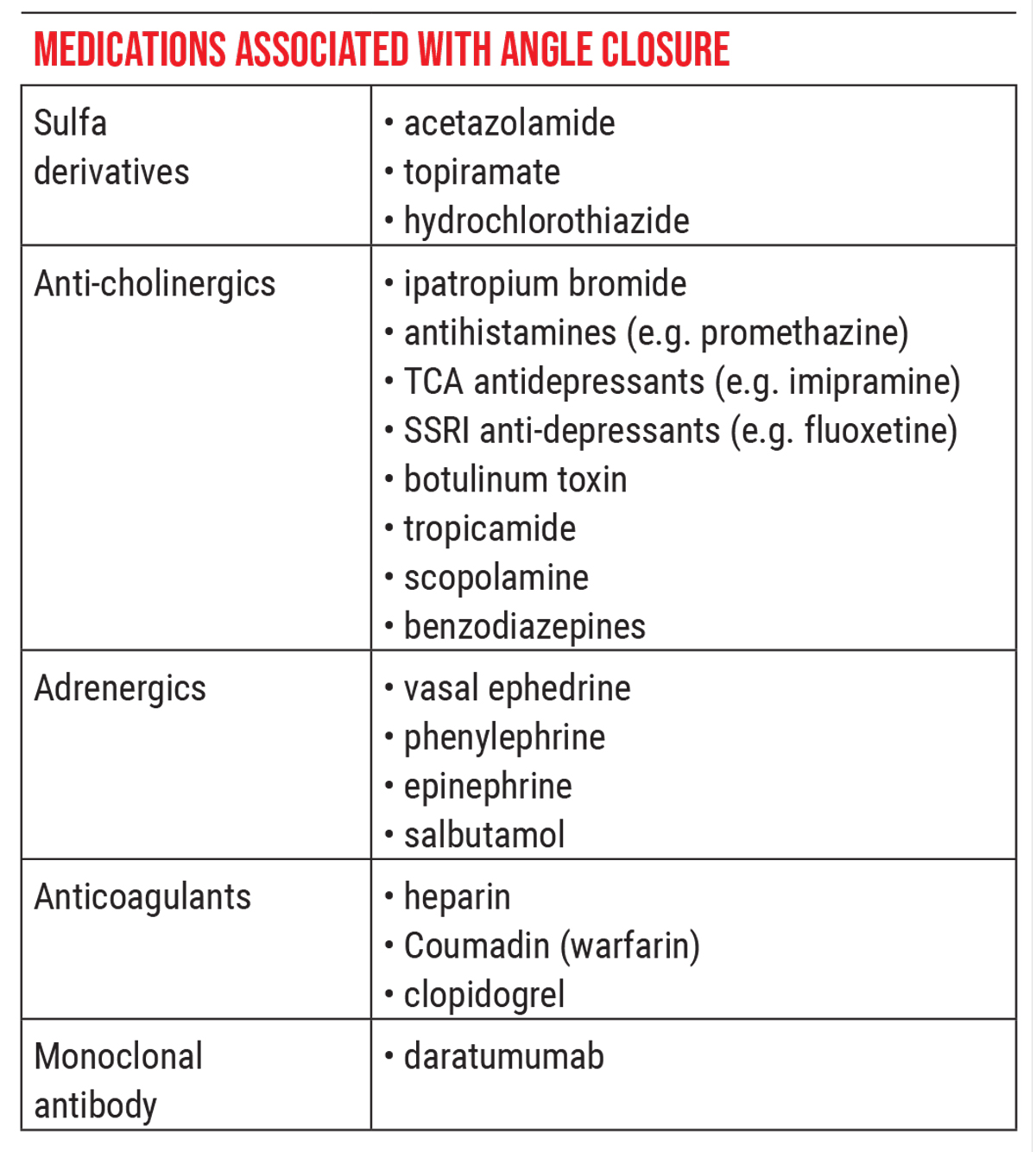

Problematic Meds by Category

The list of medications that can cause angle narrowing is long. One way to remember them is in terms of the category or class of medication. The list below contains some of the key offenders. (Note: This list is by no means comprehensive.)

• Sulfa derivatives. These include topiramate (Topamax), hydrochlorothiazide, which is a very commonly prescribed blood pressure medication, and acetazolamide (Diamox). The last drug catches many ophthalmologists off guard because Diamox is routinely used to treat angle-closure glaucoma by lowering intraocular pressure. However, in rare cases, Diamox can actually worsen angle closure by causing anterior rotation of the lens-iris diaphragm. It doesn’t happen very often—I’ve only seen it once. But it’s something to keep in mind: A drug we use to treat angle closure can sometimes make it worse.

Topiramate is a medication I’m encountering with more and more patients. Usually it’s taken to treat migraines, idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), seizures or bipolar disorder. It can cause ciliary body effusions, which in turn cause anterior shifting of the lens-iris diaphragm.

In this case, you have to be cautious about stopping the medication. If a patient has been on Topamax for some period of time, you can’t stop the medication abruptly; you have to taper it off. That involves getting the patient’s neurologist, primary care physician or other prescribing provider involved with stopping the medication. The caveat is that if Topamax is at fault, the angle closure usually happens within the first few weeks of using the medication, and in that situation, you usually can stop it abruptly without serious consequences. However, my mantra is, if Topamax is causing the problem, I get the prescribing doctor involved immediately.

• Anti-cholinergics. Many of our patients take medications in this group, including:

— ipratropium bromide, a medication used to treat COPD;

— antihistamines (e.g., promethazine);

— several classes of antidepressants, including TCA antidepressants (e.g., imipramine) and SSRI anti-depressants (e.g., fluoxetine);

— tropicamide, an ophthalmic drop;

— scopolamine, often used to address motion sickness;

— benzodiazepines, which are anti-anxiety medications; and

— botulinum toxin (Botox).

These can cause pupillary block, which can be treated with pressure-lowering therapy and an LPI.

• Adrenergics. Problematic adrenergics include nasal ephedrine, phenylephrine, epinephrine and salbutamol. These are commonly found in cough and cold medications—easily accessible, over-the-counter medications. They traditionally cause pupillary block, which, again, can be treated with pressure-lowering therapy and an LPI.

• Anticoagulants. These include heparin, coumadin and clopidogrel, also known as Plavix. These drugs can cause an anterior shift of the lens-iris diaphragm, so an LPI won’t help. We need to get these patients off of these medications, which usually involves getting the prescribing doctor involved.

• Monoclonal antibody. The causative medication here is Daratumumab. This is a relatively new medication that’s primarily used for the treatment of multiple myeloma. It can cause anterior choroidal effusions and anterior rotation of the ciliary body. There have been a few case reports of this since it started being used a few years ago, two of which came from our university.

Daratumumab can cause a significant myopic shift, which is often associated with anterior shifting of the lens-iris diaphragm. Our group published about a patient who experienced this.15 She’d already had cataract surgery, but during her infusion she noticed that she couldn’t see across the room. At the same time, she suddenly found that she could read a book without her glasses, which she hadn’t been able to do since her cataract surgery years prior. Her oncologist rightly said, “Go see your eye doctor!” Luckily, we were able to diagnose the problem and get her off the medication before she developed a chronic angle closure or any pressure issues.

As with sulfa derivatives and anti-coagulants, Daratumumab can cause an anterior shift of the lens-iris diaphragm, so an LPI won’t help much.

Spreading the Word

How should you educate patients and fellow providers about these concerns? My approach is to discuss the risks with all patients who have narrow angles or are at risk of angle closure, including high hyperopes, who tend to be at risk of angle closure, and anyone with a history of angle closure. When discussing this, I mention specific medicines and classes of medicines. For example, I’ll say, “If you ever have to take a cough or cold medicine, an antidepressant or a migraine medication, and you develop eye pain or blurred vision afterwards, call me immediately, and let your prescribing doctor know as well.”

Of course, you won’t be able to prevent all such events. If you encounter a patient with sudden-onset bilateral shallow anterior chambers or bilateral angle closure, ask if they’re taking the relevant medications. Be specific and go down the list. These are common medicines, and patients may confirm recently starting one of them. As noted, the problem usually arises within a few weeks of starting the medication, and it should be bilateral. Keep it near the top of your differential when you see new bilateral angle closure.

Note: In rare cases, medication-related eye problems may not be bilateral. For example, taking a systemic or nasal steroid would normally affect both eyes, but if a patient has severe glaucoma in one eye and not the other, you may only see a significant response in the glaucomatous eye. Another example: If a medication causes angle closure, but a patient has had cataract surgery in only one eye, the eye that has already had cataract surgery might be naturally deeper and therefore at a lower risk of angle closure. In that case, the angle closure could be unilateral.

In terms of talking to other providers, pretty much every neurologist who prescribes topiramate is aware of this risk. I’ve treated several people with topiramate-induced angle closure, and all of their neurologists knew it was a risk. (In fact, the patients were also aware that it was a risk; they simply saw it as being worth the risk.) This makes it an easy conversation to have with those providers. Just reach out to them and they’ll help you get the patient off the medication.

The Big Picture

To summarize:

• Be on the lookout for steroid-induced ocular hypertension.

• Ask about steroid use in your glaucoma patients, especially patients who come in with a pressure that’s suddenly higher than before.

• Remember that it’s not just ocular and periocular steroids that can have an effect. Any steroid can—and every patient is unique.

• Remember that bilateral angle closure is a strong clue that a medication may be responsible. Ask the patient about specific medicines that are known to be associated with this. Try to deduce the mechanism of action based on the medication the patient is taking, to help you steer your treatment more effectively.

• Be on the lookout for more data on statins and vitamin B3 use in glaucoma patients. (Hopefully we’ll have something besides pressure lowering that we can offer to our glaucoma patients in the future.)

• Whenever possible, take the time to educate your patients and fellow providers about the risks associated with these medications. Of course, we all have very busy clinics, so you may not always have a lot of time to do so. But whenever you can, do it.

This article has no commercial sponsorship.

Dr. Capitena Young is an assistant professor at the Sue Anschutz-Rodgers Eye Center at the University of Colorado. She reports no financial ties to any product discussed in this article.

1. Stein JD, Newman-Casey PA, Talwar N, et al. The relationship between statin use and open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2012;119:10:2074-2081.

2. Kang JH, Boumenna T, Stein JD, et al. Association of statin use and high serum cholesterol levels with risk of primary open-angle glaucoma. JAMA Ophthalmol 2019;137:7:756-765.

3. Leung DY, Li FC, Kwong YY, et al. Simvastatin and disease stabilization in normal tension glaucoma: A cohort study. Ophthalmology 2010;117:3:471-476.

4. Whigham B, Oddone EZ, Woolson S, et al. The influence of oral statin medications on progression of glaucomatous visual field loss: A propensity score analysis. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2018;25:3:207-214.

5. Hui F, Tang J, Williams PA, et al. Improvement in inner retinal function in glaucoma with nicotinamide (Vitamin B3) supplementation: A crossover randomized clinical trial. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2020;48:7:903-914.

6. Jung KI, Kim YC, Park CK. Dietary niacin and open-angle glaucoma: The Korean national health and nutrition examination survey. Nutrients 2018;10:4:E387.

7. De Moraes CG, John SWM, Williams PA, et al. Nicotinamide and pyruvate for neuroenhancement in open-angle glaucoma: A phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol 2022;140:1:11–18.

8. Feroze KB, Khanzaeni L. Steroid Induced Glacuoma. [Updated 2021 Jul 17]. In: Stat Pearls [Internet] https://www.ncbu.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430903/.

9. Phulke S, Kaushik S, Kaur S, Pandav SS. Steroid-induced glaucoma: An avoidable irreversible blindness. J Curr Glaucoma Pract 2017;11:2:67-72.

10. Kersey J, Broadway D. Corticosteroid-induced glaucoma: A review of the literature. Eye 2006;20;407–416.

11. Lachkar Y, Bouassida W. Drug-induced acute angle closure glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2007;18:2:129-33.

12. Yang MC, Lin KY. Drug-induced acute angle-closure glaucoma: A review. J Curr Glaucoma Pract 2019;13:3:104-109.

13. Ah-Kee EY, Egong E, Shafi A, et al. “A review of drug-induced acute angle closure glaucoma for non-ophthalmologists.” Qatar Med J 2015;10;6.

14. Kaur S, Dhiman I, Kaushik S, Raj S, Pandav SS. Outcome of ocular steroid hypertensive response in children. J Glaucoma 2016;25:343-347.

15. Strong A, Huvard M, Olson JL, Mark T, Capitena Young C. Daratumumab-induced choroidal effusion: A case report and review of the literature. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2020;20:12:e994-e997.