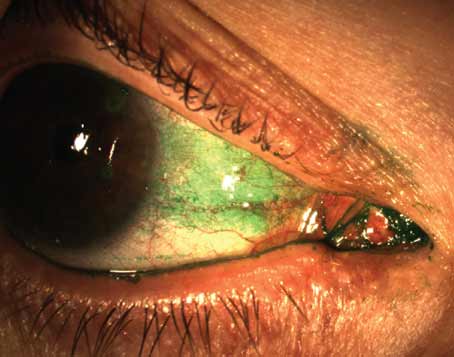

To call pterygium a perennial thorn in physicians’ sides would be an understatement: They’ve been fighting the condition for thousands of years, judging by pterygia’s appearance in Egyptian hieroglyphics. Thankfully, techniques have advanced greatly since then, and surgeons say pterygium’s recurrence rate is very low when the proper techniques are used. In this article, corneal specialists share their time-tested techniques for removing pterygia and reducing its rate of recurrence.

Surgical Indications

Physicians say that many pterygia can be managed medically, and don’t always require surgery.

“Lubrication is sometimes helpful when a patient presents with a pterygium,” says Wills Eye Institute’s Christopher Rapuano, MD. “NSAID drops can also help. If the patient has associated allergy, drops can help for that, as well. If it’s dryness, Restasis might be useful. Sometimes decreasing their contact lens wear or using artificial tears when their contacts are in can be helpful. Rarely will steroids be used, and if we do use them it’s just for a short term.” The medical treatment won’t eliminate the pterygium, says Dr. Rapuano, but it can cause the active inflammation to improve and possibly cause the pterygium to be less “three-dimensional” on the eye.

When Surgery’s Required

However, surgeons say, a small percentage of pterygia will be bad enough to need surgical excision. Here are the criteria experts use when considering the possibility of surgery.

“For me, there are three categories of indications for removing pterygia,” says Sadeer Hannush, MD, attending surgeon on the cornea service at Wills Eye Institute and assistant professor of ophthalmology at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. “The definite indications include cases when the pterygium is interfering with vision, usually by encroaching over the visual axis or pupillary aperture, or by creating significant astigmatism. Also, usually in cases of recurrent pterygia, there can be restriction of the movement of a muscle—usually the medial rectus—due to scarring. This restriction may cause double vision. The next category of indications is ‘probable’ indications. This includes documented growth of the pterygium, even though it may not be visually significant.

For example, if a referring physician whom I trust tells me that the pterygium has grown a millimeter over the past year, that’s enough of a reason for me to consider removing it. Second, chronic recurrent inflammation is a probable indication. The last category of indications is the ‘possible’ one, and mainly consists of cosmetic reasons, such as when the patient says, ‘I don’t like the way this looks and I want it out.’ I think that can sometimes be a reasonable indication.”

|

Surgical Pearls

Surgeons offer tips for the various stages of pterygium removal aimed at both achieving a good result and decreasing the risk of recurrence.

• Anesthesia. Though many surgeons remove pterygia under local anesthesia, a nerve block can sometimes have advantages. “I normally do them under a block,” says Louisville, Ky., surgeon Asim Piracha. “I don’t like the patient squeezing.”

• Excising the pterygium. To begin, some surgeons place a stay suture. “I place a 6-0 Mersilene stay suture in the superior limbus,” says Dr. Rapuano. “That allows me to draw the cornea and position the globe where I want to for the surgery.”

Surgeons then address the pterygium itself. “I mark the lateral aspect of the pterygium,” says Dr. Piracha. “Then I inject subconjunctival lidocaine with epinephrine.” Physicians say the injection helps excision by ballooning up the pterygium. “I typically grasp the pterygium from the anterior portion and tilt it back posteriorly using a 0.12 forceps to peel it off,” continues Dr. Piracha. “I prefer to peel it rather than shave it or perform a lamellar dissection with a blade. The reason for this approach is I know I’m not going to get deep in the stroma and remove corneal tissue.”

Some surgeons have success with scissors and blade excision on the corneal side of the pterygium, though. “After I balloon the pterygium up with local lidocaine, I excise it with Westcott scissors down to bare sclera,” explains Dr. Rapuano. “I then take a 57 blade and gently excise the pterygium from the corneal side, trying to get under the plane of the pterygium and not excise much corneal tissue. I place the blade flat on the cornea and push it all the way to the limbus until the pterygium is free.”

In Dr. Piracha’s approach, after he’s peeled off the pterygium to the limbus, he’ll then use Westcott scissors to undermine it away from the sclera in a manner similar to Dr. Rapuano’s. “I don’t get very aggressive with the conjunctival excision, because if you pull it and cut it, you go all the way down to the caruncle and that causes a cosmetic issue,” he says. “But I do aggressively remove the thick, adherent Tenon’s, because I feel that the conjunctiva travels on the Tenon’s in these cases, and if you remove the Tenon’s the conjunctiva won’t come back. A word of caution, though: Be aware of the medial rectus or lateral rectus muscle, especially the medial. You don’t want to excise the muscle in the process of excising Tenon’s. If you pull up on the Tenon’s and tent it up, you tend to separate it from the muscle. This not only avoids cutting the muscle but also reduces the bleeding.”

After the pterygium’s removed, surgeons like to smooth the area. “Once I’ve taken off the entire pterygium and sent it to pathology, I take the diamond burr and smooth out the limbal area and the cornea with it,” says Dr. Rapuano. “However, you don’t want to thin the cornea too much or make it too irregular. I think the smoother the limbus and cornea are, the lower the chance of recurrence.” Many surgeons will also apply some light cautery to the area at this point to facilitate visualization of the sclera.

• Use a graft. In addition to a thorough removal of the pterygium, surgeons say another key to preventing recurrence is using a graft over the pterygium site to act as a barrier to regrowth.

Surgeons say that for years the treatment for pterygia involved leaving bare sclera, but they now know this method leads to the highest rate of recurrence. The use of conjunctival autografts became popular, but then amniotic membrane transplantation supplanted autografts for a time as the preferred approach, surgeons say, due to the time required to perform the conjunctival autograft. However, due to their low rate of recurrence, conjunctival autografts have become very popular again. Studies report a recurrence rate with bare sclera as high as 76 percent,1 while most of those which use grafts of either conjunctiva or AMT report rates below 10 percent, with the former often having a slightly lower rate.2-4

Surgeons say both conjunctival autografts and AMT grafts yield excellent results, and that the final decision often comes down to surgeon preference and the ability to tolerate each method’s slight disadvantages. “Usually, I’ll use one or the other,” says Dr. Hannush, “knowing that the literature is more in favor of the use of a conjunctival autograft in terms of decreasing recurrence rate, but AMT is a little easier to do, takes less surgical time and, at least in the first few weeks postop, looks better cosmetically.

However, my rate of recurrence is very low with both techniques, and my sense is that the higher recurrence rate with AMT reported in the literature may be technique-dependent.” AMT is also useful in cases where there isn’t a lot of conjunctiva to work with, such as in patients with previous glaucoma surgeries. Proponents of conjunctival autograft also note that, in addition to a slightly higher rate of recurrence, another disadvantage of AMT is cost, since it needs to be purchased, while the patient’s conjunctiva is free.

|

In the following sections, users of conjunctival autografts and AMT share their grafting techniques and tips for reducing recurrence.

• Conjunctival autografts. Dr. Piracha says proper measurement beforehand helps cut a graft that will be effective. “I measure the exposed scleral bed, especially the limbal aspect, with calipers and then excise a graft from the superior conjunctiva that’s the same size as the bed,” he says. “I prefer to err on the side of a larger graft, because it will put less tension on the graft and the original conjunctiva. I don’t want to slide the conjunctiva in too much; I want the conjunctiva where the pterygium was to fall back, while I fill the space with the conjunctival autograft.

“To prepare the superior graft, I mark it first,” Dr. Piracha continues. “I then do a sub-conjunctival injection of lidocaine with epinephrine to balloon up the conjunctiva. I try to inject it between conjunctiva and Tenon’s, which allows me to prepare the conjunctival graft without removing Tenon’s. I’ll make two vertical cuts on the lateral margins of the conjunctival graft, then undermine the tissue, separating conjunctiva from Tenon’s with Westcott scissors. Then, I’ve got two cuts and the conjunctiva still adherent at the limbus and, posteriorly, parallel to the limbus.

“Then I cut the posterior aspect of the autograft and fold it forward to the limbus,” Dr. Piracha continues. “I dissect off Tenon’s but avoid making buttonholes in the graft. I cut the graft at the margin of the limbus, fold it onto the cornea with the Tenon’s-facing side up, then rotate it to the point where its limbal portion meets the limbus of the cornea. I dry the scleral bed in preparation for use of Tisseel glue. I’ll put the thrombin component of Tisseel on the scleral bed and the fibrinogen on the undersurface of the graft. Then, I grab the posterior portion of the conjunctival graft and flip it over, placing it on the scleral bed. That’s when the thrombin and fibrinogen begin to congeal.” Dr. Piracha also uses two cyclodialysis spatulas to squeegee the graft to stretch it over the scleral bed and remove excess Tisseel. “If there’s still a gap between the existing conjunctiva and the graft, I’ll fill it in with glue,” he adds. “And then I’ll slide the existing conjunctiva toward the graft to meet it. If there’s a corneal epithelial defect, I’ll cover it with Tisseel and put a bandage contact lens on the eye to help with comfort.”

Though many surgeons rely on tissue adhesive to keep the graft in place, some will place two sutures at the limbus to help, as well. Surgeons say nylon sutures are less inflammatory, but need to be taken out later, while Vicryl sutures absorb on their own, yet cause more inflammation.

• Amniotic membrane grafts. New York City surgeon Penny Asbell prefers AMT with adjunctive mitomycin-C. “For me, AMT is convenient, and the form I use is freeze-dried, so I can use it when I’m ready,” she says. “It doesn’t have to be used within a certain period of time like the fresh form. It’s easier to handle than a conjunctival autograft, which becomes flimsy and difficult to keep in the right orientation.” She says the freeze-dried membrane can be kept for years while the fresh, cryo-preserved membranes have a shelf life of about six months.

“The key to success with AMT is accurately measuring the area you want to cover,” explains Dr. Asbell. “We measure it in two dimensions and then add two millimeters to the measurements. Also, be careful to measure what you want to cover. We cut it as a square or rectangle but are aware that rounded corners will be more useful than sharp ones in order to fit in with the defect you’ve made. Once it’s down, I’m looking to tuck that membrane under the conjunctiva to form a seal. I have a little amniotic membrane overlap onto the cornea to help that heal as well.

“I put the AMT on dry and then trim it as needed,” Dr. Asbell continues. “I then wet it with BSS, which keeps it in place. Then I’m ready for the tissue glue.”

• Mitomycin-C. The use of the antimetabolite with pterygium excision is somewhat controversial. Many surgeons use it only for recurrent cases, if at all, due to the risk of scleral ischemia. Other surgeons, though, especially those who use AMT, appreciate MMC’s effect on lowering their rate of recurrence. Dr. Asbell uses it with her AMT grafts and says it’s given her good results. “I use mitomycin-C prior to placing the amniotic membrane,” she explains. “I haven’t had any problems with it. I use 0.02% mitomycin for approximately one to three minutes.”

• Postop follow-up. Surgeons say the postop steroid regimen for pterygia is key to stamping out recurrences.

“Normally I use a combination steroid-antibiotic ointment until the surface heals,” says Dr. Hannush. “And I keep patients on a steroid for at least three months, preferably longer, on a tapering regimen.” Dr. Rapuano agrees, saying, “I slowly taper the steroid over several months, watching for increased intraocular pressure or other adverse events. I’m convinced that a rapid steroid taper increases the recurrence rate.”

Managing Recurrences

Surgeons say that though proper technique and use of a graft has gotten their recurrence rates down to well below 10 percent, occasionally a pterygium will recur and require excision. Here’s how they handle a recurrence when it occurs.

“My approach depends on what the patient underwent the first time,” says Dr. Rapuano. “If they had AMT or no conjunctival autograft, I’ll use a conjunctival autograft technique. If they had an autograft previously, sometimes I can get good conjunctiva superiorly if it isn’t too scarred. If I can, I’ll use my conjunctival graft technique with the addition of 0.02% mitomycin-C, concentrated under the conjunctiva that remains, and putting a little on the sclera too, for two minutes. Then I’ll complete my graft. If I can’t get good conjunctiva either superiorly or inferiorly, I’ll use mitomycin and then use AMT to cover the bare sclera.”

Dr. Hannush says that, with recurrent pterygia, he usually uses a conjunctival autograft if AMT was used the first time around, and vice versa. In excising a recurrent pterygium, he employs a special method of applying MMC to reduce possible damage to the underlying sclera from this antifibrotic agent. “To decrease the chance of contact of the mitomycin with the sclera, I place a piece of glove paper under the conjunctiva to protect the sclera,” he says. “I then apply the mitomycin to the underside of the conjunctiva, trying to avoid letting it seep onto the sclera.”

From healers in ancient Egypt to the high-tech, well-equipped physicians of today, pterygia have remained a constant problem. With the right approach and a good graft, though, surgeons say you can often lay your foe to rest.

1. Mourits MP, Wyrdeman HK, Jurgenliemk-Schulz IM, et al. Favorable long-term results of primary pterygium removal by bare sclera extirpation followed by a single 90 strontium application. Eur J Ophthalmol 2008;18:3:327-31.

2. Lian WH, Li RR, Deng XY. Comparison of the efficacy of pterygium resection combined with conjunctival autograft versus pterygium resection combined with amniotic membrane transplantation. Yan Ke Xue Bao 2012;27:2:102-5.

3. Zheng K, Cai J, Jhanji V, Chen H. Comparison of pterygium recurrence rates after limbal conjunctival autograft transplantation and other techniques: Meta-analysis. Cornea 2012 Jan 6 [Epub ahead of print]

4. Celeva V, Stankovic G, Zdravkovska M. Comparative study of pterygium surgery. Prilozi 2011;32:2:273-87.