The evaluation and diagnosis of dry eye is challenging. It’s a multifactorial condition, and reported symptoms aren’t always consistent with ocular surface changes. Generally, diagnosis of dry-eye disease entails patient history and slit-lamp examination, with additional testing performed as needed.

According to Stephen Pflugfelder, MD, who’s in practice at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, it’s important to evaluate both signs and symptoms. “A patient could be a grade 4 from symptoms alone but not really have any signs, or he or she could be a grade 4 with signs but have no symptoms. In either case, treatment should be tailored to the severity, and it will determine how aggressive you want to be and what your options for therapy will be,” he says.

Patient Symptoms

Christopher J. Rapuano, MD, who’s in practice at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia, recommends starting with a history and asking about patient symptoms. “Certain symptoms go more along with dry eye than with other conditions,” he says. “The first is the time of day when the patient is experiencing symptoms. Dry-eye symptoms tend to be worse toward the end of the day or during or after concentrated visual tasks, such as reading, computer work, watching screens and driving. Environment is also important. Do patients work in an air-conditioned office or where a fan is blowing on them? Is it a cold, dry day? Those things clue me in to the diagnosis of dry eye. The severity of the symptoms typically goes along with the severity of the dry eye.”

He adds that the importance of the patient’s history can’t be overemphasized. “I think that we miss a lot if we’re not listening to the patient’s symptoms,” Dr. Rapuano says. “Some of those will really help us determine whether it’s more dry eye, whether it’s more blepharitis, and whether it has a neurotrophic component to it. We also need to find out whether the patient has a history of herpes or diabetes. Many diabetic patients have ocular surface issues, and it may be related to some of the neurotrophic aspects of their long-term diabetes.”

When assessing symptoms, Dr. Pflugfelder explains that there’s no universal questionnaire, but that many ophthalmologists have their own questionnaires. “The ones that seem to be used the most are the Allergan OSDI and visual analog scales, like the Symptom Assessment in Dry Eye (SANDE),” he says. “DEWS grades symptoms on a scale from 1 to 4. Symptoms include discomfort, severity and frequency, and these are two questions on the SANDE questionnaire. The first one is to grade the severity of dry eye, basically from 0 to 100, and then the frequency is the second question. In grade 1, it would be mild or episodic, occurring under environmental stress, and that would range all the way to grade 4 with severe and disabling and constant symptoms, so that would probably be 100 on the questionnaire.”

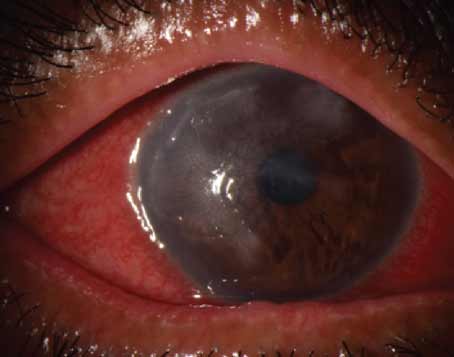

|

| Figure 1. Conjunctival lissamine green staining with corneal filaments. (Courtesy Stephen Pflugfelder, MD) |

Studies have shown the OSDI and the SANDE questionnaires are equally effective. In one study, data collected from the SANDE questionnaire showed a significant correlation and negligible score differences with those from the OSDI, suggesting that the SANDE visual analog scale-based questionnaire has the potential to provide clinicians with a short, quick and reliable measure for dry-eye symptoms.1

The study included 114 patients with dry-eye disease. All patients were administered the OSDI and SANDE questionnaires at baseline and follow-up visits. The correlations between both questionnaires’ scores were evaluated using the Spearman coefficient, and their clinical differences were assessed using Bland-Altman analysis.

At the baseline visit, the OSDI and SANDE questionnaire scores significantly correlated. Additionally, a significant correlation was found between changes in the OSDI and SANDE scores from baseline to follow-up visits.

Signs

Dr. Rapuano notes that slit-lamp findings are crucial for grading dry eye. “Fluorescein stain is important. The more fluorescein staining there is, the less healthy the ocular surface and the worse the dry eye,” he says. “And, I’ll often do lissamine green staining of the cornea, but especially of the conjunctiva. That’s important to me because some patients who have a lot of symptoms have a great-looking cornea with no fluorescein staining, but they have tons of lissamine green staining of the conjunctiva, and that goes along with dry eye. Before we were performing consistent lissamine green staining, we were missing a lot of these patients.”

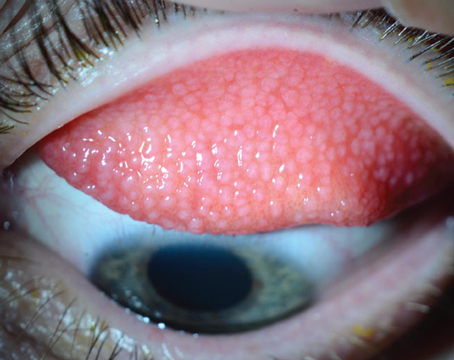

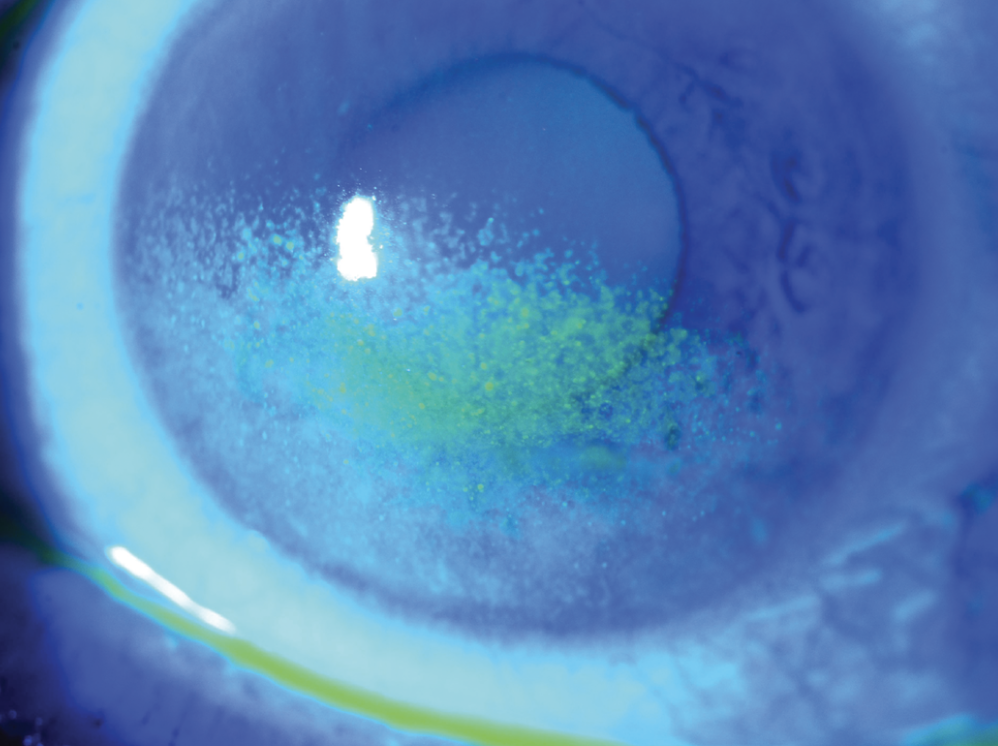

|

| Figure 2. Conjunctival lissamine green staining can catch patients with symptoms but no corneal stain. (Courtesy Stephen Pflugfelder, MD) |

He often performs a Schirmer’s test on patients he is seeing for the first time. “I often don’t repeat it unless I need to, but it can be very helpful when evaluating first-time dry-eye patients,” Dr. Rapuano adds. “It’s helpful if it’s above 15 or below 5. In the 5 to 15 range, it’s often not super helpful, but the highs and the lows give me some idea of tear production. If it’s high, I’m thinking maybe it’s really not dry eye. If it’s really low, I’m thinking there’s definitely some aqueous deficiency going on here.”

According to Dr. Pflugfelder, another criterion is visual changes, which can range from nothing to constant and possibly disabling. “There could also be a decrease in the patient’s actual visual acuity. The next item is conjunctival injection, ranging from none or mild to 2+,” Dr. Pflugfelder says. “Again, there are schemes to grade injection, like the Waterloo scale. Conjunctival staining can range from none to marked, and corneal staining can range from none to severe punctate and confluent staining. DEWS criteria grade corneal signs from none to grade 4, which would be filamentary keratitis, mucus clumping, adherent debris or corneal ulceration. Then, we evaluate lids and meibomian glands. Grade 1 would mean meibomian gland disease is variably present, and grade 3 would be that it’s definitely present and moderate to severe. The next item is fluorescein tear breakup time. Grade 1 would be variable, and grade 4 would be immediate breakup. The last criterion is the Schirmer test score, which would range from normal tear production to the most severe aqueous deficiency, which is less than 2 mm. Again, the problem is that the DEWS scale doesn’t weight any of these. There is no composite score, so it’s really a gestalt. I use the scale to grade clinical severity, and if the patient has any of the criteria for grade 3 or 4, that’s how I would grade it. It doesn’t have to be all of them, but they do usually go together.”

He adds that he doesn’t like the grading systems, but his preference is for the one from the first DEWS study. “It combines signs and symptoms. However, it could be flawed because we don’t know how to weight the signs and symptoms,” Dr. Pflugfelder explains. “Some of the dry-eye patients we see objectively don’t look like they have severe dry eye. Rapid tear breakup time may be the only sign, but their symptoms could be off the charts. Other patients who have severe autoimmune dry eye, like Sjögren’s syndrome, may have very minimal symptoms, but their corneas look horrible and they can’t see well. Right now, I’m just not aware of anything that would distinguish between those groups, but the DEWS at least includes both. I’ve been using a stepwise grading scheme from 1 to 4 if either the symptoms or the signs are bad.”

Dr. Rapuano adds that classifying dry eye is important both for determining treatment and for following patients after they’ve begun treatment. “I’ll usually call it mild, moderate, severe, or very severe,” he says. “As it gets more severe, I’m much more aggressive with my treatment. The more severe the dry eye is, the more frequently I’m following them, and I’ll increase the regimen more quickly."

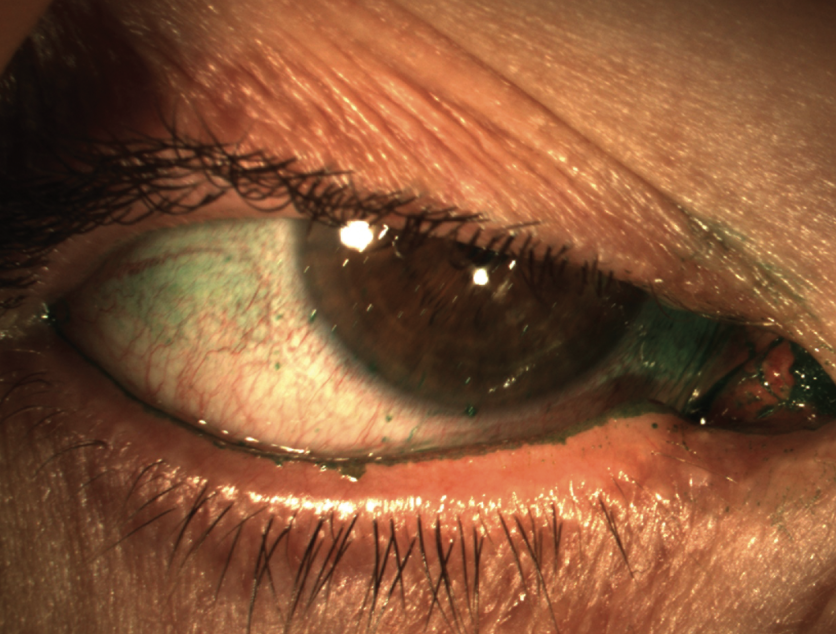

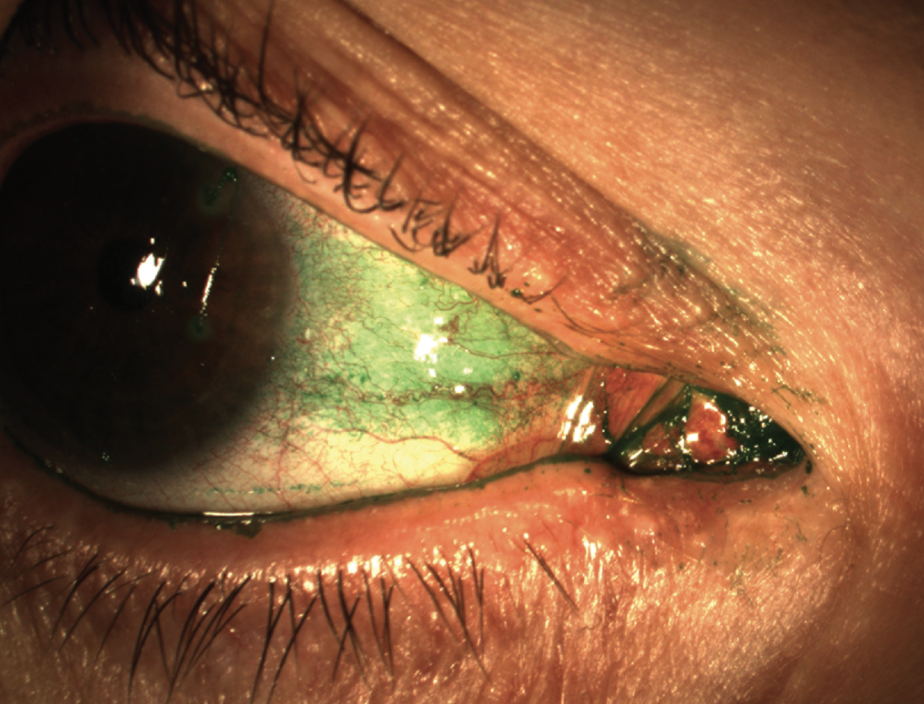

|

| Figure 3. Severe fluorescein staining over the inferior half of the cornea in a patient with moderate to severe dry eye. (Courtesy Christopher J. Rapuano, MD) |

He explains that mild dry-eye patients may be seen every three to six months, while severe patients may be seen every few weeks to a month. “If it’s mild, we start a regimen with the plan to see the patient in six months. We tell him or her to come in sooner if it’s getting worse,” Dr. Rapuano says. “Whereas, if it’s a pretty severe patient, I might see him or her in a month, or if it’s a super severe patient, I might see him or her in a week or two just to make sure there’s not any corneal erosion. For the vast majority of patients, it’s one to three months, and the three-month time period is because some of our treatments, such as Restasis or Xiidra, are getting reasonably good results by the three-month time period, so if I’m starting a patient on one of those, I often want to give the full three-month course to see whether that treatment is working or not.”

Dr. Pflugfelder says you don’t need to be overwhelmed with tests to be effective. “Ophthalmologists would be doing a great job to have a symptom questionnaire and then just follow a standardized protocol for staining the cornea and the conjunctiva, looking at the meibomian glands, and assessing tear production or volume,” Dr. Pflugfelder says. “If they’re doing that, they’re doing a great job, and with those components, they can definitely grade the severity and classify it as meibomian gland disease or aqueous deficiency. If a physician is going to make dry eye a large part of his or her practice, he or she should probably develop a standardized protocol for diagnosis and grading.”

DEWS II Recommendations

The Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society (TFOS) Dry Eye Workshop (DEWS) II Diagnostic Methodology Subcommittee has recommended the following order and clinical practice procedural guidelines: 2

Regarding symptoms, a positive result is a DEQ-5 score of 6 or above or an OSDI score of 13 or higher.

Regarding signs, the first step is to assess tear breakup time. According to DEWS II, three measurements should be taken, with the median value recorded. For diagnostic purposes, choose the lower median breakup value of the two eyes. The cut-off for a positive finding can be as low as 2.7 seconds for automated algorithms and up to 10 seconds for subjective observation techniques.

When non-invasive techniques cannot be used, fluorescein tear breakup time can be considered. However, because it’s more invasive, osmolarity measurement should be performed first. For fluorescein tear breakup time, fluorescein should be instilled at the outer canthus to avoid ocular surface damage. For optimal results, view the eye one to three minutes after instillation. A positive finding is a breakup time less than 10 seconds. The following tips can be helpful:

• Osmolarity should be assessed with a temperature-stabilized, calibration-checked device. A positive result is 308 mOsm/L or more in either eye or an interocular difference of more than 8 mOsm/L.

• Lissamine green staining is performed to assess conjunctival and lid margin damage. Observation should occur between one and four minutes after instillation. Observation through a red filter potentially aids visualization. A positive score is more than nine conjunctival spots.

• Fluorescein staining is performed to assess corneal damage. Optimal viewing time is between one and three minutes after instillation, and a positive result is more than five corneal spots.

• Lid wiper epitheliopathy can be observed stained with fluorescein, rose bengal or lissamine green dyes, although there seems to be a preference for just lissamine green in recent research, with viewing recommended three to six minutes after repeat instillation using two separate strips wet with two saline drops. A positive result indicates lid wiper epitheliopathy of 2 mm or more in length and/or 25 percent or more sagittal width (excluding Marx’s line).

• Dry eye severity can vary according to the time of day, so this should be considered when interpreting results and for monitoring dry-eye disease over time.

The Future of Dry Eye

Dr. Pflugfelder says that the incidence of dry eye is on the rise. “I could see dry-eye patients 10 hours every day,” he says. “Part of it is our lifestyle and climate change. Many people work on a computer at least eight hours a day in an air-conditioned environment. There are occupational, environmental, and probably nutritional factors that are contributing to its increased prevalence. We also have an aging population.”

Dr. Rapuano agrees. “With the warming of the world, global climate change may be part of that,” he says. “Masking for the past three years was also a part of that. The air would just kind of blow up in people’s faces from the mask.”

Drs. Pflugfelder and Rapuano have no financial interests to disclose.

1. Amparo F, Schaumberg DA, Dana R. Comparison of two questionnaires for dry eye symptom assessment: The Ocular Surface Disease Index and the Symptom Assessment in dry eye. Ophthalmology 2015;122:7:1498-1503.

2. Wolffsohn JS, Arita R, Chalmers R, et al. TFOS DEWS II diagnostic methodology report. The Ocular Surface 2017;15:3:539-574.