The Femtosecond Mystique

The Femtosecond Mystique To start off, it helps to have an idea of the costs physicians or ambulatory surgery centers will be dealing with when they get involved with femtosecond lasers for cataract surgery. They are considerable. Surgeons who are actively researching the lasers say they will probably cost between $400,000 and $500,000. There will also be a usage fee that will come in between $150 and $400 per eye, similar to the click fee associated with excimer lasers, as well as maintenance contracts that will cost between $25,000 and $50,000 per year, starting after the laser’s initial warranty period has expired. There will also be a relatively small cost for disposables used during each procedure.

However, physicians say that even though the femtosecond lasers for cat-aract surgery will be expensive, they sense that a sea change is under way in cataract surgery and it will be better to swim with the current than against it.

“The public is going to demand this,” says Lexington, Ky., surgeon Lance Ferguson, MD, who constantly studies efficiency and costs in his ASC and is currently working out how a femtosecond cataract laser might fit in. “When I got my femtosecond laser for LASIK, I got it mainly to cut a thin flap safely, because I had noticed that our complication rates were greater in patients with high K readings when we attempted to cut 160-micron flaps. So, we got the laser for people who didn’t want PRK but didn’t have enough tissue for a standard Hansatome. We figured that about 8 to 10 percent of our patient population would ultimately require it—but now 60 to 70 percent of LASIK patients actually come in demanding it. Even when we tell them that their corneas are 600 microns thick and will only be getting a 25-micron ablation and they won’t be ectatic even if there are problems with the formation of the flap, they simply say, ‘I want the laser.’ You’re kidding yourself if you don’t think that the public’s belief in the precision of the laser will be strong, even though all the usual surgical issues will remain. Like electronic medical records, it’s going to happen. You can get on it now and work out the kinks on your own schedule, or you can get slammed later.

“Also, when this technology becomes commonplace and the hospitals have them, it’s going to become a table leveler for the less-skilled surgeon, since these things do beautiful incision work,” Dr. Ferguson adds. “For those surgeons who may have struggled with surgical skills, it’s going to be a game changer, because the surgeons who were always the most skilled suddenly won’t stand out because of that skill anymore.” However, Dr. Ferguson is quick to add that, just like femtosecond lasers for LASIK, these devices will cause some complications. “Though it will make a lot of the cataract steps automated, you have to be careful not to let your own surgical skills erode, because you may need them in the event of an irregularity or a complication,” he says.

“Also, when this technology becomes commonplace and the hospitals have them, it’s going to become a table leveler for the less-skilled surgeon, since these things do beautiful incision work,” Dr. Ferguson adds. “For those surgeons who may have struggled with surgical skills, it’s going to be a game changer, because the surgeons who were always the most skilled suddenly won’t stand out because of that skill anymore.” However, Dr. Ferguson is quick to add that, just like femtosecond lasers for LASIK, these devices will cause some complications. “Though it will make a lot of the cataract steps automated, you have to be careful not to let your own surgical skills erode, because you may need them in the event of an irregularity or a complication,” he says.

Santa Barbara, Calif., surgeon Douglas Katsev, MD, who has given lectures for Alcon/LenSx, also thinks there will be push-pull forces at work from industry and patients. “I think it will get really good acceptance in the big cities, for sure,” he says. “And surgi-centers will buy a femtosecond cataract laser to get people to come to their center. If you own a surgi-center, the more cases that are done there, the more you make. Ophthalmologists will say I want this thing but I’ll also offer it at a center to grab other doctors who are just in solo practice, because patients may come in asking for it and be disappointed that those solo doctors don’t have it. Doctors will feel that they have to have that exposure. The other surgery center owners are going to want to have surgeons come into their center to use the laser for their cases because they’ll be able to generate revenue off of them; they’ll be willing to put out the cost of the laser to make money over time.”

Shadows of Doubt

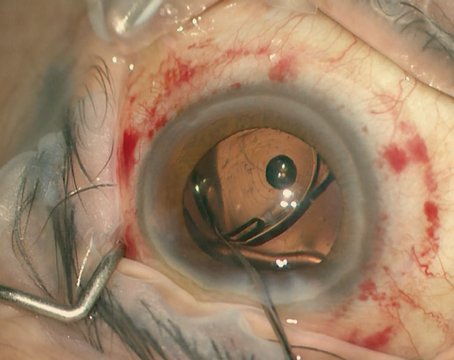

After the capital expenditure and recurring costs, the other challenge surgeons face is how to position the laser in their practices and how to bill for it. William Rich III, MD, the American Academy of Ophthalmology’s medical director of health care policy, doesn’t see easy answers to these questions. “The femtosecond laser is a wonderful piece of technology,” he says. “It enables surgeons to make more accurate capsulorhexes. The issue, however, is more of a regulatory/legal one. The Medicare code for cataract surgery is very generic. There’s one CPT code that covers 99 percent of cataracts. It says that you can make a tiny incision, open the eye up, perform a capsulorhexis with a 60-cent needle or a $100,000 machine, and then do phaco or extracap, and it doesn’t make any difference—you get paid the same. So from a surgeon’s perspective, the payment is the same and the payment to the facility is the same. I have an ambulatory surgery center that I am part-owner of, and any physician who comes in and uses a Fugo blade for one aspect of surgery and a femtosecond laser to the enter the eye, he’ll never be able to do cataract surgery at my center because I’ll lose a fortune on every case. There’s no differential in payment to the physician or the facility whether you make the corneal incision or the capsulorhexis with the femtosecond laser.

“The one application in cataract surgery I see for the femtosecond laser is the completely refractive cataract procedure,” Dr. Rich continues. “If you have a totally refractive cataract procedure in someone who doesn’t have a clinically significant cataract, is nearsighted and isn’t a candidate for LASIK, you can charge whatever you want because it’s not a covered service to insurance. So, the facility can charge whatever it wants and the surgeon can charge whatever he wants. It’s a negotiated payment between the patient and the facility, like a cosmetic brow lift.”

|

Though there may be issues with the mechanics of billing for the laser, surgeons who are poised to move into laser-assisted cataract surgery say there are different approaches that may help make the move successful.

• Bundled discounts. As long as it’s handled in such a way so as not to be an inducement, a company such as Alcon, which owns the LenSx femto-cataract laser and offers several lines of surgical equipment and intraocular lenses, could offer a better overall price if a surgeon purchased Alcon’s other instruments and devices, too. “Alcon and LenSx have the machine and they’re the leaders in the cataract market and want to stay that way. They’ll figure out a way to make the overall price work for the physicians but tie them to their equipment, lenses, phaco machines and viscoelastics,” says Dr. Katsev. “When you put it all together it will be reasonable.”

• Safety in numbers. With the cost of entry being high, surgeons say the average surgeon who wants to get into femtosecond cataract surgery should probably find like-minded colleagues. “If I were a mid-level practitioner who did maybe six cases per week, 200 to 300 cases per year, and I wanted to be a part of this, I’d probably take the time and develop an LLC and develop a center like we did for excimers,” says Dr. Ferguson. “I’d look around my area and get a group of surgeons together and approach one of the local ASCs or hospitals, preferably one that handles a lot of ophthalmic cases, and say, ‘We’ll promise you x amount of cases per month, but we want access to this technology.’ If the hospital buys this piece of equipment, it’ll need to charge the physician a per-use fee for the use of it, rather than the patient. The surgeon will need to increase his professional fee to cover that cost.”

• Going it alone. In certain, infrequent cases, a surgeon may be busy enough that he can buy his own femtosecond cataract laser. He would assume all the risk of the purchase, surgeons say, but as such he would collect all of the revenue, too. “If the private practitioner could actually afford it, I wouldn’t have it as part of the ASC at all,” says Dr. Ferguson. “Instead, I’d have it as a pre-treatment station in my laser suite, outside the ASC. I could then keep the instrument available in the office for other refractive uses, such as limbal relaxing incisions, and I wouldn’t have to go through the regulatory scrutiny that every instrument used in an ASC has to. In a similar way, a group practice could buy it and keep it in the office, pre-treating its cataract patients and then having them go to the hospital for surgery.”

But How Do You Charge for It?

Surgeons have several ideas for gaining access to femtosecond cataract lasers when they’re eventually on the market, but, harking back to Dr. Rich’s admonition about what Medicare will and won’t pay for, physicians are still unsure about all the instances in which they’ll be able to charge for the use of the device, and how they’ll do it. Here is the latest thinking.

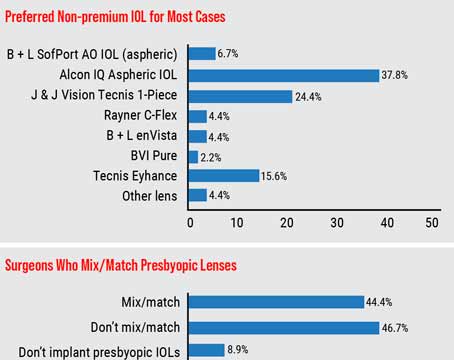

Many surgeons think the patients who will want their surgery performed with the aid of the femtosecond will be the ones who are also getting some sort of premium IOL. “It will, of course, depend on the volume of your practice,” says Eugene, Ore., surgeon Mark Packer, who consults for femtosecond maker LensAR. “Thirty percent of my patients opt for a presbyopia-correcting implant, either accommodative or multifocal, so that’s my group, the ones who would presumably pay a little more to have their surgical results improved by the use of the femtosecond. I’m not sure I’m going to give them the option of having the femtosecond with their premium lens; instead, I’ll just do it for all of them and increase my price. I don’t very much like the model of giving the patient a menu and letting him choose, because he doesn’t really have a good basis for making that choice. It comes down to the idea that I’m the doctor and I know what’s best for him.

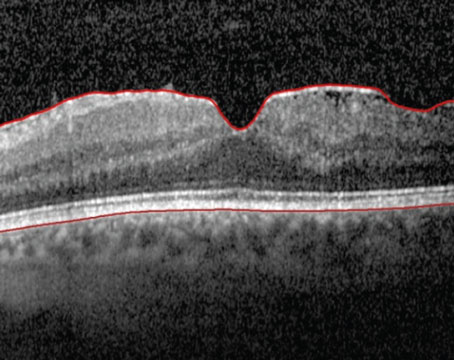

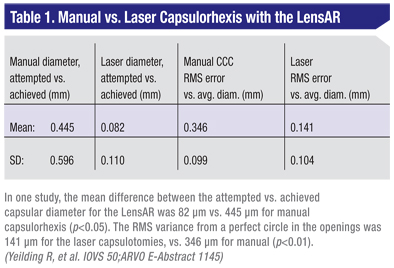

“If the per procedure fee were $500 per case,” Dr. Packer continues, “we might increase the cost of premium IOL implantation by maybe $1,000 because of the increased time it takes to do it with the laser and the capital expenditure that needs to be financed. I will do this because I believe in the science behind it. It’s better. It’s going to give more consistent, safer results and more assured outcomes.” (An example of a laser’s consistency in creating capsulorhexes appears in Table 1.) Dr. Ferguson envisions a similar scenario, but says pricing may be getting too high for premium lens patients to add another $1,000 to their bill—or whatever the charge for the use of the laser turns out to be. “There will be the monofocal or maybe monovision patient who’s not receiving an accommodative or multifocal lens but who is willing to pay the full laser fee for having the extra accuracy of the laser,” he says. “But I think the up-charge for patients already spending the money for an accommodative or specialty lens is getting so high already that you’ll have to do a combined fee for both the specialty lens and the femtosecond surgery in which you won’t add your usual full laser fee in for them. Instead, you can charge a fraction of it and add it to the price they’re paying for the premium lens.”

Surgeons hope they can make the case that the laser’s increased accuracy and safety, as well as the fact that Medicare already allows patients to pay extra for the increased quality of premium IOLs, will let them charge patients extra for the use of the laser for parts of the cataract surgery, not just refractive limbal relaxing incisions. “Right now, the rules are that CPT code 66984 is cataract extraction by any means, whether it’s a $500,000 laser or an 89-cent hook,” says Dr. Packer. “But we know the results are going to be different between those two approaches. And they may be different enough that payors can be convinced that it’s worth allowing patients who wish to pay more for those services to do so. Medicare used to not care if you were putting in a monofocal or a multifocal or an accommodating lens, but we changed that. We showed them the outcomes were better and that the premium lenses changed patients’ need for glasses and their quality of life.”

Dr. Ferguson says that even though it’s not 100-percent certain by any means at this point, a surgeon may be able to cover himself by having the patient sign an Advance Beneficiary Notice acknowledging that the laser aspects of the surgery aren’t covered by Medicare and that he’ll need to pay for them. He says the surgeon may also have to reimburse the patient some money since Medicare already paid for those aspects of the surgery that the surgeon did with the laser, similar to how surgeons have to give back some reimbursement when they bill extra for the use of a premium IOL.

The AAO’s Dr. Rich, however, says a premium lens is a different animal than a femtosecond laser, and that the steps of the surgery that the laser performs can’t be billed to the patient because Medicare already reimburses for them. “If you go in and implant a Crystalens or another premium IOL, the only covered benefit is the extra counseling and guaranteed LASIK if you need touch-ups afterward, et cetera,” he says. “But the cataract extraction itself and the facility fee for the cataract extraction are covered benefits, so that’s where you can’t bill. I was actually involved with this decision when it was made, and the head of CMS at the time made it very clear that it’s only the extra cost of the lens, the counseling and the planning that is billable as extra; but the facility fee—the surgery itself—is already covered by Medicare.”

What About the IntraLase?

While the impending introduction of femtosecond cataract lasers has surgeons scrambling to figure out how to make a new $500,000 investment feasible amid Medicare’s billing restrictions, there is another group of surgeons who make up the largest installed base of femtosecond lasers in the United States: IntraLase owners. These surgeons have either paid off their lasers or are close to paying them off, and also have the luxury of being able to use them for additional procedures other than just cataract, such as LASIK, astigmatic keratotomies and corneal procedures, so they don’t have to obsess over recouping their investment purely from cataract operations that they may or may not be able to bill for. If you were in this group, would it pay to wait for an upgrade to your IntraLase? The ultimate answer is still unclear, though Abbott Medical Optics is extremely motivated to get the IntraLase FS laser cataract-worthy.

Leonard Borrmann, AMO’s director of research and development, says the need to get a cataract-ready IntraLase to market “drives a sense of urgency” from his perspective. “It fits with the other piece of our business, the phacoemulsification business where we’ve been a leader in both fluidics and energy delivery,” he says.

In terms of how AMO will move into femtosecond cataract, Mr. Borrmann sees it as an upgrade. “Based upon the input from our customers, we have to focus on an upgrade or modification of the femtosecond IFS platform to adapt it to go beyond just flaps,” he says.

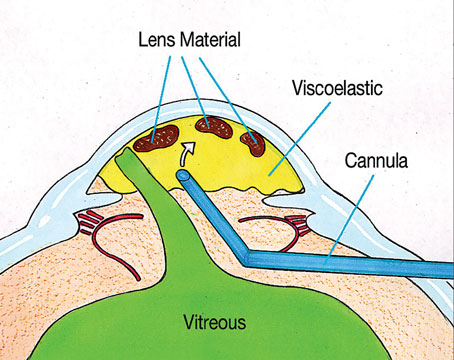

“The number-one area in which the IFS can have an impact is to provide for all the corneal incision needs of cataract and refractive surgeons. That would include clear corneal incisions and others. The second part is the delivery of a precise capsulorhexis.”

At this point, surgeons say time is of the essence for IntraLase, because once the femtosecond cataract lasers hit the market en masse and the patient buzz starts, surgeons who can perform laser cataract surgery early on will establish strong footholds.

Mr. Borrmann doesn’t give an exact plan for the IntraLase modifications, however. “We’re currently in active development,” he says.

Even though billing issues remain, and it will take a financial commitment, surgeons say the market forces may ultimately be too strong not to get involved with laser cataract surgery. “I think the cataract patients who have the laser will be less than half of our volume at first,” muses Dr. Katsev. “But it will eventually become close to 100 percent. And as we get our machines paid for, the price for the patient may come down because we’ll only be paying for the click fee. Then, almost every patient is going to have it. I don’t know how quickly it will happen, but I think it will become the standard of care.”