By most accounts, it’s one of the most common and trusted procedures in ophthalmology, with a long track record. Cataract surgeons have banked on its efficacy and reliability for decades.

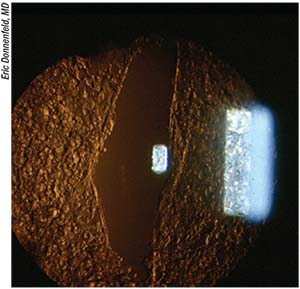

So why are some experts rethinking the risk/benefit ratio of Neodymium:YAG (Nd:YAG) laser capsulotomy for posterior capsule opacification after phacoemulsification and intraocular lens implantation? Controversy swirls around old vs. new data, long-term side effects, and the true rate of retinal and other complications. Here, surgeons weigh in on the topic.

Old Data vs. New Techniques

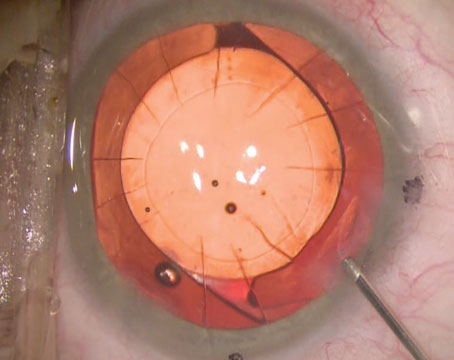

The risk of causing retinal detachment is the first factor cataract surgeons cite when

|

| Polishing techniques, chemical treatments and other types of lasers have been tried in the war against PCO. |

debating the need for a posterior capsulotomy. And even though the conventionally accepted incidence of 1 to 2 percent is low, the reality may be much lower, according to research1 conducted by Christopher Rudnisky, MD, a professor at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada.

Dr. Rudnisky evaluated the incidence of RD from an administrative dataset of patients from all age groups who received foldable implants with square edges and were followed-up at 90,120 and 150 days, and then six months and one year post-Nd:YAG capsulotomy. Some were followed out to 10 years (2003 to 2013). He found the conventionally cited 1 to 2 percent RD rate “overstates the truth ... the rate is substantially lower, between 0.5 and 1 percent.”1

The incidence of retinal detachment was 0.87 percent at five months post Nd:YAG; the rate of retinal tears after Nd:YAG capsulotomy at five months was 0.29 percent. The findings suggest that RD risk is highest in the first five months post-procedure. Dr. Rudnisky says that when RD occurs two years post-Nd:YAG it would be hard to prove the YAG caused it.

Older surgical and YAG capsulotomy techniques and older implant technology may account for the discrepancy between “what the text- books and literature said and what we saw in practice. I tell patients the risk is about one in 200 or 0.5%,” he says. “Even though our paper shows that the incidence of retinal detachment is lower than what we thought, it’s still not zero. It’s a life-changing event for the patient who develops one.”

Michael Snyder, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of Cincinnati, is somewhat skeptical that the YAG causes most RDs after capsulotomy. “Rather, coincidence with the natural history of retinal detachment plays a bigger role than stresses induced at the time of capsulotomy,” he says. Dr. Snyder acknowledges that the YAG procedure is “a cost and an inconvenience, and access to care can be a problem in some rural communities, but it remains a good solution.”

Many surgeons agree the 1 to 2 percent RD rate following Nd:YAG capsulotomy may not be representative of today’s clinical practice. Among them is Eric Donnenfeld, MD, clinical professor of ophthalmology at New York University. “This ra

|

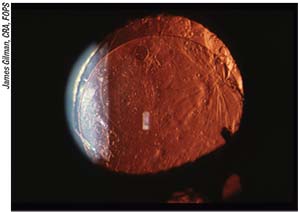

| Surgeons say to hold off on a posterior YAG capsulotomy for about three months postop just in case a lens exchange is warranted. |

te is often questioned as being too high,” he notes. However, some sub-populations are at more risk—specifically men with high myopia in their 50s and early 60s, says Douglas Koch, MD, professor and chair at the Cullen Eye Institute, Baylor College of Medicine in Dallas. “Their incidence of retinal tears/detachments just after cataract surgery alone could be 5 percent or higher, and that rate probably increases after posterior capsulotomy,” he says.

The Incidence of PCO

Although today’s technologies and techniques appear to have decreased the incidence of PCO, they may only have delayed its onset. The prevention of PCO through IOL design, and the elimination of proliferating lens epithelial cells with various capsule polishing techniques, chemicals and lasers has been attempted for decades. But “the bottom line is we haven’t achieved anything that approaches a good way to eliminate PCO,” Dr. Koch says.

Opinions also differ as to the actual incidence of PCO over time. Most surgeons agree, however, that early or later onset is correlated with IOL type, length of follow-up, and whether the cataract surgery was performed in a developing country. “The percentage of patients who get PCO is highly variable and dependent on the type of IOL implanted, surgical technique, cleaning of cortical material, and care in removing lens epithelial cells from the anterior capsule,” notes Dr. Snyder. In his practice, long-term PCO development is under 20 percent. “But it depends on how long patients live—eventually they all might develop PCO,” he says. “At two years, that rate is low single digits.”

Dr. Koch puts the rate of PCO development at

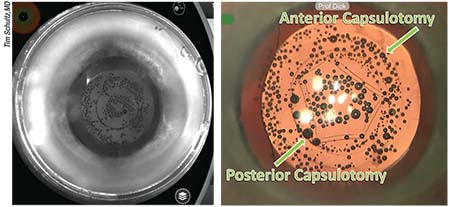

|

| Left: View through the infrared camera of the femtosecond laser during primary posterior laser capsulotomy. The treatment is performed at the end of surgery, after IOL implantation. Right: Immediately after the treatment, the posterior capsule starts to curl up. |

five to seven years postop at “probably 75 percent, even with contemporary square-edged IOLs. I tell my patients most will get this between two and four years postop.”

So, despite initial low PCO rates reported at three years postop with high-quality hydrophobic acrylic IOLs with true sharp edges and slim haptic-optic junctions, “PCO rates at five and eight years may still increase sharply,” according to Rupert Menapace, MD, PhD, FEBO, a professor at the Medical University of Vienna. He notes this delayed “barrier failure” is caused by Soemmering´s ring formation. Dr. Menapace says the reality may be even bleaker for patients in the developing parts of the world where “cheap one-piece hydrophilic IOLs with broader haptic-optic junctions are often used.” His evaluation of two hydrophilic, small-incision IOLs showed early and high PCO rates resulting in YAG laser rates of up to 49 percent.2

More Complications

Not all ophthalmologists agree on YAG laser capsulotomy’s overall safety record. “The incidence of retinal detachment is reported to be 0.6 to 2.5 percent and 0.1 to 3.6 percent for cystoid macular edema,” Dr. Menapace notes.3

The sheer number of patients undergoing the procedure makes an assumed 1 percent retinal detachment rate not insignificant: “If you’re in that 1 percent, you will probably not consider it safe,” says H. Burkhard Dick, MD, PhD, director and chairman of the department of ophthalmology at the University of Bochum Eye Hospital in Bochum, Germany.

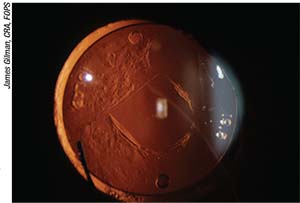

Neodymium:YAG laser capsulotomy almost always disrupts the anterior vitreous face, and the capsulotomy itself increases the complexity and the risks of an IOL exchange, surgeons say. “Retinal surgical outcomes are rarely clear cut ... high myopes may have more problematic retinal detachments, including giant retinal tears--these rates are still low, but [the problem] is not trivial,” Dr. Koch notes.

Late consequences after the procedure don’t end with retinal detachments: Epiretinal gliosis, macular edema and damaged IOLs are also seen. Another, less-well-known problem is possible in patients with trabeculectomies. A recent study postulates that Nd:YAG laser capsulotomy may have a negative impact on the filtering bleb, causing subsequent loss of IOP control.4 The researchers recommend caution when using the Nd:YAG in eyes that have undergone filtering surgery.

In the first few days following laser capsulotomy many patients note increased floaters, which eventually become less noticeable. In a small percentage of frustrated patients, however, the floaters persist. Dr. Koch describes a typical scenario: “Patients recover vision after cataract surgery, then lose vision due to PCO, have a YAG, and then develop a new set of problematic visual symptoms.”

There are additional aspects that some surgeons find even more controversial than RD and floaters. “Many patients present with bilateral PCO,” says Dr. Menapace. “Typically, one eye has severe PCO and the second eye has clinically disturbing PCO. Though many patients don’t realize when PCO develops in one eye, unilateral PCO actually reduces binocularity and stereopsis, which could be a factor for the increased incidence of falling and fractures.”

Finally, the financial burden is significant. At $1.1 billion annually, cataract surgery with IOL tops Medicare payments for ambulatory surgery procedures; complex cataract surgery comes in at number five ($96 million); and YAG capsulotomy’s $65 million cost puts the procedure at number 10, according to Becker’s ASC Review.5

Is PCO Prevention Possible?

Most experts agree that meticulous surgery is the first, best way to prevent PCO, but techniques differ. With standard in-the-bag IOL implantation, the best method to avoid PCO today, Dr. Menapace believes, is to create a “perfectly sized and centered anterior capsule opening which ensures a 0.25 to 0.5 mm circumferential overlap of the IOL optic.” He advises using IOLs that truly have sharp posterior edges and slim haptic-optic junctions. Dr. Menapace also recommends “thorough removal of cortical material from the capsular equator while keeping the anterior lens epithelial layer on the posterior side of the anterior capsular rim intact.”

Ophthalmic companies, researchers and clinicians have spent decades devising new technologies and techniques to eliminate PCO. Better cortical cleanup, square-edged IOLs and laser-generated capsulotomies have been touted as keys to preventing PCO.

Another technique, originally called Dodick phacolysis, was derived from Dr. Jack Dodick’s initial work in the 1990s, and uses Nd:YAG laser energy to emulsify the lens. The company behind the current technology is A.R.C. Laser of Nuremberg, Germany. In this approach, the emulsified material is aspirated out of the eye through the handpiece in a manner similar to phacoemulsification. The laser can also be used to remove the laminin layer of the posterior capsule, which can prevent posterior capsule opacification. The system is available in Europe and has just been FDA approved. The other new technology that may make a difference is the Zepto capsulotomy device. “The Zepto has been shown to reduce PCO,” Dr. Donnenfeld says. “It’s a nice way to make capsulotomies. The problem is that it’s not reimbursable, so that adds cost to the procedure. However, it’s become part of many surgeons’ premium cataract packages.”

Less high-tech, but still effective, Dr. Menapace explains, is a manual posterior capsulorhexis. He says the procedure is controlled and safe. “It can and should be learned by all cataract surgeons,” he declares. “It works with any IOL design and material, and should be a routine part of cataract surgery.” He says that manual posterior capsulorhexis can be performed on virtually all cataract cases. “Additional posterior entrapment of the optic into the posterior capsulorhexis opening completely eradicates PCO,” he says, citing an evaluation of 1,000 consecutive cases showing “excellent long-term efficacy and safety.”6 Some surgeons have pointed out the drawbacks of this technique: It’s technically more challenging than conventional cataract surgery, as it requires opening the posterior capsule, possibly inviting the vitreous to come forward. Also, if a lens removal or exchange is required later, an anterior vitrectomy will also be necessary.

Dr. Dick also thinks opening the posterior capsule at cataract surgery prevents PCO. He advocates a primary posterior laser capsulotomy using the femtosecond laser (he uses the Catalys Precision Laser System from J&J Vision) after IOL implantation. The laser targets the posterior capsule in front of Berger’s space, a tiny anatomical gap between the posterior capsule and the anterior hyaloid membrane. He says the femtosecond laser’s three-dimensional optical coherence tomography imaging functions permit the surgeon to survey the altered topography of the anterior segment immediately after surgery. Minutes after IOL implantation, Dr. Dick says this OCT scan “demonstrates that 70 percent of patients have a Berger’s space of sufficient depth to perform a safe PPLC .... This is a safe technique with consistent results and represents a solution to prevent PCO.”

Other ways to eliminate or retard PCO rely on mechanical or chemical methods to destroy LECs. Despite its initial appeal, however, total elimination of LECs may not be a panacea, warns Dr. Koch. Although rare, he says that “dead bag syndrome” can occur, in which there’s no secondary proliferation of lens epithelial cells. If this happens, the capsule becomes diaphanous and floppy, unable to support the IOL, and subsequently dislocates. “If, for some reason, you have to suture through the capsule, it falls apart,” Dr. Koch says.

Nick Mamalis, MD, professor of ophthalmology and director of ocular pathology at the University of Utah’s John Moran Eye Center in Salt Lake City, says “There are fairly good data that show polishing LECs decreases the ACO incidence, but does not lower the PCO rate [after aggressive anterior capsule polishing].” He says that one widely accepted reason is that the anterior and posterior capsule don’t fuse as rapidly, so migrating cells are more likely to get past the edge of a square-edged IOL before the fusion occurs.

The balance between overly aggressive and not enough capsule cleanup is a delicate one. But most surgeons agree that some residual LECs help fibrose the capsule and stabilize the IOL. “We try to determine how to control this amount ... so that we get just the right amount of capsule fibrosis to hold onto the lens, but not so much that PCO occurs,” says William Barlow Jr., MD, assistant professor at the Moran Eye Center.

Pediatric cases, which tend to have much more aggressive PCO, and cataract surgery in developing countries where access to the Nd:YAG laser is limited at best, are among the “most compelling reasons to eliminate YAG capsulotomy,” Dr. Barlow says.

Whether laser-assisted capsulorhexis is worth the expense and time continues to be debated, and proponents for the Zepto, femtosecond laser or manual continuous circular capsulorhexis cite both research and personal experience to support their individual preferences.8-12

To YAG or Not To YAG

Despite a relatively safe track record, timing and circumstances are critical factors when performing a YAG laser capsulotomy. Examples include dysphotopsias related to multifocal IOLs or lenses in general. “Unfortunately, often the surgeon’s first reaction is to YAG that patient,” says Dr. Mamalis. “There are a lot of potential risks involved. If you open the capsule, then an IOL exchange becomes more difficult to perform. I would very much recommend looking hard at the patient’s symptoms prior to considering a YAG laser.”

For example, the majority of negative dysphotopsias (a temporal hooding or darkening of vision) resolve in about three months, surgeons say. Patients with positive dysphotopsias (dazzling, disabling light) may not get better over time. “YAG laser does not improve this,” Dr. Mamalis notes.

He recommends holding off a minimum of three months before doing a YAG laser in patients with side effects such as blurry vision, glare and halos. “Unfortunately, in our tertiary care center we frequently see patient referrals after a YAG was performed for IOL-related symptoms, but we end up having to perform an IOL exchange, which can be very difficult due to the open bag,” Dr. Mamalis says. The exchanged lens may have to be sulcus fixated and, when the capsule is open, it’s difficult to remove the IOL without disturbing the vitreous. Surgeons note that these cases also have an increased incidence of cystoid macular edema.

Future Directions

If the future holds a truly accommodating IOL, what are the patient’s prospects for good vision post-YAG? That’s why the attention of some who are trying to eliminate PCO is focused on the design of new IOL technology.

Whether PCO itself can be prevented, thereby eliminating any YAG-capsulotomy-related problems, is debatable, surgeons say. Posterior, square-edged acrylic IOLs delay the onset of PCO, but despite the material or lens design, significant incidence of PCO eventually occurs. “We really need to look at different ways of retarding or preventing PCO,” Dr. Mamalis says.

Current research suggests a large, bulky IOL that totally fills the capsular bag will decrease PCO. “Power Vision’s IOL has large balloon-shaped haptics that are involved in the accommodating mechanism. In the rabbit model, when the lens fills the capsular bag completely, the development of PCO is delayed,” Dr. Mamalis explains.

So, why does this model work? One reason may be that an open capsular bag allows aqueous

|

| A YAG laser posterior capsulotomy won’t improve positive dysphotopsias. |

humor to circulate through part of the bag. Presumably, different substances in the aqueous may retard the opacification. Also, if the anterior and posterior bag edges are open and a broad haptic fills the capsular bag and precludes capsule contact, PCO might be prevented, surgeons say.

New research is focusing on ways to modulate the LECs so that they don’t fibrose and don’t cause capsule opacity, yet still keep the capsule elastic. At one time, Dr. Mamalis says, “people wanted to remove all LECs. Now we’re saying maybe there’s benefit to retaining some LECs to maintain the bag and keep it healthy.”

Preventing PCO will be of increased importance as new, accommodating IOLs that rely on intact posterior capsules become available. A truly accommodating IOL that changes its shape requires a flexible capsule, and in these cases, fibrosis/contraction becomes the bigger issue.

Dr. Donnenfeld says that he uses multifocals and extended-depth-of-focus intraocular lenses about 15 percent of the time. “But there are more glare and halos are associated with them compared to single-focus IOLs,” he says. “On the horizon are newer accommodating IOLs in trials that will reduce opacification by separating the anterior and posterior capsule leaflets.”

There are IOLs both in development and already in clinical trials that rest within the capsular bag and require continuous flexibility of the capsule to respond to ciliary body movement. The concern for capsule-fixated accommodating IOLs is that IOL movement in the capsule will diminish with LEC proliferation, reducing or possibly eliminating the accommodative IOL power change. “That said, there are accommodative IOLs showing good response up to two years postoperatively, but longer follow-up is needed,” Dr. Koch notes.

No matter what side of the PCO/YAG debate you’re on, it’s clear that unwanted side effects of YAG laser procedures in certain eyes, patients’ increasing demand for sharp vision postoperatively and the development of truly accommodating IOLs will play important roles in PCO management and avoidance in the future. REVIEW

None of the surgeons have a financial interest in the products that they discussed.

1. Wesolosky JD, Tennant M, Rudnisky CJ. Rate of retinal tear and detachment after neodymium:YAG capsulotomy. J Cataract Refract Surg 2017;43:923-928.

2. Schriefl SM, Leydolt C, Stifter E, Menapace R. Posterior capsular opacification and Nd:YAG capsulotomy rates with the iMics Y-60H and Micro AY intra-ocular lenses: 3-year results of a randomized clinical trial. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015;93:4:342-7.

3. Steinert R. Nd:YAG Laser Posterior Capsulotomy, AAO ONE Network. https://www.aao.org/current-insight/ndyag-laser-posterior-capsulotomy-3. Accessed 2 April 2018.

4. Diagourtas A, Petrou P, Georgalas I, et al. Bleb failure and intraocular pressure rise following Nd: Yag laser capsulotomy. BMC Ophthalmol 2017;17:1:18.

5.Becker’s ASC Review. https://www.beckersasc.com/asc-coding-billing-and-collections/medicare-payment-for-10-top-asc-procedures-by-case-volume.html. Accessed 2 April 2018.

6.Menapace R. Posterior capsulorhexis combined with optic buttonholing: An alternative to standard in-the-bag implantation of sharp-edged intraocular lenses? A critical analysis of 1,000 consecutive cases. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2008;246:6:787-801.

7. Gimbel HV, Neuhann T. Development, advantages, and methods of the continuous circular capsulorhexis technique. J Cataract Refract Surg 1990;16:1:31-7.

8. Chang D. Zepto precision pulse capsulotomy: A new automated and disposable capsulotomy technology. Indian J Ophthalmol 2017;65:12:1411–1414.

9. Ewe SY, Abell RG, Vote BJ. Femtosecond laser-assisted versus phacoemulsification for cataract extraction and intraocular lens implantation. Curr Opinion Ophthalmol 2018;29:1:54-60.

10. Mastropasqua L, Toto L, Calienno R, Mattei PA, Mastropasqua A, Vecchiarino L, Di Iorio D. Scanning electron microscopy evaluation of capsulorhexis in femtosecond laser–assisted cataract surgery. JCRS 2013;39:10:1581–1586.

11. Chang DF, Mamalis N, Werner L. Precision pulse capsulotomy: Preclinical safety and performance of a new capsulotomy technology. Ophthalmology 2016;123:2:255–264.