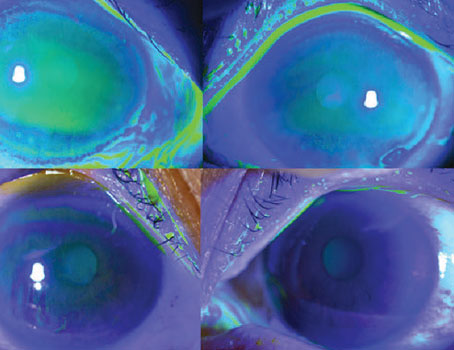

Delayed Re-epithelialization

In cases of epithelium-off cross-linking, which many surgeons currently use due to its effectiveness, one of the chief complications to be wary of is a delay in re-epithelialization, since this leaves the cornea open to other problems.

“The most common complication I’ve had is delayed re-epithelialization, occurring in 2 to 5 percent of cases,” says Singapore surgeon Jerry Tan. “The delay can go as long as two weeks. To avoid it, you have to get the epithelium to heal quickly. For this I use autologous serum and a bandage contact lens. I also keep the eye as moist as possible postop, which means lots of artificial tears.”

Miami surgeon William Trattler says he’s noticed risk factors for delayed healing. “They include very steep corneas, as well as patients with steep corneas in whom you place a bandage contact lens,” he says. “What can occur is the bandage lens can rub the apex of the cornea and prevent the epithelium from healing. In such cases, remove the contact lens and consider using a ProKera [corneal bandage device].”

When he performs an epi-off cross-linking procedure, Jodi Luchs, MD, co-director of refractive surgery for the North Shore/Long Island Jewish Health System, says he follows the patient very closely. “I like to see the patient every day or every other day,” he says. “And, if I find that the epithelium isn’t healing, I’m aggressive with the use of punctal plugs and preservative-free lubricants. I also use the minimum amount of medications that might retard re-epithelialization, such as steroids. I may also cut back on or eliminate the NSAID. You can include ointments along with a preservative-free lubrication, such as bacitracin antibiotic or various other over-the-counter lubricating ointments.” Surgeons also say changing the brand of bandage lens can help in some cases.

Close follow-up can also allow the surgeon to remedy the situation, based on what he sees in the exam. “In rare cases, epithelial cells will be heaped up at the edge of the epithelial defect and won’t migrate over,” says Toronto surgeon Raymond Stein, who was the first surgeon to perform corneal cross-linking in Canada eight years ago. “If we see that appearance, especially at seven days postop—where most cases would have healed in four or five days—we’ll often scrape the edge of the heaped-up epithelium to induce healing.”

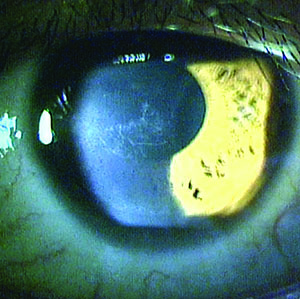

Corneal Haze

Surgeons say any time you debride the epithelium, introduce a chemical into the cornea and then bombard it with UV light, haze is a possibility, though they acknowledge that it’s less likely in epi-on procedures.

“Haze is very transient,” says Dr. Tan. “It starts at about three weeks after surgery, then increases a little for one to two months, and then by six months is almost completely gone. Also, it’s not more than 1+ haze, and is so mild many patients often don’t realize they have it.”

|

Surgeons say managing corneal haze after cross-linking is similar to dealing with post-PRK haze. “Treat it with a topical steroid such as FML or loteprednol, one drop four or six times per day until the recovery is evident,” says Dr. Alio. “Then, decrease the dose with time. The patient should also wear sunglasses whenever he’s outside, especially if he lives in a sunny region, because haze increases with sun exposure.”

Corneal scarring, which occurred in 2.8 percent of epi-off cross-linking patients in one prospective study, can be a result of dense haze.1 “If a scar is more peripheral, the patient can still have good vision,” says Dr. Luchs. “If the scar is causing some irregular astigmatism, which keratoconus patients have already, the patient may see well as long as the opacity isn’t in the center of vision. He can often get good vision with the use of a rigid contact lens or a scleral lens. However, if a scar is dense and large enough, and interferes with the line of sight, the surgeon’s only recourse may be a corneal transplant.”

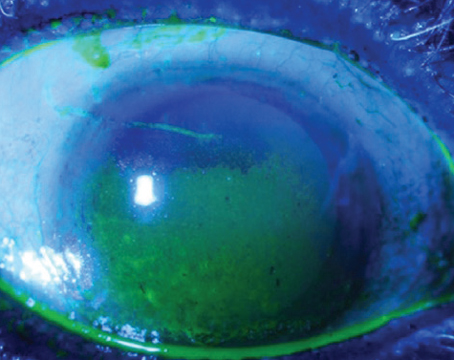

Inflammation

Surgeons say opening up the epithelium also leaves the eye vulnerable to sterile inflammatory infiltrates as well as the rare case of infection.

If a patient develops sterile infiltrates, a complication that occurred in 7.6 percent of eyes in one study,1 surgeons say they’ll increase the steroid dosage. If an entity is infectious, however, it naturally poses a greater diagnostic and management challenge. “Number one: Culture it,” says Dr. Luchs. “Often, most physicians will be able to tell the difference between an infection and a sterile infiltrate. But when in doubt, treat it as infectious. This involves increasing the antibiotics to every hour or every two hours depending on the clinical appearance and the cultures, and then proceed accordingly. Also, reduce your steroids.”

To help decrease the infection risk, Dr. Tan pretreats the eye for two days preop with antibiotics. “I use a combination of tobramycin and levofloxacin,” he explains. “I like to include tobramycin because it’s inexpensive and sometimes you’ll have a patient with a gram negative bacterial infection, which is susceptible to tobramycin. I believe infections with cross-linking develop after the operation. Usually, it’s because the patient hasn’t been following the postop regimen: He hasn’t been instilling the eye drops or his contact lens has become contaminated. Handling the contact lens and placing it in the eye postop must be done under sterile conditions.”

Corneal cross-linking can trigger a reactivation of herpes simplex virus, and some surgeons consider a history of HSV a contraindication to cross-linking.2 If you are going to proceed with cross-linking in a patient with a history of herpes, surgeons recommend antiviral prophylaxis preop and continuing into the postop period. If someone develops herpes simplex keratitis postop, treat it aggressively. “If you see herpes,” recommends Dr. Trattler, “the patient needs topical ganciclovir, Zirgan and/or oral Valtrex. My regimen for any herpes keratitis is Zirgan five times a day for a week to 10 days, and Valtrex 500 mg t.i.d.”

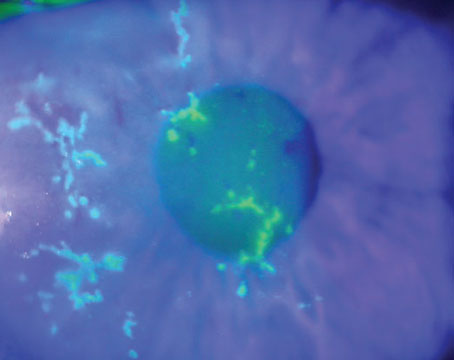

If you think you’re dealing with a case of herpes keratitis, stop and really scrutinize the eye, because it could be a notorious masquerader, the pseudodendrite. “A pseudodendrite is caused by an atypical healing response in which the epithelium from one side of the cornea meets the epithelium from the other side and creates the appearance of a herpes dendrite in the area where they meet,” says Dr. Stein.

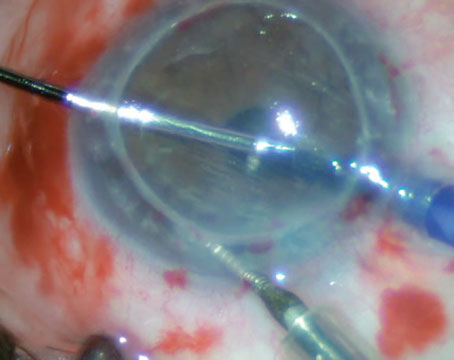

Endothelial Issues

To prevent the treatment from damaging the endothelium, surgeons say adherence to the cross-linking protocol is crucial, especially with regard to corneal thickness.

Dr. Stein says a patient with a thin cornea is a concern. “We know we need a cornea around 400-µm thick to be safe with corneal collagen cross-linking, since this prevents the UV light from damaging the corneal endothelium,” he says. “We’ve found that there are a variety of riboflavin drops that can induce swelling in the cornea. For patients with a clear cornea, even if their corneal thickness is as low as 320 µm, we can induce enough swelling with these drops to get their cornea above 400 µm to allow us to perform cross-linking safely. The drop is a hypotonic solution of riboflavin, and we have ours made up by a specialty pharmacy in Toronto. There are other drops that are available in Europe, and quite a few compounding pharmacies can make them.”

Dr. Stein says he’s seen patients have a stromal reaction postop that includes some edema, but hasn’t had any permanent corneal edema after cross-linking. “This would be a serious issue and, if it happened, you’d be concerned about damage to endothelial cells,” he avers. “But as long as we’ve been respecting the 400-µm minimum thickness, we haven’t seen it.”

In the rare instance that there does appear to be some endothelial damage, Dr. Luchs says all may not be lost. “Were it to happen, the first thing you want to do is simply wait,” he says. “The endothelium can recover after undamaged endothelium slides in and takes over the function in the area where the damaged endothelium had been present. You can often see some visual recovery over time after this happens; the endothelium could be damaged but not dead, and there could be potential for recovery. In general, you want to wait at least three months after the onset of the problem for endothelial recovery. If recovery doesn’t occur, then you have to consider some sort of transplantation procedure, whether it be DSAEK or, more likely since these corneas are usually already misshapen, a full-thickness transplant.”

Treatment Failure

Though it’s not a complication per se, an undesirable outcome of cross-linking would be for the patient’s corneal disease to continue to progress.

Dr. Stein says that, in his experience, most cases will remain stable. “In general, if the patient’s corneal steepness is 58 D or less, there’s a 98- to 99-percent chance that the cornea will be stable after cross-linking and won’t need an additional treatment,” he says. “We’ll wait six to 12 months before observing that, because it’s hard to tell if the cornea’s stabilizing on topography maps before six months. However, if we see progressive steepening after six months we’d become concerned and offer a second treatment.” Retreatments are performed exactly like the primary treatment, surgeons say.

Dr. Trattler says that a cornea in which keratoconus progresses after cross-linking isn’t exactly a failure, it just had a severe case of the disease. “When you do a cross-linking treatment, you make the cornea stronger,” he says. “So, if a cornea is exceptionally weak, and you then strengthen it by a certain amount, it still might not be strengthened enough to keep it from progressing. It’s kind of like a barrier in the road that may slow a car but not stop it. In that case, you might need two barriers. In cross-linking, a second treatment strengthens the cornea further. Hopefully, with a second treatment you get a stiff enough cornea that it doesn’t progress anymore. One key that we’ve learned is, if you want to reduce the chance of failure in a cross-linking patient, stress to him to not rub his eyes. Rubbing contributes to progression.”

Dr. Luchs says that, when the proper protocols are followed, corneal cross-linking is, on balance, a safe and effective procedure. “We have something on the order of 16 years of data demonstrating the efficacy of this procedure for keratoconus,” he says. “The upside of this procedure is high: Patients can lock down their disease in an early state before it progresses and prevent the need for a corneal transplant in their lifetime. And the downside risk is very small because of the low risk of complications, especially with epithelium-on but even with epi-off procedures. Patients have very little to lose, and everything to gain.” REVIEW

1. Koller T, Mrochen M, Seiler T. Complication and failure rates after corneal crosslinking. J Cataract Refract Surg 2009;35:8:1358-62.

2. Kymionis GD, Portaliou DM, Bouzoukis DI, et al. Herpetic keratitis with iritis after corneal crosslinking with riboflavin and ultraviolet A for keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg 2007;33:1982.