|

Though the most common culprits behind corneal ulcers are usually bacterial, atypical agents like fungi and protozoa can masquerade as a seemingly run-of-the-mill red eye and cause endless complications down the line if not brought to heel with the proper course of therapy.

Treating a corneal ulcer starts with correctly identifying the causative organism, and that involves a combination of approaches. Here, experts share diagnostic tips, and explain how and when to culture and which treatments you should reach for.

Narrowing Down Etiologies

“Corneal ulcers can present in very different forms and colors,” says Sophie Deng, MD, PhD, professor and Joan and Jerome Snyder Chair in Cornea Diseases at the Stein Eye Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles. “But looking at the cornea alone can be misleading. Textbooks will say that fungal infections have feathery edges, but we see this characteristic all the time in microbial infections as well. Using a combination of presentation, patient history and a consideration of the various risk factors will help to guide you.”

A thorough patient history that includes information about lifestyle, hygiene and occupation will often clue you in to the types of infections the eye is most susceptible to. “Risky behavior, recent trauma, a history of herpes in the eye, duration of symptoms, an abrupt or gradual onset, and prior therapy before seeking care are all important to ask about,” says Kathryn Colby, MD, a professor and chair of the department of ophthalmology at New York University.

Marjan Farid, MD, a clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of California Irvine, offers some examples. “An agricultural worker may be at greater risk for a fungal infection because of exposure to soil and plant material,” she explains. “A contact lens wearer who’s been sleeping in their contact lenses or has poor contact lens hygiene is at a higher risk for Pseudomonas corneal ulcers. And if they’ve gone into fresh water wearing their contact lenses or wash their contact lenses with water instead of contact lens solution, they’re at risk for Acanthamoeba infection.

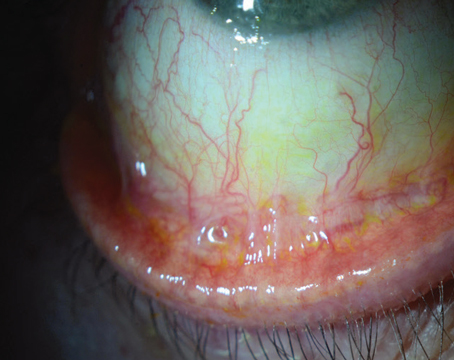

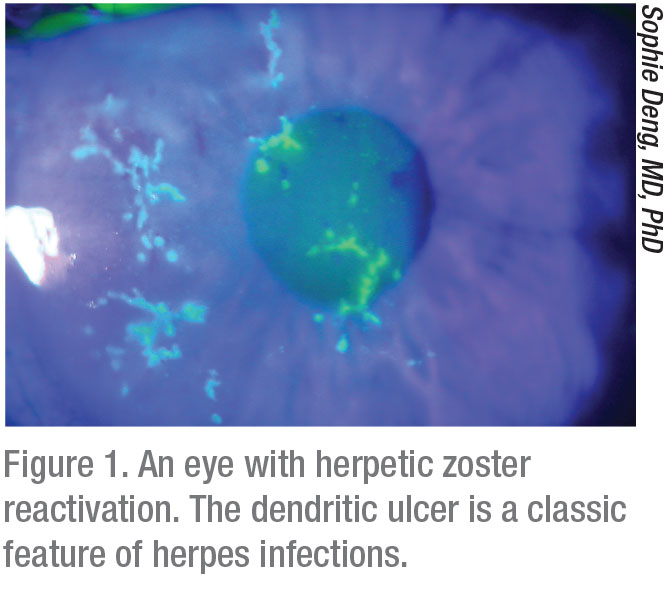

“Herpes-related keratitis is also very common in this country,” Dr. Farid continues. “A large percentage of the population has the herpes virus in their body. It manifests in times of stress, but herpetic outbreaks in the eye will manifest in only a small percentage of people. The outbreaks can be epithelial, stromal or endothelial. Epithelial keratitis is not uncommon and has a specific type of presentation—usually a dendritic pattern on the ocular surface (Figure 1). That pattern will clinch a diagnosis, but sometimes herpes can present more atypically. We always have to consider herpetic disease when we see epithelial ulcerations of the cornea.”

Dr. Colby adds that a history of present illness in addition to the medical history is also something to take under consideration. “Your patient may have coexisting diseases that could impact your diagnosis,” she says. “Do they have a history of diabetes or are they immunosuppressed for any reason? These types of patients will be at higher risk for almost any infection.”

Autoimmune diseases, when not well-controlled systemically, can cause significant inflammation of the blood vessels of the ocular surface. “The tear film may also be inflamed, and the patient may develop corneal melt, resulting in thinning of the cornea,” says Dr. Farid. “The patient may also develop secondary bacterial infections.”

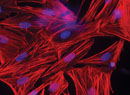

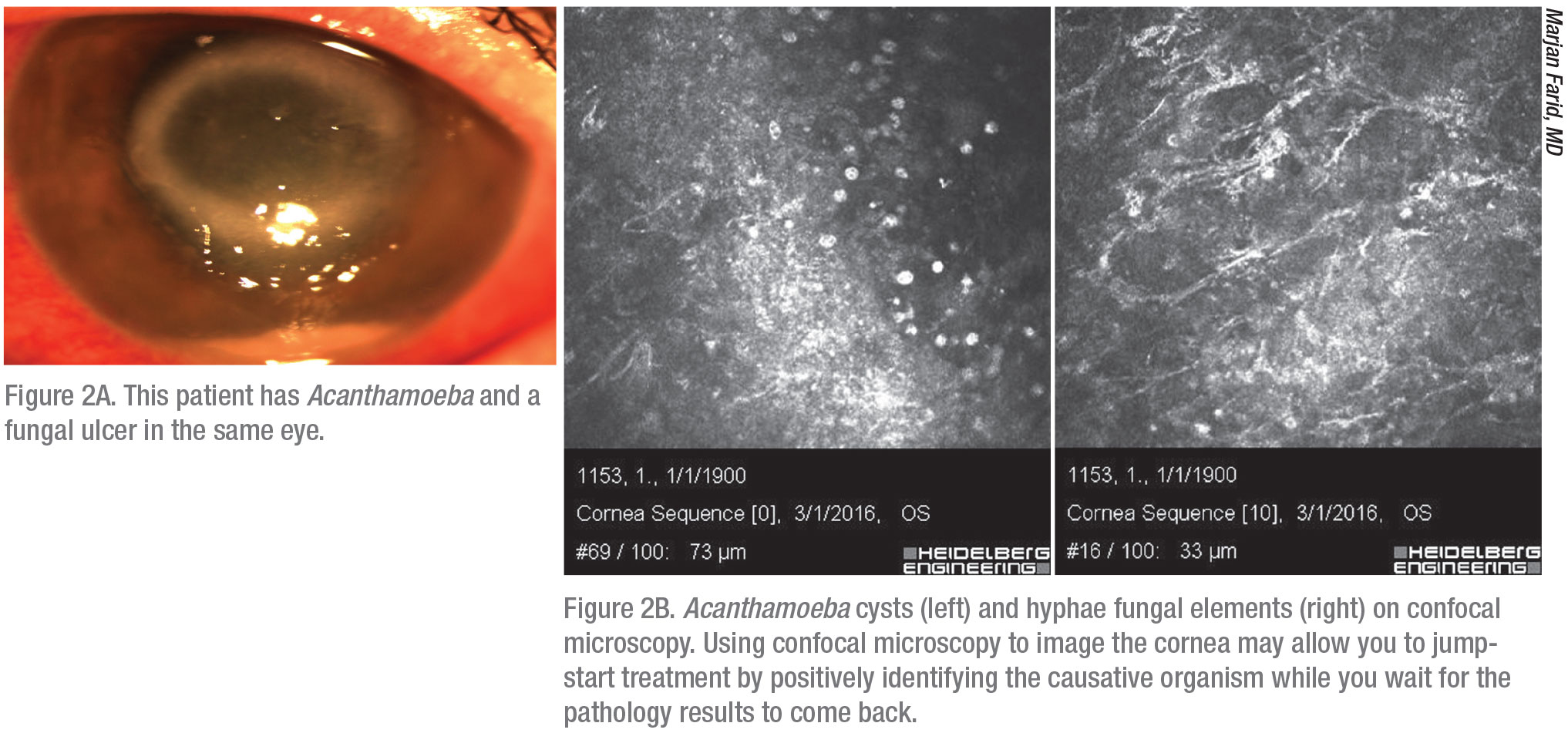

For suspected fungal infections and Acanthamoeba, confocal microscopy, if available, can help make the diagnosis (Figure 2). “Confocal microscopy enables us to see organisms in the different layers of the cornea,” Dr. Deng says. “Fungal and Acanthamoeba cultures take quite a bit of time to come back from the lab, but we can image the patient in the meantime to see whether a fungal infection can be ruled out.” She adds that sometimes imaging isn’t sensitive enough to detect the organism in its early stages, but the organism may show up on a second, later imaging.

|

“When In Doubt, Culture”

Dr. Colby notes that you need to do the cultures in a way that will provide you with the information you want.

You’ll want to culture large, central corneal ulcers, as well as large peripheral ulcers, she says. You may not need to culture smaller peripheral ulcers that are less vision-threatening and have a fairly clear history—for example, a contact lens wearer with redness and discomfort in one eye for a few days and a very small peripheral ulcer. “I usually start these patients on a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone broad-spectrum antibiotic and see them the next day,” Dr. Farid says. “If they’ve responded already, I know we’re on the right track. Those will usually clear within a few weeks without needing a culture, so those are the only times I don’t culture. Most other times, I’ll culture a corneal infection so we can get a diagnosis before we start the patient on therapy.”

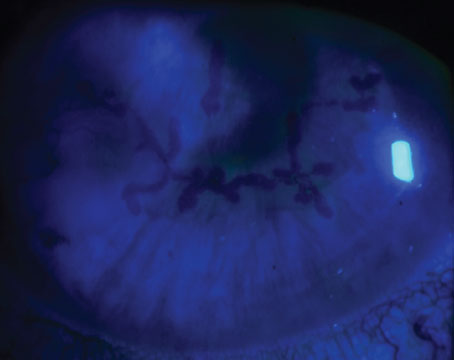

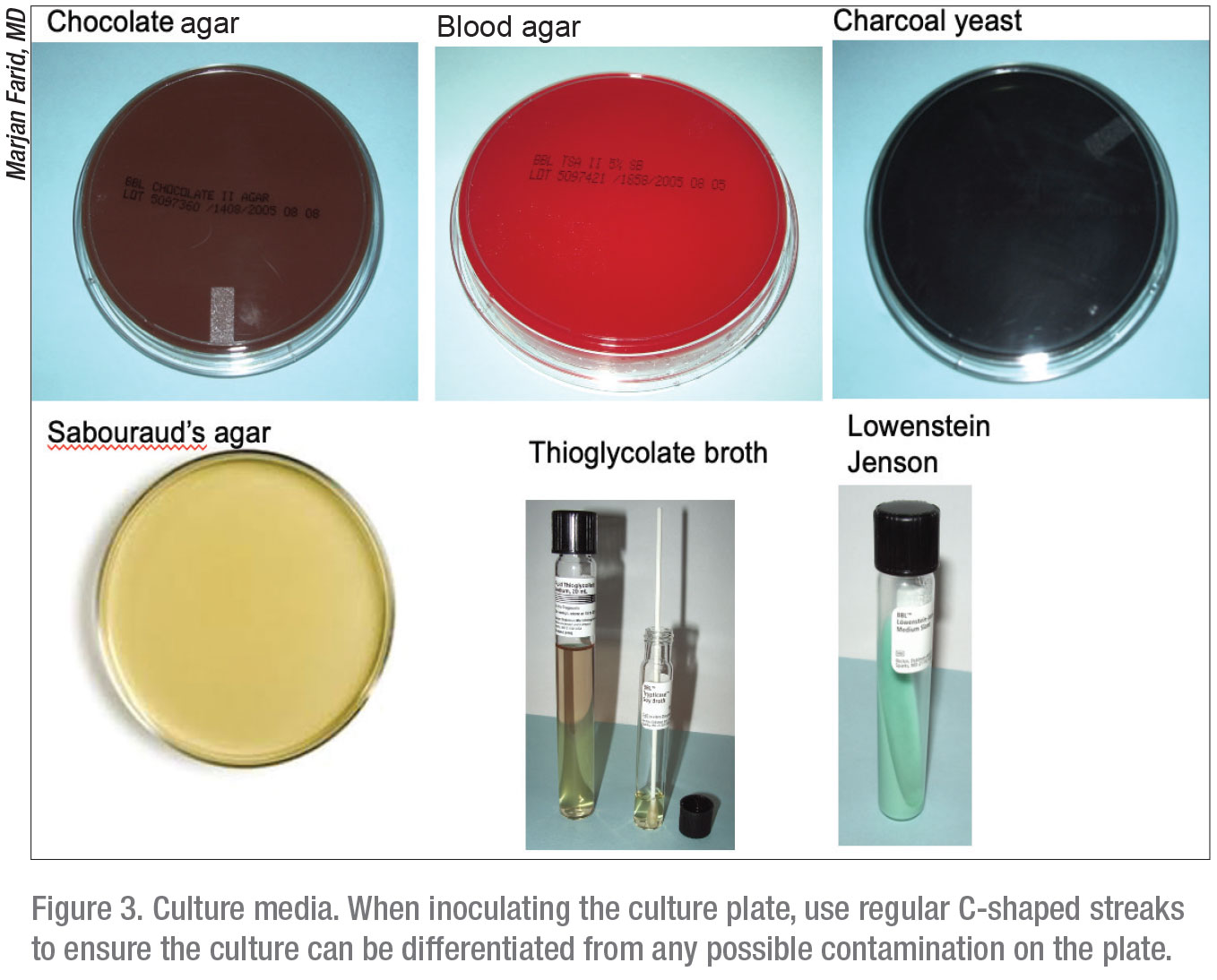

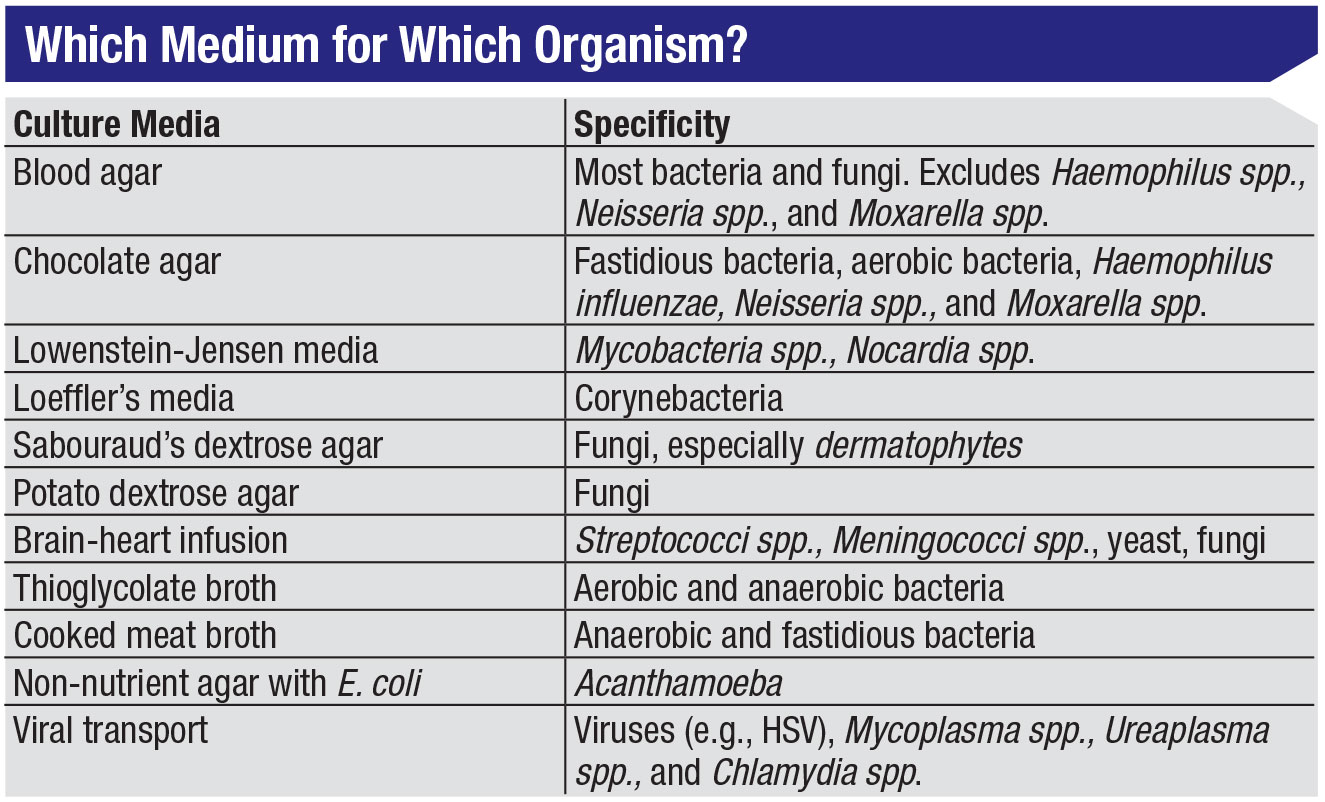

About 15 minutes before she cultures, Dr. Colby removes the proper culture plates from the refrigerator to allow the media to come to room temperature. Most centers have standard culture kits that include media plates for fungal, bacterial, Acanthamoeba and viral material (Figure 3). (See table below.) “I generally don’t culture for virus, because it’s predominantly a clinical diagnosis,” Dr. Colby notes.

The next step is to anesthetize the eye with a numbing agent like proparacaine 0.5%, or any topical anesthetic available in the office to ensure the patient is comfortable. Then, carefully swab or scrape the cornea with light pressure at the edge of the ulcer where the concentration of microorganisms is highest. The sharp edge of an instrument should be tangential to the surface of the cornea to reduce the likelihood of perforation, and you should only move the blade in a single direction.1

The order in which you swab and plate the culture matters, says Dr. Deng. “Your first sample from the cornea will have the most microorganisms,” she explains. “If the lesion is very small, there may be very little organism left to collect for subsequent swabs. Because of this, you’ll want to plate your first culture on the media with the most nutrients—the chocolate agar for suspected bacterial ulcers—for the best chance of a good analysis. Initially, we’d been plating on the blood agar media first, but in our annual lecture from the microbiology lab a few years ago, they instructed us to use the chocolate agar plate first.”

|

Some corneal infiltrates are more accessible than others, but there are multiple collection techniques you can try. For easily accessible infiltrates, Dr. Farid says a calcium alginate swab may be used to procure a culture sample. Deeper infiltrates may require a blade for scraping, such as a Kimura spatula. “If it’s very deep or on the posterior stroma, I pass a braided suture like an 8-0 Vicryl through the infiltrate,” she says. “The microorganisms stick to the suture material, which I culture.” Fungal and protozoal infections may require such sampling from the deeper stromal layer of the cornea.2

When plating your samples, experts say to use regular, recognizable patterns to ensure accurate lab results. “I inoculate the plates using a series of streaks in the shape of a C,” explains Dr. Colby. “You want to inoculate the plate in such a way that the lab will be able to tell if the plate is contaminated, versus if you actually inoculated it. If you use random squiggles, sometimes it can be harder to tell.

“After I’m done with the plates, and the cornea’s been roughed up a bit, I’ll do my smears and stains, which again are done at the edge of the infiltrate and with a blade, such as a sterile Bard-Parker blade. I put them on slides for Gram and Giemsa staining, and occasionally some other specialized stains, depending on what I’m concerned about.

“The stains can sometimes show you something as soon as it’s been done, but that won’t tell you whether the organisms are dead or not,” she continues. “If someone has bacterial keratitis and it’s been treated or partially treated, you might still recover or see organisms on the stain but not necessarily grow anything on the culture. Generally, bacterial cultures will start to show growth within 24 to 48 hours. Fungal cultures take a bit longer for a definitive result, and Acanthamoeba also take longer because of the way the organisms need to be isolated.”

Negative smears may result from an insufficient sample yield, poor staining techniques, prior use of antimicrobial agents, mechanical damage to the cell wall, failure to examine the whole slide or excessive heat fixation.1 Likewise with Gram staining, difficulties can present if there’s a low yield of organisms to begin with. Deposits of melanin, sodium chloride, talcum powder and precipitated gentian violet may also appear as artifacts, making it harder to identify the causative organism.1

“If there’s ever any thought: should I or shouldn’t I? Go ahead and culture,” says Dr. Farid. “You’ll never regret culturing. If you decide to culture after starting treatment, the risk of a false negative is higher because your patient is partially treated and getting a good sample is harder. When in doubt, culture.”

Treatment Options

A broad-spectrum antibiotic, especially if you’re not sure what’s growing yet, is a good starting point, since most corneal ulcers you’ll see are likely bacterial. “Most ulcers will get better with a broad-spectrum fluoroquinolone, even if they’re not specifically sensitive to that,” says Dr. Colby. “For example, though the broader spectrum fluoroquinolones have less efficacy against something like a Gram-positive, for which you could give something specifically targeted, we can give antibiotics frequently enough to get a very high concentration on the ocular surface. I never start a staph ulcer on moxifloxacin, but the reality is that most staph ulcers would get better with moxifloxacin, simply because there’s such a high concentration of medication.”

For smaller, peripheral ulcers, Dr. Farid says she often uses a monotherapy of a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone like moxifloxacin, or besifloxacin, which has better MRSA coverage. “If it looks aggressive and central, I may start the patient on fortified antibiotics such as vancomycin or tobramycin,” she says. “Those drops usually need to be compounded. Initial treatment for most ulcers is hourly antimicrobial drops. We see these patients almost daily until we see a treatment response and know they’re improving. During this time, we also monitor for corneal thinning and perforation.

|

“If the culture results come back as fungal, or if the history is very indicative of fungal ulcer, then we may start the patient on natamycin eyedrops,” Dr. Farid continues. “If I suspect Acanthamoeba or if the cultures come back as Acanthamoeba, I start the patient on Acanthamoeba triple therapy.” The classic triple therapy consists of chlorhexidine 0.02%, polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB) 0.02% and Brolene 0.1%.

All corneal specialists have their own practice patterns, but Dr. Colby recommends waiting for a positive confirmation of Acanthamoeba before initiating treatment, since the therapy process is very long and painful for the patient. Other corneal specialists recommend initiating treatment immediately, before cultures return from the lab, to prevent its possible progression as much as possible.

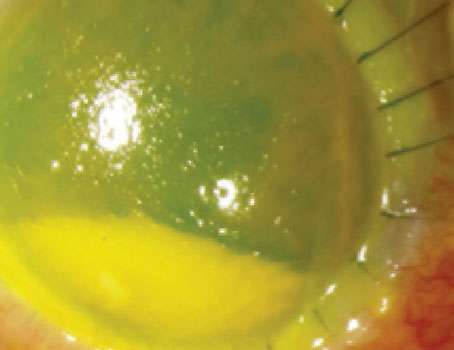

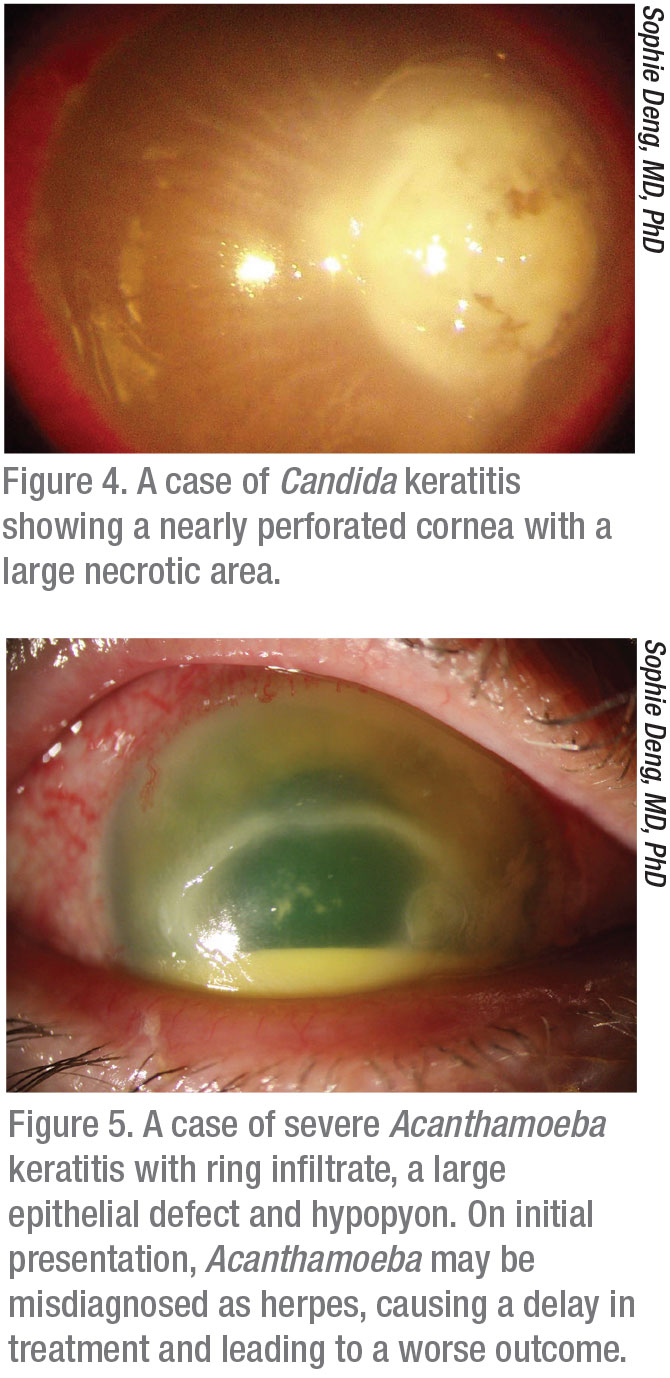

Atypical agents such as filamentous fungi and Acanthamoeba are especially difficult to treat because there’s often a delay in diagnosis, which allows the infection more time to work its way into the cornea (Figures 4 and 5). “Acanthamoeba keratitis is often initially treated as herpes, and it’s also not generally treated first by corneal specialists, but in the community,” Dr. Colby says. “It’s best if you catch Acanthamoeba when it’s still superficial in the cornea. When it gets into the stroma, it becomes very difficult to eradicate. Often, patients present with a red eye and are given TobraDex, a combination of tobramycin and dexamethasone, and then when they don’t ultimately improve, they’re referred for herpes. I recently had a patient who received these different diagnoses, and by the time she got to me, it was clear it was Acanthamoeba, but at that point it wasn’t medically manageable and we had to do a therapeutic keratoplasty.”

Steroids

When you know definitively which infection you’re treating, steroids can help to control inflammation. However, experts caution that steroids can worsen an infection if started too early, especially in the case of fungal keratitis, Acanthamoeba or herpes, when prematurely suppressing the body’s immune system can have serious consequences.

“We want to culture first, get the patient started on the correct therapy and make sure we’re actually killing the microorganisms before starting steroids,” Dr. Farid says. “When I feel that I have control of the infectious organism, then I’d consider starting steroids.” However, Dr. Farid warns that you should still be cautious. “I like to see the patients on steroids back more frequently initially, to make sure they’re not getting worse on the steroids.”

“When you look at the randomized trials that have been done on steroids and bacterial keratitis, the steroids really didn’t have a dramatic effect,” Dr. Colby notes. “However, in a severe ulcer they can be helpful in quelling the inflammation, since a lot of the damage in those cases is from the immune response itself. Again, individual surgeon practice patterns differ, and some start antibiotics and steroids together for corneal ulcers, but that’s generally not what I do. I like to make sure I’m not dealing with a fungus. I like to wait until I have 24 to 48 hours of the antibiotic onboard before giving a steroid, if I’m going to give one.”

Dr. Colby adds that you should always be vigilant for possible fungal infections with your corneal transplant patients. “They’re chronically immunosuppressed, so their symptoms will be more severe and their ability to respond to pathogens will be decreased.” A fungus may find it easier to gain a foothold in the cornea of an immunosuppressed patient.

Antibiotic Resistance

|

Dr. Deng says that antibiotic resistance is concerning, particularly in a tertiary care environment. If your patient isn’t responding to the treatment you’ve prescribed, checking the sensitivity report can point you toward other treatment options. “In general, you shouldn’t base your treatment solely on the sensitivity,” Dr. Deng cautions. “If the patient is responding to treatment, despite the report saying the sensitivity is intermediate or even resistant to the antibiotic that’s been started, you don’t have to change the medications. The patient administers drops very frequently, as often as hourly during the first days, so the amount of medication locally is much greater than the antibody level they test the sensitivity against.

“But if the patient isn’t responding,” she continues, “then I’d go by the sensitivity report. For example, an organism may be resistant to ciprofloxacin but sensitive to moxifloxacin, so I’d switch the patient to moxifloxacin and perhaps add another agent to target Gram-positives or Gram-negatives, depending on the patient’s clinical course.

“Close monitoring of the infection is crucial at the beginning,” she continues. “Because we are the main tertiary eye center in the area, we often see the most severe cases, where the central visual axis is affected and refractory to initial treatment by the referring ophthalmologist. We usually start fortified vancomycin and tobramycin/gentamicin if microbial infection is suspected.”

Occasionally, the lack of response to treatment may be due to an incorrect or incomplete diagnosis. “If you need to reevaluate the causative agent—perhaps it’s a fungal infection as well as a bacterial infection—you’ll have to re-culture as well,” says Dr. Deng. This can prove challenging, since a partially-treated ulcer may have a very low yield of microorganisms for analysis and prior treatment may skew results.

Corneal Biopsy

“Sometimes despite our best efforts, some corneal ulcers remain recalcitrant,” Dr. Farid says. “In these cases we may move on to a corneal biopsy.” A corneal biopsy may be necessary when there’s no response from the organisms that grew on the first culture, or a poor response. In these cases, a biopsy of the deeper corneal tissues may reveal the elusive organism.

“Depending on where the infiltrate is, we may use a very small trephine punch that’s about 3 mm,” she explains. “We trephinate partially into the infiltrate and get a lamellar section of the diseased cornea to send for pathology. The risk here is perforation, so we have to be cautious and make sure we’re not removing so much of the cornea as to cause a perforation.”

Therapeutic Transplants

“In very severe cases when the cornea isn’t healing appropriately or the ulcer is very visually significant, we may move on to a therapeutic corneal transplant, where we’ll remove the entire infection, depending on the size and location of the infiltrate,” Dr. Farid says. “Here, patient history is important. If they’re immunocompromised or have rheumatologic disorders that would make them poor healers, these conditions would need to be assessed. Some patients will need systemic therapy as well. Fungal ulcers that are very deep may also require oral antifungals.

“We may also consider a therapeutic transplant if the eye is starting to grow blood vessels in from the periphery, because we know a corneal transplant is likely in the future anyway,” Dr. Farid continues. “Doing that therapeutic transplant before the patient gets a lot of peripheral neovascularization in the cornea can make the long-term chances of survival of the transplanted tissue better. That said, you also want to have the infection as well-treated as possible before heading for a transplant. There’s a sweet spot for the therapeutic transplant.”

Hypopyon or Endophthalmitis?

|

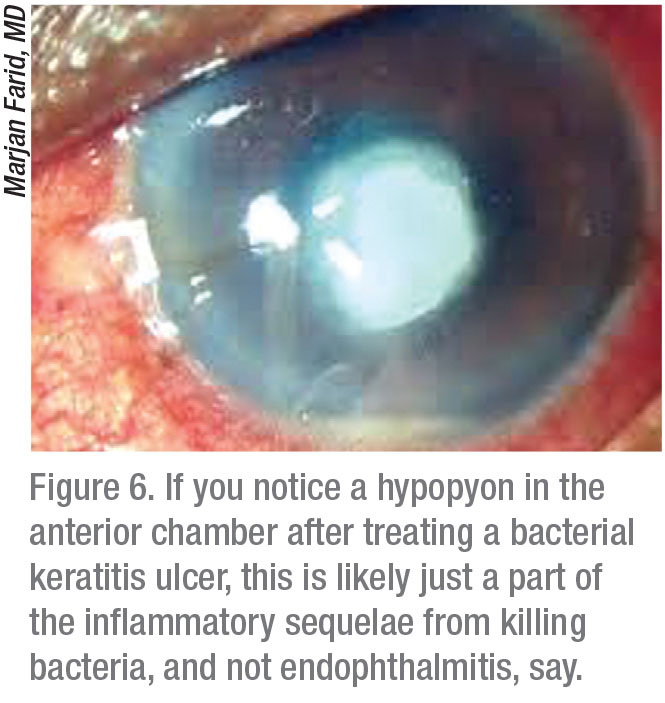

If you’ve given a patient the appropriate antibiotic for a garden variety Pseudomonas bacterial ulcer, and one or two days later, that patients returns with a hypopyon, Dr. Colby says don’t panic (Figure 6). “The white cell layer in the front of the eye doesn’t mean the infection has gone into the eye—it’s part of the inflammatory sequelae from killing the bacteria,” she explains. “This finding often generates an urgent referral to a cornea specialist, but it’s not endophthalmitis.”

“The way to distinguish endophthalmitis from a pure hypopyon in anterior chamber is through a B-scan to see whether there’s any vitreous opacity,” Dr. Deng explains. “The caveat, though, is that when the patient has such severe inflammation in the front of the eye, there’s often some spillover inflammation—not necessarily infection—into the posterior pole. If there’s high suspicion for endophthalmitis—for example, if the patient has had cataract surgery and the patient presented with hypopyon before the corneal ulcer presented—then you would strongly consider endophthalmitis as one of the etiologies of the hypopyon. But if the patient presents with a bacterial corneal ulcer first and this leads to a hypopyon, then the chance of this eye having endophthalmitis as a presenting symptom is less likely.”

Endophthalmitis must remain on your radar for a fungal ulcer, however. Dr. Deng points out that fungi tend to penetrate deeply into the cornea, even into the anterior chamber. “This could lead to endophthalmitis,” she says. “If there is any concern of endophthalmitis, we always have our retina colleagues involved.” REVIEW

None of the doctors has financial disclosures related to any of the products mentioned.

1. Basheer N. Scraping in corneal ulcers. Kerala J Ophthalmol 2020;32:1:97-101.

2. Leck A. Taking a corneal scrape and making a diagnosis. Community Eye Health 2009;22:71:42-3.