|

|

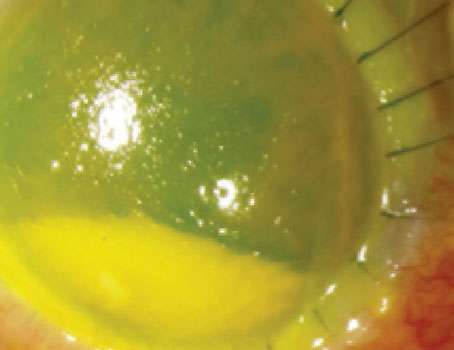

Figure 1. Dendrites with dichotomous branching and distinct terminal bulbs are a classic presentation in herpes simplex. (Sources: Sonal Tuli, MD) |

Considering its rate of infection—estimated to be 67 percent of the global population under age 501—herpes simplex will continue to manifest ocularly with a range of complications and risks to patients.

Herpes simplex virus type 1, primarily transmitted by oral contact, commonly infects people as children, with a lifelong risk of symptomatic or asymptomatic viral shedding.2 In many, HSV-1 will show up as a cold sore or fever blister, but ocular symptoms can present as blepharitis, conjunctivitis, epithelial keratitis, stromal keratitis, endotheliitis, iritis, trabeculitis and retinitis.3 Herpes simplex keratitis and herpes zoster ophthalmicus each pose significant risk to a person’s vision, making accurate diagnosis crucial to its treatment and ongoing prevention.

We spoke with several cornea specialists about what you should look for in order to properly diagnose ocular herpes and which treatment methods show the most success.

Making a Diagnosis

Pain isn’t one of the primary complaints patients will have when it comes to herpes simplex keratitis. “They’ll come in with either red eye, blurred vision or light sensitivity,” says Sonal Tuli, MD, MEd, a professor and chair of the department of ophthalmology at the University of Florida. On the other hand, zoster presents with very distinct skin lesions, redness and swelling, and patients will have a tingling, painful sensation. “It can initially be misdiagnosed as just a rash or an allergy or bacterial infection, but then patients will get these blisters that break down and cause crusting and scarring. Then, it’s pretty obvious it’s zoster,” Dr. Tuli says.

Knowing what to look for during the exam will help you determine the type of virus. “If it’s on the surface of the cornea, this is classically what people see in the textbook as a herpes simplex dendrite. It’s a very specific appearance—you can’t miss it,” says Bennie Jeng, MD, chair of the department of ophthalmology and director of the Scheie Eye Institute at Penn Medicine in Philadelphia.

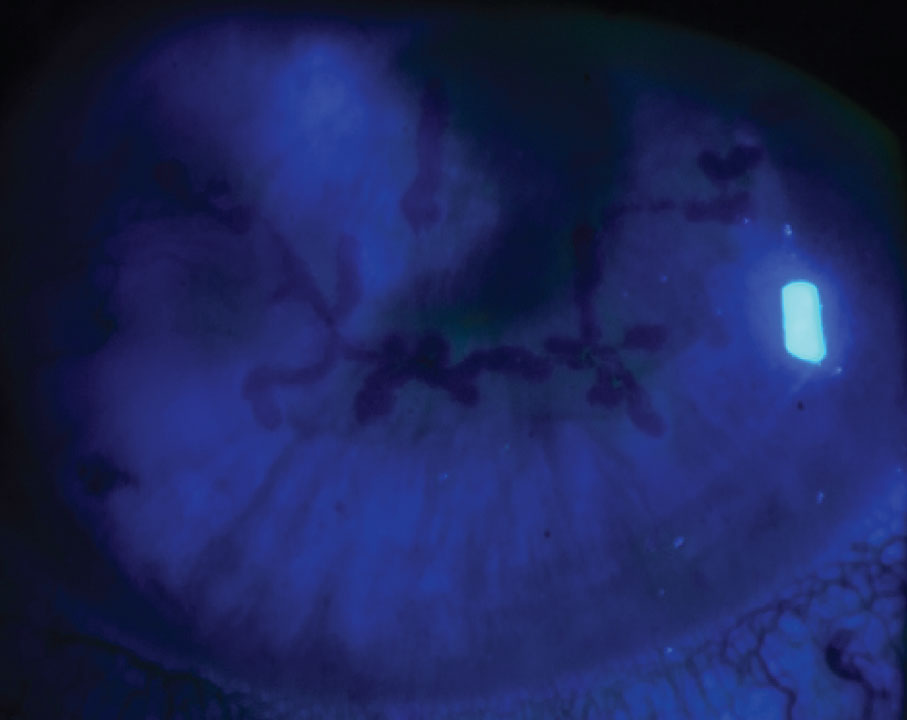

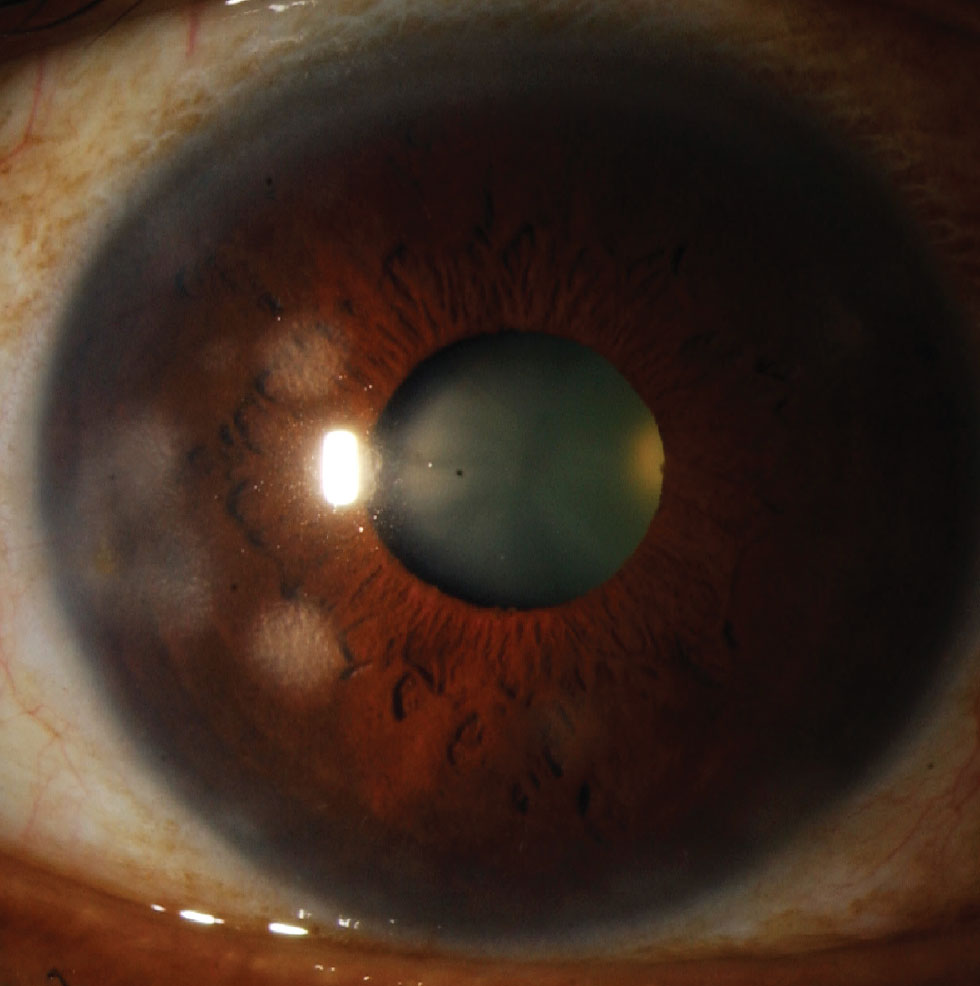

Epithelial keratitis presents with linear dendrites with branches featuring distinct terminal bulbs. To confirm this diagnosis, fluorescein stain should be used for the center of the dendrites and rose bengal on the periphery, says Dr. Tuli. “That’s the classic dendrite staining. The problem with simplex is it doesn’t just cause dendrites—it can cause infection in any of the layers of the cornea, and even in the anterior chamber,” she says. “Those become a little harder to diagnose because the stromal inflammation can be missed. It may manifest as these little hazy patches in the cornea, and if you don’t treat that, then blood vessels can start growing into the cornea and cause pannus or interstitial keratitis.”

Dendrites for HZO look subtly different. “Zoster dendrites, referred to as pseudodendrites, have tapered edges and lack the distinct terminal bulbs,” says Deepinder K. Dhaliwal, MD, LAc, a professor of ophthalmology at the University of Pittsburgh.

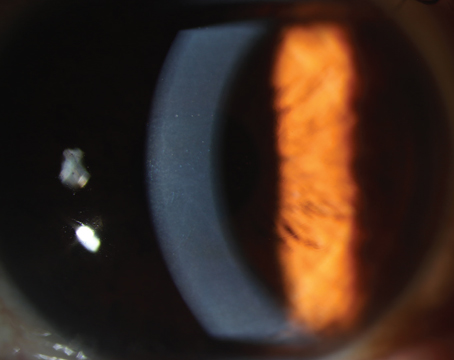

Asking patients the right questions can help narrow down the diagnosis. “When you get stromal involvement of the middle of the cornea and you get herpes stromal keratitis, it can be virtually impossible to tell which virus is causing the inflammation because it looks identical,” Dr. Jeng says. “Ask the patient’s history: Have you ever had a dendrite before; have you had zoster on the skin before? Those things will point to having one diagnosis or the other. Both can cause endotheliitis, so it’s also virtually impossible to tell which virus is causing it just by looking at it.”

|

|

Figure 2. Nummular keratitis appears as coin-shaped lesions in the middle of the stroma as a sign of inflammation, which is often managed with steroids. |

If any doubt exists, ordering a herpes PCR is a good idea. Alan Carlson, MD, a professor of ophthalmology and chief of corneal and refractive surgery at Duke Eye Center, says he’ll order a PCR if there’s a question whether the infection is herpetic. “I do recommend obtaining a PCR test, which has replaced the culture, if it’s active epithelial herpes, and if it’s stromal keratitis, I’ll often get a blood test for HSV-1 and HSV-2 because I’ve had several patients now who were able to come off of chronic antiviral medication because they were serologically negative for this virus,” Dr. Carlson says.

This has been helpful especially since Dr. Carlson has noticed an uptick in Epstein-Barr virus, which can resemble HSK. ESV can show up ocularly via conjunctivitis, dry eye, keratitis, uveitis, choroiditis and retinitis.4 “It’s more likely Epstein-Barr if it’s bilateral, and it involves the stroma at various levels, particularly in the periphery of the cornea. If you present with a deeper infiltrate, we’ll see the Epstein-Barr virus, so being able to exclude herpes simplex serologically has been valuable,” says Dr. Carlson.

If the dendrites don’t have the classic presentation, Dr. Tuli says several factors could cause that, including medication toxicity or a healing epithelial defect.

Dr. Dhaliwal says Acanthamoeba keratitis is commonly confused for HSK. “If there’s a dendrite or something that looks like a dendrite in a contact lens wearer and they may or may not have more pain and irritation, we think of Acanthamoeba keratitis before we think of herpes, and the easiest way to make this diagnosis is to remove all of the involved epithelium and just send it to the microbiology lab,” she says. “They can do a PCR for Acanthamoeba and you definitely don’t want to miss the diagnosis of Acanthamoeba because if you catch it early and you remove all the involved cornea, you just cured the patient. It’s really impactful.”

This may come to light during the course of treatment, she adds. “HSK resolves pretty quickly, so if there’s a situation where the herpes isn’t getting better, you’ve got to rethink the diagnosis.”

Diagnosis may be further challenged if the patient has other forms of ocular surface disease, continues Dr. Carlson. “If they have ocular rosacea in addition to viral keratitis, they can be more prone to inflammation and you want to be aware of that because they may require steroids for a longer period of time.”

Treatment Strategies

Once the correct virus has been identified, treatments include oral and topical antivirals, and steroids.

“The treatment for epithelial disease is primarily antivirals,” Dr. Tuli says. “You can use oral or topical, and there’s advantages and disadvantages to each. There’s less resistance to topical antiviral medications because they’re not used globally for other herpes infections, but they can be toxic and patients might not tolerate them, or children might not tolerate putting in drops every couple of hours. In that case, oral antivirals might be more useful; they’re less toxic and easier to take, but the disadvantage is that it does have to get absorbed into your body.”

Acyclovir is often mixed with lactose, she says, so if someone is lactose intolerant they may not absorb it. “People who’ve had abdominal surgeries may not tolerate it, and anyone with liver or kidney failure may not be able to take those medications because they could build up in their body,” says Dr. Tuli. “Deeper infections are typically treated with steroids to calm down the inflammatory reactions, and that often prevents the complications such as scarring and blood vessel growth.”

| The Importance of the Shingles Vaccine Herpes zoster is more commonly known as shingles and often appears in the form of rashes and blisters. Not only can shingles lead to blindness, but more than 10 percent of people who get shingles develop postherpetic neuralgia.6 What’s especially concerning to health-care providers, however, is not only the incidence of shingles, but the age of people developing it. “We’re clearly seeing shingles occur in younger patients, and we don’t exactly know why,” says Alan Carlson, MD, a professor of ophthalmology and chief of corneal and refractive surgery at the Duke Eye Center. A 2016 study, showed the incidence of herpes zoster increased four times over a 60-year period in those under age 50.7 Bennie Jeng, MD, chair of the department of ophthalmology and director of the Scheie Eye Institute at Penn Medicine in Philadelphia, says this age-shift has been coming on progressively. “We used to think that if anyone under the age of 60 developed shingles, we had to work them up for some sort of immunosuppressive condition whether it was cancer or HIV,” he says. “But now we see people in their 50s or even their 40s having it.” These anecdotes make it even more vital that ophthalmologists tell their patients about the efficacy and safety of the newest shingles vaccine (Shingrix), which has faced a somewhat slow adoption rate. The Shingrix vaccine is recommended in people over age 50 and has proven to be much more effective than its predecessor, Zostavax. In adults 50 to 69 years old with healthy immune systems, Shingrix was 97 percent effective in preventing shingles; in adults 70 years and older, Shingrix was 91 percent effective.8 Some within the eligible population are hesitant to get vaccinated for a couple of reasons, says Deepinder K. Dhaliwal, MD, LAc, a professor of ophthalmology at the University of Pittsburgh. “Shingrix is a great vaccine, it just hurts. And you need two shots,” she says. “I try to counsel all my patients to get it but people are a little vaccine hesitant because of COVID; they have vaccine fatigue. But it’s critically important as ophthalmologists that we educate patients on how devastating zoster is to the eye, much more than simplex.” Vaccination is an effective way to prevent this from happening, says Dr. Jeng. “Not only does the CDC recommend it for anyone aged 50 and over, but so does the American Academy of Ophthalmology. When people do get zoster, it’s really bad, so if we can get the message out to get vaccinated for shingles then we will have accomplished something major.” |

“Each entity is treated differently,” says Dr. Jeng. “If you see herpes simplex and it’s epithelial disease, then you can either treat it with topical medications or you can treat it with oral medications. Topical medications would include trifluridine or ganciclovir. You can also treat orally with either acyclovir, valacyclovir or famciclovir. If it’s zoster, then there’s been some evidence that ganciclovir might work topically. Orals are also a good choice.”

Dr. Dhaliwal believes topical agents like ganciclovir are “fantastic.” “I don’t typically use Viroptic anymore because it’s preserved in thimerosal and it can have a lot of toxicity,” she says. “I would recommend either using ganciclovir or oral agents which are wonderful for epithelial disease.”

Dr. Carlson tends to avoid the topical antivirals in certain situations. “As somebody that’s in cornea practice, I see a lot of surface disease, so I tend to favor the oral medications based on the safety profile, the cost effectiveness, and the lack of topical toxicity,” he says. “A lot of the topical antivirals are toxic to the surface, so if you’ve got a dry eye or an epitheliopathy or ocular surface disease that’s been made worse by surgery, adding the toxicity of another medication like a topical antiviral could make the patient worse.”

Not to mention, if it’s stromal disease, topical medications don’t work, says Dr. Jeng. “This is a common mistake,” he says. “There are two types of stromal disease: necrotizing, where there’s actually destruction of tissue; and non-necrotizing. Necrotizing suggests that there’s active viral replication, and for that you need to treat with antivirals. If there’s non-necrotizing disease and it’s just inflammation, we treat that with a combination of steroids and oftentimes we cover with antivirals, just in case, but really steroids are the mainstay of treatment.”

Dr. Carlson also uses steroids when dealing with a stromal infiltrate. “I’m a huge fan of topical steroids in that setting and I like to cover with a prophylactic dose of an oral antiviral,” he says. For example, he continues, if a patient had been on 1 g of Valtrex twice a day but no longer has active epithelial HSV but there’s stromal inflammation, he would continue the 1 g of Valtrex prophylactically daily and add the topical steroid based on the severity of the inflammation.

But what should you do about treating stromal disease that looks identical in both zoster and simplex? “In zoster we tend to use higher doses because it’s a hardier virus, so everything is doubled,” Dr. Jeng says. “For instance, if we’re doing 500 milligrams of valacyclovir three times a day for simplex then we would do 1,000 milligrams three times a day for zoster.”

This high dose of antivirals in the initial zoster episode for at least two to four weeks is going to help prevent the biggest complication of zoster: postherpetic neuralgia, says Dr. Tuli. “People believe, after the first three or four weeks, that the corneal disease is immune-mediated, and we usually treat that with steroids. At this point, it becomes uncertain if the antivirals actually help with the corneal disease.”

Dr. Dhaliwal personally doesn’t use an antiviral cover for zoster. “Once they get the full oral antiviral dosing of valacyclovir or one of the antivirals then I typically just treat with steroids, even if they have a stromal keratitis or an interstitial keratitis,” she says. “I personally haven’t had any situations where there was melting or problems with this. I’ll use antivirals if there’s a persistent uveitis. That’s another thing that people need to know: herpes-related uveitis is differentiated from typical uveitis because you get a higher pressure in the eye.”

The efficacy of using antivirals prophylactically in HZO is the aim of the Zoster Eye Disease Study, co-chaired by Dr. Jeng. Much like the Herpetic Eye Disease Study (HEDS) did in the ’90s for treating herpes simplex keratitis with acyclovir, the ZEDS is doing the same for zoster. The National Eye Institute-supported randomized clinical trial is exploring whether one year of suppressive valacyclovir reduces zoster complications.5

“This is specifically about preventing recurrent disease,” Dr. Jeng says. “If you get an infection in your eye, you can always have more episodes. The question is, if we treat it with low-dose antivirals, will that decrease your chance of recurrence? What the HEDS showed was that for the non-necrotizing stromal keratitis, if you prophylax them with low-dose acyclovir (400 mg twice a day), you decrease your risk of having a recurrent episode by 40 percent. Since this type of disease causes vision loss, it’s important to try to prevent recurrent episodes.”

Many people are under the impression that zoster can be treated the same as HSK to prevent recurrences, says Dr. Jeng. “We just don’t have good data for zoster to support that, and that’s the whole reason behind ZEDS.”

Dr. Jeng expects the study will continue for one to two more years, and the endpoints will look at recurrences at the one-year mark and again at 18 months to see if there’s some sort of lasting effect.

And that’s one of the biggest questions: how do you deal with these patients moving forward?

“Once you’ve resolved their dendrite, what do you do?” muses Dr. Dhaliwal. “Dendrites typically result in scarring and you have to be really careful because they could get recurrent keratitis. I often keep them on a low-dose of antivirals for a long time, and that’s been shown to be relatively safe. The thing that the patients need to know is that the virus lives in the trigeminal ganglion so they’ll never get rid of it; it’s always going to rear its ugly head when they’re stressed out or with UV exposure.”

Final Thoughts

“Herpes is often so confusing to people, but it really doesn’t need to be,” says Dr. Dhaliwal. “Compartmentalize it, so first: is it zoster or simplex? If it’s simplex, is there live virus or not? Taking it step by step is super helpful.”

Returning to her earlier point, Dr. Dhaliwal says, “If it’s not resolving and you have a dendrite in a contact lens wearer, please think of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Unless it’s a classic dendrite, I would have a very low threshold to remove all of the affected epithelium and send it to the lab. That used to be the treatment for herpes, removing the dendrite with a cotton swab and debulking the particles, so even debridement is a treatment as well. It really could be curative, even in both situations, and the worst thing that you did is create an epithelial defect which should heal. But Acanthamoeba is a problem and the numbers aren’t going down.”

Dr. Carlson also recommends that physicians remain mindful of treatment costs. “I’ve had some patients who were prescribed the newer medication Zirgan (ganciclovir gel) come back and say that they couldn’t afford it,” he says. “If you do prescribe that, make sure that the patient has a coupon or something to help absorb the costs, because all of the other things we’ve talked about—the topical medications, the steroids, the oral Valtrex, the oral acyclovir—all of those are relatively cheap compared to Zirgan, and if you prescribe it to a patient who doesn’t have insurance, they may get a little sticker shock. You just need to be aware of that.”

Looking toward the future of treatments, Dr. Tuli says the Holy Grail for simplex and maybe zoster wouldn’t be a treatment for the surface of the eye or the eye itself, but one that would shut the herpes virus replication down where it originates, in the trigeminal ganglion. “There are several labs, including mine, that are looking at this,” she says.

Dr. Carlson, Dr. Dhaliwal and Dr. Tuli report no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Jeng is a consultant for Glaxo-Smith Kline, Oyster Point and Santen. He owns stock in Kiora.

1. Looker KJ, Magaret AS, May MT, Turner KM, Vickerman P, Gottlieb SL, Newman LM. Global and regional estimates of prevalent and incident herpes simplex virus type 1 infections in 2012. PLoS One 2015;10:10:e0140765.

2. Scott DA, Coulter WA, Lamey PJ. Oral shedding of herpes simplex virus type 1: a review. J Oral Pathol Med 1997;26:10:441-7.

3. Valerio GS, Lin CC. Ocular manifestations of herpes simplex virus. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2019;30:6:525-531.

4. Matoba AY. Ocular disease associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection. Surv Ophthalmol 1990;35:2:145-50.

5. Cohen EJ, Hochman JS, Troxel AB, Colby KA, Jeng BH; ZEDS Trial Research Group. Zoster Eye Disease Study: Rationale and Design. Cornea 2022;1;41:5:562-571.

6. Complications of Shingles. https://www.cdc.gov/shingles/about/complications.html. Accessed Oct. 19, 2022.

7. Kawai K, Yawn BP, Wollan P, Harpaz R. Increasing incidence of herpes zoster over a 60-year period from a population-based study. Clin Infect Dis 2016;15;63:2:221-6.

8. Shingles Vaccination. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/shingles/public/shingrix/index.html. Accessed Oct. 19, 2022.