These are just some of the results from this month’s survey on cataract surgery technique. This time, 43 surgeons, or 8 percent of the 500-surgeon sample, responded with their opinions on cataract surgery. Here’s a look at their responses.

Managing Astigmatism

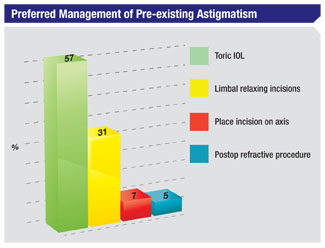

Managing Astigmatism When faced with a patient with astigmatism, 57 percent of the survey’s respondents say they prefer to use toric IOLs. Thirty-one percent like limbal relaxing incisions, 7 percent place their entry incision on-axis and 5 percent will use a postop refractive procedure to handle the astigmatism.

“Toric IOLs are more predictable and stable than LRIs,” says a surgeon from Texas. Douglas Liva, MD, of Paramus, N.J., says he prefers toric lenses because “they’re very accurate, and I can always follow them with PRK or LRIs.” Monterey Park, Calif., surgeon Calvin Eng likes toric lenses because they’re “predictable and reimbursable.” In the LRI camp, surgeons say the incisions are effective and easy to do. “Limbal relaxing incisions are inexpensive, easy and fairly reliable,” avers a California surgeon. Harvey Rosenblum, MD, of New York City, says he likes to use LRIs because of their efficacy, adding, “Patients are reluctant to receive toric IOLs.” An ophthalmologist from Indiana who prefers LRIs says the incisions are “easy and cheap, and effective enough to meet a patient’s needs.”

Surgical Technique

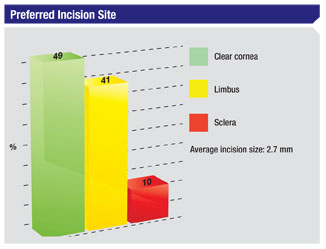

Clear corneal incisions under topical anesthesia remain the preferred approach for the surgeons in our survey.

Forty-nine percent of the respondents say they use clear corneal wounds, 41 percent enter via the limbus and 10 percent use scleral tunnels. The average width of surgeons’ entry incisions on the survey is 2.7 mm. “Clear corneal incisions are in an easy location and only induce 0.5 D of astigmatism,” says a surgeon from California. Another surgeon from California agrees, saying, “They’re simple and quick.” Lawrence Zweibel, MD, of Smithtown, N.Y., says he prefers clear corneal wounds because of their “ease and safety.” Dr. Liva says that though he routinely uses clear corneal incisions, they’re not perfect. “They require sutures sometimes to prevent seepage,” he says.

|

A small number of surgeons—13 percent—say they’re considering switching to a different incision location, however. Two-thirds of the surgeons contemplating a switch say they think they’ll go to a limbal location, and a third will move to clear cornea. Herbert Nevyas, MD, of Marlton, N.J., says he may switch to limbal wounds because the incisions are “safer,” while Dr. Rosenblum of New York says he may move to limbal incisions because he thinks they offer more stability.

Though some surgeons may be second-guessing their incision sites, not many seem to be questioning their stance on bimanual phaco, also known as micro-phaco. Ninety-three percent of the respondents say they don’t do it, and 90 percent of them say they’re unlikely to start doing it within the coming year. Common reasons cited are the lack of IOL options that can go through sub-2 mm incisions and the fact that induced astigmatism is already very low with 2.2-mm incisions. “I see no advantage to micro-phaco,” says Dr. Liva. “Coaxial can be performed through a 2.2-mm incision.” A surgeon from California also questions how it benefits him. “I’m comfortable with my current technique using a 2.4-mm incision,” he says. “It’s difficult to find an IOL to put in the smaller incisions [of micro-phaco], and there are diminishing returns with the smaller incisions.” A surgeon from Texas says he’s shying away from micro-phaco out of “concern about corneal burns.” Many surgeons just don’t think micro-phaco adds anything to the procedure. “My current technique works,” says a surgeon from Maine. An ophthalmologist from California thinks it’s a “less-effective procedure,” while a surgeon from Indiana says “there’s no advantage apparent.” Luther Fry, MD, of Garden City, Kansas, says that micro-phaco offers “no advantage over 1.8-mm Stellaris coaxial.”

Though some surgeons may be second-guessing their incision sites, not many seem to be questioning their stance on bimanual phaco, also known as micro-phaco. Ninety-three percent of the respondents say they don’t do it, and 90 percent of them say they’re unlikely to start doing it within the coming year. Common reasons cited are the lack of IOL options that can go through sub-2 mm incisions and the fact that induced astigmatism is already very low with 2.2-mm incisions. “I see no advantage to micro-phaco,” says Dr. Liva. “Coaxial can be performed through a 2.2-mm incision.” A surgeon from California also questions how it benefits him. “I’m comfortable with my current technique using a 2.4-mm incision,” he says. “It’s difficult to find an IOL to put in the smaller incisions [of micro-phaco], and there are diminishing returns with the smaller incisions.” A surgeon from Texas says he’s shying away from micro-phaco out of “concern about corneal burns.” Many surgeons just don’t think micro-phaco adds anything to the procedure. “My current technique works,” says a surgeon from Maine. An ophthalmologist from California thinks it’s a “less-effective procedure,” while a surgeon from Indiana says “there’s no advantage apparent.” Luther Fry, MD, of Garden City, Kansas, says that micro-phaco offers “no advantage over 1.8-mm Stellaris coaxial.”

Thirty-two percent of surgeons perform coaxial micro-incision surgery, or C-MICS, which doesn’t separate the infusion and aspiration as micro-phaco does, yet can be done through a very small, in some cases 1.8-mm, incision. “C-MICS results in faster healing,” avers a surgeon from Florida. An ophthalmologist from California says the surgery results in “less induced astigmatism,” while a surgeon from Indiana says he finds that, with C-MICS, “the incisions are easy to manage and match the lens insertion size.” Though some surgeons don’t think C-MICS improves outcomes for them, such as a Missouri physician who says he “can’t see an advantage with C-MICS,” others might do the procedure if they could, but simply don’t have access to it. “I’m not equipped to do it,” says California’s Dr. Eng. Dr. Rosenblum says it’s “not available” to him.

|

When it comes time to insert an IOL, 12 percent say they mix different types of premium IOLs on occasion.

Preparing the Patient

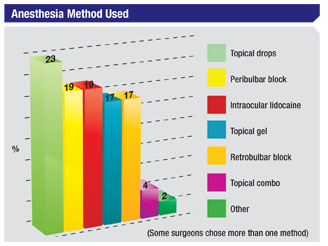

Forty-four percent of the respondents use some method of topical anesthesia. Twenty-three percent use topical drops, 17 percent use topical gel and 4 percent use a combination of topical methods. Nineteen percent also use intraocular lidocaine. In terms of nerve blocks, 19 percent use peribulbar blocks and 17 percent use retrobulbar.

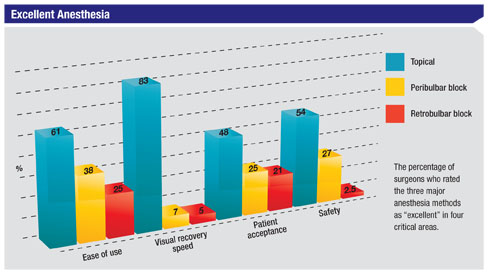

Sixty-one percent of the surgeons think topical anesthesia is excellent in terms of ease of use, 83 percent rate it as excellent with regard to the speed of visual recovery and 54 percent say it has excellent safety.

“Topical anesthesia is excellent,” says a surgeon from California. “I almost never get a complaint. It’s also safe and easy.” Dr. Liva says that topical anesthesia has been so successful for him that he “rarely finds a need to supplement it with intraocular lidocaine.”

Peribulbar blocks have a solid fan base, however. Dr. Eng says that peribulbar blocks are “the most effective and comfortable method for a multilingual patient population,” and that with topical anesthesia, “intraoperative movement is too risky.” A surgeon from Wisconsin agrees, saying, “A non-moving eye makes for the safest surgery.” A Florida surgeon says simply, “Peribulbar blocks are easy to use.”

Peribulbar blocks have a solid fan base, however. Dr. Eng says that peribulbar blocks are “the most effective and comfortable method for a multilingual patient population,” and that with topical anesthesia, “intraoperative movement is too risky.” A surgeon from Wisconsin agrees, saying, “A non-moving eye makes for the safest surgery.” A Florida surgeon says simply, “Peribulbar blocks are easy to use.”

When asked about the best infection prophylaxis besides povidone iodine, 46 percent think preoperative topical fluoroquinolones are best, 21 percent prefer postop fluoroquinolones, 17 percent like intracameral injections of antibiotics, 10 percent put antibiotics in the infusion bottle and 2 percent use subconjunctival antibiotic injections. Four percent chose a method other than these.

Parting Thoughts

Every surgeon has a tip that he thinks is key to getting a good outcome. Here is our panelists’ advice.

“I use different choppers depending on the nature of the lens,” says Dr. Rosenblum. “I use a broad, spatulate type for soft lenses, and a smaller, pointed one—MacKool style—for the firm or the brunescent lens.” Dr. Liva also says the surgeon has to customize his approach to the cataract. “Be familiar with multiple techniques for nucleus removal so that if your primary technique isn’t suitable, you can switch to a different one,” he says. “For instance, for a soft posterior subcapsular cataract, cracking is difficult and unnecessary; simple prolapse into the anterior chamber is easier and faster.”

A Florida surgeon says he uses “atropine for a week preop for Flomax patients.” When faced with similar patients, Dr. Fry advises: “Use epi-shugarcaine for the Flomaxed iris.” A Texas ophthalmologist says sometimes phaco may not be the best option. “If a patient has a hard, advanced cataract and you are unsure whether or not to do phaco, then perform extracapsular cataract extraction,” he says. A surgeon from California has an interesting tip for certain patients: “I use a Honan cuff on short eyes and IFIS cases to shrink the vitreous and give me more room to work,” he says.

A number of surgeons emphasized the importance of simply seeing what you’re doing. “Good visualization is a must,” says New York’s Dr. Zweibel. “Never take your eyes off of the field,” concurs Laurence Rubin, MD, of Bethpage, N.Y. A surgeon from Arizona says, “Be comfortable in your chair and have an excellent view of the eye.”