|

Early Days

I was chief resident at Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco at the time Dr. Grizzard did his fellowship with George Hilton across the bay in Oakland. I had the privilege of spending time with Dr. Hilton in the OR during that year. He always operated in the evening, after office hours, when things quieted down. He was very methodical; every detail was placed in a cubbyhole. “Paul, there are 13 causes of cystoid macular edema,” he would say, reciting them in the same order every time he gave “the sermon.” He also said there are 10 steps to retinal detachment surgery (scleral buckling), and he demonstrated how one step followed the other. He made retinal surgery appear very simple. He sparked my interest in retinal disease and helped me obtain a retina fellowship at Barnes Hospital in St. Louis with Ed Okun, MD. After I completed my retina fellowship, I hung my shingle in San Diego but kept in touch with Dr. Hilton, a mentor, and I frequently asked his advice in the early days of my practice.

|

Howard Shatz, MD, started the West Coast Retina Study Club in the early 1980s and I attended a meeting in San Francisco where Dr. Hilton presented five cases of pneumatic retinopexy. I told him I had done two cases and asked where he got the idea. To my amazement he said he heard Ed Boldry’s talk at UCSF. At that meeting Neil Kelly said he also independently did a few cases.

Dr. Hilton subsequently presented his experience with 20 cases to the AAO and on the audiotape, which I cherish to this day, he magnanimously stated that Dr. Kelly in Sacramento and myself were also doing this procedure. We then put all our data together and published our experience in several papers.8-10 We subsequently shared our experience with others in an AAO instruction course consecutively for more than a decade (See Figures 1 & 2).

|

Dr. Grizzard and I subsequently put on a seminal meeting in San Diego. We invited anyone who was performing the operation to present his or her data, which we eventually published.11 All the presentations were similar, with about the same positive results and complications. We realized we were onto something good.

The Trial Begins

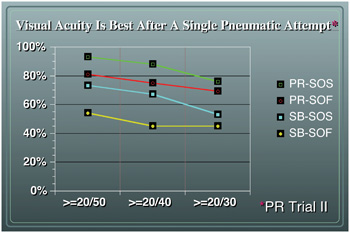

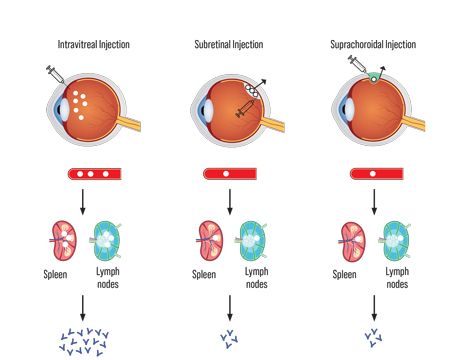

The Pneumatic Retinopexy Clinical Trial enrolled about 100 patients into the scleral buckle group and another 100 into the pneumatic retinopexy group. The process of randomization remarkably produced two very similar groups. After following the patients for six months, the data showed that pneumatic retinopexy reattached the retina almost at the same frequency as scleral buckling, but most importantly, quickly improved vision to the pre-detachment level more often than scleral buckling. It also showed that a failed pneumatic did not harm the eye. Writing the manuscript was quite challenging, for there was no Internet and no one was really using a computer.

There were many revisions of the paper sent between San Diego and Tahiti (via DHL). Once the presentation was accepted by the AAO, I requested Dr. Lincoff to referee the paper. He was well-known as one who did not embrace the procedure, and I felt if he was positive about the paper, more surgeons might accept the operation. Dr. Lincoff did not disappoint; he was fair, pointed out all the weak points of the study, but also admitted there was some validity to the operation. After 18 more months of follow-up we presented the PR Clinical Trial two-year data, again at the AAO which showed that the operation was lasting and that almost 90 percent of patients with detachment of the macula regained reading vision.12,13

|

Pneumatic retinopexy has been controversial since the beginning and remains so today. Some surgeons were so concerned about the conclusions of the trial that they requested the raw data to personally review. Many published their poor initial experience with the procedure. Adverse events were quickly disseminated, several as single case reports.14-21 Rarely were the publications prospective or randomized.22

One trial reported the aggregate results of many surgeons, each contributing a few of their early attempts with pneumatic retinopexy with understandably poor results.23 Several papers concluded the operation was less successful in pseudophakic eyes, but also noted that failed cases ultimately did well.24,25

Today, many surgeons remain reluctant to treat the simplest detachment with pneumatic retinopexy when the eye is pseudophakic. We agree that the single operation success rate is not as high in pseudophakic eyes but the procedure still works well in most cases and, if it does fail, no harm is done. Dr. Hilton and I subsequently published a paper addressing these adverse experiences and showed how most complications are avoidable.26

|

Pneumatic retinopexy is performed less often today for many reasons. More preoperative time is required to prepare and educate the patient; vitrectomy instrumentation is reliable; fewer fellows are adequately trained with scleral buckling; surgeons are economically punished for performing pneumatic retinopexy; and doctors are not responsible for the total cost of the intervention (including inevitable cataract surgery following vitrectomy).

In the very near future, I predict pneumatic retinopexy will become more popular. Surgeons will be compensated by their outcomes and resources they consume. Even if one assumes a 60-percent pneumatic success rate, pneumatic retinopexy is still more cost-effective than buckling or vitrectomy.

One cannot separate the surgeon from the surgery. Pneumatic retinopexy requires a trained eye to find the breaks, and an experienced surgeon to select the right operation and perform the pneumatic procedure correctly, which appears deceptively simple on the surface. It is especially important to perform a recue operation in a timely fashion. I continue to perform pneumatic retinopexy because it remains the best way to restore pre-detachment vision (See Figure 4).

Finally, for a trip down memory lane I suggest you visit

youtube.com, where you will find a short video of Dr. Hilton performing and narrating pneumatic retinopexy, by searching “

George Hilton pneumatic retinopexy.”

|

1. Ohm J. Uber die Behandlung der Netzhautablosung durch operative Entleerung der subretinalen Flussigeit und Einspiritzung von Luft in den Glaskorper. Albrecht von Graefe’s Archive for Ophthalmology 1911; 79:442-50.

2. Rosengren B. Results of treatment of detachment of the retina with diathermy and injection of air into the vitreous. Acta Ophthalmol AcND 1938;16:573-9

3. Hilton GF, Grizzard WS. Pneumatic retinopexy: A two-step outpatient operation without conjunctival incision. Ophthalmology 1986;93:626-641.

4. Dominguez DA. Cirugia precoz y ambulatoria del desprendimento de retina. Arch. Soc Esp Ottalmol 1985;48:47-54

5. Kreissig I. Clinical experience with SF6 gas in detachment surgery. Berichte der Deutschen Ophthalmologischen Gesellschaft 1979;76:553-60.

6. Lincoff H, Kreissig I. Application of xenon gas to clinical retinal detachment. Arch Ophthalmol 1982;100:1083-5

7. Boldrey EE. Beside intraocular gas injection for failed retinal detachment procedures. Proceeding of the Paul Cibis Club, St. Louis, 1979, pp 88-94.

8. Hilton GF, Kelly NE, Salzano TC, Tornambe PE, Wells, JW, Wendel RT. Pneumatic Retinopexy: A Collaborative Report of the first 100 Cases. Ophthalmology 1987;94:304-14.

9. Tornambe PE, Hilton GF, Kelly NF, Salzano TC, Wells JW, Wendel RT. Expanded Indications for Pneumatic Retinopexy. Ophthalmology 1988;95:597-600.

10. Hilton GE, Tornambe PE, Brinton DA, et al; The Complications of Pneumatic Retinopexy. Tr Am Ophthalmol Soc 1990;88:191-210.

11. Pneumatic Retinopexy, A Clinical Symposium. Edited by Paul Tornambe, MD & WS Grizzard, MD. DesPlaines, Ill.: Greenwood Publishing, 1989.

12. Tornambe PE, Hilton GF, Brinton DE, et al. The Pneumatic Retinopexy Clinical Trial. Ophthalmology 1989;96:772-783; discussion 784.

13. Tornambe PE, Hilton GF, Brinton DE, et al. A Two-Year Follow-up Study of the Multicenter Clinical Trial Comparing Pneumatic Retinopexy with Scleral Buckling. Ophthalmology 1991;98:1115-1123.

14. Poliner LS, Grand GG, Shoch LH, et al. New retinal detachment after pneumatic retinopexy. Ophthalmology 1987;94:315-318.

15. Freman WR, Lipson BK, Morgn CM, et al. New posteriorly located retinal breaks after pneumatic retinopexy. Ophthalmology 1988;95:14-18.

16. McDonald HR, Abrams GW, Irvine AR, et al. The management of subretinal gas following attempted pneumatic retinal attachment. Ophthalmology 1987;94;319-26.

17. Chan CK, Wessels IF. Delayed subretinal fluid absorption after pneumatic retinopexy. Ophthalmology 1989;96:1691-1700.

18. Yeo JH, Vidaurri-Leal J, Glaser BM. Extension of retinal detachments as a complication of pneumatic retinopexy. Arch Ophthalmol 1986;104:1161-3.

19. Runge PE, Wyhinny GJ. Macular hole secondary to pneumatic retinopexy. Case report. Arch Ophthalmol 1988;106:586-7.

20. Eckardt C. Staphylococcus epidermidis endophthalmitis after pneumatic retinopexy. Am J Ophthalmol 1987;103:720-1.

21. Steinmetz RL, Kreiger AE, Sidikaro Y. Previtreous space gas sequestration during pneumatic retinopexy. Am J Ophthalmol 1989;107:191-2.

22. Mulvihill A, Fulcher T, Datta V, Acheson R. Pneumatic retinopexy versus scleral buckling: A randomised controlled trial. Ir J Med Sci 1996;165(4):274-7.

23. Han DP, Mohsin NC, Guse CE, Hartz A, Tarkanian CN. Comparison of pneumatic retinopexy and scleral buckling in the management of primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Southern Wisconsin Pneumatic Retinopexy Study Group. Am J Ophthalmol 1998;126:658-68.

24. Ross WH, Lavina A. Pneumatic retinopexy, scleral buckling, and vitrectomy surgery in the management of pseudophakic retinal detachments. Can J Ophthalmol 2008;43(1):65-72.

25. Kleinmann G, Rechtman E, Pollack A, Schechtman E, Bukelman A. Pneumatic retinopexy: Results in eyes with classic vs relative indications. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120:1455-9.

26. Pneumatic retinopexy. An analysis of intraoperative and postoperative complications. The Retinal Detachment Study Group. Hilton GF, Tornambe PE. Retina. 1991;11:285-94. Review.

27. Tornambe PE. Pneumatic Retinopexy, The Evolution of Case Selection and Surgical Technique. A Twelve-Year Study of 302 Eyes. Tr Am Ophthalmol Soc 1997;95:551-78.