Presentation

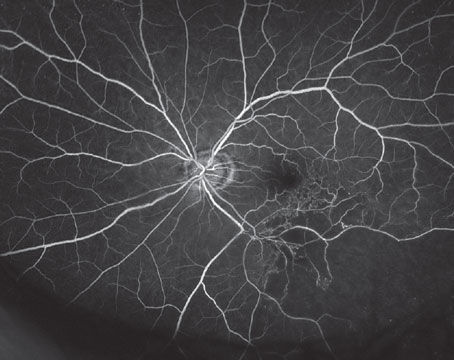

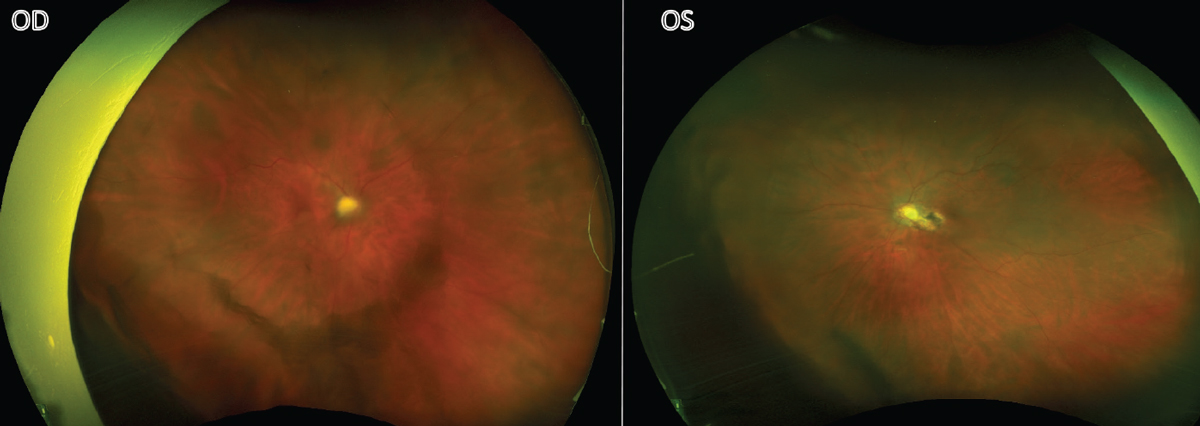

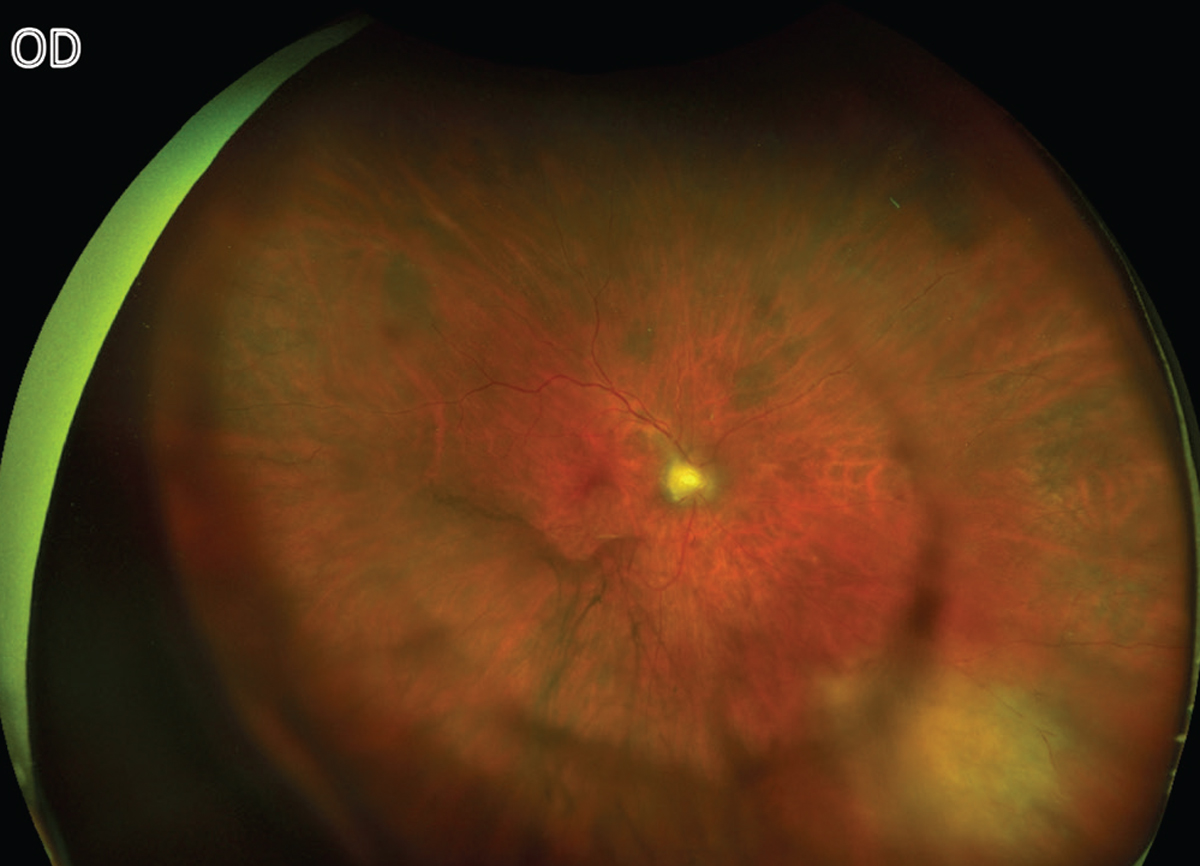

A 78-year-old Caucasian female was referred to uveitis clinic for further evaluation of perivascular sheathing and floaters in the right eye. She had a history of ocular toxoplasmosis in the left eye, confirmed by PCR of an aqueous sample, for which she received intravitreal clindamycin 10 years prior. Her visual acuity was chronically count-fingers in the left eye due to peripapillary and papillomacular involvement (Figure 1). Due to her monocular status, she was debilitated by her new-onset floaters in the right eye. She endorsed no pain or photophobia.

|

| Figure 1. Bilateral fundus photos taken at initial visit. |

Medical History

Her complex medical history included active chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), diverticulitis status post-colonic resection, hepatitis B, congestive heart failure and hypertension. Her medications included venetoclax (BCL-2 inhibitor), tenofovir, entecavir, carvedilol, lisinopril, prophylactic acyclovir, fenofibrate, cyclobenzaprine, omeprazole, lorazepam, gabapentin and duloxetine. Ocular history included bilateral cataract surgery several years prior and toxoplasmosis of the left eye as described above. She had no relevant family history. She denied cigarette smoking or drug use, and she drank one to two alcoholic beverages a week.

Exam

On initial presentation, visual acuity was 20/20 OD and CF OS. Pupils were equally round and reactive with no afferent pupillary defect. Intraocular pressure was 14 mmHg OD and 11 mmHg OS. The anterior exam was normal in both eyes, with no keratic precipitates, cell, flare or iris transillumination defects. Both PCIOLs were well-positioned in the capsular bag. The posterior exam was significant for 1+ vitreous cell and moderate vitreous debris OD, with no evidence of vasculitis and no lesions besides a choroidal nevus present in the periphery. The left eye had trace vitreous cells and an inactive chorioretinal scar sparing the fovea as seen in Figure 1.

What is your diagnosis? What further work-up would you pursue? The diagnosis appears below.

Work-up, Diagnosis and Treatment

|

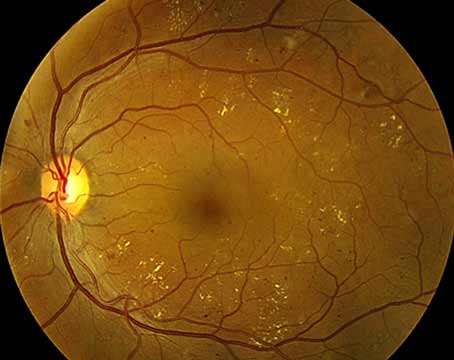

| Figure 2. The right fundus a month after sub-Tenon’s triamcinolone injection with new active lesion present inferonasally. |

At initial presentation, the differential included infectious (syphilis, Lyme, toxoplasmosis), inflammatory (sarcoidosis), neoplastic (lymphoma) or iatrogenic (biologic use) etiologies. It was suspected that the patient’s chemotherapy agent, venetoclax, might be associated with the ocular inflammation. Sub-Tenon’s triamcinolone 20 mg/0.5 mL was administered superotemporally OD.

One month later, the patient returned for follow-up and was found to have an area of inferonasal retinal whitening in the right eye (Figure 2). The peripheral lesion was fluffy white with creamy edges and severe vitritis. Visual acuity remained stable at 20/25+1 OD, although she complained of subjectively worsening vision. Fundus autofluorescence imaging showed hyperautofluorescence of the lesion OD, in contrast to the hypoautofluorescent scar in the left eye. Lab testing was pursued, with CBC only notable for mild thrombocytopenia (platelet count 134K) and CMP within normal limits. Serum ACE, Lyme, RPR, interferon gamma releasing assay (QuantiFERON Gold Plus) and Toxoplasma gondii IgG and IgM testing were negative. Given the inconclusive blood work, the decision was made to perform an anterior-chamber tap for PCR testing, which was negative for HSV-1/2, CMV and VZV, but positive for T. gondii (3,300 copies/mL). She was treated with sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (TMP-SMX) twice daily and intravitreal clindamycin 1 mg. She didn’t tolerate TMP-SMX, and thus was switched to azithromycin 250 mg/day.

|

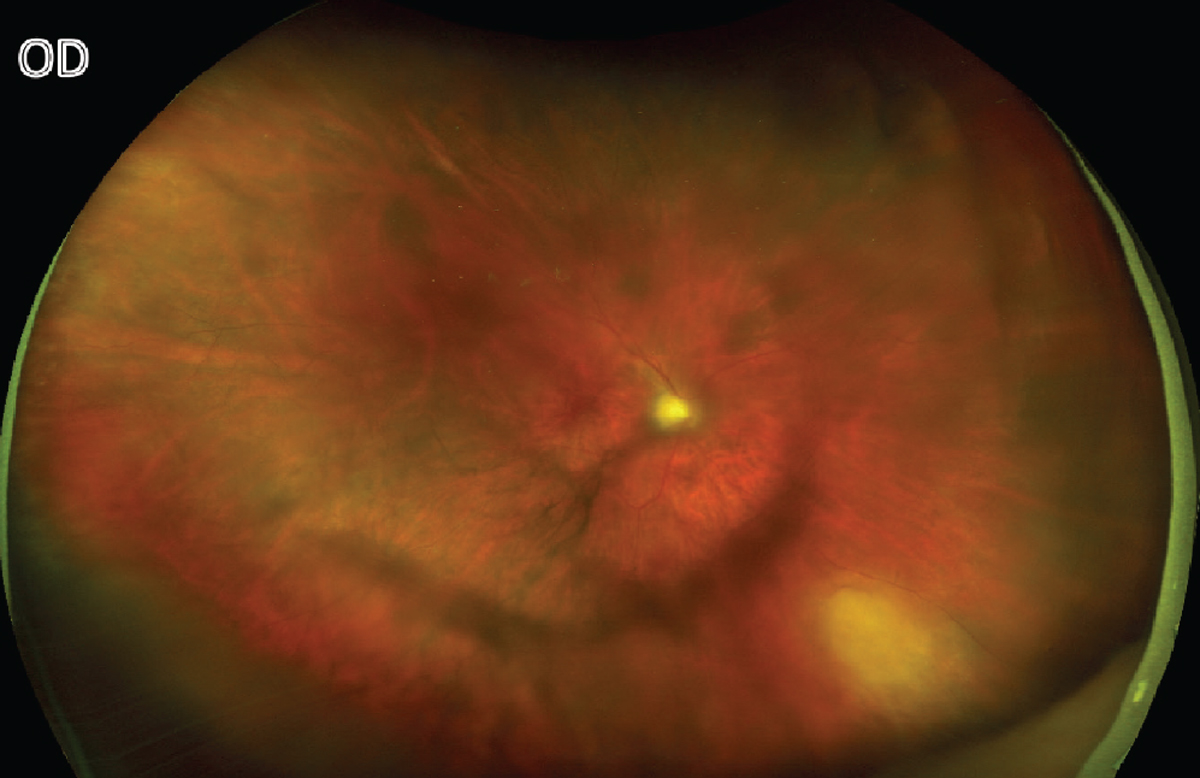

| Figure 3. A right-eye fundus photo two months after initial visit with improving inferonasal toxoplasma lesion. |

She returned a week later with persistent blurred vision and floaters but stable acuity. She was treated with prednisone 30 mg daily with a weekly taper. A month later, the lesion showed less active borders (Figure 3). This patient continued to be closely followed.

Discussion

In this case, a 78-year-old immunocompromised woman with prior ocular toxoplasmosis OS presented with new intermediate uveitis OD. She was treated with a sub-Tenon’s triamcinolone injection resulting in an acute worsening of symptoms and a new peripheral retinochoroidal lesion. This is an unusual case of ocular toxoplasmosis, given the initial presentation of intermediate uveitis, bilateral toxoplasmic involvement in a non-endemic region, and negative IgG and IgM serological testing with T. gondii DNA detected in the aqueous humor.

Typically, acute ocular toxoplasmosis presents as unilateral retinochoroiditis with the classic “headlight in the fog” appearance with fluffy white edges and haze due to vitritis.1 As seen in Figure 1, this patient’s ocular toxoplasmosis initially presented with vitritis but no visible lesion. Cases have been reported of infected individuals with transient episodes of intraocular inflammation, but the pathophysiology is unknown.1 Other signs of this protozoal infection can be anterior uveitis (granulomatous or non-granulomatous), satellite lesions, vasculitis and inflammatory ocular hypertension; our patient didn’t have any of these findings, however. Given the clinical picture with no visible retinitis, an inflammatory or iatrogenic etiology was higher on the differential and peri-ocular steroids were administered to preserve vision in a monocular patient. Even in immunocompetent patients, periocular steroid injections given for toxoplasmosis can lead to fulminant eye disease, particularly in those who haven’t received anti-parasitic therapy.2 In this patient, the sub-Tenon’s triamcinolone injection likely catalyzed the onset of the retinochoroiditis.

TMP-SMX or other antibiotic therapy may be used to control the parasites’ reproduction in the active phase while the patient is on topical and systemic steroids. Unfortunately, toxoplasmosis is incurable, as the bradyzoite form residing in tissue cysts doesn’t respond to antimicrobials. In most immunocompetent patients this infection is self-limited.3

Given the epidemiology of ocular toxoplasmosis, bilateral disease and reinfections are atypical in the United States. Although the seroprevalence ranges from 22.5 to 80 percent, increasing with age, the prevalence of infected individuals with ocular manifestations is estimated to be around 2 percent.4 In contrast, 17.7 percent of those infected in Brazil have evidence of toxoplasmosis affecting the retina. France similarly has a high prevalence of T. gondii infections with 67 percent of pregnant women being IgG positive.4 There are theories about what may cause the recurrence of toxoplasmosis, including trauma and hormonal changes, but immunosuppression is not thought to be a trigger.5,6 Our patient didn’t recall any inciting incident. Bilateral involvement is more likely in congenital toxoplasmosis infections versus acquired, but it isn’t considered a distinguishing factor in the diagnosis.7

This case brings to focus important differences in interpreting diagnostic testing for ocular toxoplasmosis for those who are immunocompromised compared with those who are immunocompetent. In an immunocompetent individual, a non-reactive IgG and IgM essentially rule out toxoplasmosis infections. A study in Brazil determined that a negative IgG serology has a 91-percent negative predictive value.8 In contrast, a positive IgG and IgM serum test indicates past or recently acquired infection, respectively, but doesn’t localize the infection to the eye.9 Our patient had CLL and was undergoing treatment with a BCL-2 inhibitor, both of which impair her ability to produce antibodies during infections.10,11 Therefore, she didn’t produce detectable immunological memory to the T. gondii infection in her left eye 10 years prior, which increased her likelihood of multifocal disease and reinfections. Given this patient’s atypical presentation and threat to her only functional eye, it was clinically justified to proceed with the more invasive anterior chamber paracentesis to ensure she was being treated appropriately.

PCR testing in ocular toxoplasmosis has lower sensitivity (36 to 55 percent) than in acute retinal necrosis (roughly 90 percent) and may vary according to the strain of the Toxoplasma organism.12 On the other hand, PCR testing has a 100-percent positive predictive value in ocular toxoplasmosis.13 Thus, a positive PCR test is diagnostic, but a negative PCR test doesn’t definitively rule out the disease. The use of other diagnostic tests, such as the Goldman-Witmer coefficient and immunoblotting, may reduce the risk of false-negative results;13 however, these aren’t commonly used in the United States.

Other investigators have suggested that combining PCR testing from both the aqueous and vitreous humor may increase the diagnostic yield in atypical cases of ocular toxoplasmosis in immunocompetent patients, in whom the yield from aqueous humor specimens may be substantially less than in immunosuppressed patients.12,14 The low DNA detection rates in immunocompetent patients suggest that there is a low parasitic burden in the aqueous and that the onset of symptoms and inflammation could be driven by a robust immune response rather than the activity of the parasite.14 Due to the detectable PCR load (3,300 copies/mL) and classic retinochoroidal lesion after steroid administration, our patient didn’t require further testing.

In conclusion, ophthalmologists should have a high clinical suspicion of atypical presentations of toxoplasmosis in those who are immunocompromised, as the disease could take on an aggressive course. When in doubt about the diagnosis with a potentially vision-threatening disease process, it is important to obtain aqueous testing, as serum IgG and IgM may not be sufficient in those who are immunocompromised.

1. Holland GN, O’Connor GR, Belfort R, Remington JS. Toxoplasmosis. In: Pepose JS, Holland GN, Wilhelmus KR, eds. Ocular Infection and Immunology. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book, 1996:1083-1223.

2. Holland GN, Lewis KG. An update on current practices in the management of ocular toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol 2002;134:1:102-114. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01526-x

3. Kalogeropoulos D, Sakkas H, Mohammed B, et al. Ocular toxoplasmosis: A review of the current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. Int Ophthalmol 2022;42:1:295-321.

4. Holland GN. Ocular toxoplasmosis: A global reassessment. Part I: Epidemiology and course of disease. Am J Ophthalmol 2003;136:6:973-988.

5. Holland GN, Engstrom RE, Glasgow BJ, et al. Ocular toxoplasmosis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1988;106:6:653-667.

6. Morhun PJ, Weisz JM, Elias SJ, Holland GN. Recurrent ocular toxoplasmosis in patients treated with systemic corticosteroids. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa) 1996;16:5:383-387.

7. Petersen E, Kijlstra A, Stanford M. Epidemiology of ocular toxoplasmosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2012;20:2:68-75.

8. Murata FHA, Previato M, Frederico FB, et al. Evaluation of serological and molecular tests used for the identification of Toxoplasma gondii infection in patients treated in an ophthalmology clinic of a public health service in São Paulo State, Brazil. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2019;9:472.

9. Garweg JG. Ocular toxoplasmosis: An update. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd 2016;233:4:534-539.

10. Arruga F, Gyau BB, Iannello A, Vitale N, Vaisitti T, Deaglio S. Immune response dysfunction in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Dissecting molecular mechanisms and microenvironmental conditions. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:5.

11. Bose P, Gandhi V. Managing chronic lymphocytic leukemia in 2020: An update on recent clinical advances with a focus on BTK and BCL-2 inhibitors. Fac Rev 2021;10:22.

12. Bourdin C, Busse A, Kouamou E, et al. PCR-based detection of Toxoplasma gondii DNA in blood and ocular samples for diagnosis of ocular toxoplasmosis. J Clin Microbiol 2014;52:11:3987-3991.

13. Fekkar A, Bodaghi B, Touafek F, Le Hoang P, Mazier D, Paris L. Comparison of immunoblotting, calculation of the Goldmann-Witmer coefficient, and real-time PCR using aqueous humor samples for diagnosis of ocular toxoplasmosis. J Clin Microbiol 2008;46:6:1965-1967.

14. Garweg JG, de Groot-Mijnes JDF, Montoya JG. Diagnostic approach to ocular toxoplasmosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2011;19:4:255-261.