When surgeons sit down and list the pros and cons of adopting femtosecond cataract surgery in their practices, one item always falls squarely in the “con” section: efficiency. Both the learning curve and the extra steps of the procedure slow you down, say many surgeons. As they grapple with ways to make it work logistically, a solution that’s been bandied about is the use of optometrists to operate the device. “If the procedure really is that automated, why not?” some surgeons wonder. However, to other surgeons, the question is not that simple: “I don’t understand how you’re going to compromise care [to save] three to four minutes,” many say. And with that, a new debate has begun, over both patient care for cataract surgery and the possible long-term ramifications of ceding even some of the steps of cataract surgery to optometrists. Here, experts from all sides of the discussion weigh in.

The Need for Efficiency

Surgeons say that, at least when you first install a femtosecond cataract laser, it can add at least eight to 10 minutes to each case. Delegating the operation of the laser to someone else, with the surgeon coming in at the end to open the capsulorhexis, aspirate the nucleus, insert the lens and close, would seem like a valid strategy to avoid losing time.

|

“The femtosecond laser, at least in this iteration, is less efficient than manual cataract surgery,” says Bill Wallace, practice administrator for Wallace Eye Care in Alexandria, La. “It takes more time, it adds a step. And cataract surgery has become a very efficient procedure. Surgeons will be looking for ways to maintain that efficiency and will be expected to, because they have a limited amount of time that they can be in their operating facilities.” Mr. Wallace adds that the idea of using physician extenders isn’t new. “What we’re seeing in a lot of other specialties, even in our area, is that physician’s assistants and nurse practitioners are very involved, not just in the clinic but also in surgery,” he says. “It’s not uncommon for PAs to assist surgeons, making incisions, suturing, that kind of thing. The idea that ophthalmology will be immune to this is probably not sound thinking. I don’t think it’s unusual to think that someone other than the primary surgeon might be driving the femtosecond laser ... In that vein, I think we’re lucky to have optometrists, who have specialized eye-care training and maybe even a little more training in their field than a PA or NP would traditionally have.”

Derek Cunningham, OD, director of optometry for Dell Laser Consultants in Austin, Texas, has helped train surgeons to use the LenSx, and says the debate about whether the surgeon really needs to run the device has existed since the beginning. “When a surgeon is trained on the device, he watches a technician do numerous cases before he takes over the reins. So what’s the difference?” he says. “Some of the surgeons feel that if you’re going to have a technician run it, why not have an optometrist run it? The optometrist has a lot better understanding of pathophysiology, anatomy and things of that nature, than a technician.”

Some eye-care practitioners, however, say that the idea that the LenSx always slows you down may not be accurate. They say that, over time, the surgeon gains proficiency with the device and the surgery time actually decreases.

“The slowdown to our surgeries was certainly true six to nine months ago,” says Alan Crandall, MD. He and his partner Robert Cionni, MD, were the first surgeons to purchase a LenSx in the United States. Over the past year, they’ve performed 1,000 cases with it. “It also depends how you’re set up. Bob Cionni and I have the femtosecond in one room and two other operating rooms. Originally, when we started and were learning the docking procedure and the other steps, it added eight to 10 minutes to the case, which was like almost adding another case. Now, we’re averaging an extra two to 2.5 minutes. As the software improves, it will become more efficient, too. For example, the capsulorhexis now takes one-third of the time it took to do six months ago. If you have one OR, though, it’s going to be an issue. In that case, you have an issue with logistics. I think that could slow down the day.”

Looking at it from another angle, it’s possible it might even be more efficient for one person to do the entire procedure. “When you think about the very short period of time it takes from when you start the procedure and then follow through the rest of it, you’re talking about a handful of minutes,” says Stillwater, Okla., optometrist David Cockrell, secretary-treasurer of the American Optometric Association. “It would seem to me to not be efficient to be changing in mid-stream. It takes longer to get out of the way and let the other person sit down than it does to just finish the procedure.”

The Patient Care Perspective

Whether using an optometrist to operate the laser is more efficient or not, the American Academy of Ophthalmology and many surgeons don’t think anyone other than a surgeon should perform cataract surgery.

“The academy considers the laser to be a surgical instrument,” says Sun City West, Ariz., surgeon Daniel Briceland, the AAO’s secretary for state affairs. “To perform surgery, you have to understand all the principles and foundations of surgery in general. You can’t cut and paste some parts of a procedure out. Cataract surgery is cataract surgery, whether you do part of it with a femtosecond laser or a knife. You have to be aware of the complications that can occur at any time during the procedure.”

|

“In my opinion, the issue here isn’t MDs’ and ODs’ territory, or politics, it’s a medical quality-of-care issue,” Dr. Wang says. “The same doctor has to perform both the LenSx portion and the manual portion of the surgery, because the success of, or any problem with, the LenSx part has important consequences for the lens extraction.”

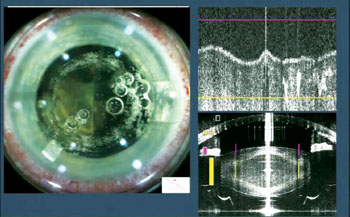

Dr. Wang offers several examples: “During the capsulorhexis creation, sometimes bubbles prematurely escape into the anterior chamber,” he says. “When this happens, subsequent laser shots may not be able to get through and reach the anterior capsule, which could result in an incomplete capsulorhexis. This means that during the manual portion of the surgery, you need to be careful when teasing out that capsulorhexis edge because there are tags in there, and you could cause a radial tear. You can only get that information by watching the LenSx portion of the capsulorhexis yourself, because once it’s finished and the bubbles have escaped, you have no idea where the earlier bubbles blocked the pulses.

“Also, sometimes during LenSx docking and centration, lens tilt occurs, which results in the anterior and posterior LenSx cut planes not being parallel relative to the anterior lens surface,” Dr. Wang continues. “When this occurs, the surgeon has to make a determination of how deep the laser should go during lens softening, because if the lens is tilted, you may not want to go too deep because the laser area may intersect the posterior capsule. Or, in other cases, I may notice that the lens is very thick. In that case, I may want to place the laser energy a bit more posteriorly to make sure I fragment the central portion. In a softer lens, I don’t need to go that deep and risk damaging the posterior capsule. But whatever the case, this obviously has tremendous impact on the second group of manual steps, because the second operator—the extraction person—would need to know how thick of a layer the first person left. If the laser went very far and the posterior uncut layer is very thin, you could easily cut the posterior capsule. This information is absent if the extraction operator never sees the LenSx in action.”

Dr. Cunningham, however, thinks such issues will be addressed as the technology advances. “There’s some validity to having the same person do each step,” he says. “That’s more or less based on today’s technology. Right now, you have an OCT that gives you a picture. Then the procedure starts and you don’t know exactly what happened until the procedure’s done because the OCT isn’t running during the procedure. With some of the newer lasers that are coming out, there will be real-time OCTs that will give an intraoperative view of the process as it’s happening, and you’ll have that data recorded.”

A Question of Training

Both sides of the debate agree that, if an optometrist is allowed to perform laser cataract surgery, he’ll need some kind of training. What they don’t agree on, however, is just how much.

Dr. Cunningham doesn’t think an optometrist would need much more education than training by the ophthalmologist he works with. “The comprehensive education that an MD and an OD go through to understand anatomy is relatively similar,” he says. “Where a surgeon really separates himself is through his residency and his understanding of how the anatomy of the eye works with regard to intraoperative procedures and complications. There are plenty of optometrists right now who work very closely with the LenSx laser at the centers that have it. Someone like myself, what I do all day, every day, is provide post-surgical or peri-surgical care. I used to be in a group practice where I’d see postops from four or five surgeons non-stop. In one year, I’d see more postops than some of these providers would see in 10 years, because I’d be seeing everyone. No, the education wouldn’t change. The education would be very dependent on the practice’s MD and his motivation to get the optometrist to do it.”

Dr. Wang says that, regardless of his title, someone who wants to do femtosecond surgery should undergo a curriculum of education and training that’s of sufficient rigor, vetted by an objective third party. Hearing it described, his proposal sounds similar to a surgical residency. “This [proposed curriculum] really wouldn’t qualify optometrists to do the surgery,” says Dr. Briceland, “because what you’re actually saying is they can do it as long as they want to go to medical school and through residency—but they don’t want to do that. To perform surgery, it comes down to the educational process that allows for one-on-one observation of the student, and training in multiple settings and situations in patients with considerable disease. Residents ultimately spend around 17,000 hours in this training. That’s the standard the American health system puts forth as the requirement for surgery.”

A Slippery Slope?

Behind the questions of efficiency and patient care, looming in the background is the fear, real or imagined, that allowing an optometrist to perform laser cataract surgery will eventually lead to him doing the entire procedure.

“Without a doubt, there’s an optometric agenda,” says New York City-based glaucoma surgeon Andrew M. Prince. “The agenda is to ultimately be equal to ophthalmologists with regard to being able to perform all eye-care procedures, including surgery. And while that started with using diagnostic drops ... it’s now moving toward lasers and surgery. The problem is optometry as a profession has sought these expanded abilities via legislative mandate without undertaking and completing the corresponding required ophthalmic education and training, and what’s at risk is patient safety and the quality of eye care.

“Femtosecond cataract may make for an easier foray into doing intraocular surgery,” Dr. Prince continues. “To be able to say, ‘We don’t use a scalpel, we don’t want to use a scalpel at all on patients,’—well, you don’t have to use one if you do this. It’s going to make semantics more important, and I think the femtosecond is going to be used against what we should be defending: surgery by surgeons.”

Dr. Cockrell, however, disagrees to an extent. “I don’t foresee [optometrists doing the entire cataract procedure] at any point in the near or intermediate future,” he says. “That’s not something optometry currently trains to do, or advocates wanting to do in any state. We’ve never pushed for [the invasive intraocular surgery part of cataract surgery] in any state, even Oklahoma. Even though we do different glaucoma surgeries such as SLT, that’s different than what you are talking about there.”

Dr. Cunningham feels similarly. “I truly believe, as do virtually all optometrists in positions of influence in state legislation, that that’s a step that’s moving toward extensive amounts of continuing education,” he says. “The best avenue for optometrists to do that right now is to go to medical school.” REVIEW