Bellwether shifts in procedural volume, practice patterns and profitability brought on by COVID-19 have prompted many ophthalmologists in private practice to rethink when and how they will walk away from their life’s work. Old assumptions have faded in the minds of aging practitioners as they explore future opportunities. Other physicians are exploring mergers with bigger practices and selling to private equity firms.

The need has never been greater for updated insights on valuating your practice, understanding the current practice-sale market, marketing your practice to ideal buyers and stepping down as an employee or independent contractor before making a graceful and worthwhile exit from the practice you’ve sold.

In this report, experts offer insights on their experiences, and advice on how you can respond wisely to today’s unexpected and, to some extent, unprecedented challenges.

Exploring Your Options

Although COVID-19 is stirring thoughts of career change, exit strategy choices remain the same, according to John Pinto, founder of J. Pinto & Associates, an ophthalmic practice consulting firm in San Diego. He summarizes each option:

1. Winding down and closing. “We see this approach when there are no likely buyers for your practice,” Mr. Pinto observes. “Or when you’ve exhausted all opportunities to divest your practice. This happens a lot in the rural Midwest and areas where it’s difficult to recruit doctors. A significant number of small, rural practices are closing each year, as boomer-age doctors fail to find buyers. If you can’t find a buyer, you may have to simply wind down operations and sell your tangibles for salvage value.” To avoid abandoning your patients, he adds, you can provide them with their charts (if they want them) or send the charts to practices where your patients ask the charts to be sent, which Mr. Pinto says is routinely done. You may also store the charts or convey them to a colleague who’s willing to act as a custodian or who may be able to care for your patients, depending on their interests and needs. “Laws vary state by state on how to do this,” says Mr. Pinto. “It would be best to contact your state medical society and discuss your options with your attorney.”

2. Traditional approach. “In this familiar model, you hire a new partner-tracked associate a few years before retiring,” he says. “In a larger practice, you’ll see a revolving carousel of doctors at different ages—a few beginning their careers, a few close to retiring and most in their mid-careers. We see this approach in the most-stable practices, which are now on a third generation of doctors. However, fewer practices are falling into this category.”

3. Sell to a “near-lying” practice. A near-lying practice might belong to a friendly colleague or nominal competitor. “Most practices are worth more to near-lying practices than they are to doctors just getting out of training,” Mr. Pinto says. “Certainly, if you’re ready to sell, it’s reasonable to look around your neighborhood to see who might like to take over.”

4. Sell to a health-care system. These opportunities are rare because ophthalmology, typically detached from acute-care centers, is not an admitting specialty. “But some local health-care systems are building eye-care departments, so one might just be interested in your practice,” he adds. “Generally, though, the payment you’d receive for this sale would be about half of what you’d receive from a doctor-to-doctor sale of your practice.”

|

5. Sell your practice to a private equity firm and stay on board. “Payment for your practice is as much as twice what you’d receive from a doctor-to-doctor transaction,” says Mr. Pinto. “It can be like manna from heaven if you’re nearing retirement, allowing you to extract as much value from your practice as possible. The downside is you’ll have less control over administrative and clinical areas. For our mid-career clients, we find that the benefits are somewhat more equivocal.”

6. Merge your practice with a larger, compatible practice. In this scenario, you may transition from owning 100 percent of your practice to a fractional share of the larger practice. “It may make sense for docs under certain circumstances—if you’re in your 50s and don’t know if you have five or 10 years left before retiring, for example,” says Mr. Pinto. “You might be getting fatigued by the administrative burden, or you might be having problems getting contracts that provide access to patients.” He notes that this option can be professionally satisfying, providing access to colleagues “down the hall” when you need a second opinion, for example. It also relieves administrative burdens.

7. Retire from your practice but retain ownership and run it like a business. “This is rarely done, but I think we’ll see more of this going on,” says Mr. Pinto. “Under this scenario, your practice would continue as a business after you retire—or even after you expire. Your wife or other family members can take over when you’re gone and run it almost like a passive investment.” He says the model can be difficult to manage because you need to find cooperative doctors willing to work for a controlling outside doctor—and eventually for your family. “Not many doctors will go along with this, but it can work for an owner in a larger market, where it’s harder for younger doctors to get jobs,” says Mr. Pinto.

Even though each of these succession options remains viable, Mr. Pinto and other experts say you’ll need to fine-tune and possibly overhaul your current practice exit plans to best position yourself in the future.

|

“The anxiety among ophthalmologists now is on steroids, if that makes sense,” says Craig N. Piso, PhD, of Piso & Associates, a psychologist and organizational development consultant with a focus on practice management in ophthalmology. “The pandemic, economy, unemployment and other factors are pulling doctors away from their usual laser focus on what they do well. They’re trying to determine what their futures might look like. I’m doing a lot of consultations.”

What’s Going On?

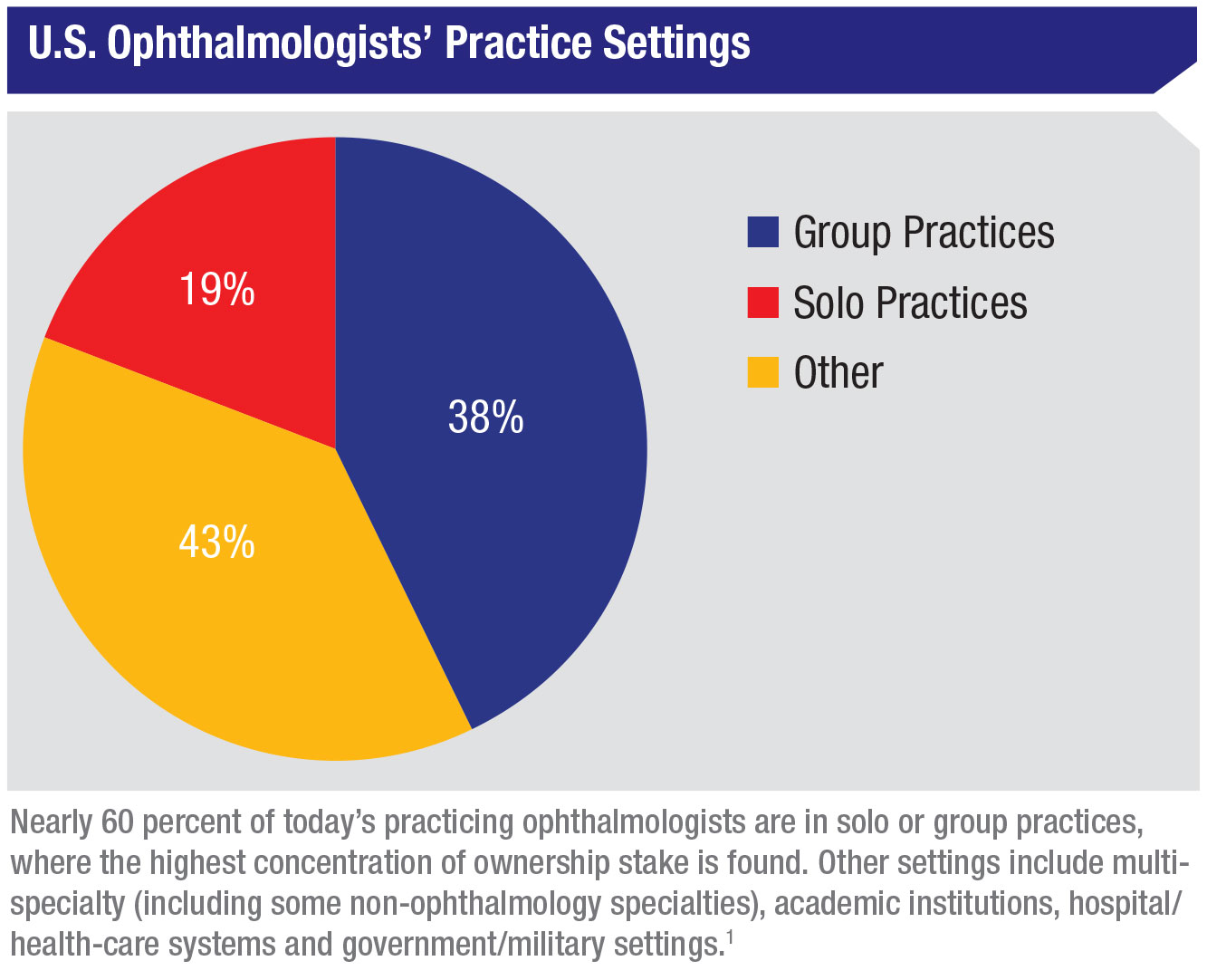

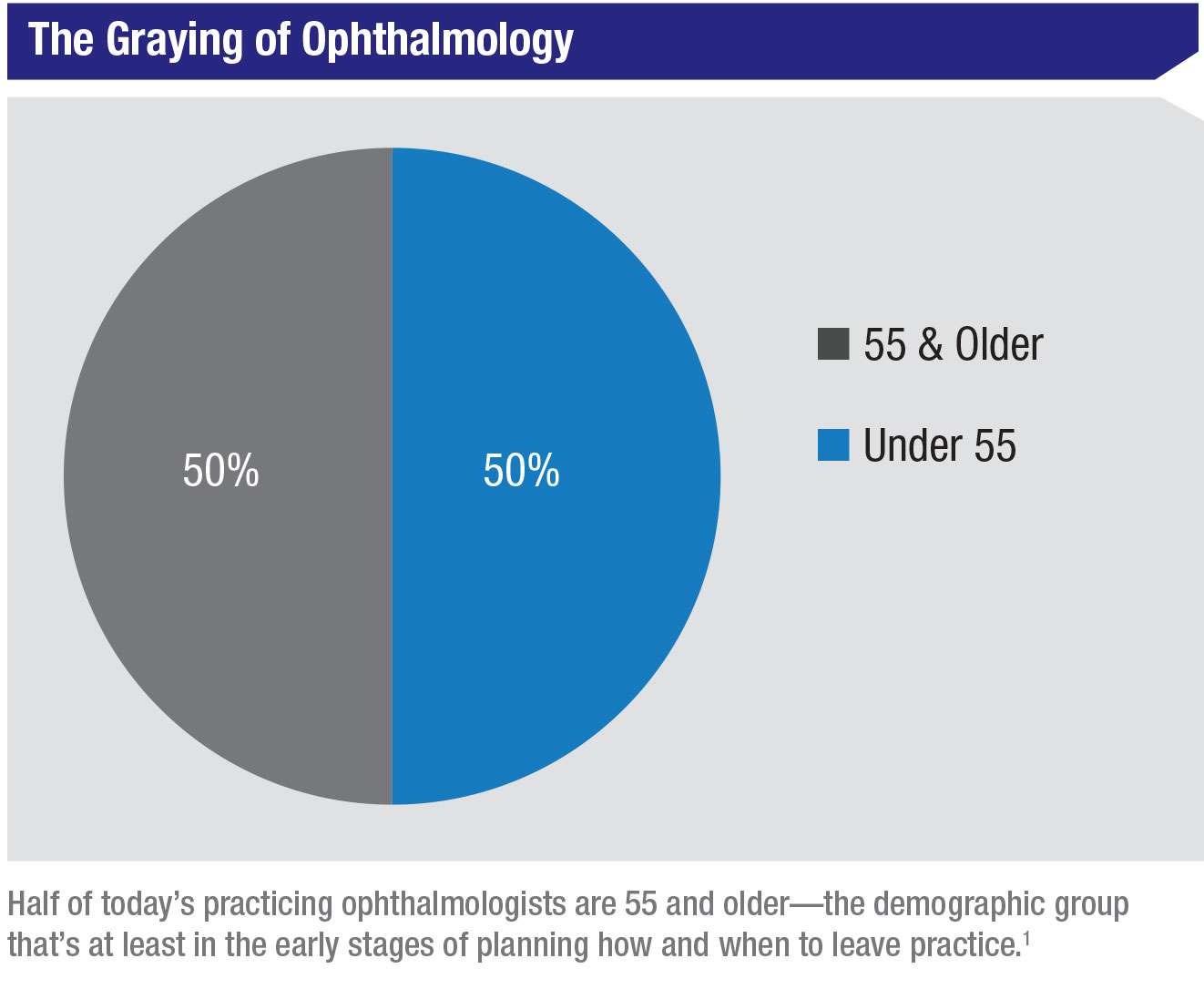

According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology, 50 percent of the 18,550-plus respondents to the most recent AAO membership survey1 are 55 years old or older—the demographic group that’s at least in the early stages of planning how and when to leave practice. A total of 57 percent are in solo or group practices, where the highest concentration of ownership stake is found.

|

“Exit strategies are typically well thought out and flow to a certain rhythm,” says Bruce Maller, founder and CEO of BSM Consulting, Incline Village, Nevada. “But the pandemic has changed the thinking of a lot of practitioners, causing them to consider different succession paths. Practices were severely disrupted when they were shut down by COVID-19 for two to three months. Of course, many have recovered, many are even operating at pre-shutdown levels. But even the recovery has been spotty, depending on where you practice and on a lot of local and regional dynamics.”

Mr. Maller sees “an overarching reassessment by practitioners” everywhere. “They’re asking themselves, ‘How do I want to plan my future? How does the pandemic affect us? Does it affect us to the extent that we should re-evaluate future succession options?’ ” he says.

Mr. Pinto notes that practices that had low profit margins before the pandemic have been hardest hit and are now burdened by uncertainty.

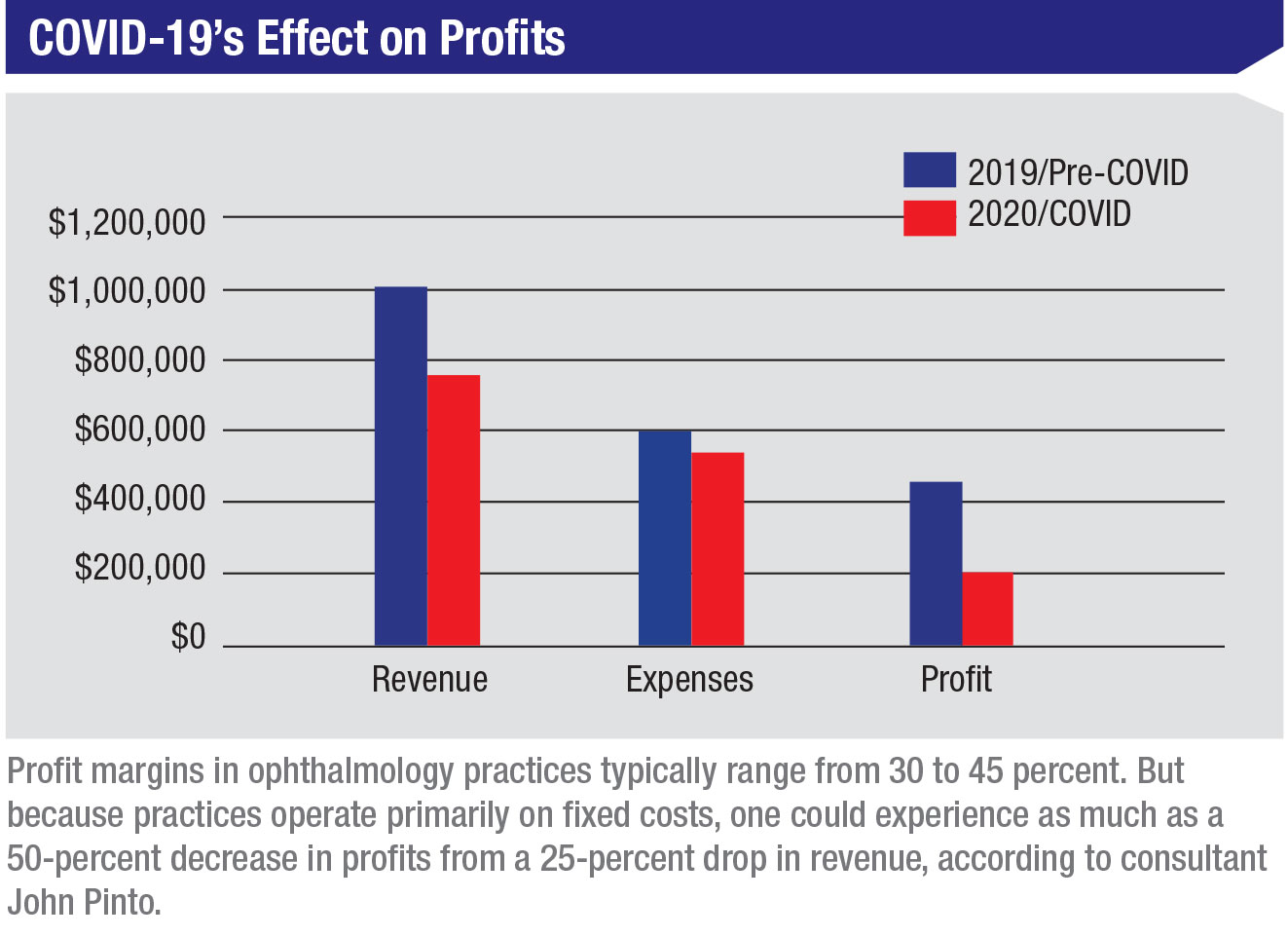

“All they had to do was modestly decrease revenue and it caused a leveraged impact on the bottom line,” he observes. “Profit margins in ophthalmology practices typically range from 30 to 45 percent. But because practices operate primarily on fixed costs, one could experience as much as a 50-percent decrease in profits from a 25-percent drop in revenue. (See COVID-19’s Effect on On Profits on page 51.) As Warren Buffet said, ‘You don’t find out who’s swimming naked until they drain the pool.’ In 2019, lots of practices appeared to be fairly vibrant. All it took was a little draining of the revenue pool, and those doctors were left naked, if you will.”

Like Mr. Maller, Mr. Pinto has found in his consulting work that some practices have rebounded well despite continuing patient flow reductions needed to keep waiting rooms safe and to meet other time-consuming safety requirements during visits. “Nothing has surprised us about some practices that have sailed smoothly through this pandemic year,” says Mr. Pinto. “These practices are a little smaller, so they can move faster. They have great MD/lay leadership and have a strong command of data. They could see what their capital access requirements were and where they needed to trim expenses. Also, some offices in rural areas have practiced social distancing as part of their culture for generations. These areas’ populations are less affected by COVID-19, so patients are less fearful about getting back to the doctor.”

How to Valuate Your Practice

Mark E. Kropiewnicki, Esq., LLM, an attorney with Health Care Law Associates and a consultant with the Health Care Group, both in Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania, says efforts to strengthen or at least maintain your bottom line are critical as you prepare to exit private practice by selling your practice.

“Profitability is a critical component of your practice valuation, which you want to be as high as possible,” says Mr. Kropiewnicki, who works on practice sales and purchases, as well as practice valuations, new-doctor employment agreements, buy-ins, pay-outs and income-division arrangements.

If you’re preparing to sell your practice, now is the ideal time to arrange for a valuation, being mindful that it will need to hold up to scrutiny and be flexible when negotiations over a sale ensue. A number of different types of valuation may be used, including the market-value (comparable sales) method, discounted cash flow method, multiple of earnings method and capitalization of earnings method. The type of valuation method most used by Mr. Kropiewnicki, as described below, includes an assessment of hard assets and goodwill values—only because accounts receivable are not sold in most practice sales.

Considerations include:

• Hard assets, including equipment, leasehold improvements, supplies and software. After eliminating items of marginal value, personal items and assets no longer in use, Mr. Kropiewnicki advises you to depreciate the value of countable depreciable items based on an average lifespan of 10 years—while maintaining a floor of 20 percent of original cost. For example, a $10,000 piece of equipment that you’ve owned for five years would be worth 50 percent of $10,000, or $5,000. If you’ve owned the equipment for 15 years, the value would be the floor value of $2,000. For supplies, such as drugs or optical frames, you would claim 1/12 or 1/6 of their yearly cost, depending on whether you keep one or two months worth of inventory. Or you’d do an inventory count and multiply that count by the current costs of the items.

• Goodwill is a benchmark value, based on comparable sales. “This approach would be similar to pricing a house,” except you’re considering the sales of comparable practices, according to Mr. Kropiewnicki. The goodwill encompasses the overall value of the ongoing concern, including charts, phone number, website, practice name, staff, seller’s endorsement of buyer and seller’s restrictive covenant. He notes that sellers and their brokers, attorneys, accountants or consultants may base their practices’ goodwill value on a percent of gross revenue. One such percent is provided by the Goodwill Registry, the self-described largest database of health-care practice transactions in the country, published by the Health Care Group. The Goodwill Registry’s average goodwill percent is based on the goodwill values of the reported transactions divided by the yearly collections of ophthalmology practices across the country.

The Registry’s current goodwill percent for ophthalmology practices includes a 10-year average of 30.82 percent, applied to the gross income of a practice to determine the goodwill value of an average practice.

For example, a practice that grosses $1 million should have a goodwill value of about $308,200. Added to $100,000 in hard assets and supplies, the owner of a practice might expect to sell the practice for $408,200. “But this goodwill value would be an average,” Mr. Kropiewnicki emphasizes. “Your practice’s goodwill total derived from this formula should be adjusted up or down according to good and bad features.” Good features could include high profits, ideal location, modern facilities, moderate competition and a good mix of payers. Bad features could include low earnings, an undesirable location, heavy competition and lack of access to desired patients because of closed health-insurance panels.

Finding the Right Fit

Marketing your practice for sale successfully depends more on your ability to target buyers, than on the outreach you may have used to develop referral networks and attract patients in the past. “The buyer will be a specific ophthalmologist or group that, under specific circumstances, has a need to seek out what your practice offers. You could be limited to young doctors in your area or organizations with a strategic interest in moving into your area, perhaps even using the office as a satellite location,” says Mr. Kropiewnicki, who will present a lecture titled Exit Options for the Senior Solo or Sole Practice Owner at the virtual AAO 2020 meeting this month. “You may also identify a friendly competitor from a neighboring town who wants to take over. Besides communicating your needs to trusted colleagues in the greater ophthalmology community, you could seek interested parties through the AAO or American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery, or you could advertise through these and other societies or professional publications.”

|

Says Mr. Pinto: “The overwhelming majority of small private practices are either sold to young doctors joining the practice or to local competing colleagues. Larger practices are attracting considerable private equity interest. Very, very few practices are sold via a practice broker. Most transactions emerge from direct seller contact with prospective buyers.”

When considering a potential sale, expert advice will be needed to structure agreements based on practice valuation, stock or asset values, payment terms, transition of ownership, implications for your practice’s staff, property rental or ownership, accounts receivable, tax considerations and other factors.

Another major consideration in all sales is the potential after-sale employment of the seller as a part-timer or at a reduced capacity, according to Mr. Pinto. “Practice buyers often prefer the seller to stay on for months to years to help transition the practice,” he says. “The arrangements are negotiated at the same time that the practice sale is organized. A typical scenario in general ophthalmology is for the owner to be paid plus or minus the amount of net collections.”

Setting aside important details on an assortment of issues, Mr. Kropiewnicki outlines common arrangements that you can use to attract an interested ophthalmologist or group of ophthalmologists: (Note: These arrangements don’t involve sales to private equity companies, which he notes aren’t typically interested in purchasing small practices.)

• Sale to an associate. This transaction, involving a one- to 12-month transition, involves cash and notes paid for the practice under a stock or asset sale. One typical arrangement is that you, as the seller, would work for a negotiated period after the sale as an employee or independent contractor before retiring, usually in one year (typically preferred by the buyer) or three to five years (typically preferred by the seller). If you’re selling to an associate who is already part of your practice, a sale can earn a high value. But you may need to finance most or all of the purchase price and feel comfortable with the transition terms.

Bringing on an associate for an eventual buy-in can be your most lucrative doctor-to-doctor sale option. “But that arrangement takes a long time,” notes Mr. Kropiewnicki. “Six to 10 years could pass: Your associate has to finish an initial employment of 24 to 30 months, and then would begin a buy-in process that could take four to five years.” He also notes the relationship could be strained by differences of opinion on fees and matters big and small or, worse, the departure of the associate before the sale is completed. “This is still the most commonly used model, however,” he notes.

• Sale to a competitor. This transaction, again typically taking one to 12 months, can also result in a high value for your practice. The competitor usually doesn’t need you to finance any of the purchase price and often accommodates your desire to continue practicing after the sale, perhaps at a reduced capacity—such as providing only medical care—for a period of years.

• Merging with another practice. Mr. Kropiewnicki says solo practice owners aren’t likely to attract many offers to merge with another practice. If such a possibility should materialize, however, the transition would typically involve a one- to six-month period. You shouldn’t expect to benefit from a stock or asset sale, he adds; instead, you’d continue as an owner with a partnership interest in the practice. Under such an arrangement, you can negotiate a buy-out when you’re ready to retire. The buy-out amount will depend on what the owners of the merged practice have mutually agreed to pay. There’s the potential for a high-value yield for you at that time.

• Doing nothing. “This can be the comfortable decision,” says Mr. Kropiewnicki. “You know what your life will look like. You could ease your workload and stress by dropping surgery when you’re ready to do so.”

Concerns with doing nothing are that you’re still exposed to reimbursement cuts, overhead increases, regulatory requirements and other practice challenges, however.

When you’re ready to sell, the value of your practice will be lower, based on reduced earnings. “It’s important to remember that cutting back or dropping surgery will hurt the value of your practice,” says Mr. Kropiewnicki, who notes that your health could also decline, further compromising the viability of your practice. “If you have an interested buyer for your practice, I would regard it as a bird in the hand and try to work out a deal,” he advises.

|

A Good Time to Sell?

Mr. Maller points to one dramatic example of COVID-19-related volatility in the practice succession space.

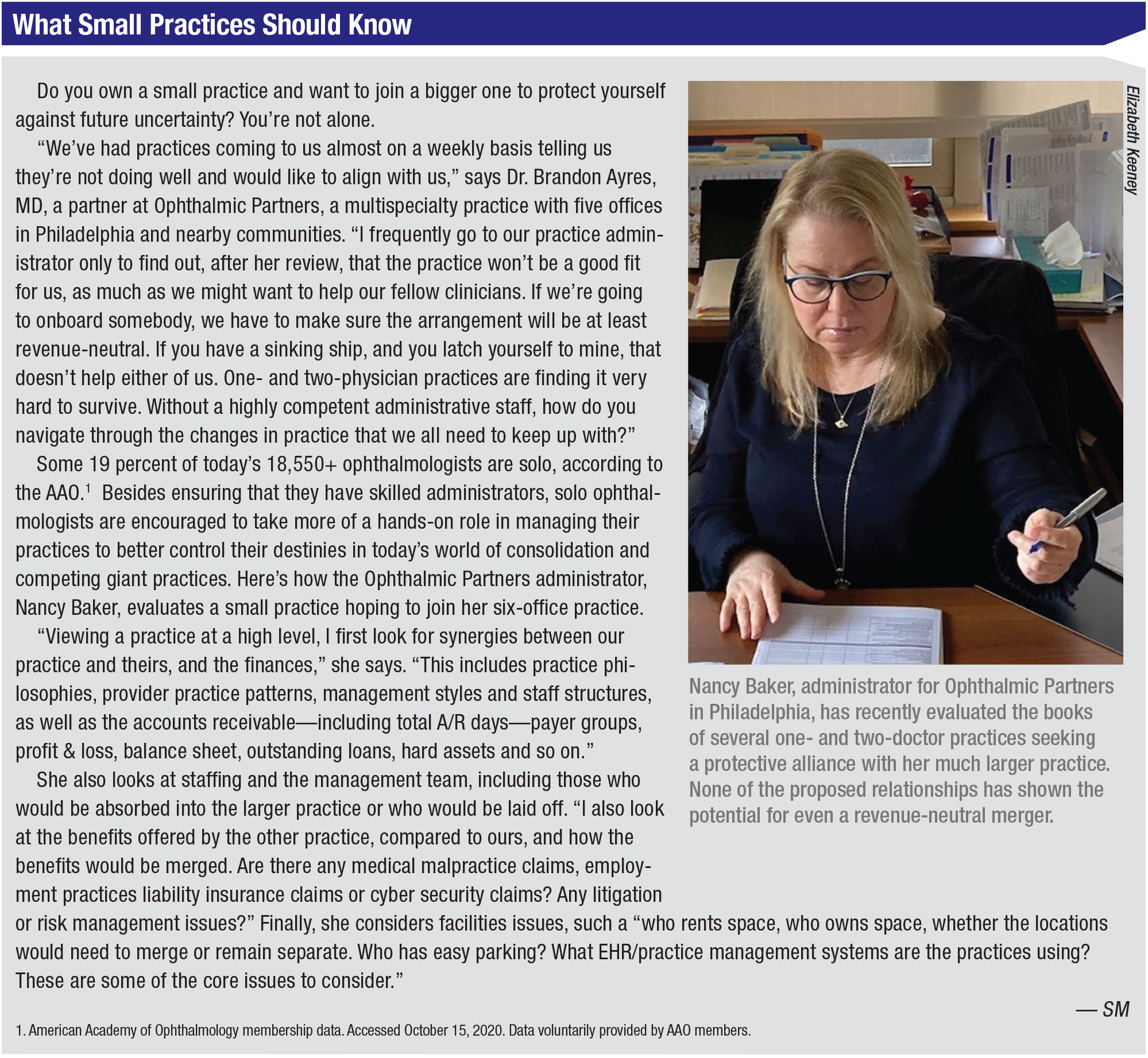

“I was representing more than 15 practices in potential sales to private-equity-backed ophthalmic platforms,” he says. “Then one day, in middle of March, it all came to a screeching halt. We were thinking the buyers wouldn’t return to the market until late this year or into 2021,” says Mr. Maller. “By late May through July, however, virtually every buyer was back in play. My universe of potential sales has now grown from 15 to more than 200. Owners of private practices feel that being part of something larger is going to provide security for their futures. They’re willing to give up control to join a group that will help them weather another storm.”

Other ophthalmologists, wary of corporate control, want to join larger private practices, according to Mr. Maller. Whether seeking more security from private equity or a larger private practice, he says the doctors express the same concerns. “They realize that being on their own, although attractive in some ways, is now too risky and challenging. The experience of COVID-19 has changed their outlook.”

Experts recommend taking a hard business approach in these times, whether you plan to leave your practice through a sale, merger or retirement this year or in 10 years. “More than ever, practices should be looking at important financial keys that you can find in detailed reviews of all of your practice operations,” says Mr. Maller.

Mr. Pinto couldn’t agree more. “You’re the top administrator,” he points out. “You need to have a memorized command of important norms. Can you look through a CPT report and identify where you’re under- or over-utilizing services? Can you look at your YAG rates and know whether they’re within the norms and, if they’re below, understand why? What’s the normal percentage of cataract cases that involve a premium intraocular lens? Are you growing established patients by at least 5 percent per year?”

|

Your Tipping Point

Beyond practice valuation and developing a good exit plan, Dr. Piso, the psychologist and practice management expert who finds himself counseling more anxious doctors on how to navigate final career stages in the era of COVID-19, advises them to remember to look up from the balance sheet and CPT report so they can check up on themselves. He points out that diligence, planning and confidence are needed now more than ever to enable you to adopt the right mindset that will be critical for future success.

“Too often, ophthalmologists don’t pull the trigger to make these big life changes until they hit what we call their tipping point,” he says. “A tipping-point experience forces you to make changes and, as a result, makes you uncomfortable. It’s critical to keep in mind that people usually have to become uncomfortable before they’ll make positive changes. Rather than experiencing a negative tipping point experience that represents how you have been disempowered or makes you feel things are now out of your control, I urge doctors to be proactive. Create a tipping point of your own volition. This is what you want: To have a vision for going forward. Go for it.” REVIEW

1. American Academy of Ophthalmology membership data, accessed October 15, 2020. Data voluntarily provided by AAO members.