Buying a new piece of equipment for your practice can be exciting—but it can also be risky. With interest rates as high as they are, and reimbursements seemingly cut a few percentage points each year, in many cases the onus is on the practice to make sure a new device not only greatly enhances patient care but also doesn’t put too much of a financial strain on the business. Here, individuals from both the clinical and the practice management realms share their tips on making capital purchases. Also, ophthalmologists who responded to a technology survey weigh in on the factors that influence their purchasing decisions.

Evaluating the Potential Purchase

Balancing the benefits to patients and staff with the potential financial impact is one of the keys to bringing in new device.

Richard Jahnle, chief financial officer of Jahnle Eye Associates, which has two offices in suburban Philadelphia, says his practice looks at several factors when deciding on a large tech investment. “The first consideration might be if a device will make the office flow more efficiently, allow us to see more patients or automate things more effectively,” he says. “Another category is it could be a machine that increases our profitability, so if we invest in it, we know we’ll make enough to cover the cost of the machine and make a good return on our investment. The other category is a machine that can help the doctor get better outcomes depending on what exam or procedure he’s doing. In some cases, a machine will cover two or three of those factors. You want at least one of those requirements to be met to even consider purchasing it.”

|

| When evaluating new diagnostic technology, Peoria, Illinois, retina specialist Kamal Kishore says it’s imperative that his staff, who will be using the new device the most, have significant input into the purchasing decision. (Courtesy Kamal Kishore, MD). |

Kamal Kishore, MD, a retina specialist from Peoria, Illinois, who conducted a course at the most recent American Academy of Ophthalmology meeting on how practices can run more efficiently and effectively, says pursuing the standard of care often wins out if you’re mulling a purchase. “There are two ways you can make sure you need a piece of equipment,” he says. “The first situation is when a new technology comes out and you simply need it. For instance, when OCT came on the scene, it was apparent that retina treatment was going to be OCT-guided from then on. It was going to become the standard of care. The second instance is when your existing technology either breaks down or needs updating.”

Drilling down to a specific metric, Mr. Jahnle prefers return on investment. “As an example, we bought two digital ultra-widefield retinal imagers—one for each of our offices—to offer patients an alternative to being dilated,” he explains. “The charge for the patient who chooses to use it is $40. One of the devices cost $80,000, and the other $90,000. So, we quickly ran formulas to say, first, what percentage of our patients undergo an exam where we could potentially offer this to them. Second, of those, what percentage do we think will choose this digital imaging over a dilating drop and fundus exam, and how many can we do in a year.”

The other potential benefit of a new piece of technology isn’t just how much you’re reimbursed each time you use it, but the “opportunity revenue” of how much time it might free up to allow you to earn reimbursement dollars from other things, like seeing some more patients. Mr. Jahnle refers to this when he discusses the potential benefit of non-mydriatic, digital fundus imaging. “It had the advantage of leading to a faster exam compared to having to put in dilating drops and then waiting 15 minutes before the doctor could do the exam,” he says. “So, you can see more patients. This was kind of an added benefit.”

Dr. Kishore says that, once you acknowledge you need a new technology, then comes the question of which one to get? “This can be challenging because there are so many vendors,” he says. “For example, when it comes to OCT, there are many companies. Usually, we ask our friends what they have, take a look at the reviews, and then have a rep come in to do a demo. You can then talk about the price and so forth.

“For instance, we needed a fundus camera, and said that we need something like an ultra-widefield digital system,” Dr. Kishore continues. “We had an ultra-widefield company, the market leader, come in with a demo, followed by a demo of a competitor system. I asked each of my staff members who take the images which they preferred after the demos, and everyone favored the latter. I said, ‘Well, if you guys like that one, that’s the way it’s going to be,’ and we haven’t regretted it. The staff liked the ease of use, how easily it interfaced with our EHR and the fact that it had a reviewing station so you could view the images without being at the actual device.”

Dr. Kishore says it’s crucial to let the people who are going to be using the technology the most have a big say in the decision and that, sometimes, the device with all the latest bells and whistles isn’t always the one you wind up liking the most when you actually use it. “When we were looking into getting a new OCT system, we had the field narrowed down to three,” he recalls. “We had each company come in for demos, and we all favored the Topcon Triton. Even though the Triton doesn’t have OCTA [in the United States], it’s swept-source, so it’s much faster, and it takes a fundus photo at the same time as the OCT. Also, it will scan the nerve for glaucoma when you’re doing a macular scan. So, you get all three functions in one exam. It also doesn’t require dilation. It’s user friendly, and the staff liked it.” However, Dr. Kishore says if the device is for treatment—which he alone delivers—then he’ll be making the decision.

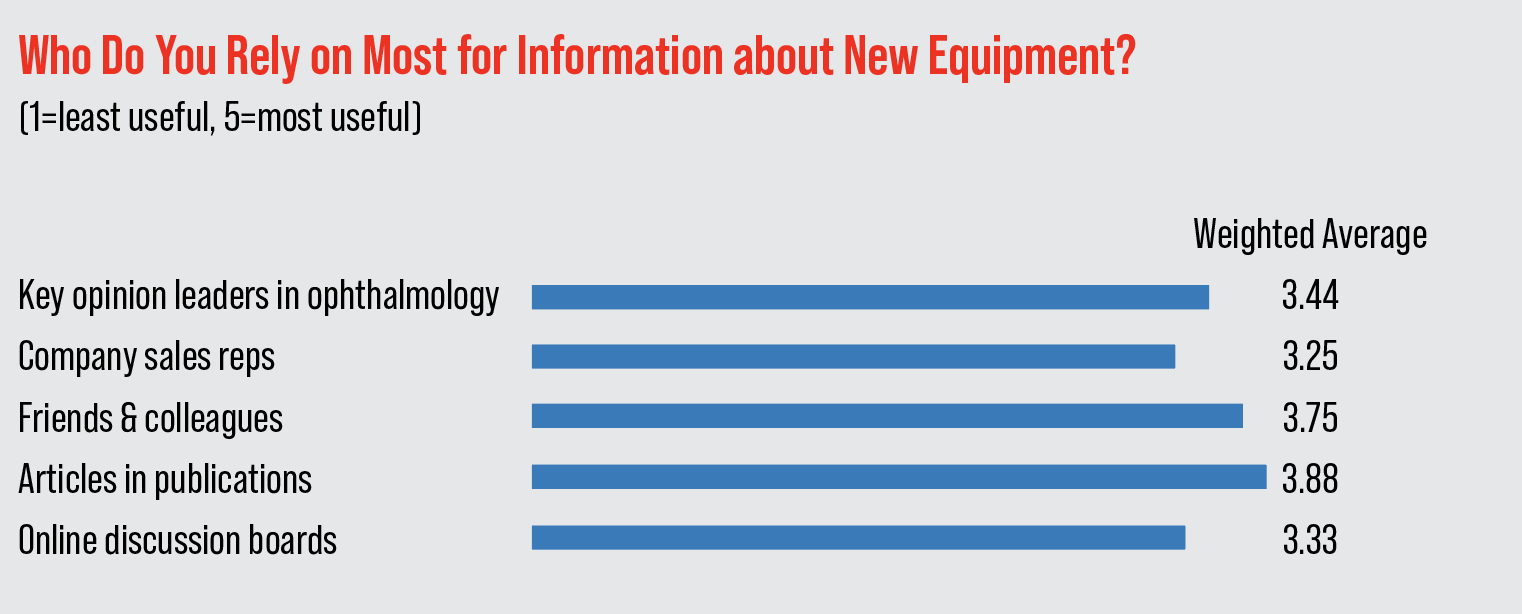

In a focus-group survey of our readers, 17 ophthalmologists weighed in on the equipment-buying process. They were asked to rate the importance of various sources of information from 1 (least important) to 5 (most). On average, the most important source for them is “articles in publications” (average score: 3.88), followed by “friends and colleagues” (3.75). (The rest of the scores appear in the graph below.)

|

New vs. Refurbished

Though you can sometimes save thousands by buying a refurbished machine compared to a new one, practices have to keep a couple caveats in mind.

“If you’re considering a refurbished device, the most important thing is the brand,” says Mr. Jahnle. “If you’re buying an imitation-type device from another country, there might be a risk even though the device might be a lot cheaper. We have a contact who works with some of the larger brands so, if, say, our OCT broke and we were looking for one, we could ask him if he knows of a practice that’s closed; maybe it’s sold the patient base but not the equipment yet. They may have gone to our contact and sold a five-year-old Zeiss OCT that we could take a look at.

“Of course, you have to be wary when buying refurbished, because you don’t know what happened to that machine, whereas a new one will have some form of warranty and support. For instance, the contact that we buy most of our new machines from has associates that are relatively local. So, if something goes wrong, we can text him and they’ll come over to make sure it’s working properly.”

Like buying an UHDTV at Best Buy, when you buy new, there’s always the question of whether or not to get the optional service contract. “We usually don’t buy the service contract, because they’re expensive,” avers Mr. Jahnle. And, we’ve been lucky in that we haven’t had a ton of issues with our machines. However, both of the ultra-widefield fundus imagers that we purchased, and I mentioned earlier, have had issues. The device uses multiple lasers, and if a laser breaks—and you haven’t bought their extended warranty—the charge for the part is $15,000. A laser broke once on us, and we didn’t have the extended warranty. At that point, we decided to get the extended warranty for both devices, because we figured if the issue happened with one, it could happen with the other. Though the extended coverage plan is expensive—$300/month for one machine and $250/month for the other—we figured it was worth it. It’s like insurance for something: You weigh whether it’s worth it to buy it.”

|

Renting vs. Buying

Since economics plays a large role in the purchase of new equipment, the question of renting vs. buying often comes up. Which route might work for you often depends on your particular situation.

“We’ve done both,” says Dr. Kishore. “If the technology you’re looking at is one that’s changing rapidly, I’d rather rent. That’s what we did with our previous OCT machine before the Topcon. For a technology that’s almost fully mature, like a retinal laser, then I’d rather buy it. It also depends on how much money you have and if there’s a 179 deduction the year you’re looking to buy in.”

For those unaware of the IRS 179 deduction, it’s a deduction the IRS occasionally implements that allows businesses to deduct the entire value of a large purchase in a single year (Dr. Kishore says the last time it was available, the limit for the deduction was $250,000), reducing their tax liability by a large amount, rather than having to splash out the cash all at once and then depreciate the item over several years.

“If there’s no 179 that year, and/or the money for the device may not be readily available, it makes more sense to lease the equipment,” Dr. Kishore says. “Also, often these lease programs give you the option to buy the device at its residual value after a certain time. Of course, you’re paying some money to the leasing company, but that’s OK because the lease expense is considered deductible right away as a leasing expense.”

Mr. Jahnle adds that the scale of the practice can impact the rent/buy decision. “If you’re a smaller practice, such as a solo ophthalmologist, and you only do 90 laser procedures a year, for example, maybe just have a service bring in a laser every six weeks for you to use for a day,” he says. “You can schedule a laser day where you’ll do 11 laser procedures.”

Review’s Readers Weigh in

In the focus-group survey on technology purchases, respondents shared their views on buying new equipment.

Two-thirds say they’ve bought equipment in the past two years. In that time, they say they acquired:

- an Argos biometer;

- RxSight Light-adjustable Lens;

- Widefield photography and OCT;

- Sofwave (for reducing brow and submental wrinkles and performing neck lifting), Acufit body contouring equipment, TriLift (muscle stimulator to combat skin wrinkles) and the OptiLight Intense Pulsed Light device;

- Diagnostic devices and artificial intelligence software;

- iTrace; and

- a surgical microscope.

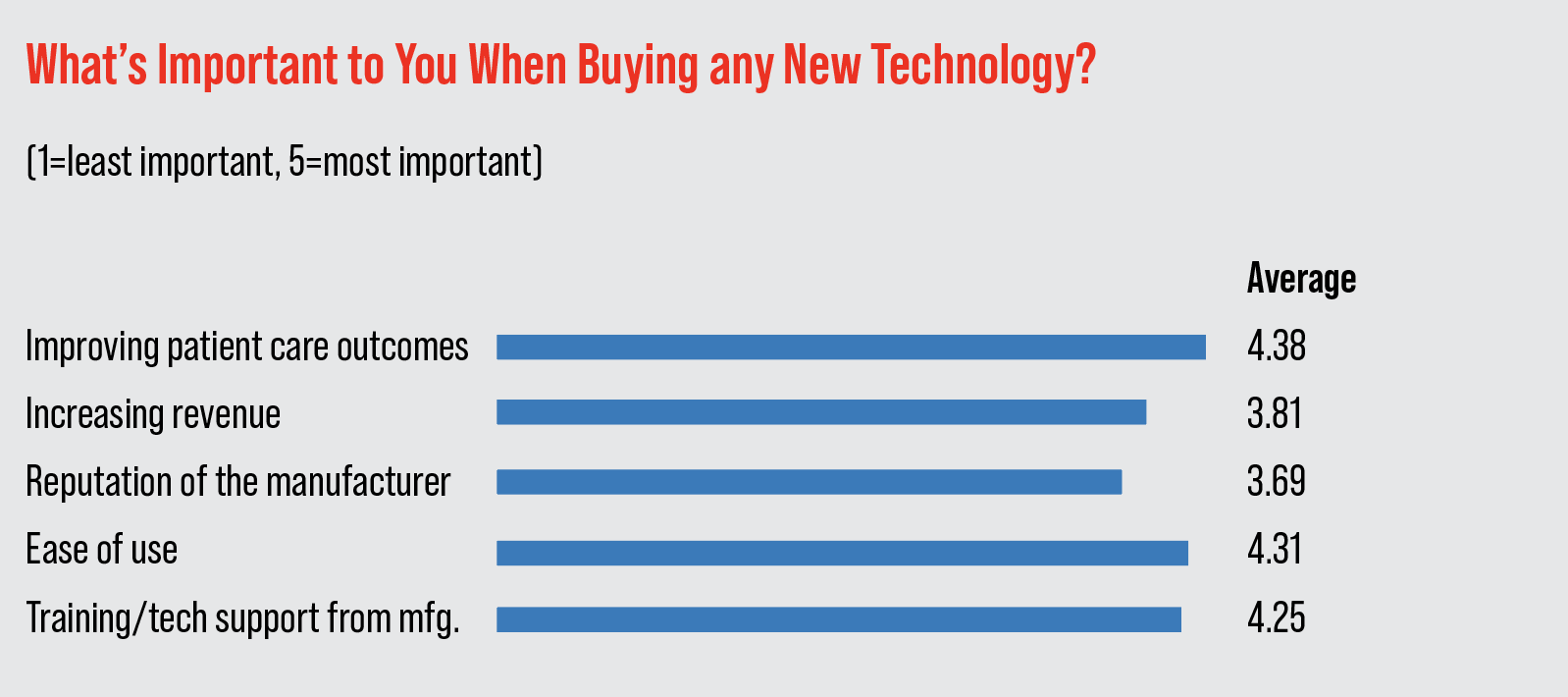

When asked to rate the importance of various factors when buying equipment on a scale from 1 (least important) to 5 (most), they rated “improving patient care outcomes” the highest, with an average score of 4.38. “Ease of use” came next (4.31), followed by “training/tech support from manufacturer” (4.25). (The rest of the factors and their average ratings appear in the graph above.)

The physicians also had thoughts on the whole experience of acquiring new technology, both the highs and the lows.

One surgeon from Louisiana doesn’t like “the lack of transparency in pricing,” when evaluating new equipment. A surgeon from Texas thinks similarly, saying the part he likes least is “negotiating the price.”

A surgeon from California says it’s not so much the price of new technology that makes the buying process difficult, it’s the dwindling resources afforded ophthalmology by payors. “Investing in new technology—even replacing old equipment—becomes ever challenging as reimbursement rates continue to decline,” he says. “We need insurance/Medicare payment reform that at least keeps pace with inflation.”

New York surgeon Jimmy Hu says that, despite impediments like cost and decreased reimbursement, physicians ultimately find a way to keep pace with technology. “Our clinics are demanding increased patient volumes and throughput,” he says. “Our tools must be dependable, easy-to-use and produce useful measurements and outcomes.”

Mr. Jahnle and Dr. Kishore have no financial interest in any of the products mentioned.