It’s not uncommon for ophthalmologists today to be concerned about the future of the profession. Faced with everything from potentially huge cuts in reimbursement to mountains of paperwork and payer scrutiny, it makes sense to worry that the best and brightest students might avoid medicine and/or ophthalmology and choose less worrisome careers. That doesn’t appear to be the case.

Here, a number of individuals who are part of the process of bringing new ophthalmologists into the field share their thoughts on how students, residents and young doctors are reacting to these concerns; how these individuals differ from previous generations; and how the future of ophthalmology may be shaped by this new wave of aspiring doctors.

The Best and the Brightest?

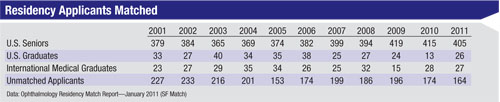

One way to judge the caliber of ophthalmology’s applicant pool is to look at the number of applicants and their credentials compared to previous generations.

“Ophthalmology is not in trouble from the standpoint of attracting the best and the brightest,” says Susan H. Day, MD, chair of the department of ophthalmology at California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco, and past board director of the American Board of Ophthalmology and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. (Dr. Day has been a program director since 1997.) “The number of applicants to ophthalmology seemed to reach a low point in the mid-1990s, but it’s been slowly rising since then. Our program has three slots per year in the match, and we receive 350 to 400 applications every year. We interview 50 to 60 individuals from this pool.

|

Jake Waxman, MD, PhD, vice chair for graduate medical education at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, reviews all of the applications to the residency program and interviews the applicants; he’s been doing this for 14 years. “The number of applicants to our program has not been decreasing,” he says. “Each year we receive between 500 and 600 applications to fill six residency positions, and every year the applicants’ credentials get more impressive. These folks have CVs that rival those of some of our faculty. They have first-author papers, volunteer experience and huge service commitments. The average USMLE score for ophthalmology applicants is now in the 99th percentile. They all have research experience and play the piano and run track. I’m not sure I’d get into a program anywhere if I had to compete against these kids.”

|

Drs. Waxman and Day point out additional noteworthy characteristics of the current applicants:

• Variety of educational background. “It used to be that almost everyone heading into medical school had a science degree,” says Dr. Waxman. “Today you’re as likely to see an applicant with a drama or literature degree as you are to see someone with a physics degree. As a result, our students come to us with a very different perspective on life.”

Does the lack of a science degree put residents at a disadvantage? “Sometimes when we’re doing optics homework and there are math problems to solve, it can get in the way,” Dr. Waxman acknowledges. “But most of the time, the answer is no. You end up with doctors who are very human—real people with interests outside of medicine. They don’t identify themselves as being doctors and nothing else. They don’t live, breathe and eat the profession, the way many people did in the past. Sometimes I wonder whether that’s a disadvantage, but other times it seems to me that these folks are more likely to have a balanced approach to life and work than some of us who’ve been doing it the other way for a while.”

• More years of training. “Many ophthalmology applicants now come in with more than the traditional four years of medical school,” observes Dr. Day. “Some have had previous careers; others have prolonged their time in medical school. Many medical schools now offer options such as a master of public health, or an MBA or PhD in basic clinical research as part of the medical school program. Students take advantage of these options at least in part because there’s a perception that ophthalmology is very competitive. Whatever the motivation, we’re seeing many ophthalmology resident applicants with multiple graduate degrees.”

• Public service experience. “The average ophthalmology applicant has always been pretty strong academically,” notes Dr. Waxman. “What we’re seeing more of today is the more well-rounded individual who, for one thing, has definitely demonstrated an interest in public service. A lot more of our ophthalmology applicants have done volunteer work in ophthalmology or other fields of medicine, or literacy programs. It’s a very rare application we see today in which the applicant hasn’t demonstrated a commitment to serving the community, and that’s heartening.”

New Generation, New Profile

The American Academy of Ophthalmology’s membership division does a survey of its membership every two years. “We send out about 14,000 surveys to U.S. and international members,” says Tamara R. Fountain, MD, head of the AAO’s member services division. “That includes both U.S. and international members in training, or MITs, defined as residents and fellows still in their training period. This is a fairly representative sample, as about 82 percent of all ophthalmology residents join the academy in their first year of residency. Among the practicing doctors in the U.S. and international member categories, we also look specifically at young ophthalmologists in their first five years of practice, whom we refer to as YOs. Then, we compare the responses from MITs and YOs to those from the membership at large.

“This year our survey response rate ranged from 14 to 20 percent among the groups,” she notes. “More than 2,000 surveys were returned—960 from U.S. members, 676 from international members, 289 from U.S. members in training, and 199 from international members in training.”

Dr. Fountain shares a few highlights from the data:

• Gender balance. “Our younger members are increasingly likely to be female, and less likely to be Caucasian,” Dr. Fountain says. “Our general membership is currently about 25 percent female and 75 percent male. In contrast, our fellows and residents are 38 percent female, and our young ophthalmologists are 42 percent female. As many doctors are aware, the proportion of women in medical school classes is approaching 50 percent, so we’re likely to see more women going into the profession as time goes by.”

• Ethnicity. “Three-quarters of our overall current membership is Caucasian, and 12 percent of our members are Asian, a group that includes the Pacific Rim as well as India,” says Dr. Fountain. “But our YOs and MITs are about 30 percent Asian and 57 percent Caucasian.”

Dr. Day has also noted the shift. “In years past, most applicants would have last names like Jones or Smith. Today, there’s a tremendous diversity in our applicant pool from the perspective of both ethnicity and gender.”

• Increased fellowship training. “The current residents are less likely to go into solo practice,” notes Dr. Fountain. “Only one in 10 expects to be purely a general ophthalmologist. For comparison, about 40 percent of our established U.S. members identify themselves as general ophthalmologists. About two-thirds of the residents are planning to do fellowships; retina/vitreous and cornea/external disease are the top two choices, with glaucoma in third place.

“In our surveys, those who plan to complete a fellowship indicate that they believe this is critical in order to reach the position they’d like to attain and be successful financially,” she continues. “I think they have the impression that subspecialists are able to command higher salaries and that subspecializing, in general, is a more desirable situation. This trend could reflect lifestyle considerations as well—although our survey data confirm that subspecialists work, on average, seven to eight hours more per week than general ophthalmologists. I’m not sure the younger people are aware of that. Subspecialists see about the same number of patients and spend about as much time in clinic, but they spend more time in surgery.

“The trend toward more fellowships might also be a reflection of the general trend in medicine of fewer medical students wanting to go into primary care and family practice,” she adds.

Dr. Day notes that although there’s a clear trend toward more residents doing fellowship training, that doesn’t mean that a given resident will end up limiting his or her practice to that subspecialty area. “Many people do a fellowship year in order to gain additional expertise in one area, but then go on to do comprehensive ophthalmology,” she points out. “Some people have speculated that one reason residents are inclined to do fellowships is that they’re still a little insecure about going into practice immediately after the completion of residency. A fellowship is one way to gain more experience before going into practice.”

Dr. Fountain adds that having subspecialty skills could actually work to a young ophthalmologist’s advantage. “Some group practices will be looking for subspecialists to round out their stable of talent,” she says. “Older ophthalmologists are more likely to be generalists, so when recruiting they may want to get subspecialists so they don’t have to refer patients out; they can keep that revenue in the practice.”

|

Today’s residents and beginning ophthalmologists don’t always share the same perspectives as older practicing ophthalmologists:

• A different perspective on being a doctor. One of the things that’s changed in recent decades is the image of doctors as infallible, heroic figures. Today, most Americans realize that doctors can’t possibly know everything and are as capable of a mistake as anyone else. That doesn’t seem to have had any negative impact on young people’s desire to go into medicine, however. “The average medical students and ophthalmology residents don’t want to be god,” observes Dr. Waxman. “They like the idea that they’re human just like the patient, and that’s the way they’re going to interact with the patient. It used to be that you’d see a patient, diagnose him, tell him what he had and tell him what to do, and you could pretty much expect that he’d do it. Now, you have to explain to the patient what it’s all about. I think that’s probably a good thing, and I think the newer generation sees it that way.”

• High levels of satisfaction (so far). “Ninety-one percent of our young ophthalmologists are satisfied with their choice of career, and 71 percent would recommend ophthalmology to others,” notes Dr. Fountain. “However, only 64 percent are satisfied with their practice situation. That number may reflect the fact that these young doctors are just out of training in their first jobs. Unlike the generations ahead of them, where a lot of people went into solo practice and stayed in solo practice, more YOs are joining group practices. If they feel that things aren’t working out for them, they’re voting with their feet.

“Among the members still in training, 88 percent are extremely satisfied with their career choice so far, and 80 percent would recommend ophthalmology as a career choice,” she continues. “That’s compared to 67 percent of the U.S. membership at large, so those in training tend to be more enthusiastic about their career choice. Also, 75 percent of the MITs rate their current residency training program very highly, and 85 percent are very or extremely satisfied with the AAO.” Dr. Fountain notes that the younger ophthalmologists also express satisfaction with the academy; 80 percent are satisfied overall, and two-thirds are very or extremely satisfied with the academy’s goals of meeting their particular needs.

• Social consciousness. Dr. Day says that although her opinion is heavily influenced by the people in her program, she does believe that current students generally feel a sense of responsibility to society. “They’re concerned about global issues, as well as health care delivery disparities,” she says. “This is easily observable in residency programs because so much of residency training is done at safety-net hospitals, where people don’t have a lot of choice about where they get their medical care. The residents see social need every day.”

Dr. Waxman agrees, noting that current residents seem to be going into the profession for all of the best reasons. “They want to help people and take care of people,” he says. “They’re not focused on ophthalmology as a respected profession that’s remunerated well. There’s a strong sense of calling to medicine in general and ophthalmology in particular as service to the community.”

• A different work ethic. “When I became an ophthalmologist, we all worked Saturdays,” says Robert Osher, MD, professor of ophthalmology at the University of Cincinnati and in private practice at the Cincinnati Eye Institute. “That was a given. And during the week we worked late until the last patient was seen. The attitude now is, ‘I’m entitled to time off; when I’m not on call, I don’t want to be bothered.’ To this day, I still give every patient my home phone number. The upcoming generation wouldn’t consider that; when they’re done with work, it’s their time to do with as they please.”

“Young physicians seem to value work-life balance more than older generations,” agrees Dr. Fountain. “In any case, outside of the clinical day, there’s definitely a lot more competition for the time and educational interests of our younger members. One reflection of that is that we’re seeing a decrease in young members in the state and local medical/ophthalmological societies, across the board. All of these organizations are scrambling to appeal to a younger membership. The younger doctors are less likely to set up a solo practice, and they’re more likely to join a large group or pursue a university position than the current established membership. I think that might be a nod to lifestyle. It might also reflect the increasing numbers of women entering the field who want some flexibility in their work life.”

“It’s easy to take a dim view of [the new work ethic],” says Dr. Waxman. “It’s easy to say, ‘This is all the fault of the ACGME duty-hour rules.’ On the other hand, medicine really isn’t supposed to be a solo sport any more. A lot more of what you do in training these days is about learning how to get along in the system; how to work with other members of the health-care team to best take care of the patient.”

Dr. Waxman does see potential good in this shift. “Maybe this attitude will result in lower alcoholism, substance-abuse and divorce rates than we find in the folks who’ve been working 80 or 100 hours a week from the very beginning,” he says. “Maybe this way is the right way—a better life-work balance.”

Dr. Osher agrees. “In the final analysis,” he says, “this is probably a good thing.”

|

One obvious difference from previous generations of ophthalmologists is that the newcomers have grown up using the Internet and digital media, with both positive and (potential) negative consequences.

• Different information sources. “Our young members are more likely to turn to the Internet for their CME content rather than a journal, CD-ROM or DVD,” notes Dr. Fountain.

Dr. Osher has observed this as well. “Our residents are far more capable than previous generations when it comes to handling the information glut that doctors currently have to manage,” he says. “They’re not at all intimidated by computers.”

“Today’s residents are very facile at obtaining and retrieving information electronically,” agrees Dr. Day. “Their ability to review the medical literature, as evidenced in their grand rounds presentations, is exemplary. But there are limits to how much one can rely on that. Residency education remains a highly experiential learning process, where one must still take care of the patient and operate on the eye. Self-reflection and assessment over the triumphs and failures of various

treatments, coupled with invaluable faculty mentoring, are equally essential components of our educational system. They can’t be duplicated by anything you hold in the palm of your hand.”

• Hand-eye coordination. “Current students’ hand-eye coordination is far superior to what most of us had when I went through residency,” says Dr. Osher. “They’re used to doing fine movements with their fingers. They’ll make spectacular surgeons.”

• Less facile one-on-one with patients? Dr. Osher says he’s observed that some of the residents are not as accustomed to communicating face-to-face. “The new generation is used to communicating electronically,” he points out. “After surgery, I’m very comfortable putting my arm on the patient’s shoulder and saying ‘You did great.’ They’re not as comfortable looking you in the eye and touching you.”

But Dr. Waxman notes that better hand-eye coordination and communication difficulty may not be an accurate description of every new doctor. “It’s certainly true that a good number of the residents I work with are naturally talented in surgery in a way that I don’t remember being when I was in training,” he says. “But occasionally we have residents who need a little more training than that.

“I also see a variety in terms of social skills,” he continues. “Remember, we’re recruiting fewer organic chemistry majors and more English literature majors today; that means doctors with a broader range of interest, which often translates to having good social skills.”

Dr. Day says she hasn’t observed a communication problem in residents, but agrees that it’s an issue teachers need to be aware of. “Educators divide essential traits of physicians into six categories, one of which is communication skills,” she points out. “We’re required to assess communication skills, along with the other five competencies, for each and every resident at least twice a year. And, we’re required to provide feedback, both in a summary fashion and a ‘this is what we need to work on moving forward’ fashion. I’m very optimistic that with good teachers and the right learning environment, communication skills—which the public very much wants in doctors—will continue to be strengthened as part of the educational process.”

Dealing with the Downsides

What about all the things that are currently frustrating ophthalmologists who have practiced for years?

“Of course, there are things in our field that are not ideal,” says Dr. Osher. “We have terrible regulatory hurdles, a lack of funding for R&D, reimbursement problems, CME guidelines that make no sense and other issues. I know that many established surgeons are concerned that these kinds of problems will scare newcomers away from ophthalmology, but in my experience that’s not true. The incoming students aren’t concerned with the same issues that you and I are worried about. My son graduates from his residency this year and is applying for a retinal fellowship; he couldn’t care less about diminishing reimbursements.

“It’s a matter of perspective,” he continues. “If you go from 10 to eight, you see it as a loss. If you’re going from one to eight, it’s a pretty big gain. Furthermore, when people are doing something satisfying that they enjoy and they’re giving back to society, they don’t worry too much about what they’re making because every day is enjoyable. I believe medicine will always have that attraction, and ophthalmology represents the best of medicine.”

|

“In any case, the fact that we’re still seeing people flocking to medical schools and becoming doctors is a testament to the fact that people want to go into it for the right reasons,” she adds. “Our surveys suggest that our MITs and YOs are very happy with their career choice, excited about the field and likely to recommend it. It could very well be that they haven’t hit the realities of being in practice yet. But the fact that they are so indebted and still so hopeful does bode well.”

Dr. Waxman says he’s seen an increase in applicants’ awareness of these issues, but a surprising lack of cynicism about them. “Instead, their reaction seems to be one of wanting to be part of the solution,” he says. “Rather than becoming discouraged, these people have committed more and more of their time to public service.” He adds that most of the students and residents he deals with are incredibly enthusiastic. “They’re idealists,” he says. “For them, the fact that they may only make $150,000 starting salary means at least they won’t be in med school anymore, hemorrhaging $45,000 a year.”

Dr. Day says the residents are aware of ophthalmology’s problems, but their reactions depend on the personality of the individual. “In any case, I don’t think many faculty would look students in the eye and say, ‘Don’t go into ophthalmology,’ ” she points out. “As a teacher, my message is: If you focus on the patient, these other issues, though they will be there, will somehow be faced and dealt with favorably.”

Outlook for the Future

“Right now, medicine is very sought-after as a career,” says Dr. Osher. “Our enrollment is up and our applications are up. One reason for this is that medicine is a sure way of making a living in uncertain times. Another factor is that television shows make medicine seem romantic, exciting, dramatic and glamorous. More importantly, people realize that there’s nothing more enjoyable than working with other human beings—not to mention being compensated for work you find very interesting. I think there will always be tremendous demand for a career in medicine.”

Dr. Osher adds that he’s noted it’s fairly common for children to follow their parents into ophthalmology. “I think that’s because the parents usually tell the kids they have a great life,” he says. “That doesn’t necessarily mean great reimbursement, but you don’t see any ophthalmologists out walking the streets unemployed. And if you’re going to make a living, you might as well pick a career that’s very satisfying. That’s what ophthalmology offers.”

One potential cause for concern is that fewer medical schools are requiring ophthalmology as a core elective. “That means that fewer students are likely to choose ophthalmology, unless they already have an interest in doing so,” notes Dr. Fountain. “Fewer medical students are being exposed to ophthalmology in the course of their medical training, and some doctors end up not even knowing the basics of an eye exam. I’m sure this is the result of economics and time constraints, but it’s a potential concern for our field.”

Nevertheless, Dr. Fountain says she’s hopeful and optimistic about the future. “The younger doctors who will take over the reins going forward are informed, educated, socially conscious, passionate and overwhelmingly enthusiastic about both their career choice and the academy, as our surveys show,” she says. “I think that’s a good sign—for both the profession and the public.”

Dr. Day agrees. “Judging by the quality of people in our residency program, these are mature, thoughtful, well-meaning individuals who see ophthalmology as a means to make the world a better place.”

“I think the quality and motivation of current applicants bodes nothing but well for ophthalmology,” adds Dr. Waxman. “You can grouse about the field all you want in terms of decreasing remuneration, autonomy and so forth. But from the point of view of the profession going downhill because we’re getting less qualified, less extraordinary new doctors—not a chance.”