COVID-19 is an unprecedented challenge that’s brought providers in internal medicine, emergency medicine, anesthesia and critical care to the forefront. Specialists, amidst changes that include cancellations of clinic and procedures and adoption of telemedicine, are placed in the special position of weighing the tenets of public health against the needs of their unique patient populations. A field that epitomizes this is ophthalmology and, perhaps even more so, oculoplastics and orbital surgery. In this tumultuous time, we need to think critically about ensuring the best possible outcomes for our patients and for our practices, with a forward-focused approach. Here, we’ll cover some areas of oculoplastics that have been affected by the pandemic, and how these areas can recover now that practices are beginning to reopen.

Minimizing Spread

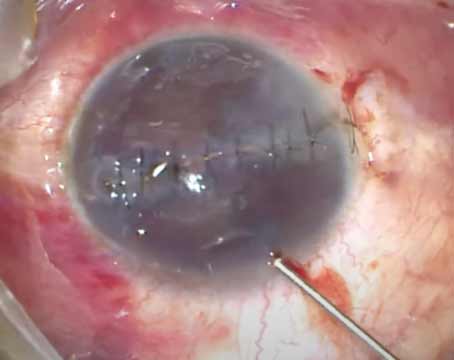

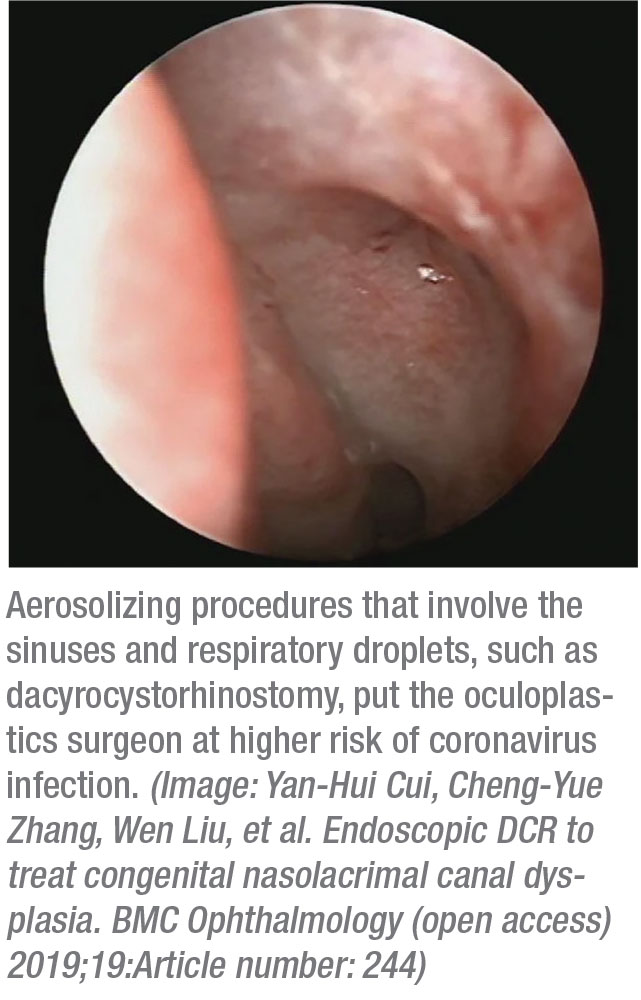

As has been pointed out in the early days of the pandemic, ophthalmologists are at high risk of exposure to higher viral loads due to their proximity to the patient’s face and contact with conjunctiva and tears, which can be sources of viral transmission.1 Because of these risks, we’ve been compelled to minimize office staff to maximize patient safety, and many practices ensure that older physicians have a higher threshold for in-person interactions due to higher risk of COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality in older populations.2 Aerosolizing procedures involving the sinuses and respiratory droplets, such as dacryocystorhinostomy, orbital fracture repair and orbital decompressions, as well as any operations that require general anesthesia and intubation, place oculoplastic surgeons at particularly high risk.3 As part of the public health campaign against COVID-19, initial recommendations were to suspend elective procedures, identify high-risk patients and undertake urgent cases with heightened protections. Though some elective procedures are starting to be performed again, the latter two recommendations remain as important as ever.4

Specific Procedures

Our prime directive is to “first do no harm,” but this becomes a challenging conundrum as we carefully reopen our country.

For example, many cancers of the head and neck extending to the orbit double in size within a few months.5 Numerous studies have linked the extent of orbital involvement or metastasis of cancers directly to survival rates and other outcomes, necessitating prompt and urgent treatment.6,7 As such, all orbital/periorbital lesions that are concerning for metastatic or aggressive malignancies, such as sebaceous cell carcinoma or melanoma, should be worked up and managed in a timely fashion.

A similarly thoughtful approach should follow for traumatic reconstructions. A large meta-analysis has recommended immediate reconstruction for specific findings, including diplopia and entrapped muscle tissue associated with oculocardiac reflex, significant globe displacement threatening vision and marked extraocular motility restrictions.8 In the COVID-19 era, you can consider delaying surgeries for those without proven entrapment, leaving repair of enophthalmos or hypoglobus for a later date, but this should be weighed against the technical challenges presented by delayed orbital scarring. It thus becomes difficult to propose clear guidelines in our field, and all orbital surgery cases must be considered individually in terms of their potential risks and benefits.

Telemedicine

Despite these significant challenges, our patients remain our priority. Fear, anxiety and anger are now well-documented among patients and providers during the COVID-19 pandemic.9 Patients may no longer be making office visits out of fear for their own safety, while providers may close practices for similar reasons. To reopen and maintain our practices, we need to send a message to our patients that every precaution is being taken in our decision to work, and that we’re still available to them. To achieve this, we’ll need to incorporate telemedicine wherever possible. This may be the only way to prioritize our public health while ensuring patients unwilling to come into the office are provided the best possible care under the circumstances.

|

Telemedicine has been shown to work particularly well in ophthalmology in general and oculoplastics in particular. Data from an ocular teleconsultation program has suggested that oculoplastic consultations made up nearly two-thirds of teleconsultations that included photographs.10 In other contexts, oculoplastics clinics successfully employed telemedicine for initial aesthetic consultations and follow-up appointments for myogenic ptosis, which improved patient flow and revenue.11,12

Telemedicine transfer of live images and videoconferencing have also been broadly studied for diagnostic accuracy. In a systematic quality assessment, telemedicine was found to be comparable to in-person visits in various subspecialties of ophthalmology, including oculoplastics.13 The dermatology literature similarly supports the use of telemedicine for inpatient consult triaging and consultations of skin lesions suspected to be malignant.14,15 Taken together, there is a broad role for telemedicine across many types of visits in oculoplastics. It would be reasonable to extend the use of telemedicine to triage other conditions such as eyelid lesions and proptosis. We could institute a two-tiered approach to triage via telemedicine and offer in-person visits only for those patients who need it.

Looking beyond this pandemic, telemedicine may provide long-term benefits for our practices. In addition to improving triage and flow, as well as generating revenue, telemedicine can also improve patient access, particularly in rural areas where there are deficits of subspecialists.16,17 Physicians may be wary of telemedicine, cautious of the potential liability that could stem from diagnosing conditions without an in-person physical exam.18 There are data to suggest that telemedicine may not increase rates of malpractice claims due to its low-risk nature, but these studies don’t address complex diagnoses such as trauma or orbital tumors.19 Many payers already cover some types of telemedicine, but important challenges remain, such as reimbursements rates and coverage across state lines. New legislature will need to evolve to address these issues of liability and coverage before telemedicine can truly become mainstream. State laws that limit prescriptions for telemedicine providers would also need to be updated accordingly.

In the short-term, some of these restrictions were addressed by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. These changes allow providers to prescribe controlled drugs by telemedicine in accordance with federal and state government policies, waive requirements of pre-established relationships for Medicare coverage, allow certain health plans to cover telemedicine without a deductible, enhance reimbursements for telemedicine services and fund programs to increase telemedicine access in rural health clinics and non-profit hospitals.20 These efforts are designed to temporarily mitigate both the liability and cost of telehealth for providers. Oculoplastic providers in rural areas and not-for-profit hospitals should take advantage of these changes to establish telemedicine components in their practices. If applied thoughtfully, these changes may serve as a catalyst to promote adoption of telemedicine more broadly.

Financial Aid Review

The financial implications of COVID-19 are far-reaching, and force us to reexamine many aspects of how we practice, including the financial end of things. Here’s a review of some of the recent financial lifelines some practices were able to make use of.

The CARES Acts, through the Small Business Administration, have allowed private practitioners to apply for loans through the Paycheck Protection Program. This provided oculoplastic practices with fewer than 500 employees, sole proprietors, and individuals loans of up to 250 percent of an average monthly payroll cost for eight weeks, up to $10 million, at a maximum interest of 4 percent. Borrowers were further eligible for loan forgiveness if the funds were used for eligible expenses (payroll costs, mortgage or utility costs) within the first eight weeks, with a reduction if there are layoffs or wage reductions to employees.

For practices with more immediate needs, such as sick leave for employees, rent or mortgage payments, an alternative loan program was the Economic Injury Disaster loan, which provided an up-front advance of $10,000 within three days and loans at a rate of 3.75 percent for small businesses and 2.75 percent for private nonprofits.21 The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services also administered a Provider Relief Fund program to provide grants to practices or individuals with increased costs or lost revenue from COVID-19.

Finally, there is an employee retention tax credit, equal to 50 percent of qualifying wages that an employer pays their employee in a calendar quarter.22 Together, these changes helped make it easier for providers to minimize in-office staff while retaining them on the payroll.

Technology Solutions

Our response to this crisis today can dramatically impact our specialty in the long term. We may see multiple waves of this disease, and the changes we implement today may need to remain in place for years. COVID-19 may provide the necessary push for doctors and payers to embrace the options that information technology can offer.23 In addition to using telemedicine, we imagine a future in which doctors can take advantage of machine learning and artificial intelligence, which have been particularly impressive in ophthalmology for diagnosing a variety of retinal conditions.24,25 In oculoplastic surgery, machine learning may use photographs to guide procedure selection and operative decision-making.26 It may help us discern more from histories and images, and rely less on limited virtual physical exams. Finally, the pandemic may force our nation to re-examine payment models, which currently place financial burdens on practices when procedures are postponed.

In conclusion, COVID-19 is unlike anything most of us will ever see in our lifetimes yet, despite its tragedy, it’s a unique opportunity for us to evolve. While many of these changes are temporary, they still represent efforts to maximize patient care while maintaining revenue and minimizing legal risk. Seeing these changes as an opportunity to make a long-standing impact in our specialty will ultimately benefit both patients and providers. This is the silver lining in these trying times, and we should seize the opportunities that it provides with an eye toward a better future. REVIEW

Dr. Kim is an ophthalmology resident at the University of Pennsylvania’s Scheie Eye Institute. Dr. Briceño is an oculoplastics specialist at Scheie and an assistant professor of clinical ophthalmology at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine.

1. Wu P, Duan F, Luo C, et al. Characteristics of ccular findings of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Ophthalmol 2020;31;138:5:575-578.

2. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:10229; 1054-1062.

3. Wax RS, Christian MD. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can J Anesth. 2020 ;67:5:568-576.

4. Recommendations for oculoplastic surgeons during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Society of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. https://www.esoprs.eu/news/recommendations-for-oculoplastic-surgeons-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/. Accessed 11 June 2020.

5. Jensen AR, Nellemann HM, Overgaard J. Tumor progression in waiting time for radiotherapy in head and neck cancer. Radiother Oncol 2007;84:1:5-10.

6. Shah JP, Kraus DH, Bilsky MH, Gutin PH, Harrison LH, Strong EW. Craniofacial resection for malignant tumors involving the anterior skull base. Arch Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg 1997;123:12:1312-1317.

7. Valenzuela AA, Archibald CW, Fleming B, et al. Orbital metastasis: Clinical features, management and outcome. Orbit 2009;28:2-3:153-159.

8. Dubois L, Steenen SA, Gooris PJJ, Mourits MP, Becking AG. Controversies in orbital reconstruction - II. Timing of post-traumatic orbital reconstruction: A systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015;44:4:433-440.

9. Park SC, Park YC. Mental health care measures in response to the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Korea. Psychiatry Investig 2020;17:2:85-86.

10. Mines MJ, Bower KS, Lappan CM, Mazzoli RA, Poropatich RK. The United States army ocular teleconsultation program 2004 through 2009. Am J Ophthalmol 2011;152:1:126-132.e2.

11. Gushchin AG, Crum AV, Limbu BB, Quigley EP, Seward MS, Tabin GC. Simbu Ptosis: An outreach approach to myogenic ptosis in eastern highlands of Papua New Guinea-Experience and results from a high-volume oculoplastic surgical camp. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2017;33:2:139-143.

12. Hwang CJ, Eftekhari K, Schwarcz RM, Massry GG. The aesthetic oculoplastic surgery video teleconference consult. Aesthetic Surg J 2019;39:7:714-718.

13. Tan IJ, Dobson LP, Bartnik S, Muir J, Turner AW. Real-time teleophthalmology versus face-to-face consultation: A systematic review. J Telemed Telecare 2017;23:7:629-638.

14. Chuchu N, Dinnes J, Takwoingi Y, et al. Teledermatology for diagnosing skin cancer in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;4;12:12:CD013193.

15. Barbieri JS, Nelson CA, James WD, et al. The reliability of teledermatology to triage inpatient dermatology consultations. JAMA Dermatology 2014;150:4:419-424.

16. Nelson R. Telemedicine and telehealth: The potential to improve rural access to care. Am J Nurs 2017;117:6:17-18.

17. Thompson MJ, Lynge DC, Larson EH, Tachawachira P, Hart LG. Characterizing the general surgery workforce in rural America. Arch Surg 2005;140:1:74-79.

18. Parimbelli E, Bottalico B, Losiouk E, et al. Trusting telemedicine: A discussion on risks, safety, legal implications and liability of involved stakeholders. Int J Med Inform 2018;112:90-98.

19. Fogel AL, Kvedar JC. Reported cases of medical malpractice in direct-to-consumer telemedicine. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc 2019;321:13:1309-1310.

20. S.3548 - 116th Congress (2019-2020): CARES Act; 2020. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/3548/text#toc-id1AEE82D6584D4472998847A5E8177FC9. Accessed 14 April 2020.

21. Administration USSB. Coronavirus Relief Options. https://www.sba.gov/funding-programs/loans/coronavirus-relief-options. Accessed 9 April 2020.

22. IRS. FAQs: Employee retention credit under the CARES Act | Internal Revenue Service. https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/faqs-employee-retention-credit-under-the-cares-act. Accessed 9 April 2020.

23. Simpkin AL, Dinardo PB, Pine E, Gaufberg E. Reconciling technology and humanistic care: Lessons from the next generation of physicians. Med Teach 2017;39:4:430-435.

24. Gulshan V, Peng L, Coram M, et al. Development and validation of a deep learning algorithm for detection of diabetic retinopathy in retinal fundus photographs. JAMA 2016;316:22:2402-2410.

25. Peter Campbell J, Ataer-Cansizoglu E, Bolon-Canedo V, et al. Expert diagnosis of plus disease in retinopathy of prematurity from computer-based image analysis. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016;134:6:651-657.

26. Kanevsky J, Corban J, Gaster R, Kanevsky A, Lin S, Gilardino M. Big data and machine learning in plastic surgery: A new frontier in surgical innovation. Plast Reconstr Surg 2016;137:5:890e-897e.