The COVID-19 pandemic catapulted telemedicine into the health-care vanguard when the “lockdown” and social distancing guidelines were in place, but now that the United States has transitioned to its new normal, does telemedicine still have a role in daily ophthalmic practice? We spoke with several subspecialists to find out how they’re using telemedicine now and which aspects they feel need improvement.

Telemedical Tales

“During the pandemic, medical specialties that relied more on history-taking or counseling and less on clinical examination or advanced imaging were more readily able to move to virtual visits and telemedicine,” explains Ian C. Han, MD, a retina specialist who practices at the University of Iowa Hospital and Clinics. “Much of ophthalmology practice was considered ‘elective’ for a time early in the pandemic, and visits considered routine were delayed rather than pursued as scheduled.

“Retina visits were much harder to delay, as we have a higher percentage of urgent/emergent conditions (e.g., retinal detachment), and higher risk of vision loss due to lapses in care (e.g., from pauses in intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy),” he continues. “As a result, our department didn’t pursue any robust mechanisms for virtual retina visits.” He says this held true even after many of the pandemic restrictions were lifted, and despite the fact that he practices in “a major academic center in the rural Midwest where patients often drive many hours for clinic visits.”

Retina specialist Sunir Garg, MD, of Wills Eye Hospital and Mid-Atlantic Retina in Philadelphia, agrees, that without the ability to examine the patient’s retina, they were fairly limited in what they could offer patients. “We’d get a lot of calls saying, ‘My eye is red after the injection,’ and we could tell if there was a subconjunctival hemorrhage, so that was potentially helpful for patients. But for most patients, when the call was about blurry central vision and trouble seeing, it was hard for us to know what was going on without looking at the retina.

“We did telemedicine for a little while, but eventually it was more trouble than it was worth,” he continues. “We haven’t gone back to it. There are some who set up a sort of OCT scanning center in an office with basically a technician and an OCT machine, where the doctor would read it remotely, but we didn’t do that.”

At one point during the pandemic, Dr. Garg’s practice tried remote scribing to reduce the number of people in the clinic. “Traditionally, a person with us in the exam room will help enter the verbal dictation into the EMR,” he explains. “We spent time exploring having this dictation picked up by a microphone, and then a technician who wasn’t necessarily physically with me would have access to the EMR that I was looking at and would populate that EMR in real time. That actually worked pretty well. For our group, with the way it was set up, that wasn’t something we necessarily chose to continue, but I know other groups who have and found it to be successful.”

|

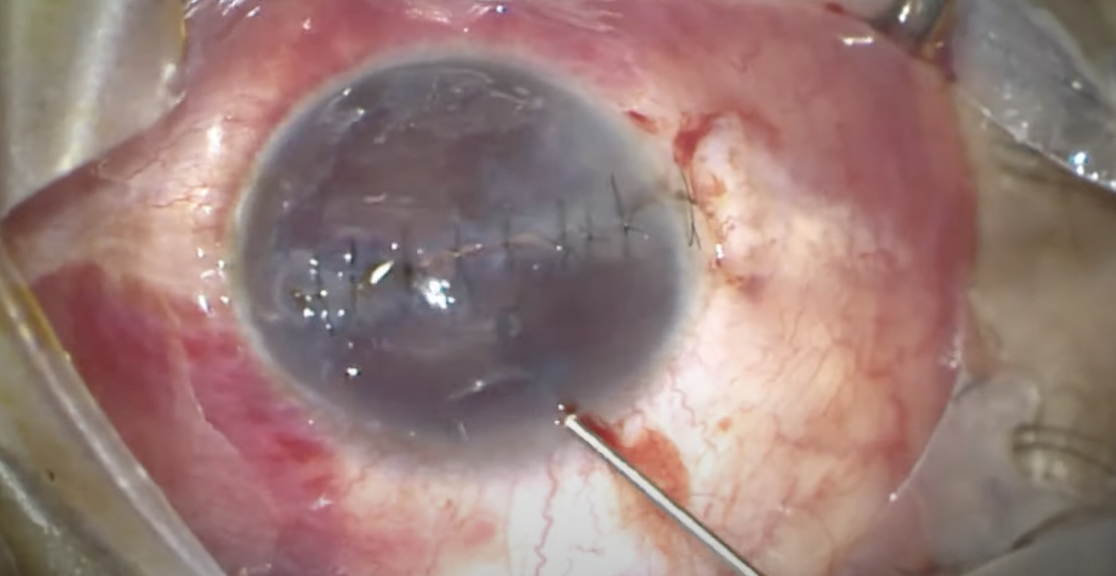

| Telemedicine was employed for emergency department triage and follow-up during the pandemic. Above, a resident surgeon repairs a ruptured globe that presented to the ED. (Courtesy Uday Devgan, MD). |

Like many retina specialists, glaucoma specialist Michael V. Boland, MD, PhD, of Massachusetts Eye and Ear, reports that his practice “was never a huge user [of telemedicine], even during the pandemic. We found it challenging to get everything done that we wanted to. Patients came in for testing anyway. All of our glaucoma patients are being seen in-person at this point.”

Telemedicine was somewhat more useful in anterior segment subspecialties. Cornea specialist Gaurav Prakash, MD, of Pittsburgh University School of Medicine, says that his practice was pushing virtual care during the pandemic for routine cases, but now it’s dropped down significantly. “Each provider has his or her own comfort levels, but I’m more in favor of clinic visits,” he says. “There’s been a substantial decrease [in our usage of telemedicine] although we still have telephone calls to circle back with the patient regarding things. We used to have testing off site, and then we’d review those results with the patient. We also followed up non-sight-threatening issues such as improving conjunctivitis.”

“When we were shut down for COVID and then ramping back up, I did a decent amount of telemedicine with patients,” says cornea, cataract and refractive specialist Evan Schoenberg, MD, of Georgia Eye Partners in Atlanta. “There was a lot of interest in exploring options and getting the ball rolling. I found virtual visits relatively useful for educating. You could do a lot just by understanding what a patient’s glasses prescription was and talking with them about their potential options based on their refraction and their age. Then patients would come in for the actual consultation pretty ramped up and raring to go in terms of knowing what they thought they wanted and knowing there was a potential option at least.

“In the last year, I’ve done almost no telemedicine though,” he continues. “We’re a very busy in-person clinic and I just don’t have a block of business hours that I want to set aside for seeing patients to do telemedicine myself.”

In neuro-ophthalmology, a study of 159 patients found that 65.4 percent were satisfied with their virtual visit, 93.7 percent said they felt comfortable asking questions and 73.9 percent found the instructions given before the visit easy to understand.1 More than 87 percent of neuro-ophthalmologists in the survey reported that they were able to perform a virtual examination that provided sufficient information for medical decision-making. Testing range of eye movements, visual acuity, Amsler grids, Ishihara color plates and pupillary exam were reportedly easy to conduct, while other examination components were more challenging, such as saccades, red desaturation, visual fields, convergence, oscillations, ocular alignment and smooth pursuit. Vestibulo-ocular reflex, VOR suppression and optokinetic nystagmus were very difficult to test. As with most subspecialties, the inability to perform a fundus examination was a significant limitation.

Best Tele-Scenarios

Experts say that patients who are likely to benefit from telemedicine are established patients and those who are fairly stable but still need additional follow-up to ensure their conditions aren’t progressing. “For example,” says Philip Dockery, MD, MPH, of the Harvey and Bernice Jones Eye Institute, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Little Rock, “it’s beneficial to see a patient with keratoconus in person for the initial evaluation, particularly if they require cross-linking, but subsequent visits after the initial follow-up period could be done by telehealth visits where the patient comes in for imaging to ensure there are no changes in their corneal tomography, and then we review those results with the patient virtually. Similarly, a post-transplant patient with Fuchs’ dystrophy might also come in for imaging to ensure there are no areas of edema or graft detachment, followed by a virtual visit.”

“Anything where it’s purely a discussion could be suited to telemedicine,” Dr. Boland adds. “Perhaps something that’s been discussed before or about changing a medication, or moving on to surgery, where we just need to talk about it without performing an exam for additional information. Those types of visits were easy, and those were things we could do even now. I think it’s just hard to work in the virtual visits inside of an otherwise in-person clinic.”

One of the more promising areas of ophthalmic telemedicine is emergency department triage2 and follow-ups. “One area where I’m doing telemedicine is helping out with our emergency department,” says Dr. Boland. “Patients with non-urgent eye issues who need follow-ups I see in virtual visits. I’m currently following up on corneal abrasions, subconjunctival hemorrhages, dry eye and foreign body removal—things that just need a follow-up to confirm that symptoms have resolved and to make sure there are no other questions from the patient after their initial visit.”

Dr. Boland says red-eye symptoms and pain are among the most common presentations at the emergency department, but “a number of things can cause a red eye. Some are vision-threatening, and others are totally benign. It’s hard to tease those apart. A subconjunctival hemorrhage is usually the one thing you can figure out, but if it’s a bloodshot eye that could have any number of causes.”

Dr. Schoenberg says he’s thought about hiring a refractive counselor or having one of his optometric team do a half-day of refractive telemedicine consults, since the infrastructure is available now. “We might launch that in the future, but I’m not doing it at present,” he says. He envisions these consults as potentially coming from online leads, such as his practice’s website or an online quiz. “People might be able to self-schedule a 15-minute telemedicine consultation about [refractive] options, and then that would potentially be a lead into scheduling an in-person consultation. It could also be used as a discussion point for patients who are referred from other doctors in the community, but usually those doctors are doing education in their offices before we get to them.”

If you’re expecting a potential treatment may be warranted that day or it’s the patient’s initial visit, an in-person evaluation is the best option, according to Dr. Dockery. He says, “You can get a better view using a slit lamp and do a complete workup, meet the patient, develop better rapport in person, and then do the initial diagnosis and any sort of treatment or management.”

He emphasizes the importance of multimodal imaging, such as slit lamp imaging, anterior segment OCT and corneal tomography, which offer a better picture of what’s going in. “There’s not really a great form of imaging that can replace an in-person slit-lamp exam,” he says. “Even two-dimensional slit-lamp photography is just that—two dimensional. You’re limited in your ability to discern the location or depth of certain lesions or areas of concern.”

Dr. Prakash agrees. “Overall, virtual care depends on the investigative capabilities we have,” he says. “I’d rather see a patient in person who’s mission-critical in terms of losing vision than to see them remotely, because obviously, it’s contingent on the quality of the camera and illumination. Cornea is very visual. Telemedicine may be useful for certain scenarios, but I don’t see it replacing or taking a significant chunk away from cornea, as such.”

Reduced Patient Burden

“Many offices were looking for ways to continue to see patients even when they were trying to keep their in-person workload down to reduce the number of patients in the clinic and allow for social distancing,” says Dr. Dockery. “During that time, I think many providers realized that the telemedicine platform allows for you to see many patients, particularly routine patients, in an efficient way—often remotely, where they don’t need to come into the office.”

He says telemedicine’s role in minimizing the travel burden some patients face can be significant. “Many patients really enjoy it because it limits their travel and they’re able to stay closer to home. They don’t have to go into a large city or navigate a parking deck or fight traffic. They don’t have to wait nearly as long in the clinic. Usually, at remote imaging pods or centers, they’re able to get in and out very quickly, so patients enjoy it and they’re almost able to do it on their own time.”

“I think there’s likely to be an increasing demand from patients for communication on their own timeframes,” says Dr. Schoenberg. “The ‘do it now’/Uber Eats world where you sit at home and things come to you isn’t going to go away anytime soon. I wouldn’t be surprised to find that we end up expanding telemedicine in the future. I know there are practices that have been doing it pretty successfully and seeing good benefits from it. I don’t think that it’s going to be a must for every practice, but I think in some environments and some patient populations, it’ll be a big piece of patient care eventually.”

Studies report that young people, those who would otherwise miss work and those who are familiar with video conferencing and internet use, are more likely to be interested in ophthalmic telemedicine services.3 Experts say that practices looking to increase their telemedicine usage could target these populations.

But while telemedicine can help overcome some patient barriers such as travel, experts caution against telemedicine’s potential to exacerbate existing inequalities. Many living in rural regions are still without access to high-speed Internet. Historically marginalized populations were less likely to receive ophthalmic telemedicine care vs. in-person care during the first year of the pandemic, according to a retrospective, cross-sectional study at Massachusetts Eye and Ear.4 The study also found that older patients, men, non-English speakers, those with an educational level of high school or less and those who identified as black used telemedicine less; and video-based visits were underutilized by older patients and patients who were retired, disabled, unemployed or had a high school education level or less.

Time is Money

While telemedicine seems to save patients time, the same can’t be said for all practices. “I’ve found that virtual visits take longer,” says Dr. Boland. “By the time you get [the camera] set up and the patient sets up theirs, you could have had that conversation more quickly just going room to room in the clinic as opposed to getting everyone’s video cameras working correctly and connected. It’s just proven easier to have these conversations in the clinic, especially given that the patient already has to come in for testing. They might as well talk to me right now about the result. We’ve started scheduling testing on the same day but slightly in advance of my visit, so that helps keeps things flowing pretty smoothly.”

Dr. Boland says an interactive messaging back-and-forth without a video component could be useful. In this scenario, the doctor might call the patient to tell them about their test results—“ ‘they look the same and we’ll see you in however many months’—and avoid the whole in-person encounter altogether.”

With the current state of telemedicine, time really is money. Though Dr. Garg says reimbursement for virtual care itself during the pandemic wasn’t an issue, “what we found is that, after all the time and effort of setting up the appointment, getting logged on, figuring out technical difficulties, sitting there, asking the patient questions, waiting for them to respond—the number of patients we could reasonably interface with in an hour was comparatively low compared to what we’re used to doing in retina, too low for us to continue to function that way. Our practice is structured around seeing a certain number of patients, given all the equipment costs, large personnel costs, exam space and other high fixed costs. Unless our primary model were telemedicine, where the practice would have very low staffing and a small-footprint office, it wouldn’t be sustainable. We’d have to radically rethink the delivery of care in order for that to work.”

Dr. Schoenberg recalls a similar barrier. While his practice was able to bill virtual visits as if they were in-person visits, thanks to the emergency changes in billing during the pandemic, he says, “I didn’t feel that it was a large enough volume to move the needle as a whole practice for the time we were doing it, but it definitely was nice not to be sitting at zero when we were at home and not seeing patients.”

Remote Monitoring

Dr. Garg says that once at-home OCT devices (e.g., Notal’s investigational AI-enabled Home OCT or the ForeseeHome monitoring program) become more widely available to patients that “will be a step closer to an ability to assess the retina, though home OCT will only allow us to look at the central part of the macula, so it’s not going to be great for a lot of what we do, though it’ll be helpful.”

Dr. Boland’s practice sets up certain patients with the iCare Home device to monitor pressures outside of clinic hours. He says it’s helped confirm some findings and that they’ve found a number of patients with pressures too high at times they’re never in the clinic. “We never would have found those late night and early morning pressure increases, so it’s been helpful,” he says. “I think making it more cost-effective for patients would be great.”

As for home visual field monitoring, while there are several portable perimetry devices from various companies now, “most or all of them don’t have any normative data, so we can’t really make diagnoses based on the test.” Dr. Boland says. “They certainly don’t have longitudinal data either, so we can’t identify worsening disease over time. I think as those devices mature, the hope would be that more patients can use them at home. Then they wouldn’t have to come in as much for testing with us.

“The challenge with home monitoring is going to be synthesizing all of this data coming in from outside,” he continues. “I have all these new pressure values—what do I make of all this? AI and machine learning algorithms might help us digest all this information to make more efficient decisions. It’s also not always clear that we can bill for this service. Sometimes we can; sometimes we can’t. There needs to be payment models so patients can use these devices at home long-term, but we haven’t worked those out yet, as well as workflow models. We also need better ways of getting the data back into the clinic, so better standards for transmitting home visual fields or home eye pressures to the clinician would be really important.”

“There was a lot of hope during the pandemic for telemedicine being used more extensively,” Dr. Boland adds. “I think we’re still up against a lot of the same challenges—not being able to get testing or do a real exam—so there are some concerns about misidentifying and misdiagnosing patients without all that information. But I think there’s some hope that newer home-based technologies might be able to do more going forward.”

Reducing Unnecessary Referrals

Dr. Han says that in the “post-pandemic” era, there’s been a shift of referral patterns in his area, particularly for comprehensive and general ophthalmology practices. “Several experienced retina specialists in our area have retired, and many local practices have started to refer routine retinal problems and procedures (e.g., intravitreal injections) to our subspecialty clinics. This has resulted in a marked rise in volume in our department, including many cases that may not require retinal specialty evaluation (e.g., diabetic retinopathy screening).

“Early on, a common fear with the emergence of telemedicine and AI-based retinal screenings was that these technologies might replace or obviate the need for retina specialists,” he continues. “However, with our current higher patient volume, relative scarcity of resources (e.g., short staffing in the clinic after the pandemic-associated ‘great resignation’), and increasing treatment burdens (e.g., from intravitreal injections, including new drugs for geographic atrophy for dry AMD), one key potential advantage of telemedicine is to assist with screening visits (e.g., for diabetic retinopathy) to decrease the overall volume of unnecessary referrals, thus allowing space for those patients who truly need subspecialty care.

“Modern retina care typically requires high-quality imaging to screen for disease or guide treatment decisions,” says Dr. Han. “Some barriers to adoption remain the lack of widespread availability of such technology, though innovative researchers, such as our colleague Michael Abramoff, MD, PhD, have made tremendous progress in recent years toward implementing AI-based pathways for screening.”

A Cautious Step Forward

“We’re still a bit constrained with the adoption of telemedicine,” says Dr. Garg, “but over the next few years, I think we’ll have more pieces in place that will make telemedicine potentially more useful for more of our patients.”

Dr. Prakash emphasizes the need for balanced approaches with telemedicine. “We want to make sure that by doing telemedicine, we’re not compromising the quality of care for the patient,” he says.

Drs. Dockery, Prakash, Han, Garg, Boland, and Schoenberg have no related financial disclosures.

1. Conway J, Krieger P, Hasanaj L, et al. Telemedicine evaluations in neuro-ophthalmology during the COVID-19 pandemic: Patient and physician surveys. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology 2021;41:3:356.

2. Meshkin RS, Armstrong GW, Hall NE, Rossin EJ, Hymowitz MB, Lorch AC. Effectiveness of a telemedicine program for triage and diagnosis of emergent ophthalmic conditions. Eye 2023;37:2:325-331.

3. Shiuey EJ, Fox Y, Kurnick A, Rachmiel R, Kurtz S, Waisbourd M. Integrating telemedicine services in ophthalmology: Evaluating patient interest and perceived benefits. Patient Prefer Adherence 2021;15:2335-2341.

4. Aziz K, Moon JY, Parikh R, et al. Association of patient characteristics with delivery of ophthalmic telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Ophthalmology 2021;139:11:1174-1182.