“When it comes to infection prophylaxis, there isn’t evidence that topical agents are effective,” says Samuel Masket, MD, who is in private practice at Advanced Vision Care Los Angeles and a clinical professor of ophthalmology at the Jules Stein Eye Institute, UCLA. “Moreover, patients often instill drops incorrectly. And, with medications that need to be used as frequently as four times a day, compliance drops off. Also, some patients are sensitive to the preservatives, particularly if they have been on medication a long time. Some patients develop punctate keratopathy, which impacts negatively on comfort and vision. I think all of us realize that there are problems with drops. Another frequent annoyance occurs at the pharmacy if branded meds are switched by the pharmacist for a generic eye drop or if the patient’s insurance doesn’t cover a given medication. This alone is a thorn in our sides and reason enough to move away from eye drops.”

One option is to inject the medications instead of instilling them topically. “Injecting drugs ensures delivery of the medicine, and it’s a great convenience to the patient,” says Neal Shorstein, MD, an ophthalmologist and associate chief of quality at Kaiser Permanente in Walnut Creek, Calif. “In a recent study, when elderly patients were videoed trying to put in the drops, there was a high incidence of failure to instill the drops correctly and with good hand hygiene, and I worry about that.”

The Canadian study found that cataract patients who were inexperienced with eye-drop use demonstrated poor instillation technique by failing to wash their hands; contaminating bottle tips; missing their eye; and using an incorrect amount of drops.1 The study included 54 patients. Subjectively, 31 percent reported difficulty instilling the eye drops, 42 percent believed that they never missed their eye when instilling drops, and 58.3 percent believed that they never touched their eye with the bottle tip. Objectively, 92.6 percent of patients demonstrated improper administration technique, including missing the eye (31.5 percent), instilling an incorrect amount of drops (64 percent), contaminating the bottle tip (57.4 percent), or failing to wash hands before drop instillation (78 percent).

Injections

Additionally, a growing body of evidence is showing that intraocular administration of antibiotics is safe and effective for infection prophylaxis.

|

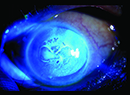

“Since that investigation, I’ve used 0.05 mL nondiluted Vigamox right out of the bottle in every cataract case, and I have not noted any toxicity,” says Dr. Masket. “That study did not address efficacy owing to the larger number of necessary cases, but we found that intracameral Vigamox was not toxic when masked against BSS with regard to corneal edema, endothelial cell counts, anterior chamber inflammation and macular edema.”

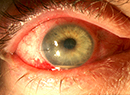

Dr. Shorstein and colleagues at Kaiser Permanente in California found that intraocular administration of antibiotic is more effective for preventing postoperative endophthalmitis than topical antibiotic.3 In their study, they identified 315,246 eligible cataract procedures performed at Kaiser between 2005 and 2012 and confirmed 215 cases of endophthalmitis (0.07 percent). The researchers found that intracameral antibiotic was more effective than topical antibiotic alone for preventing endophthalmitis; and they found that combining topical gatifloxacin or ofloxacin with an intracameral agent was not more effective than using an intracameral agent alone.

“The problem as I see it, however, is that presently we don’t have an appropriate delivery system to include anti-inflammatory as well as anti-infective prophylaxis,” Dr. Masket says. “The injection of a long-acting intraocular steroid may induce elevated intraocular pressure. I look forward to the day when we have delivery systems that can emit low-dose medication over a long period of time to manage the anti-inflammatory component of postoperative treatment. I believe that it needs to take the form of both a steroid and a nonsteroidal agent because there is strong evidence that NSAIDs are more effective at preventing cystoid macular edema than are steroids.”

Currently, Dr. Masket uses 0.05 mL of Vigamox intracamerally in every eye, and he continues to use topical agents as well. “I am very much in favor of the concept of moving away from drops, but I am awaiting newer delivery methods. In the near future, our office will be participating in an investigation of a combination of injected dexamethasone and moxifloxacin at the time of surgery, combined with a topical NSAID postoperatively,” he says.

Other surgeons are comfortable injecting both anti-inflammatory and anti-infective agents postoperatively. Dr. Shorstein began injecting antibiotics in 2008. “Once we had set up onsite compounding with our integrated pharmacy at our surgery center and felt comfortable injecting it, we then took the next step of stopping perioperative antibiotic drops because we felt that there really wasn’t any strong evidence in the literature that they reduce the rate of endophthalmitis,” he says. “Given the strong evidence for intracameral antibiotics, we didn’t feel that topical drops added any substantial benefit to intracameral antibiotic injection. After all, we are injecting right into the space where one would want to have the antibiotic. In the latter half of 2008, we began to think about an alternative delivery of corticosteroid to prevent postoperative macular edema. There were a couple of articles in the literature showing the effectiveness of injected triamcinolone subconjunctivally, and we started doing that in late 2008.”

A few months ago, Dr. Shorstein published a study that examined the relationship between chemoprophylaxis and the occurrence of acute, clinical, postoperative macular edema.4 The study included 16,070 cataract patients who underwent phacoemulsification at Kaiser Permanente between 2007 and 2013. There were 118 confirmed cases of macular edema. The study found that adding a prophylactic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug to a postoperative topical prednisolone acetate treatment was associated with a reduced risk of macular edema with visual acuity of 20/40 or worse. The risk and safety of triamcinolone injection were similar to those of topical prednisolone acetate alone.

“An interesting and somewhat surprising finding was that the patients who were treated with a topical NSAID in addition to topical prednisolone had half the rate of macular edema,” says Dr. Shorstein. “We looked at over 16,000 eyes, so this is one of the very few large studies that has shown a statistical difference in the reduction of macular edema with an NSAID. Those of us who were injecting the triamcinolone began asking if we should be adding NSAID drops routinely for patients who undergo phacoemulsification. Interestingly, only 0.73 percent of our group’s phacoemulsification eyes were diagnosed with clinically relevant, OCT-validated macular edema. That’s a small percentage. We felt that, given the overall low incidence of macular edema and given that it’s a fairly benign complication of phacoemulsification cataract surgery, we didn’t see a compelling reason to alter our dropless, intracameral antibiotic injection practice.”

He adds that, if dropless administration is equally effective and sufficient, surgeons may be doing patients a favor by reducing the risk of endophthalmitis by limiting the manipulation of the eye after surgery. “It is a few dollars per eye to compound the intracameral antibiotic. The pharmacy prices for late-generation fluoroquinolone drops could run several hundred dollars a bottle,” Dr. Shorstein says.

| A Different Take on Going Dropless |

| Omidria (phenylephrine and ketorolac injection 1%/0.3%) can be added to irrigation solution preoperatively and is the only Food and Drug Administration-approved product for intraocular administration that prevents intraoperative miosis and reduces postoperative pain. In a recently published study, it was found to maintain mydriasis, prevent miosis and reduce early postoperative pain when administered in irrigation solution during intraocular lens replacement, with a safety profile similar to that of placebo.1 According to Robert Weinstock, MD, many of the challenges that surgeons face during cataract surgery are related to intraoperative pupil size and maintaining good visualization during surgery, and inflammation after surgery. “Omidria is a combination of a dilating agent and a nonsteroidal and has a dual mechanism of limiting inflammation and maintaining dilation of the eye,” says Dr. Weinstock, who is in practice at the Eye Institute of West Florida in Largo. “It allows the surgery to go more smoothly because the pupil stays larger during the case. This is extremely important in patients who have had previous laser peripheral iridotomies and glaucoma and in patients who are taking alpha-2 antagonist medications for urologic or cardiovascular conditions, because these are the patients who develop floppy iris syndrome intraoperatively.” Johnny Gayton, MD, of Eyesight Associates in Warner Robins, Ga., says, “Omidria is a novel way of delivering a nonsteroidal. No other product, compounded or commercial, offers an intraocular nonsteroidal. The nonsteroidal, in combination with phenylephrine, a very potent dilator, helps us a great deal in maintaining the pupil during cataract surgery. It is well-known that if the pupil drops below 6 mm during cataract surgery, visualization decreases, your surgical time increases and your complication rate increases.” He notes that Omidria is also beneficial in femtosecond laser cases. “This product offers us an incredible tool to help us maintain patients’ pupils with both traditional and femtosecond-assisted surgery and to help control patients’ discomfort during and after the procedure,” Dr. Gayton says. Omidria was approved by the FDA in 2014. Dr. Weinstock says that he is only using Omidria in select patients currently, because it is not covered by all insurance companies. “The number of patients in my practice who are receiving Omidria is growing because insurance coverage is just getting ramped up,” he says. “As more insurance plans are starting to cover this, we will expand our usage. I will consider using it in all patients who have insurance coverage, because you never know who is going to have floppy iris syndrome. I’m in favor of anything we can do safely to help that pupil stay dilated.” —M.S. 1. Lindstrom RL, Loden JC, Walters TR, et al. Intracameral phenylephrine and ketorolac injection (OMS302) for maintenance of intraoperative pupil diameter and reduction of postoperative pain in intraocular lens replacement with phacoemulsification. Clinical Ophthalmology 2014;8:1735-1744. |

“Less Drops”

However, some surgeons are reluctant to give up drops completely. “Dropless injectable antibiotic/steroid combinations are a great idea, attain good results and may be especially useful in non-compliant, physically challenged and/or indigent patient populations. However, there are four difficulties with this approach,” says Lance Ferguson, MD, who is in private practice in Lexington, Ky.

Dr. Ferguson cites the challenges and the drawbacks to injection:

• Technique. “Although there is a short learning curve, the surgeon must be able to get an adequate dosage into the vitreous cavity via a trans-zonular approach or be comfortable with pars plana injections,” he says.

• Floaters. With refractive cataract surgery, the immediate “wow” factor has become increasingly more important to patients and as a practice builder through word of mouth and social media, and the prednisolone stranding is bothersome to many patients. “Good preoperative counseling, controlling expectations, and patient selection will help, but when patients are still struggling in the first week and their drop-using friends extol their immediate great vision, patients sometimes forget this preoperative session. Moreover, that session takes time and staff hours,” he adds.

• Edema. “Even with great delivery, an occasional patient will need supplemental steroid/NSAID drops, and this again can be addressed preoperatively. However, the reality of expensive drops in addition to the injection (that they paid for) will be a sore spot for many patients, and they will wonder why they elected for the dropless approach when they ultimately need and pay for ‘additional’ drops. Again, this is a time sink for staffers and makes these patients less than enthusiastic ambassadors for the dropless approach,” he explains.

• Depot medicine. “Once onboard, the steroid cannot be withdrawn, which presents patient safety and medicolegal issues, particularly if the patient is far away from the practice and has difficulty visiting even a comanaging optometrist/ophthalmologist. If the patient is a steroid responder, then many additional visits, meds, expense, and family inconvenience will be required for IOP control. With drops, the medication is simply discontinued, and the problem resolves,” he says.

Dr. Ferguson’s practice uses the “less drops” approach espoused by Imprimis. They compound antibiotic/steroid drops or antibiotic/steroid/NSAID drops and find them particularly appealing to a wide range of patients. “Less drops patients enjoy the convenience and cost savings (we mark up the cost of these meds only about 5 percent) of obtaining their drops at the practice site, precluding pharmacy stops, hassles and insurance issues,” he explains.

Additionally, Dr. Ferguson says that there is a simpler schedule and ease of administration, adding up to improved patient compliance—only one bottle, four times a day, with a scheduled taper, and there is safety in the event of an untoward reaction to any of the components.

Also, there is no potential for disappointment, because patients understand from the start that they will need to use the drops for three to four weeks postoperatively.

“Practices who use the ‘less drops’ approach enjoy markedly less counseling, paperwork permits and staff time consumed with dealing with pharmacies, unavailable meds and generic-only substitutes, etc,” Dr. Ferguson believes. “And they have happy patients who share their positive (and simpler) experience with others.”

Additionally, according to Dr. Ferguson, there is less medicolegal risk in the event of a steroid responder or possibly a patient with a retinal complication (which, although unrelated to the injection/pars plana injection, may, in the patient’s mind, be forever related).

“The ‘less drops’ program has really helped us,” he says. “It is much less expensive for patients, and it is much simpler for them from a compliance standpoint. I’m very happy with this new compounding. And let me reiterate, because it provides the option of discontinuing or altering components, it avoids the risks of depot medicine. I don’t take boats into harbors that I can’t get them out of.” REVIEW

1. An JA, Kasner O, Samek DA, Levesque V. Evaluation of eyedrop administration by inexperienced patients after cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2014;40(11):1857-1861.

2. Lane SS, Osher RH, Masket S, Belani S. Evaluation of the safety of prophylactic intracameral moxifloxacin in cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34(9):1451-1459.

3. Herrinton LJ, Shorstein NH, Paschal JF, et al. Comparative effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis in cataract surgery. Ophthalmology. 2015; October 9 [Epub ahead of print].

4. Shorstein NH, Liu L, Waxman MD, Herrinton LJ. Comparative effectiveness of three prophylactic strategies to prevent clinical macular edema after phacoemulsification surgery. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(12):2450-2456.