Resident cataract surgery training has transformed over the last several decades.1,2 Trainees are steeped in fast-paced, technologically advanced surgical environments with high attending expectations and even higher patient expectations. Today’s cutting-edge, minimally invasive cataract surgery is a far cry from the overnight hospitalizations of the past.3 Now, rapid visual recovery and precise refractive outcomes are expected and even demanded.4,5

In the face of such high stakes, it’s common for residents to feel the pressure of perfection, despite the fact that we’re still learning these techniques. So, as trainees, how do we maximize our potential, safely acquire skills and judgment, and carefully push boundaries while minimizing errors to deliver excellent surgical outcomes?

I believe the answer lies in trust—earning the trust of the attending surgeon. The question then follows: How can we do this?

Trust is Key

The attending-resident relationship is paramount; however, to date, little attention has been given to how residents can contribute to forging such relationships.6 The foundation of surgical training is mutual trust between the resident and the attending, who’s shouldering the responsibility for excellent patient outcomes.7 Attendings have had diverse experiences operating with residents. Often at the forefront of an attending’s mind is “that one surgery” with a resident where there were issues. From complications to insubordination, from lack of preparation to arrogance, most seasoned attendings can readily recall a resident experience they wish to never repeat. As residents, we don’t want to be “that one surgery.”

Instead, we should strive for competence by cultivating a trusting relationship with the attending through openness to advice and constructive criticism, attention to detail and respect. These practices begin before entering the operating room.

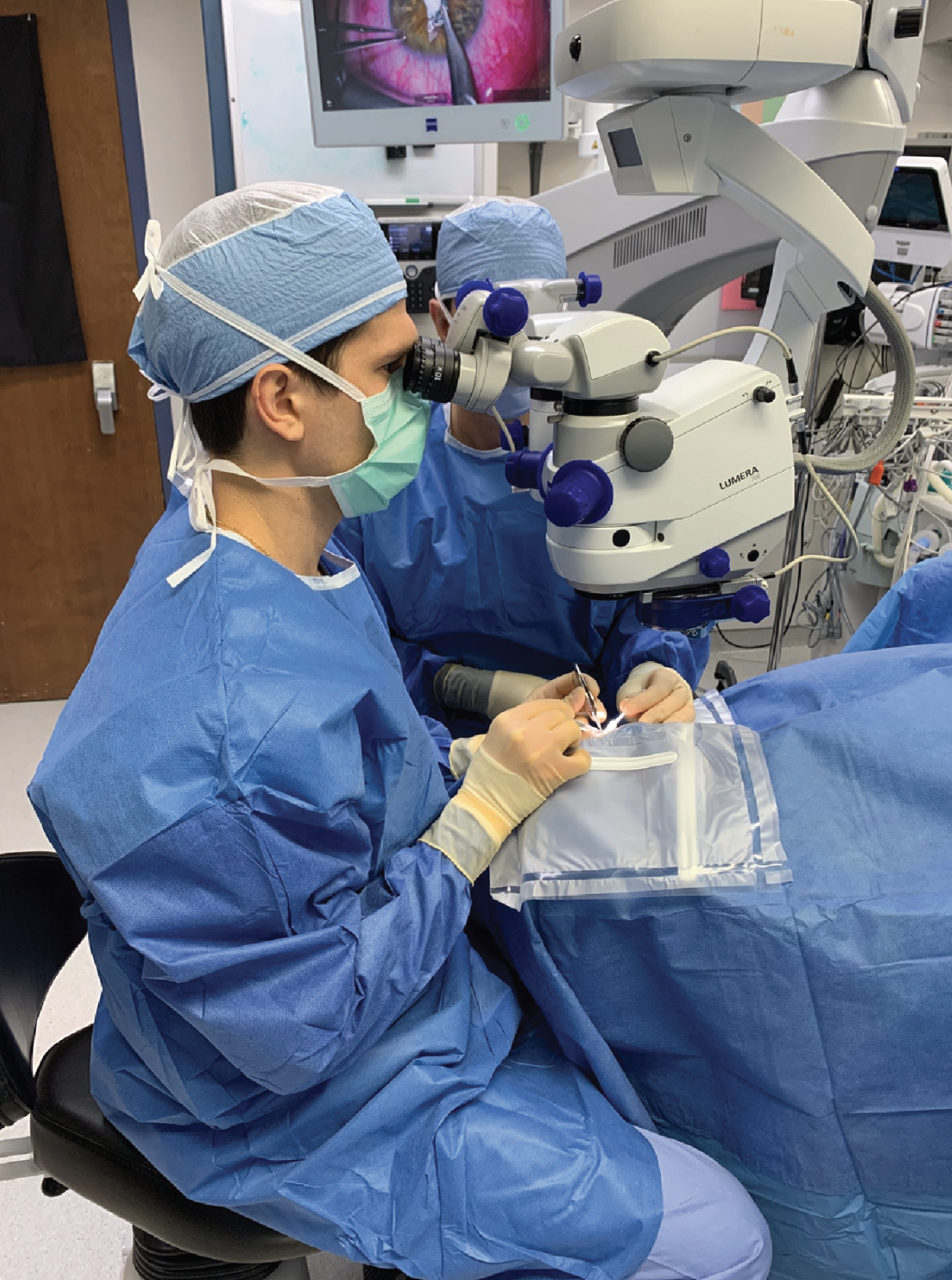

|

| Figure 1. Resident surgeon (seated superiorly) being guided through the repair of a ruptured globe by an attending surgeon (seated temporally). |

Foundational Learning

As the saying goes, “you play like you practice and practice like you play.” Before entering the operating room, residents must have both an intellectual and a mechanical understanding of cataract surgery. The intellectual component can be found in textbooks, anatomical diagrams, online surgical videos and articles, and academic discussions. We’re fortunate today to have easy access to YouTube channels dedicated to surgical development. These channels have revolutionized training, transforming small residency programs into international classrooms of the highest caliber. It’s here residents can encounter cataract surgery in a risk-free environment.

Although low stakes, this may be one of the most important components in laying a sturdy surgical foundation. As you know, when reading, watching surgical videos and participating in discussions, we have to be fully present and engage with the information critically and actively as opposed to passively absorbing it. It might be more useful to watch surgical videos at 0.5x speed instead of 2x speed. Another thing to keep in mind while watching these videos is the anatomy and physiology we’ll encounter at each step of surgery. We can ask ourselves: Why was this movement executed in that manner? What are the consequences of forgoing this technique? Is there a more efficient movement to accomplish the same objective?

Linking such questions to the mechanical experience encountered in simulators and wet labs is invaluable.8-10 Deliberate, dedicated time in wet labs, both within and outside clinical hours, allows trainees to go beyond understanding techniques in a purely intellectual fashion to understanding them experientially. It’s here we can progress from what is done to how and why it’s done and acquire an introductory understanding of consequences and alternatives. Spending dozens or hundreds of hours working under a microscope helps to develop the dexterity required for intricate surgical procedures. Critically approaching intellectual and mechanical learning in this way promotes rapid surgical growth and prepares us to apply novel techniques in the future.

Preoperative Notes

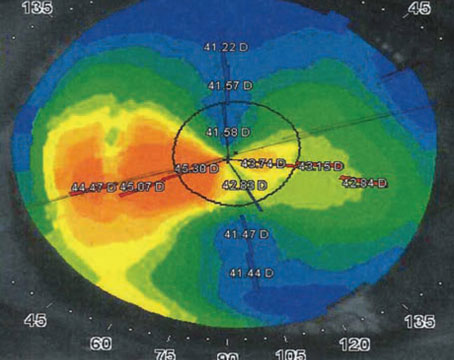

The pillars of the surgery process include the preoperative evaluation, actual procedure and postoperative course. Robust preoperative documentation is a key component in building attending trust. It gives the attending a window into the trainee’s thought process, offering an opportunity to demonstrate your preparedness.

Our goal for when the attending reads a preoperative note (and they will), is for the attending to feel peace of mind that the patient was thoroughly evaluated and that every concern was reasonably addressed. If a patient has a high prescription that will result in significant anisometropia after cataract surgery on the first eye, was this discussed with the patient? Were temporary mitigation techniques proposed? Was the need to perform surgery on the second eye clearly stated and did the patient voice understanding?

When an attending reviews the preoperative note, it should be readily apparent that the ways in which a patient’s surgery might deviate from routine were identified, discussed with the patient and documented appropriately. Documentation reflects your thought process and aids in the development of surgical judgment. It’s a tangible way to demonstrate attention to detail, thoughtfulness, competence and concern for the best interests of the patient. Furthermore, these discussions reassure patients they’re in capable, caring hands and inspire trust in residents, a critically important and often neglected element in the preoperative process.

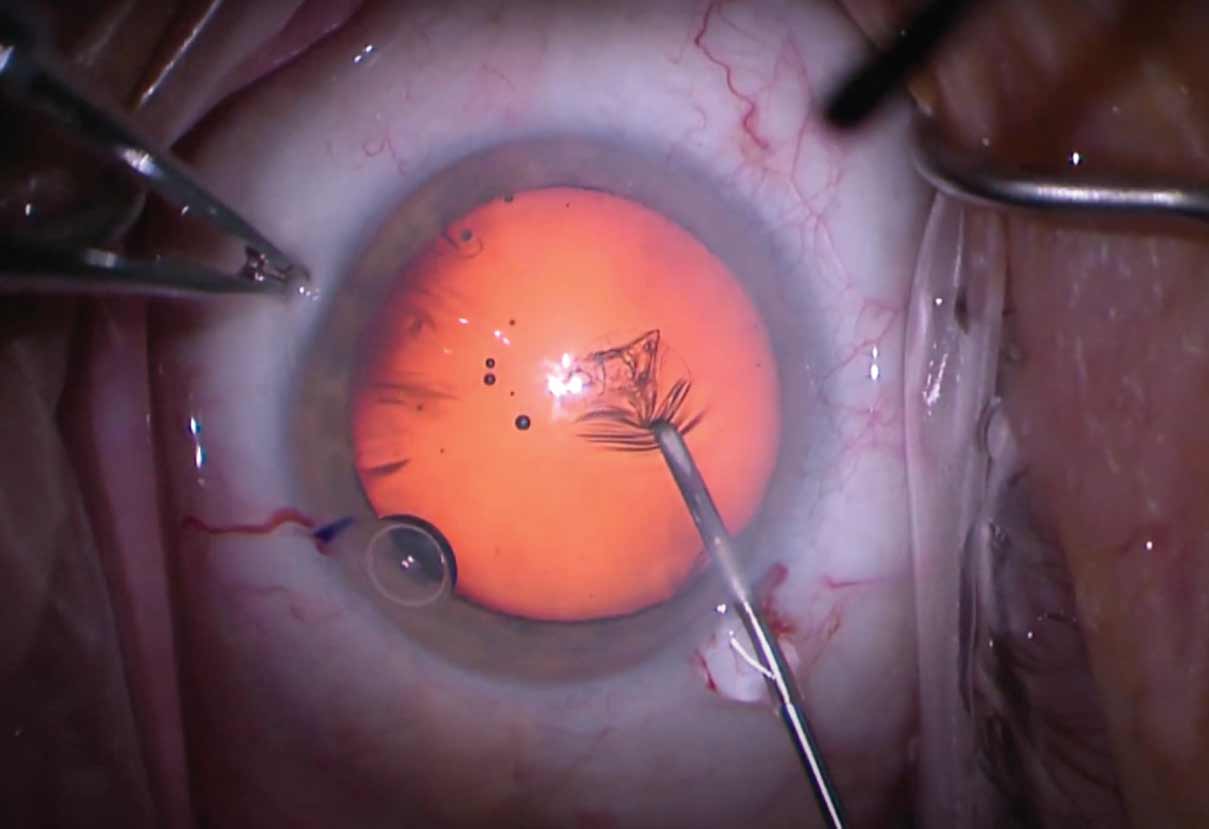

|

| Figure 2. Resident surgeon being guided through a capsulorhexis by an attending surgeon using a cannula on a bottle of balanced salt solution (seen in top right). |

In the OR

On the day of surgery, arriving calm and collected sets the stage for a smooth surgical day. To get off on the right foot, arrive early. Greet the team and learn their names. Check and adjust the microscope for proper comfort and optimal visual clarity both on the microscope and video monitors. Discuss individual patient needs with the anesthesiologist and operating staff. Ensure ancillary equipment is readily available, such as intracameral capsular staining and iris expansion devices. Have patients’ information and lens selections clearly marked and separate from one another to avoid any potential mistakes—when an attending reviews these calculations with the resident, they’ll be reassured to see such organization. As residents, accomplishing these tasks can build a sense of composure while also instilling confidence in the attending, thus setting the stage for a great day in the operating room.

With all this said, in the operating room and under the microscope is where the rubber meets the road (Figure 1). Every moment under the scope is an opportunity to gain or lose attending trust, and an attending’s stress level can be palpable. Understanding this, it’s here that we must obey an attending’s every instruction and execute each step with appropriate caution and deliberation (Figure 2). By becoming cocky or cavalier, a resident will eventually slip and hear the dreaded “gasp” from the side scope, which should be an immediate indicator to back off and return to a place of caution.

On the Same Page

As the attending sees a trainee’s growth and the resident feels comfortable with a particular step of surgery, it’s appropriate to progress to more advanced techniques; however, you shouldn’t try to surprise your attending with an unexpected move. Prior to the surgery, it’s best to get attending approval to try a new technique. You could ask: “At this point, I feel comfortable with divide and conquer. If you’re comfortable as well, may I try stop and chop for the next patient? I’ve studied this technique and practiced it in the wet lab, and I feel prepared to do it.” As formal as this may seem, we have to remember that we’re guests in the attending’s operating room. Using this same approach, techniques beyond basic forms of nucleus disassembly can also be discussed and more readily explored, cultivating a dynamic learning environment.

At a minimum, at the end of each surgical day, trainees should seek feedback, whether good or bad, and implement it in a demonstrable way. It’s also helpful to record every surgery performed so you can go back and study the game-day footage in detail.

Ultimately, the goal is to find the sweet spot—where the attending is relaxed, and you’re performing safe surgery while appropriately pushing the boundaries. It’s here, in this sweet spot, that the greatest growth occurs, and everyone wins: Patients receive their expected excellent surgery, attendings operate and teach in a dynamic learning environment with competent and motivated residents, and we maximize our supervised surgical experience to the benefit of our patients both now and in the decades to come.

Oliver Filutowski, MD, is a PGY-4 ophthalmology resident at the University of South Florida in Tampa, Fla. He can be reached at oliver@filutowski.com. Aarun Devgan is a fourth-year neuroscience major at Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H.. He can be reached at aarun.devgan@gmail.com. The authors have no financial interests to disclose.

1. Tsou BC, Vongsachang H, Purt B, Srikumaran D, Justin GA, Woreta FA. Cataract surgery numbers in U.S. ophthalmology residency programs: An ACGME case log analysis. Ophthalmic Epidemiology 2021;29:6:688-695.

2. Rowden A, Krishna R. Resident cataract surgical training in United States residency programs. Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery 2002;28:12:2202-2205.

3. Ingram RM, Banerjee DM, Traynar MJ, Thompson RK. Day-case cataract surgery. The Lancet 1983;322:8346:383-384.

4. Hawker MJ, Madge SN, Baddeley PA, Perry SR. Refractive expectations of patients having cataract surgery. Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery 2005;31:10:1970-1975.

5. Pager CK. Expectations and outcomes in cataract surgery. Archives of Ophthalmology 2004;122:12:1788.

6. Park J, Ponnala S, Fichtel E, et al. Improving the intraoperative educational experience: Understanding the role of confidence in the resident-attending relationship. Journal of Surgical Education 2019;76:5:1187-1199. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2019.02.012.

7. Nemani VM, Park C, Nawabi DH. What makes a “great resident”: The resident perspective. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine 2014;7:2:164-167.

8. Henderson BA, Grimes KJ, Fintelmann RE, Oetting TA. Stepwise approach to establishing an ophthalmology wet laboratory. Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery 2009;35:6:1121-1128.

9. McCannel CA, Reed DC, Goldman DR. Ophthalmic surgery simulator training improves resident performance of capsulorhexis in the operating room. Ophthalmology 2013;120:12:2456-2461.

10. Henderson BA, Ali R. Teaching and assessing competence in cataract surgery. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology 2007;18:1:27-31.