|

|

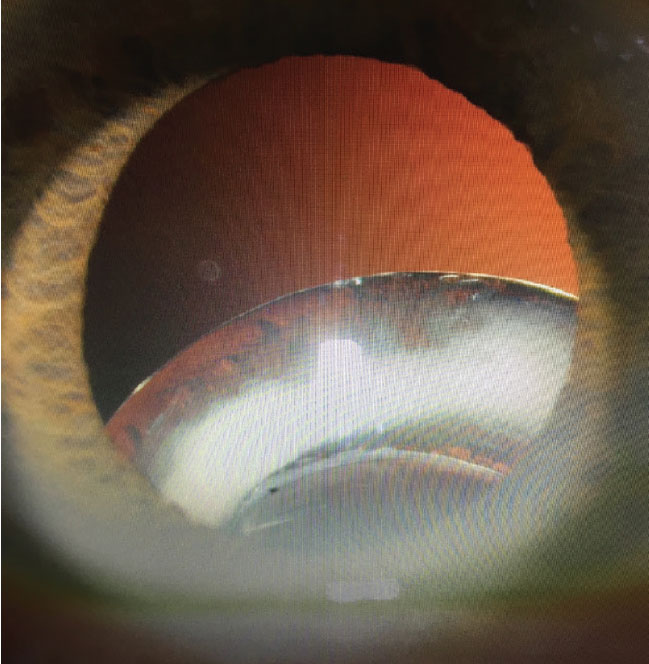

Inferiorly displaced IOL/capsular bag complex in a patient with pseudoexfoliation. |

Anterior and posterior segment surgeons are no strangers to surgical challenges involving displaced or subluxated IOLs, which have emerged as an epidemic of sorts in recent years. History has shown that when implants dislocate, and especially when they fall back into the vitreous cavity, they are best managed by entering the anterior vitreous cavity through the pars plana. Due to their unfamiliarity or discomfort with pars plana vitrectomy, anterior segment surgeons typically refer cases involving this specific need to a vitreoretinal surgeon. I, along with other anterior (CI, TT) and posterior (SO) segment colleagues, believe this method has some inherent limitations and have begun advocating for a new frontier: middle segment surgery (MSS), a domain where the requisite skills needed to perform these complex surgeries safely, with best visual and structural outcomes, comes first and foremost. Most importantly, this frontier is not limited to the anterior segment surgeon, but rather to the anterior OR posterior segment surgeon who has specifically honed their training and upskilling to be able to safely manage these cases on a regular basis.

Personal Experience

While serving on the Cornea Service at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia for three and a half decades, I simultaneously ran a consultative surgical private practice 25 miles away and have frequently had dislocated IOLs referred to me. For the first half of my career, the management strategy for these cases was the same: contact the retina service and perform a combined procedure where the vitreoretinal surgeon would explant the implant by entering the eye via the pars plana. After lens explantation, I would sclerally fixate a posterior chamber implant. The choice of intraocular lens, location and technique of fixation depended on several clinical factors and, importantly, good biometry. After several years, it became apparent that this approach had its limitations—it wasn’t efficient use of two surgeons’ time; we would frequently run into scheduling conflicts, leading to an unnecessary delay in patient care.

Many of us who are in private practice, or who perhaps aren’t associated with a large institution like Wills, may not have ready access to vitreoretinal specialists to help handle these cases using a team approach. Over a period of several years, with the help of like-minded vitreoretinal colleagues, I acquired the skill set to perform pars plana vitrectomies and the entire repair myself. Certainly, few if any anterior segment surgeons receive formal training in MSS during residency or fellowship. But much of what an ophthalmologist does in a 35- to 40-year career is evolutionary in nature. Most of us have had no formal training in what we do today.

Inevitably, there was significant pushback by our retina colleagues, who were adamantly opposed to anterior segment surgeons making any incision into the eye beyond 2 mm posterior to the limbus. Not looking for a turf war, I simply wanted to do what was best for patients and accomplish the repair with only one surgeon in one sitting, thus elevating the quality of care for my patients. In fairness, our retina colleagues argued that that goal was accomplished adequately by them and their services. As we all know, this led to thousands of unnecessary anterior chamber IOL implantations over the years.

Defining “Middle Segment Surgery”

The term “middle segment” has never been used officially. We know the anatomy of the eye and recognize the boundaries of the anterior and posterior segments. The middle segment is a zone 2 to 4 mm behind the limbus.

However, the anatomy is less important than the concept.

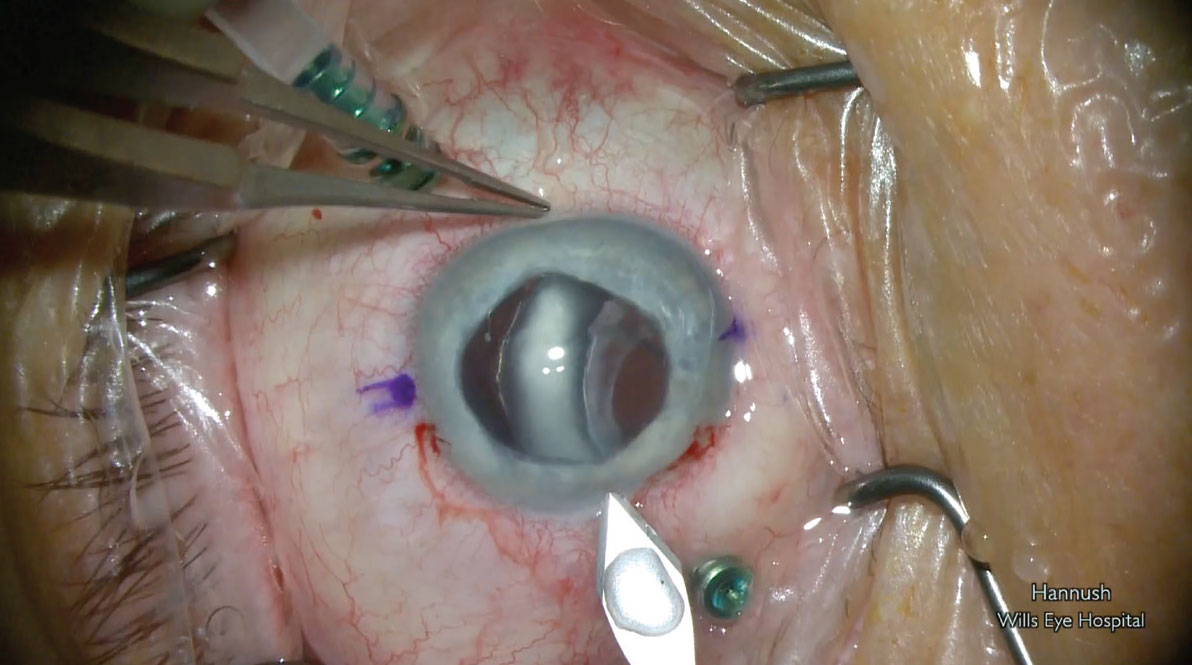

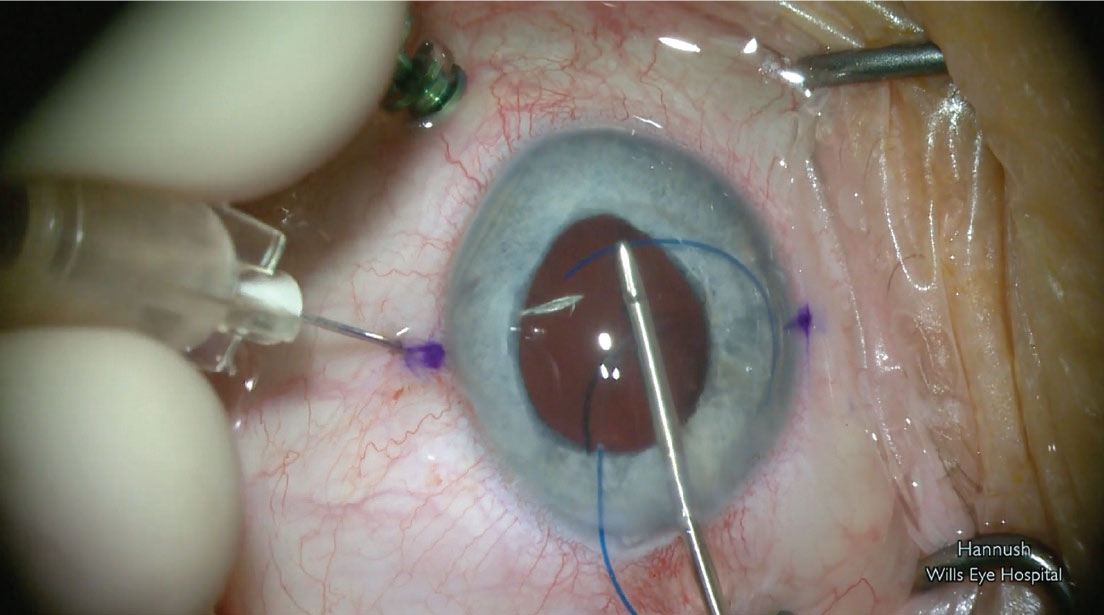

We firmly believe that the best way to solve the problem of dislocated implants is via a pars plana subtotal or total vitrectomy. A total vitrectomy may not be necessary and most frequently is not. Subtotal vitrectomy with emphasis on the trained, safe clearance of the anterior and core vitreous to allow for uneventful lens exchange with minimal/no tractional forces on the anterior retina is in order. After performing a safe subtotal pars plana vitrectomy and delivering the dislocated implant into the anterior chamber, the surgeon segments the IOL to explant it, and uses one of several techniques to secure a posterior chamber implant to the sclera, 2 to 3 mm posterior to the limbus.

|

|

Pars plana vitrectomy and preparing to deliver the displaced IOL/capsular bag complex. |

The additional benefit becomes even more apparent when glaucoma procedures, corneal transplants or iris reconstruction need to be combined with the lens exchange, thereby reducing the need for multiple separate surgical interventions while keeping the visual outcome to the highest level possible. This is what we’ve defined as middle segment surgery.

Obviously, not all cases can be appropriately performed “all-in-one,” but for those that are amenable to such, the anatomical and visual benefits to the patient are obvious, as well as reducing the burden of several sequential surgical procedures. When we consider the patient’s time off work to recover, reduced earning potential during this time, surgeon and hospital/surgery center fees, and the impact on caretakers (and their own time off work and reduced earning potential) the benefits are compounded.

Advantages and Limitations

While there are several advantages to this approach, we must also recognize its limitations. I strongly believe we can overcome them if we come together as one ophthalmology community.

The first advantage of working in the pars plana is being in a closed system: There are usually two to four sclerotomy incisions 1 mm or less wide, and when the surgeon removes the instruments, the system remains closed or can be closed with plugs.

Next, a pars plana approach is advantageous for controlling fluid mechanics. When one places an infusion line through one of the sclerotomies, this maintains the eye under controlled pressure. We have a saying: The eye doesn’t like hypotony. Retina, cornea and glaucoma specialists all subscribe to this. A soft eye is the source of many problems. So, if we’re able to control fluid mechanics when injecting/irrigating fluid into the eye without fluid egress elsewhere, this is advantageous.

Historically, anterior segment surgeons often had advanced knowledge of replacement implant choices, location and fixation techniques. In the past, vitreoretinal surgeons had a tendency towards placing implants in the anterior chamber—this introduced additional risks of corneal decompensation, uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema syndrome, chronic cystoid macula edema and glaucoma, threatening the future stability and function of the eye. Many anterior segment surgeons, especially cornea specialists, have long advocated against the placement of such lenses, likely to the extent that most modern day anterior segment surgeons have eliminated the anterior chamber IOL entirely from their arsenal. There has also been incremental movement in change of practice among retinal colleagues as the years have gone by. At least here at Wills, the retina service started sclerally fixating implants about a half dozen years ago. They’ve made huge strides in becoming well-versed in IOL options, biometry and fixation techniques. They generally remain less focused, however, on the visual than structural outcomes, which frankly is the nature of the sub-specialty.

This isn’t to say that we can’t meet in the middle (hint, hint). In fact, quite the opposite, there are limitations on both sides, which we firmly believe can be resolved with formal training. There is so much to be learned from each other.

A core limitation exists among anterior segment surgeons: they’ll often not have formal training in pars plana vitrectomy, placement of trocars, placing posterior infusion/irrigation lines or experience doing high-speed vitrectomies (most surgeons are using 23-, 25-, or 27-gauge cutters at 1,200, 2,500 or even 6,000 or 8,000 cuts per minute).

There are also specific instruments that an anterior segment surgeon would need to access for successful middle segment surgery, including endoilluminators and posterior viewing systems. Endolasers are also necessary if one identifies a tear in the retina and needs to laser around it to prevent it from developing into a detachment. Of course, this can also be referred promptly to a retinal colleague.

|

|

Sclerally fixating a PCIOL using the Yamane technique. |

The instruments and techniques described above are within the purview of a vitreoretinal surgeon. An anterior segment surgeon isn’t formally trained to use them but certainly can be. The instruments should be available in any OR where a vitreoretinal surgeon operates.

Conversely, vitreoretinal surgeons typically don’t have access to the latest biometry and keratometry devices, which could have downstream impact on refractive outcome for the patient.

Finally, the anterior segment surgeon should cooperate with and have access to a vitreoretinal surgeon in the event there’s a problem requiring the assistance of the VR surgeon to complete the case, or at least the safe closure of the eye and sending the patient to the VR specialist the following day.

Formal Training and Educational Support

Over the past two years, we’ve reached out to department chairs around the country to see whether they would be interested in making middle segment surgery training a reality. To be clear, this wouldn’t be limited only to increasing the surgical repertoire of the anterior segment surgeon. It would also welcome posterior segment surgeons wishing to extend their skills in middle segment reconstruction, IOL choices, biometry and the variety of lens fixation techniques.

What do we need to do to make cross-training happen, followed by appropriate credentialing? Would a person need formal training, and how much? Thirty years ago, in order to get privileges for phacoemulsification, one had to show that one had some experience—10 or 20 cases—and an experienced surgeon would sign off on that. It was much the same with LASIK, ICLs and so on. We believe there must be some formal training. Ultimately, at my institution for example, we aspire to see cornea fellows rotate on the retina service, perhaps a week every three months. They would gain experience with trocar and infusion line placement and using a posterior viewing system. In addition, the cornea and cataract services would invite the retina fellows to rotate and learn about biometry, lens materials and scleral fixation techniques.

This leaves the question of training ophthalmologists who are already in practice. We all subscribe to the idea of knowledge transfer. Many people, like myself and others involved in this, have a desire to educate colleagues on how to do these procedures themselves to the safest levels possible, thereby creating a standard that ultimately results in better patient outcomes. Our plan would entail establishing a few locations around the country to which we would invite surgeons to come to a weekend or two-day course to observe the procedure and see the patients the next day. This is what we did when DSEK was introduced in 2005 and DMEK in 2012.

Last October, we hosted a seminar on middle segment surgery at the American Academy of Ophthalmology meeting in Chicago, and since then have received ongoing words of support from peers and colleagues, both anterior and posterior segment surgeons in academic institutions and private practices alike. We also recognize that there are talented anterior segment surgeons who have already been teaching this skill in their own areas. We know we can combine forces and garner support from department chairs in order to create training in this area of special interest and effect appropriate credentialing.

We truly believe this is the wave of the future. The population is aging and the incidence of displaced IOLs is on the rise. We need more specialists, coming from both anterior and posterior segment surgery backgrounds, interested in middle segment surgery, to handle these cases. This special interest group will be driven mostly by one factor: patient outcomes.

Dr. Hannush is an attending surgeon in the Cornea Service at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia and a professor of ophthalmology at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. He consults for Kowa Company.

Dr. Ifantides is an anterior segment surgeon at Tyson Eye in Cape Coral, Fla., and an adjunct assistant professor of ophthalmology at the University of Colorado. He consults for or receives grant support from Centricity Vision, Spect, Allergan, AcuFocus, Ace Vision Group, Alcon, J&J Vision, Zeiss, BVI, Tarsus and New World Medical.

Dr. Trinh is a cornea, refractive surgery and external diseases staff specialist at Sydney Eye Hospital in Australia. She has no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Oliver is chief of the Retina Service and an associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of Colorado. He has no relevant disclosures.