|

A few months ago, we began our discussion on what I dubbed “dangerous ptosis”—ptosis as an initial manifestation of a potentially significant disease process. Horner syndrome and CN-III dysfunction were discussed in that forum. In this issue of Plastics Pointers, I will present the remaining three entities: myasthenia gravis; conjunctival or orbital processes; and chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia. In addition, the issue of contralateral lid retraction will be mentioned. If you haven’t had a chance to read the previous segment, I urge that you do so in the

March 2012 issue or online before proceeding here.

Myasthenia Gravis

The hallmark of MG is variability. Essentially all patients with ptosis will complain, if prompted, that their ptosis is worse toward the end of the day simply because their frontalis muscles tire out from raising the brows to clear the visual axis. Patients with MG will usually report that their ptosis changes throughout the day and also changes sides. Many patients with myasthenic ptosis will also complain of diplopia unless the ptosis is severe enough to block one visual axis. Questions to ask and document in such patients include:

- Systemic medications?

- Shortness of breath?

- Dysphagia?

- Weakness in the proximal extremities (i.e., difficulty climbing stairs or raising arms over head)?

- History of other autoimmune disease (especially thyroid dysfunction)?

Frequently, patients will not volunteer information regarding muscle weakness, dysphagia or shortness of breath to their ophthalmologist. However, these questions must be asked by the clinican, since it is crucial in any patient who presents with so-called bulbar symptoms (dysphagia or respiratory difficulties) to refer promptly for treatment to avoid a myasthenic crisis.

|

If MG is suspected as the etiology of the ptosis, a variety of tests (with approximate percentage of sensitivity noted) are available:

• Rest test (50 percent).• Edrophonium (Tensilon) test (~75 percent).• Acetylcholine receptor antibodies (45 to 65 percent).• Single fiber EMG of orbicularis oculi (88 to 92 percent).• Ice test (70 to 90 percent sensitive, 100 percent specific).

Chest CT and thyroid function tests should also be obtained in all patients.

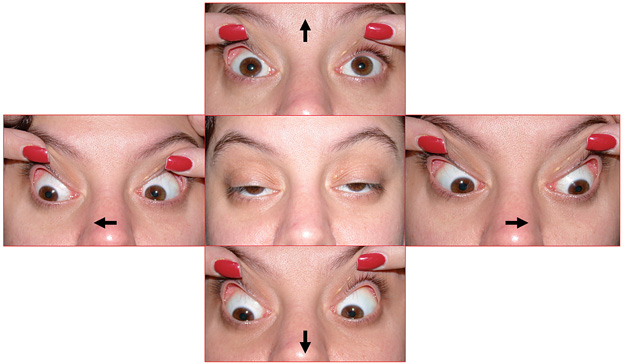

Many patients with myasthenic ptosis also have an external ophthalmoplegia, although a significant number will simply present with isolated ptosis. Even if external ophthalmoplegia and strabismus is present, some patients will not complain of diplopia because their ptosis effectively blocks one visual axis. Patients with myasthenic ptosis will also frequently have orbicularis oculi muscle weakness that may manifest as lagophthalmos.

Testing for MG varies between centers. Some still advocate the use of edrophonium (Tensilon), although such testing must be carried out with adequate resuscitation equipment readily available. Other experts recommend the combination of acetylcholine receptor antibody testing and single-fiber electromyography of the orbicularis oculi or frontalis muscles. Of note, Medicare has recently mandated that only the binding antibody will be reimbursed, since it is the most sensitive for picking up MG; if the clinician is not specific or reflexively orders all three available antibody tests (binding, blocking and modulating), an irate patient with an unpaid laboratory bill may show up on the doorstep.

|

Once MG is diagnosed, the patient should undergo chest imaging to rule out a thymoma or thymic hyperplasia and be referred to a neurologist for further management. Ptosis repair in MG is quite difficult because of variability and is usually deferred until all nonsurgical modalities have been exhausted.

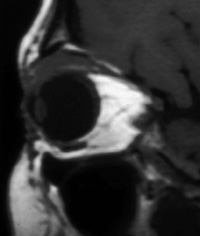

Occult Eyelid or Orbital Masses

All patients with ptosis should undergo careful examination of the conjunctiva and superior cul-de-sac, and the presence or absence of globe malposition (ex/enophthalmos, hyper/hypoglobus) must be documented. Eyelid eversion should also be performed. In younger patients, occult foreign bodies (especially contact lenses) can on occasion erode through the conjunctiva into upper eyelid tissue and present clinically as a droopy lid. In older patients, lymphoma should always be suspected. If a mass is indeed palpated, imaging of the orbit is warranted. If any abnormal-appearing tissue is noted intraoperatively during ptosis repair, it should be sent for histopathologic analysis.

CPEO

Chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia is an umbrella term for a variety of mitochondrial disorders that present with slowly progressive ptosis and external ophthalmoplegia. In contrast to many patients with MG, patients with CPEO rarely complain of diplopia because of the chronic and symmetric nature of their external ophthalmoplegia. In early stages, the diagnosis can be difficult to make clinically. In late stages, the almost frozen globes and severe ptosis present less of a clinical challenge. Differentiation of CPEO from MG may at times prove frustrating, although two findings are highly suggestive of MG: variability and orbicularis oculi weakness. Over time, patients with CPEO also develop atrophy of the facial muscles, resulting in a mask-like facies that is not seen with MG.

Because CPEO is a mitochondrial disease, patients are at risk for life-threatening co-morbidities, most commonly cardiac in nature. The hallmark of CPEO coupled with cardiac disease is Kearns-Sayre syndrome (KSS). Patients with KSS invariably present by the late teens or early twenties and are at significant risk for high-grade cardiac conduction defects, which may result in sudden cardiac death. All patients with suspected KSS (and for that matter, all patients with suspected CPEO) should undergo urgent cardiologic evaluations. In addition, patients with suspected KSS should have a complete retinal examination; the presence of a pigmentary retinopathy (sometimes incorrectly described as “RP-like”) supports the diagnosis. Definitive diagnosis of CPEO typically requires a muscle biopsy for routine histopathology, special staining, and possibly electron microscopy. The goal of ptosis correction is to just clear the visual axis without causing excessive exposure keratopathy.

|

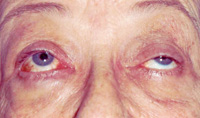

Contralateral Lid Retraction

Patients often notice asymmetry of the eyelids (“The lids just don’t look right”), but may then incorrectly conclude that one side is droopy when, in fact, the contralateral side is abnormal.

The normal upper eyelid typically assumes a position midway between the pupil and the superior limbus. Any upper scleral show is always abnormal. (Remember that lower eyelid scleral show often occurs as a normal finding in patients with shallow orbits). Furthermore, an eyelid position at the superior limbus is probably also abnormal.

|

On occasion, unilateral ptosis can result in contralateral lid retraction due to Hering’s law. This typically requires occlusion or near-occlusion of one visual axis by the ptotic lid and may be seen more frequently if the contralateral eye has poorer vision. Any patient presenting with uni- or bilateral upper lid retraction requires a work-up. The first question to ask is whether the patient has had any trauma or surgery to the eyelid. An overly aggressive cosmetic blepharoplasty may result in lid retraction and lagophthalmos, but very often patients do not volunteer information about cosmetic procedures. Patients should also be queried about other systemic manifestations of thyroid disease, including weight change, heat/cold intolerance, changes in bowel habits, anxiety, heart palpitations, etc. A positive family history of thyroid disease can be found in up to 50 percent of patients with thyroid eye disease (TED).

As noted earlier, all patients with upper lid retraction should undergo eyelid eversion and examination of the superior cul-de-sac. Lid lag on downgaze (von Graefe’s sign if associated with TED; pseudo-von Graefe’s sign for all other causes) should be looked for. Occasionally, aberrant CN-III regeneration or an old facial nerve palsy may present as unilateral lid retraction.

All patients presenting with lid retraction should undergo thyroid function testing. In most cases, a selective (3rd generation) TSH suffices. Some clinicians also obtain a thyroid-stimulating antibody (TSI) level, positing that this may be elevated in euthyroid patients and may prove to be a reliable early marker of subsequent dysfunction. If the TSH and TSI are normal, the patient should be retested every six months for two to three years, or sooner if he becomes systemically symptomatic. Up to 10 percent of patients with clinically obvious TED can be euthyroid on presentation. Of euthyroid patients, 25 percent will develop thyroid function testing abnormalities within one year, and 50 percent will do so within five years.

Ptosis is a common condition and, fortunately, the majority of etiologies are benign. However, a few history and examination points can rule out dangerous causes of ptosis. The simple mantra of “upper lid, pupils, and EOMs–if one is abnormal check the other two” cannot be overemphasized. REVIEW

Dr. Bilyk is an attending surgeon in the Oculoplastic and Orbital Surgery Service at the Wills Eye Institute, and an associate professor of ophthalmology at Jefferson Medical College. Contact him at Neuro-Ophthalmologic Associates (215) 825-4796.