Femtosecond laser cataract surgery has become one of the most controversial technologies to come along in years. The reason for the controversy is no mystery: The new systems cost about a half million dollars, and it’s not yet clear that the benefits are worth the investment.

Although the technology is still in the early adopter phase, a number of surgeons have now been using these systems for as long as two years, and nothing makes the value of something as clear as real-world, hands-on experience. Here, six surgeons share their reasons for taking the plunge, their experiences using the technology and their current thoughts on whether the investment was worthwhile.

Deciding to Buy

Two factors seem to make surgeons receptive to becoming early adopters of this technology: an ongoing interest in offering advanced options to patients, (usually including premium IOLs), and previous experience with femtosecond technology.

Barbara Bowers, MD, owner and medical director at Barbara Bowers MD PLLC & Paducah LASIK Center in Paducah, Ky., and assistant professor of ophthalmology at the University of Louisville, has been successful at converting appropriate patients to premium IOLs, so when femtosecond cataract technology came out, she was interested. “I read everything written about it,” she says. “I thought, ‘I’m a pretty good surgeon; I don’t know that this will make me that much better.’ On the other hand, I realized that it might be valuable to make perfectly round, perfectly sized capsulorhexes. Perhaps more important, the ability to do LRIs with great precision with the help of OCT was a selling point. I have patients who want multifocals but have so much astigmatism that I don’t feel I can correct it manually. With this laser, I can. That was what really got me interested.”

Dr. Bowers says she was very comfortable with the new system from the start. “I’ve used a number of femtosecond lasers, and the one we purchased for cataract is the easiest one I’ve ever used,” she says. “On the other hand, somebody who has never made a LASIK flap with a laser—who has never put an interface down on a patient’s eye and turned the suction on and worried about how long the suction will be on, how high the pressure is and whether the patient is comfortable—that surgeon could be uncomfortable for the first few cases. It’s a completely different situation from a standard cataract procedure.”

Some surgeons jumped in almost as soon as the technology became available. “Our surgical center purchased the third unit in the United States, and we’ve had it for almost two years now,” says Eric Donnenfeld, MD, clinical professor of ophthalmology at New York University Medical Center and a partner at Ophthalmic Consultants of Long Island. “We accepted the challenge of using the technology early on, knowing that it would certainly improve over time. As it turned out, the laser has been a very pleasant part of our practice.

“What’s been most impressive for me is the improvement in the hardware and software over the past two years,” he explains. “We’re on our fourth software upgrade and our third hardware change. Two years ago the laser procedure took two and a half minutes; now it takes about 40 seconds.”

A more recent convert is James J. Salz, MD, clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of Southern California, Keck Medical School, and in private practice in west Los Angeles. Dr. Salz only recently began using his femtosecond laser cataract system, and has done fewer than two dozen eyes. “I was comfortable from the outset because I’ve used a femtosecond laser to make LASIK flaps for years,” he explains. “Using the laser to make the rhexis and prechop and soften the nucleus is included when we correct astigmatism, so I’ve done that in every case. However, I usually don’t use the laser to make the side port incisions or the main cataract incision because so far it doesn’t place those incisions exactly where I want them. So, I do those by hand.” He notes he has not had any surgical complications so far, although he attributes that, at least in part, to careful patient selection.

Dr. Salz says he believes the laser has added value for the patient as well as for himself. “It definitely does a better, more consistent rhexis than I can achieve,” he says. “It also makes better, reproducible arcuate incisions at the proper depth because of real-time pachymetry over the exact area where you’re placing them. I’m now more comfortable recommending arcuates for correcting low to moderate astigmatism, and patients are more receptive to the idea of correcting astigmatism with the laser than with a blade. The pre-chopping also allows the surgeon to use less phaco energy to emulsify the nucleus.”

Proceeding With Caution

Some more skeptical surgeons only became interested after seeing others’ early successes and failures. “When the concept of femtosecond laser cataract surgery was first brought up to our surgery center board, I was against it, primarily because of the cost,” notes Henry D. Perry, MD, senior founding partner at Ophthalmic Consultants of Long Island and chief of the corneal service at Nassau University Medical Center. “However, my partner was very much in favor of it and felt that it was something we should try, so I eventually agreed.”

After noting early complications experienced by others in his practice (which dropped off dramatically over time) Dr. Perry proceeded to adopt the new technology cautiously. “It did sound really good for doing relaxing incisions after corneal transplantation, so I started doing that,” he explains. “I did about 25 cases, making me more familiar with the technology. I saw that the OCT really provided a tremendous advantage in terms of the depth of the incision and precision of placement.

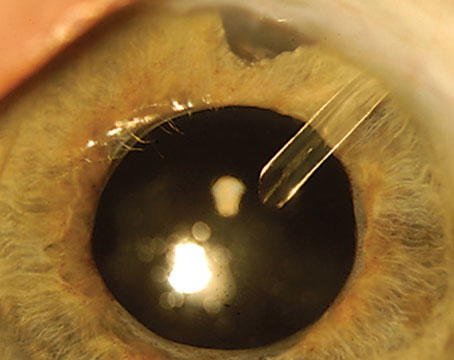

“Then I decided to do a capsulotomy,” he continues. “But when I was ready to do my first one, my fellow said, ‘Oh, go ahead and do the whole procedure.’ So I did the whole case, and I found it to be easier than a manual procedure. The capsulotomy is always the most challenging part; you’re afraid of somebody moving or coughing. It was very nice to have that done by the laser.”

Dr. Perry says after that experience he began performing laser cataract surgery regularly. “Eighty to 90 percent of the time there were still some tags left when making the capsulotomy, so I had to use the capsulorhexis forceps to finish the capsulotomy,” he says. “But since I always check for tags, we have not had any of them lead to tears or spread equatorially. I didn’t have any posterior capsule tears in my first 100 cases.

“With experience I started to notice that after the laser I could break up the nuclei of a soft cataract with almost no ultrasound,” he continues. “In more firm cataracts we still had to use ultrasound, but the laser was very helpful in terms of divide and conquer, which is a technique I’ve always favored.”

Ultimately, Dr. Perry says using the laser for cataract surgery has become his procedure of choice. “I explain to my patients that it’s in their best interests to have a machine do the capsulorhexis rather than have me do it by hand,” he says. “At this point, I think more than 50 percent of my cataracts are done with the femtosecond laser.”

Another gradual convert was Jonathan Stein, MD, clinical assistant professor at NYU School of Medicine and a cataract and refractive surgery specialist in Fairfield, Conn. Dr. Stein explains that as a fellow he had trained with Dr. Donnenfeld; several years after taking over his own practice in Connecticut, he was invited to come to Dr. Donnenfeld’s practice on Long Island to try using the new femtosecond laser.

“I did my first cases in April or May of 2011,” he says. “I did about 10 cases a month for a year or so. Eventually, we made the decision to purchase a femtosecond unit for my surgery center in Norwalk. So far, it’s been a great addition to our practice. There’s something about lasers that scares a small percentage of patients, but the vast majority of them think it sounds like a great technology.”

Uday Devgan, MD, chief of ophthalmology at Olive View UCLA Medical Center, associate clinical professor at the UCLA School of Medicine, and in private practice at Devgan Eye Surgery in Los Angeles, was another cautious convert. He has worked with his femtosecond system for about a year and a half.

Dr. Devgan agrees that a surgeon’s background can be a significant factor in determining how readily he’s likely to embrace this technology. “Some surgeons, like me, are actually very conservative,” he says. “I’m cautious partly because I don’t necessarily want patients to be part of my learning curve unless I think there’s a benefit for them. So I’ve been very slow to uptake this in my own practice.

“Meanwhile, other surgeons in our center are jumping right into the deep end and doing the majority of their cases on it,” he says. “I think the surgeons who use it the most in our center are the ones who are primarily LASIK surgeons who have gone back and implemented phaco since the LASIK market tanked in 2008. They find it natural, because if you’ve used the femtosecond laser for LASIK, you understand the concept of patient docking, the formation of gas bubbles and so forth.”

Have Outcomes Improved?

One of the central issues in the debate regarding the value of the new technology is whether it’s improving outcomes. After using the laser on a limited basis for a year and a half, Dr. Devgan says he’s not convinced the refractive accuracy of his outcomes is greater. “A lot of things contribute to your lens calculation, including your corneal measurement, the axial length, the formula you use and the effective lens position,” he says. “I think the formulas are probably the biggest source of error. The rhexis is just one small part of the equation.

“When I look at these eyes, the rhexis is prettier; it looks nice and it overlaps great,” he notes. “And it makes some sense that a perfectly round, symmetrical cut would help the lens stay in position better; it would tend to shrink-wrap evenly when the capsule contracts after a couple of weeks. The question is, if I compare a manual rhexis that’s about 5 mm and a laser one that’s exactly 5 mm, is there really a difference in the refractive outcome for the eye?

“Some studies suggest that maybe there is, but in my own hands, I haven’t appreciated a striking difference,” he concludes. “I’d really like to see convincing data with a large margin of difference before I draw any conclusions.”

There seems to be broad agreement that the laser adds accuracy and an expanded treatment range to the process of correcting astigmatism with incisions. However, Dr. Bowers notes that making LRIs with the laser is not the same as making them manually. “What percentage depth should I go? What arcuate length? What optical zone? At the outset you’ll have a few cases that are under- or overcorrected,” she says. “On the other hand, it only took me about 10 patients to figure out what my nomogram was. Now I find I can treat a lot more astigmatism than I felt comfortable treating manually, and that has allowed me to put multifocal lenses in people with up to 2 D of astigmatism. My cutoff used to be 1.25 D. I think that has enhanced my practice a lot.”

Dr. Stein agrees. “I don’t have any proof that I’m getting better outcomes because I haven’t done an official study,” he says. “But you can correct larger amounts of astigmatism with the laser. And if you have a toric lens, combining that with the laser allows you to make the astigmatism correction very precise. Although doing the capsulotomy is a little different from doing one manually, it’s a perfect circle, the exact size you want and centered where you want it to be. A skilled surgeon can come close to that, but there will always be times when something goes awry.”

Despite her initial skepticism, Dr. Bowers now believes the laser is also changing the effective lens position. “Just as surgeons have their own A-constant for lens implants, I think every surgeon will have a nomogram for these lasers,” she says. “Over the past nine months I’ve found that I need to rework my surgeon factors and my lens A-constants a little bit because my results are coming out a little bit more hyperopic than they did when I wasn’t using the femtosecond laser system. So I do think it has an effect on postop refractive outcomes.”

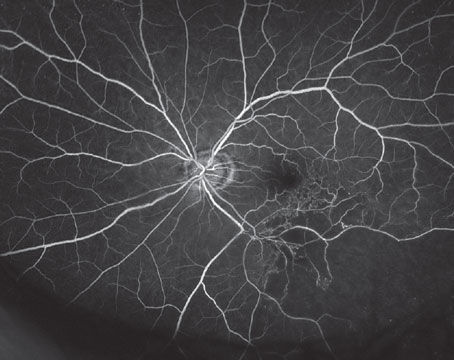

Other surgeons (both with and without financial connections to the manufacturer) feel their overall outcomes have improved. “There’s no doubt in my mind that I’m getting better phacoemulsification and better refractive outcomes,” says Dr. Donnenfeld. “I’m putting less energy into the eye and having fewer complications. My patients are seeing better and faster, and they’re very appreciative of the outcomes that we’re able to achieve.” He notes that astigmatism control has been a key to their success, and adds that they’ve begun tracking their data to see exactly how much outcomes are improving. “In the meantime, some improvements are easy to see, such as changes in our rate of vitreous loss,” he notes. “We’ve had zero vitreous loss in our last 150 cases, which is obviously a nice result.

“Early on I was battling my emotions,” he adds. “I was looking at this and thinking, ‘Is this really better? Does it really make a difference?’ Now I don’t have any hesitation about saying that it’s clearly better in many different parameters.”

“I’ve noticed that my cataract patients have better vision on postop day one,” says Dr. Perry. “I see less edema. On the downside, I notice that I do have more conjunctival hemorrhage because of the suction device. However, I think the manufacturer is developing new devices that produce less suction, so that problem may decrease in the future. Overall, my patients’ vision has been better. More important, my operative complication rate, which was low, is now even lower. It was about 1 percent; now it’s less than 1 percent.”

Surgical Complications

Early reports in the literature indicated that some surgeons ran into complications after switching to laser cataract surgery. “Michael Lawless’s group in Australia has published multiple studies regarding complications with femtosecond cataract surgery,” notes Dr. Devgan.1-3 “The first study summarized their early experience with the laser, covering their first 200 cases. Two out of their first 50 eyes had a dropped nucleus, which normally is a rare complication—I’d say less than 1 percent with standard cataract surgery. Two out of 50, which is 4 percent, is shocking. But the next study they published reported their complication rate during their next 1,300 cases. The dropped nucleus rate was zero, and other complications dropped by a factor of 10—far more acceptable.

“Similarly,” he continues, “in their first 200 eyes, they made 1.5 docking attempts per surgery; in other words, every other eye had to be docked twice. For the next 1,300 eyes, their docking rate was 1.05, meaning only one in 20 eyes had to be redocked. So docking errors dropped from 50 percent to 5 percent. That had nothing to do with the laser, but with the surgeon figuring out how to do it. Femtosecond lasers are just like any other tool—there’s a learning curve.”

Dr. Devgan says the only surgical problems he has personally encountered were a loss of suction and an incomplete rhexis. “The partial rhexis was no big deal,” he says. “I just took the forceps and finished the other half. The patient did fine. But other, more severe complications have been reported: broken capsules, dislocated lenses, poorly placed incisions. Surgeons who do more femtosecond cataract surgeries are more likely to have complications, and there have been a few of these at our center.

“In any case, I don’t think these complications are the fault of the laser; I think it’s the way we program and dock the laser,” he adds. “The laser just does what we tell it to do.”

Better With Experience

Having complications at the outset seems to be a common experience. “Out of the first 20 cases in our surgery center there were two dropped nuclei, both in cases done by excellent surgeons, and four cases of vitreous loss,” notes Dr. Perry. “Being the person in charge of quality control at our surgery center, I was perplexed. However, I was assured that there was a problem with the software and that it would be taken care of. The software was soon upgraded, and a few months later I spoke with our fellow, who operates the laser in our surgery suite. He said the complication rate was down and the machine was working well.”

Dr. Stein also reports having problems at first, but says modifications are resolving them. “For example, we’ve modified the way we do the treatment so that if bubbles occur, they pop right out into the anterior chamber and you remove them when you first go into the eye,” he says. “Seeing the edges of the capsulorhexis is now very easy, and we frequently have completely free caps before we even get inside the eye. The tags and radial tears that did occur at the beginning are now very infrequent. The same is true of incomplete treatments, which have probably been minimized in part because of the reduced time now required for the procedure. Originally it took four minutes and 40 seconds of continuous suction; you’re bound to have fewer suction-related problems when it only takes 40 seconds.”

Dr. Devgan notes that complications are being reduced by improvements in the software and hardware. “During the year and a half we’ve had our machine the company has been very good about updating software and coming out with new upgrades,” he says. “Alcon is even providing a new, softer docking interface for the patient that uses less pressure, so it’s gentler on the eye and produces no corneal suppression.”

“Our initial problems have become much less common as the software and hardware has improved,” agrees Dr. Donnenfeld. “When we first had the machine we had no free-floating capsulotomies; last year we had about 40 percent; now we’re up to well over 90 percent. Those types of improvements, which are logarithmic, are pushing the technology forward. The machine is much better today than it was a year ago.”

In any case, not every surgeon has experienced complications. “After nine months, I haven’t had any issues with complications,” says Dr. Bowers. “I read the literature and all the pearls about how to avoid complications from posterior gas bubbles and aggressive hydrodissection before I ever did my first case. I’ve never had any issues like that, or radial tears. I haven’t had any problems with incomplete capsulotomies, or tags. I find that I can just go in and lift the capsule fragment off. And I’ve never had any trouble seeing the edge of the capsulotomy, although I got a new microscope three or four months before I purchased the femtosecond laser, which may have made a difference.

“I know that being complication-free isn’t the experience of most people, based on what I hear,” she adds. “I don’t know if it’s the laser or my settings. I don’t think it’s anything special that I’m doing. But I personally have not had any issues with those complications.”

Is It Paying Off?

Given the size of the investment, being able to make back the financial outlay is at the top of the list of most surgeons’ concerns. “I believe the financial issues surrounding owning one of these lasers are the only rate-limiting factor for most people,” says Dr. Donnenfeld. “It’s not whether the technology is better; it’s whether they can afford to put it into their clinic or hospital.”

So far, the surgeons interviewed for this article say the investment is paying off. Some attribute that to having a large, multi-surgeon practice—but it appears to be working out in some small practices, too. “If you can do 400 cases a year with the laser, it pays for itself,” says Dr. Donnenfeld. “That was the model we used, and we’re way over that number now. Not only are we getting better results, but it’s making a profit for the surgery center as well. We offer it to patients as a premium product and they share in the expense. We do that even when we use it for astigmatism, which is reimbursable.” Dr. Salz also says that the laser is paying for itself, which he attributes to having a large number of high-volume surgeons at his surgery center, many of whom use the laser a lot.

Drs. Stein and Perry also report positive financial results. “You’d be surprised who is willing to pay for this,” notes Dr. Stein. “I offer it to everybody. If the patient says, ‘That’s a lot of money,’ I say, ‘How much have you spent on your teeth? This is your vision; wouldn’t you want the best possible visual outcome?’ Of course, I practice in a relatively affluent area. I’m sure fewer patients would be willing to pay for it in an inner city population. But some patients just want to hear that a laser is taking care of them. They know that laser cataract surgery is out there.”

Dr. Perry’s practice is also located in an affluent part of the country, but he doesn’t believe patient demographics are the deciding factor in whether patients are willing to pay for the technology. “If somebody’s going to have cataract surgery on their eye, and you have a procedure that’s safer, I think most patients will try to come up with the money to pay for it,” he says. “I also try to have a sliding scale; if I know that the patient is indigent, I just ask him to pay the laser fee.”

Perhaps more remarkable, Dr. Bowers, who runs a solo practice in the Midwest and is the only surgeon using her laser, also believes the investment is paying for itself. “I think it was a good move financially,” she says. “My attitude toward technology is: If I think it’s going to enhance patient outcomes, and it’s going to make my life easier, and it’s going to make my patients happier—which in turn makes me happier because I’m not dealing with unhappy patients postop—I don’t care if I make money, I just want to break even.

“That was my attitude when I built a LASIK suite onto my office,” she continues. “That turned out to be a good choice; I more than broke even. At this point I believe we’re also doing better than breaking even with femtosecond cataract—I think we’re doing extremely well.”

“It’s all in the kind of practice you have,” she adds. “I found it very easy to add to my practice because I was already comfortable discussing premium IOLs with patients. I basically just took an extra 30 seconds to mention the possibility of doing the surgery without blades. On the other hand, if you have a one- or two-person practice that does not do a lot of multifocals or torics, and you’re not comfortable taking chair time to talk to patients about upgrades and added expense, it might be a different story.”

Making the Best of It

Based on their experience, surgeons offer these suggestions to those who may be adding this technology to their practice:

• Do your homework before buying one. “I’ve been happy with the system from the beginning, but I think that’s because I did my homework,” says Dr. Bowers. “You need to figure out how the flow will work, how you want to promote it, how you’re going to incorporate it into the OR, how you’re going to incorporate it into your surgery day—all before you purchase the machine. Don’t try to figure it out after you’ve got patients scheduled. And get your staff educated and onboard before the instrument arrives.”

Dr. Donnenfeld agrees. “There’s no reason for anyone to start laser cataract surgery without first looking at the evolution of the technology,” he says. “Today, newcomers should be able to avoid the pitfalls that made this surgery less efficacious a few years ago.”

• Don’t worry too much about the extra time required. “We have our laser system inside the OR, which is big enough to allow that,” says Dr. Stein. “Essentially, after a case is complete, we use the time required to set up for the next patient to prep the patient and do the laser procedure. If you do this very efficiently, you can still be ahead of the nurse team that’s readying the equipment.”

Dr. Bowers says that, in any case, the small amount of additional time required to use the femtosecond laser system in her solo practice has diminished over time, and has been more than offset by the financial compensation. “It did cause a little bit of slowdown for the first few weeks,” she says, “but literally after the first three or four weeks, we had it down.”

• If possible, have someone else do the laser portion. “If you don’t have someone else doing this procedure while you’re doing the rest of the surgery, the technology will just increase the cost of the surgery and use up operating room time,” says Dr. Perry. “A designated laser person can probably do six to eight lasers an hour and really keep the surgery center hopping.”

Dr. Donnenfeld concurs. “In our practice, our fellow does most of the laser parts, which speeds me up about 20 percent,” he says. “If you have to do your own laser in addition to the phaco, I’d guess it would slow you down about 20 percent.”

• Put the laser in a room separate from the OR. “I studied this before purchasing the instrument and decided that having an extra room for the laser was the best way to go,” says Dr. Bowers. “I spoke to many surgeons and weighed the pros and cons. Many of the surgeons I spoke to who managed to fit the machine into their ORs said they’re now looking for a way to move it out into a separate room, just to make the flow better.”

• If possible, use three rooms to maximize flow. Dr. Perry says that having three rooms available for surgery makes a big difference. “If you have two rooms, it slows you down,” he says. “We have three surgical rooms, with the laser in one. You can alternate using the other two rooms for the non-laser part of the surgery. While you perform phacoemulsification in one room, the next patient has been treated with the femtosecond laser and is moved into the other room. When you switch to that room, the first room is prepped for the next surgery while the next patient is treated with the laser, and so forth. This arrangement can be very efficient.”

• Schedule all your right eyes and left eyes together on different days. Dr. Bowers says this scheduling strategy has enabled her to avoid using any additional time beyond the time she’s actually sitting at the laser performing the procedure, which is about two minutes. “I’ve only added one staff member, who actually runs the laser,” she says. “She gets the patients in the room, gets them marked, gets them ready. I sit down, put the patient interface on, do the treatment, and leave and go straight to the OR. There’s no need for a ‘quarterback’ to point me in the right direction regarding which room to go to. When I’m only doing right or left eyes, I know which room to go to. The flow is phenomenal.”

What if you only have two or three laser cases to do? “Do those two or three left eyes one day, then next week do your two or three right eyes,” she says. “I alternate a traditional case with a laser case until I’m done with all of the laser cases; then I go back to doing all traditional cases.”

• Consider advertising it. Although most surgeons say they are not advertising the fact that they offer this option, those who have tried it report that it seems to pay off. “Some of my patients do ask for it when they come in,” says Dr. Bowers. “I’m in a smaller community, and we have done a little advertising. The small amount of advertising we’ve done has been well worth it.”

• Beware of patient choice overload. “If you do offer all of these high-tech options, you have to try not to overload the patient with information,” Dr. Stein points out. “You have to give a clear-cut message as to what you want to accomplish with the patient’s visual outcome.”

Should You Make the Leap?

Surgeons who have made the investment seem positive about their decision—but they’re also sympathetic to those who would rather watch and wait before deciding. Dr. Salz believes that it’s important to at least try it for yourself. “Get access to one if you can,” he says. “I think you will be impressed.”

“I know for a fact that solo practitioners can make a success of this, if they approach it the right way,” says Dr. Bowers. “It is a large investment. But if you think about it, cataract surgery is our number one procedure. We do a lot more of those than we do LASIK. So far, it’s been a very good decision for me and my practice.”

“This technology is proven and improving, and it’s going to create a more safe and secure environment for the patient,” says Dr. Stein. “Whether it’s fully gotten there yet, in comparison to an extremely competent cataract surgeon, I’m not sure. But it’s important to stay current and offer your patients technology that can give them the best outcome, as long as it’s proven and safe. You don’t want to be the guy who is still doing planned extracaps 15 years after phaco is considered the standard of care.”

Dr. Donnenfeld notes that the number of surgeons trying the technology is increasing. “In our practice, some of the most conservative surgeons are now embracing the femtosecond laser,” he says. “Some doctors who never did LASIK or PRK are doing almost 50 percent of their cataract cases with it. These are people who never thought about performing refractive cataract surgery before. They were uncomfortable with manual LRIs, didn’t do excimer photoablation and didn’t think they had the technological expertise to start doing toric,

multifocal or accommodating lenses.

“Now, because they’re getting more reproducible refractive outcomes, they’re more comfortable using those new technologies,” he continues. “So the laser has opened these technologies up to a whole new group of ophthalmologists. Before this, I think only 10 or 15 percent of ophthalmologists offered refractive cataract surgery. Now that we have digital technology that gives everyone the same precision, I think the number of people interested in offering refractive cataract surgery is going to rise exponentially.”

Given that the technology is rapidly improving, why not wait to get involved? “As with anything, technology gets better with time,” notes Dr. Donnenfeld. “The car you buy today won’t be as good as the car you could buy two years from now, but that doesn’t mean the car of today isn’t good. I firmly believe that laser cataract surgery was better than conventional phacoemulsification from the outset, and now that difference is growing.

“Some people want the technology to be perfected before they jump into it, and I have no problem with that attitude,” he adds. “Phacoemulsification is a very good procedure, and there’s no reason to move on quickly if you’re comfortable. In my case, I enjoy developing new technology, as long as I think it’s safe for the patient. And I’m glad I made the switch.”

Dr. Devgan agrees that you can make an argument for waiting to purchase while the technology continues to improve. “That’s a valid point,” he says. “But you can always say, ‘I’m not going to buy one yet because they’re going to come out with a new model next year.’ The companies are smart enough to make it easy and cost-efficient to do the upgrades when they come out. So if you do buy sooner rather than later you won’t be caught with last year’s model.”

“Ultimately, I think it’s still too early to know whether switching to femtosecond laser cataract surgery really makes sense for most practices,” he adds. “In our surgery center the investment made sense, and it still makes sense. But people have to do their own math and decide for themselves.”

Dr. Donnenfeld consults with Alcon, Bausch + Lomb, AMO and LenSx. Dr. Devgan is a speaker for Alcon and a consultant for Bausch + Lomb. Drs. Stein, Bowers, Salz and Perry have no financial ties to any of the technology discussed in the article.

1. Roberts TV, Sutton G, Lawless MA, Jindal-Bali S, Hodge C. Capsular block syndrome associated with femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg 2011;37:11:2068-70.

2. Bali SJ, Hodge C, Lawless M, Roberts TV, Sutton G. Early experience with the femtosecond laser for cataract surgery. Ophthalmology 2012;119:5:891-9.

3. Roberts TV, Lawless M, Bali SJ, Hodge C, Sutton G. Surgical outcomes and safety of femtosecond laser cataract surgery: a prospective study of 1500 consecutive cases. Ophthalmology 2013;120:2:227-33.