As difficult as it may seem, performing cataract surgery on patients with uveitic glaucoma has become more manageable in recent years. Surgeons who rely on the latest approaches to these eyes are using better control of inflammation and intraocular pressure, as well as modern surgical techniques, to achieve outcomes once thought to be elusive.

This how-to update reviews current anti-inflammatory therapies, methods for controlling uveitis, the management of concurrent glaucoma, surgical principles, how to co-manage cases and how to provide successful postop care.

New Treatments

Surgeons believe that a wider range of steroid delivery options in and around the eye, as well as other immunosuppressive and immunomodulatory therapies, have increased the potential for success in these patients. They note that outcomes have also greatly improved because of increased awareness of the importance of controlling inflammation aggressively.

|

|

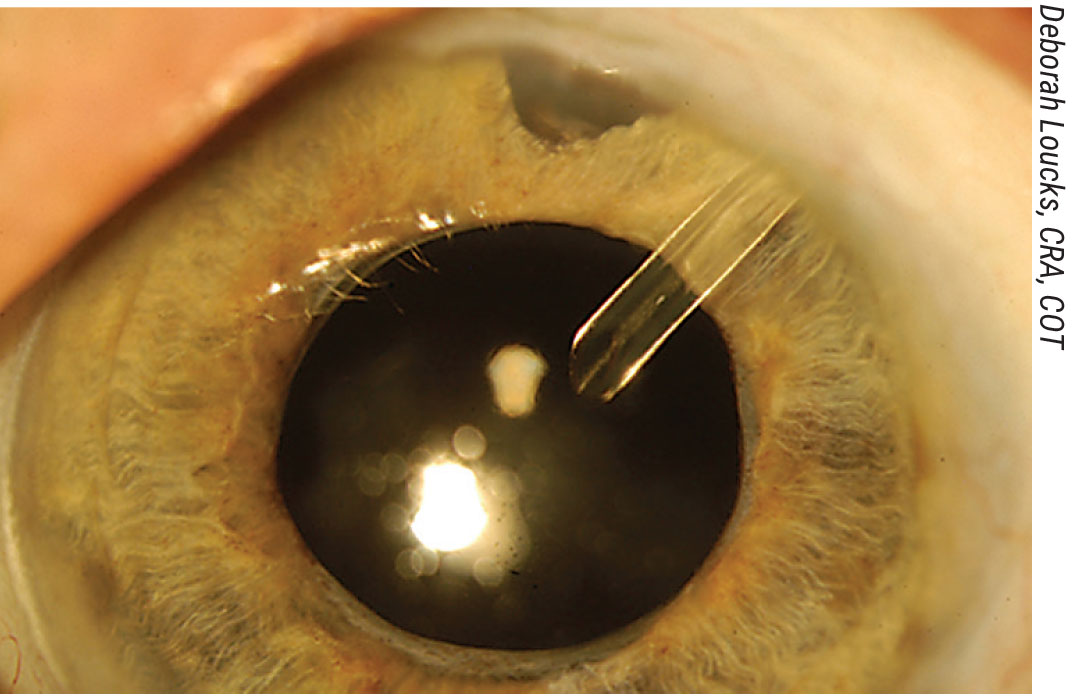

Figure 1. The postop view of a uveitic glaucoma patient who has undergone a phacoemulsification procedure combined with an Ahmed valve placement, corneal patch graft and sub-Tenon’s Kenalog treatment. Click image to enlarge. |

“The many therapeutic options available to us start with topical steroids like Pred Forte and Durezol. Treatments may escalate to sub-Tenon’s administration of betamethasone (Celestone) and triamcinolone (Kenalog), followed by systemic steroid treatments, such as oral dexamethesone or prednisone,” says Mark A. Werner, MD, a glaucoma specialist and cataract surgeon from Delray Beach, Florida. “Alternative immunosuppressant therapies include conventional treatments, such as the generics methotrexate and cyclophosphamide, as well as azathioprine (Azasan, Salix; Imuran, Prometheus). Appropriate biologic immunosuppressant therapies, for which I involve the co-managing support of a rheumatologist or uveitis specialist, include the tumor necrosis factor blockers, such as infliximab (Remicade, Janssen) and adalimumab (Humira, Abbvie).” (See sidebar “Using New Treatments Judiciously.")

Sanjay J. Kedhar, MD, professor of ophthalmology at the University of California, Irvine, and director of the ocular immunology and uveitis service at the affiliated Gavin Herbert Eye Institute, emphasizes the use of the newer biologics to control inflammation most effectively and reduce uveitis-related complications during cataract surgery. “Although the older medications are good, I prioritize the use of agents such as adalimumab and infliximab,” he says.

Before formulating a treatment plan, anterior segment surgeon Eric Donnenfeld, MD, of OCLI Vision, at Island Eye Surgicenter in Westbury, New York, consults with other ophthalmologists and specialists to confirm the diagnosis of each case of uveitis, a complex and multi-faceted disease categorized according to its primary location in the eye and associated with more than 15 inflammatory conditions throughout the body. “I want to see a patient get an inflammatory workup, which could include consideration of infectious diseases, collagen vascular diseases and idiopathic diseases, such as Fuchs’ heterochromic iridocyclitis. (See Differentiating Findings in Uveitis below.) In most cases of uvetitis, we don’t get a diagnosis because the condition is idiopathic. But if we can get a correct diagnosis, we can help patients with more focused therapy to eliminate inflammation, rather than using broad-spectrum therapy.”

Keeping Uveitis Quiet

Differentiating Findings in Uveitis Doctors have recognized for years that uveitis isn’t a single entity, and so managment requires multiple approaches to diagnosis and care. Here, Mark Werner, MD, a glaucoma specialist and cataract surgeon from Delray Beach, Florida, shares some examples of remarkable uveitis entities, with regards to cataract surgery. Fuchs’ heterochromic iridocyclitis is usually associated with a good outcome. The Amsler-Verrey sign is the occurence of a filiform hemorrhage associated with fragile iris vessels after paracentesis at the outset of surgery. The issue can be easily resolved with viscoelastic tamponade. Intermediate uveitis (pars planitis) is associated with more posterior involvement, so it’s less likely to affect the anterior segment or cause posterior synechie. However, it’s associated more frequently with cystoid macular edema. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada, sarcoidosis, Behçet’s and sympathetic ophthalmia are more often linked to severe posterior segment disease and may limit the visual prognosis. Counsel your patients accordingly. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis should be treated with aggressive suppression of inflammation. Glaucoma, hypotony and cyclitic membranes are all potential issues. Rheumatoid arthritis can (as observed anecdotally by Dr. Werner) be associated with poor encapsulation of drainage implants. Securing the plate well with non-absorbable sutures may be advisable when inserting a shunt. — SM |

Dr. Werner says the most important action to take in these cases is to wait. “I hold off on doing cataract surgery until at least three months after I’ve brought the patient’s inflammation completely under control,” he says. “There’s now evidence in the literature to support this classic teaching.1 For Behçet’s disease, the recommended waiting time is six months.”

When managing these patients with steroids, Dr. Werner recommends extra vigilance in monitoring for increased IOP, mindful that you might need to de-emphasize steroid therapy in favor of the conventional and biologic immunosuppressant therapies, requiring you to co-manage treatment with a uveitis specialist or rheumatologist.

“The patients who need these nonsteroidal treatments typically haven’t achieved good control of inflammation, despite aggressive steroid therapy,” he says. “Or they’ve experienced side effects from the steroids. This group may include patients with difficult-to-control anterior uveitis or posterior uveitis.”

Dr. Donnenfeld seeks to quiet inflammation with Durezol. “I usually go with four to six treatments per day, with a tapering dose,” he says. “This is the equivalent of using prednisolone acetate 15 or 20 times a day.”

When necessary, he switches to the other steroids mentioned above and, in the presence of posterior chamber inflammation, may resort to preoperative use of the intravitreal implants, 0.7 mg of dexamethasone (Ozurdex) and 0.18 mg of fluocinolone acetonide (Yutiq). “When these treatments are needed, I’ll seek the assistance of my retinal colleagues,” he says. “Then, when the patient is ready for surgery, I’ll perform a fastidious, meticulous, atraumatic procedure which I think is very important to minimize postoperative inflammation. I also use aggressive postop inflammatory control after surgery.”

Dr. Donnenfeld says nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, blocking COX-1 and COX-2, the cyclooxygenase enzymes associated with tissue damage, play a role in the perioperative period, but not in the long-term management of inflammation. “I use them a week before surgery on patients with uveitis,” he says, “as I want to eliminate any pre-existing prostaglandins that may contribute to postoperative inflammation. Postoperatively, my normal course of nonsteroidals is four weeks. When the patient needs to go out up to three months, I like using the new potent nonsteroidals, such as bromfenac (Bromday, Bausch + Lomb) and nepafenac (Ilevro, Alcon).”

In severe cases of uveitis, Lama A. Al-Aswad, MD, MPH, professor of ophthalmology and population health at NYU Langone Eye Center in New York City, says she treats her patients with “the big guns.” That means preoperative use of a steroid implant, immunosuppressant therapy (provided by a co-managing uveitis specialist) and prednisone. During cataract surgery, she says, she’ll infuse intravenous steroids in the operating room, which she administers to all uveitis patients in the OR, except those with out-of-control diabetes. “After surgery, I continue with immunosuppressant therapy and continue to hit them with both steroids and NSAIDs,” she says. The patient will also most likely have uvetic glaucoma by then, so we’d need to manage the glaucoma as well. Our exact approach depends on the situation, of course.”

Glaucoma’s Ever-present Threat

|

|

Figure 2. Patients with uveitis and glaucoma may have extremely small pupils and shallow anterior chambers. In the case shown above, a pars plana vitrectomy is needed to create anterior space to allow for removal of this patient’s Morgagnian cataract. Click image to enlarge. |

While managing the complicated components of these cases, Dr. Kedhar cautions against overlooking the threat of glaucoma. “We must always keep in mind possible responses to steroid therapy,” he says. “In patients who have more advanced glaucoma or more severe responses to steroids, we may need to consider earlier introduction of the steroid-sparing therapies, such as Humira, Remicade and methotrexate. These treatments help control inflammation and avoid possible pressure spikes that can occur from the use of increased steroid treatment after surgery.”

He also watches for the need for glaucoma surgery. “Many of these patients may need this surgery at some point,” he notes. “It may make sense to do glaucoma surgery to help control the pressure before even performing the cataract surgery,” he says.

At the same time, he recommends not holding back on steroids, as needed, while trying to minimize risks of glaucoma. “We’ve found in our studies that we can reduce the risk of complications such as cystoid macular edema by 80 percent when we treat these patients preoperatively with oral steroids,” he observes. “I’d say that perioperative treatment with steroids is extremely important for achieving a good outcome for these patients.” Sub-Tenon’s injection or intravitreal injection of steroids just before surgery or at the time of surgery may prove to be a safe alternative for patients who can’t tolerate oral or local steroid treatment, he adds.

“Typically, with any of these treatments, we’d like to have the steroids working and on board for at least a few days before the surgery so that they help to minimize postoperative inflammation,” he adds.

Dr. Werner is always looking for signs of uncontrolled glaucoma. “Investigate for a history of steroid response or other episodes of increased pressure, especially after a flare-up or a previous intervention, such as cataract surgery in the fellow eye,” he says. “You may stir up inflammation with your surgery, and the patient may become too dependent on steroids for a period of time. You’ll want to look carefully at any glaucomatous damage and how effectively you’re able to control the intraocular pressure in the perioperative period.”

In these patients, he says, a flow-restricted tube shunt, such as the Ahmed valve, may be a good choice to bring the pressure down quickly. “This will also reduce the potential for the development of hypotony, which is another risk in this patient population,” he adds.

Varied Approaches

Dr. Donnenfeld varies his approach to glaucoma before surgery. “If a uveitis patient has moderate glaucoma, sometimes just managing the cataract well—performing atraumatic surgery—may be sufficient to control intraocular pressure postoperatively, especially if there’s an occlusive pupillary component,” he points out. “But if there are significant pre-existing conditions, such as visual field loss or significant intraocular pressure, a glaucoma care plan has to be incorporated at the time of cataract surgery or after the surgery. I usually do this with the aid of a glaucoma specialist in our practice.”

Using New Treatments Judiciously When considering therapeutic options for patients with uveitis, Dr. Werner encourages physicians to consider the guidance derived from the MUST (Multicenter Uveitis Steroid Treatment) Trial.1 Patients who underwent cataract surgery were compared to patients who received either systemic anti-inflammatory treatment or placement of the Retisert implant. More than half of patients had posterior involvement of their uveitis before cataract surgery. Both groups achieved good visual acuity overall, with no difference between groups after risk adjustment, he says.“Notably, however, the number of patients in the trial as a whole who both developed glaucoma and who required glaucoma surgery was significantly greater in the group that received the Retisert implant,” he says. “I think there is definitely an important role for the implant, but it’s critical to plan for or deal with these issues, either proactively (with a combined cataract-glaucoma surgery) in patients at high risk, or later on, if the pressure proves uncontrollable. Small studies have also demonstrated good outcomes in Retisert patients who have tube shunts inserted.”2,3 On the other side of this issue, he notes, is the health risk of systemic immunosuppression, which may not be apparent in clinical trial reports. “So you always have to balance risks and rewards with each patient,” Dr. Werner adds. 1. Brady CJ, Andrea C, Villanti AC, et al. Corticosteroid implants for chronic non-infectious uveitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;2:2. 2. Chang IT, Gupta D, Slabaugh MA, et al. Combined Ahmed glaucoma valve placement, intravitreal fluocinolone acetonide implantation and cataract extraction for chronic uveitis. J Glaucoma 2016;25:10:842-846. 3. Ahmad ZM, Hughes BA, Abrams GW, et al. Combined posterior chamber intraocular lens, vitrectomy, Retisert, and pars plana tube in noninfectious uveitis. Arch Ophthalmol 2012;130:7:908-13. |

Dr. Donnenfeld says he’s found that a trabeculectomy tends to “scar down” unless he’s very aggressive with anti-metabolites. “My preferred therapy here is the use of tube shunts for most of these patients. However, I want to make sure the tube shunt isn’t clogged during surgery and that it’s sufficiently far enough away from the cornea that it doesn’t damage the cornea.”

In a patient with mild inflammation and a good angle, he continues, “I’ll still place a MIGS device. The MIGS can result in clogging (of the angle), so, again, I defer to the judgment of one of our glaucoma specialists on what to do under these circumstances.”

He also emphasizes the importance of watching for steroid responders. “Sometimes, the anti-inflammatory agents can increase intraocular pressure significantly, prompting me to titrate my steroids,” he says. “In general, though, I’d rather use my glaucoma therapy to reduce the pressure than reduce my steroid therapy and run the risk of the patient developing postoperative uveitis that can make the glaucoma worse.”

As needed, he uses beta blockers as first-line postop glaucoma therapy, followed by adrenergic blockers. “I reserve prostaglandins for later in therapy,” he says. “And I’m very quick to refer these patients to a glaucoma specialist if glaucoma becomes a problem postoperatively.”

Increased IOP in these cases may also result when inflammation overwhelms the drainage system of the eye when the patient undergoes steroid treatment or because of a combination of these factors, according to Dr. Werner. “These patients may have pre-existing issues with their drainage systems, which should be considered ahead of time,” he adds.

For concerns about IOP, he continues, a tube shunt with a flow-restricted mechanism has a good track record. “That being said, there is emerging evidence that angle surgery, such as a goniotomy, may help uveitic glaucoma patients. Long-term follow-up studies may clarify the role of these procedures in the future,” he says.

Confronting the Cataract

Dr. Werner says the cataracts he extracts from these patients’ eyes are often very challenging. “The surgery may be associated with small pupils, posterior synechiae and pupillary membrane, as well as white cataracts,” he notes. “These cases often require careful preoperative planning. Also keep in mind that more manipulation during surgery may augment the postop inflammatory response.”

Macular edema can also be a concern. “I always get an OCT preoperatively for these patients,” Dr. Donnenfeld notes. “That’s when I might elicit the support of a retinal colleague, who can inject an intravitreal steroid.”

Besides managing risks posed by a cataract patient’s uveitis and glaucoma, surgeons note that customized approaches may be needed for the cataract. “A mild cataract obviously calls for different measures than a case with additional complications, such as synechiae and a small pupil,” says Dr. Al-Aswad. “I had one patient whose capsule was literally attached to the inflammation, to the point where I couldn’t separate the iris from the capsule. I had to put in a Malyugin ring in the iris and the anterior capsule at the same time to hold them in place.”

|

|

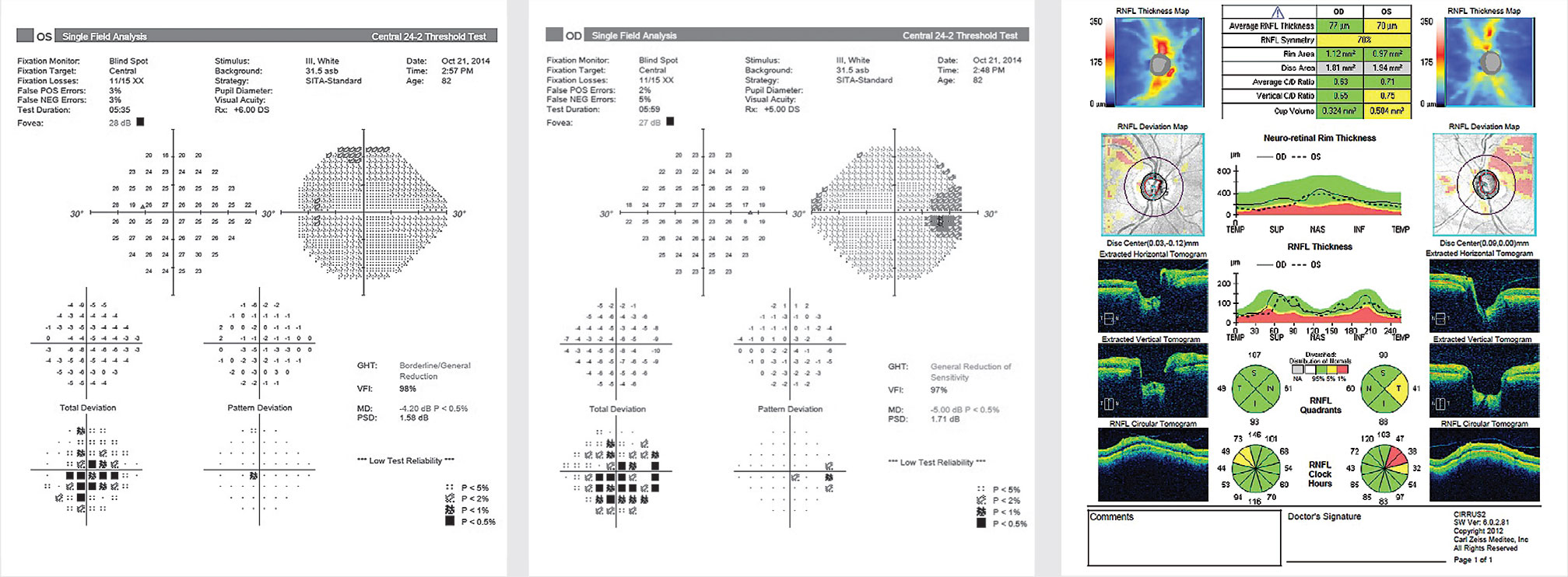

From left: Figures 3, 4 and 5. An 82-year-old female uveitic patient with long-standing rheumatoid arthritis presented with a history of chronic iridocyclitis OU, controlled on topical steroids, preperimetric glaucoma, visually significant cataracts and posterior synechiae OU. Her BCVA was 20/80 OD and 20/60 OS, and her IOP was 26 mmHg OD and 30 mmHg OS. Shown are visual fields in the left and right eyes and OCT of the RNFL OU (Figure 5). She underwent sequential phacoemulsification with lysis of synechiae, placement of an Ahmed implant (primed and ligated with 7-0 vicryl), an “orphan” trabeculectomy and sub-Tenon’s triamcinolone (20 mg) OU. Three years postop, her eyes were quiet, BCVA had improved to 20/50 to 20/70 OD, 20/25 to 20/50 OS, and IOP had decreased to 8 mmHg OD and 9 mmHg OS without topical medications. Click image to enlarge. |

She notes that the sustained-release dexamethasone and fluocinolone implants have been very helpful to her before surgery. “Pred Forte or systemic prednisone can also help before, during and after surgery,” she adds.

Dr. Donnenfeld says he also is frequently challenged by small or irregular pupils with anterior and posterior synechiae in this setting. “Some of the most challenging cases will involve seclusio pupillae or occlusio pupillae,” he says. “I always use a peribulbar block for surgery because I never know how the cases are going to end up, and I want to make sure the patient is comfortable.”

He strives to maximally dilate these patients preoperatively. Sometimes, he adds, he’ll turn to using Healon 5 (Johnson & Johnson Vision) to create space. “I use the pupil expanders, such as an I-Ring, Malyugin ring or iris hooks, depending on the severity of the pupillary block,” says Dr. Donnenfeld, who also resorts to microforceps when the pupil is “completely bound down,” adding, “In these cases, I will actually perform a small peripheral iridectomy and use viscodissection under the iris and a spatula to more efficiently break up synechiae and help restore angle anatomy.”

While using Trypan Blue to improve visualization, he strives to make the capsule an effective size, avoiding capsular phimosis, and he then implants his IOL into the capsular bag. “Of course, these patients also have zonular weakness from prolonged inflammation,” he adds. “If I have any concerns about that, I’ll use the capsular tension ring as well. I like to use a hydrophobic acrylic lens instead of a silicone lens, which can be problematic in these patients.”

Dr. Donnenfeld says he administers a subconjunctival steroidal injection at the conclusion of each case. “If there’s a vitrectomy for some reason, I also add intraocular triamcinolone, not only to visualize the vitreous but to reduce postoperative inflammation,” he says.

“I believe this is a case in which using the implantable drug delivery systems, such as the dexamethasone intraocular suspension 9% (Dexycu, EyePoint Pharmaceuticals) or the dexamethasone ophthalmic insert 0.4% (Dextenza, Ocular Therapeutix) can really play a significant role, helping to achieve maximum anti-inflammatory effects.”

Dr. Kedhar, who also often struggles to maintain visualization when operating on these patients, relies heavily on capsular staining dyes, when necessary.

“The use of capsular staining dyes can also improve your surgical technique in these patients,” he says. “The use of microincisions has also made a big difference to us as well. Instruments such as the Duet-style forceps from MST [MicroSurgical Technology] have enabled us to improve the surgical technique we use to remove the cataract.

“Of course, I would also agree that control of the inflammation is a paramount consideration during every one of these surgeries that we do,” he continues. “Besides immunosuppressive medications, local drug delivery of steroids, including difluprednate and the dexamethasone and fluocinolone implants, have been helpful to us. The longer-acting agents that provide the patient with more sustained control of inflammation are the most helpful in these situations.”

He notes that another positive development that’s made it possible to improve the care of these patients is the availability of better imaging modalities. “The widespread use of optical coherence tomography imaging to monitor for macular edema in these patients, both preoperatively and postoperatively, has improved our ability to achieve good outcomes,” he says.

The Case for Clear Cornea

Dr. Kedhar says he typically uses standard clear cornea phacoemulsification surgery in these cases. Because of the surgical challenges associated with poor visualization of the capsule and the red reflex in these patients, as well as responding to miosis, or posterior synechiae contributing to a small pupil, he says that he prepares for any eventuality, keeping Malyugin rings, I-Rings, iris hooks and capsular dye at the ready.

“We also have a capsular tension ring available for these cases,” he notes. “I recommend that surgeons always have a backup lens on hand when doing these procedures, too. You may not be able to place a one-piece lens in a capsular bag in these patients, so having a three-piece lens available is important.”

|

Before surgery, Dr. Kedhar insists on having every preop patient undergo an OCT scan. He also ensures that each patient experiences no macular edema for one month preoperatively, and is inflammation-free for at least three months before the cataract operation.

“I also try to get an endothelial cell count, if possible,” he says. “I want to look closely at the patient’s cornea. Many of these patients will have chronic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction or endothelial cell loss. Besides helping to identify preoperative keratopathy, by taking these steps, I can more adequately prepare patients for the potential need for future surgery.”

Shared Success

More than most situations in eye disease, the performance of cataract surgery in patients who have uveitic glaucoma calls for coordination among all of the subspecialities of ophthalmology and beyond.

The surgeons who are doing the cataract surgery can take advantage of the expert advice, support and collaborative care efforts of glaucoma, retinal and uveitis sub-specialists, as well as rheumatologists and other medical specialists.

“The most important factor in taking the best care of these patients is communication among members of the team,” says Dr. Kedhar. “For example, if a patient has a rheumatologist on board providing treatment for uveitis, informing the rheumatologist that you’re going to proceed with cataract surgery—and that it could cause a flare-up of inflammation—will allow you to come up with a strategy to manage the patient. The rheumatologist won’t be caught unawares by the inflammation flaring up after the surgery. The same thing holds true for the uveitis specialist, who can provide insights into trying to manage the inflammation around the surgery. Working together lets us help these patients better than ever.”

Dr. Werner is a speaker for Bausch + Lomb. Dr. Donnenfeld is a consultant for Allergan, Alcon, Novartis, Glaukos and Johnson & Johnson Vision. Drs. Al-Aswad and Kedhar report no relevant financial relationships with makers of products mentioned in this article.

1. Mehta S, Linton M, Kempen JH. Outcomes of cataract surgery in patients with uveitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Ophthalmol 2014;158:4:676-692.e7.