Although trabeculectomy is less-often performed than it once was, due to a vastly expanded pool of glaucoma surgical options, it’s still one of the most prominent and enduring procedures in glaucoma. One potential drawback of a bleb-producing procedure like trabeculectomy is the possibility of bleb-associated discomfort, or dysesthesia. This can happen shortly after surgery or many years later. It's something glaucoma providers should be able to recognize and treat to optimize patient care and quality of life.

Here, I’d like to discuss some of the causes of bleb dysesthesia and the seven different approaches (beyond simple, conservative treatment) that surgeons commonly use to address this type of problem.

Understanding Dysesthesia

Unfortunately, there’s no exact definition of bleb dysesthesia. In general, you can think of it as a spectrum of symptoms, including ocular discomfort, that patients may feel after filtering surgery. Those symptoms include tearing, pain, ocular surface irritation (for example, foreign-body sensation) and/or persistently fluctuating vision—especially when the patient blinks.

Which patients are most likely to end up with a bleb dysesthesia complaint? Donald Budenz, MD, at Bascom Palmer did a study investigating this question;1 he found that factors often associated with complaints of bleb dysesthesia included:

— younger age;

— a superonasal bleb;

— poor lid coverage of the bleb; and

— bubble formation at the bleb-cornea margin when the patient blinks (this is more likely to occur when there’s a steeper angle where the cornea ends and the bleb starts).

Surprisingly, having a very high bleb wasn’t a significant risk factor.

Corneal dellen (focal thinning in the cornea) can also cause a lot of irritation; it's more likely to occur in patients with a poor tear film or pre-existing dry eye and a superonasal bleb.

Fortunately, it’s rare that patients experience symptoms severe enough to require invasive intervention after trabeculectomy or any bleb-forming procedure. Nevertheless, it does occasionally happen, and, it can occur at any time postoperatively, from months to many years after the original surgery.

Helping the Patient

When a patient first comes in complaining of bleb dysesthesia, I want to know how long it’s been since they had the surgery. If it’s only been two or three months, I’m likely to wait to do anything to modify the bleb because it might remodel as the eye heals and forms scar tissue. But if a patient comes in and says she had the bleb surgery 15 years ago and has had symptoms for the past five years, I’ll begin with conservative treatments such as artificial tears or gel formulations. If those conservative measures fail and a patient has had long-standing symptoms, that’s a patient who’s more likely to need surgery. The chances of the bleb remodeling at that point are quite low.

In many cases, conservative management with tears or gels will be sufficient; they help to smooth out the ocular surface and give the patient relief from the symptoms. Some physicians will prescribe NSAID drops as an additional non-surgical option. I don’t use this approach for several reasons: NSAIDs don’t target the problem; patients often have discomfort when using the drops; and long-term use can be associated with unwanted side-effects. Use of a bandage contact lens may be helpful for reducing patient symptoms and compressing the bleb, but this is typically only a short-term solution.

Less-invasive treatments such as thermal laser application and autologous blood injection have been used for treatment of bleb dysesthesia. Personally, I don’t use these methods as I feel the outcomes are less predictable than those achieved with a more refined surgical approach.

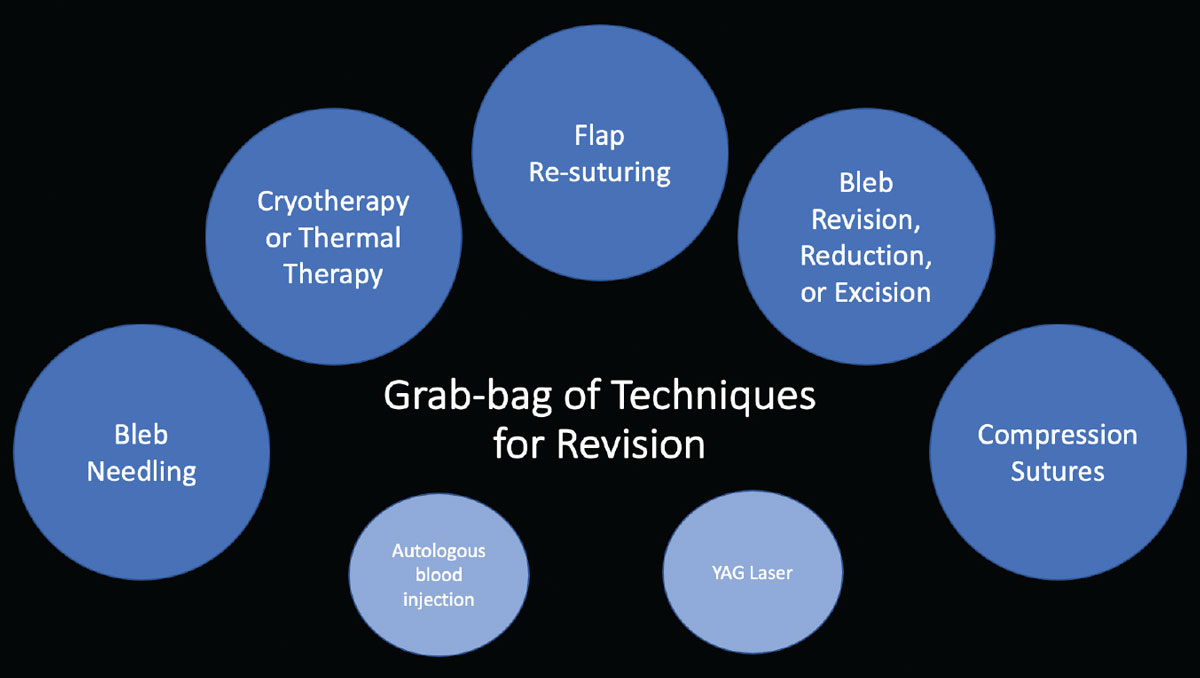

If your patient fails conservative treatment, often the next step is surgical revision, and there’s no single approach that’s always best. That’s partly because there are so many different causes of bleb dysesthesia. It could be the result of a very diffuse bleb; it can be caused by a dellen formation (a focal dehydration in the cornea, which causes a lot of irritation); it could be because the bleb is very nasal, which is often poorly tolerated, or because the bleb is overhanging on to the cornea; and/or the result of fluctuating vision. Furthermore, there could be a component of overfiltration, leaving the intraocular pressure on the low end; that will certainly impact how you choose to address the situation. So there’s no single “best way” to address bleb dysesthesia. The result is a grab-bag of possible treatments hoping to achieve a similar outcome: a functional surgery that’s well-tolerated by the patient.

Surgical Approach Options

|

| Click image to enlarge. |

Once conservative treatment has failed to provide relief, surgery may be the next step. While there are many approaches to surgical treatment, one of these seven options may help:

• Bleb needling. In some cases posterior scarring causes a very anterior bleb to be thin-walled and form a small pocket of fluid which can often overhang onto the cornea. This encapsulation can also interfere with bleb function, causing an elevated IOP. In this situation, bleb needling is a great way to encourage the bleb to be more diffuse and low-lying, and it can also help to reduce elevated IOP by breaking up some of that scar tissue and encouraging posterior flow.

If you do bleb needling for dysesthesia, it’s important to inject an antimetabolite such as mitomycin-C or 5-FU at the same time. If you don’t, the posterior scarring is likely to return.

• Flap resuturing. Some blebs that cause discomfort for the patient may be very large; this is often accompanied by overfiltering, and may be associated with a low IOP as well. In that situation, I like to take down the conjunctiva and resuture the flap to reduce the amount of aqueous flowing through the flap. This helps to reduce the bleb size and may help resolve the patient’s dysesthesia, as well any excessively low IOP.

• Compression sutures. Another way to deal with a really large, diffuse bleb is by putting in compression sutures. There are many successful techniques for placing compression sutures. One technique developed by Paul Palmberg, MD, for accomplishing this is very popular. Using a 9-0 or 10-0 nylon, the surgeon makes a mattress suture from the cornea over the bleb to the episcleral or Tenon’s, parallel to the bleb; the suture, or sutures, compress the bleb.2 The hope here is that you’re going to create an adhesion between the conjunctival bleb tissue and the underlying tissue, limiting the extent of the bleb. You can remove the sutures one to four weeks after the surgery. (This approach can also help with bleb overfiltration.)

• Cryotherapy. This technology can be helpful for bleb remodeling. I like to use this technique for blebs with significant nasal extension. One technique is to create a window in the conjunctiva in the nasal area where the bleb has extended. The surgeon can then use cryotherapy to secure down the edge of the window, encouraging adhesion to the underlying sclera. The scarring that results helps to limit the nasal extension.3,4 There are other creative ways to use cryotherapy alone or in combination with suturing techniques to limit the breadth of the bleb.

• Surgical excision. Another useful approach, especially when the bleb is very anterior, thin-walled, avascular, high and irritating to the patient, is to excise all of the bleb tissue and then pull healthy conjunctiva forward and suture it down. The hope is that this approach will allow for a more diffuse bleb.

• Autologous blood injection. This technique, sometimes used to address a late-onset bleb leak, isn't very popular today; in fact, I don’t personally know of any surgeons that still inject autologous blood for bleb dysesthesia. It’s thought that injection of blood encourages a fibrotic response and thereby limits flow and perhaps could encourage scarring.5 In my experience, surgery is a more refined and controlled way to address bleb issues. Furthermore, autologous blood injection could cause bleb failure.

• YAG laser. Like autologous blood injection, this isn’t often used to address bleb issues today. Using a continuous-wave multimode (frequency-doubled) neodymium-YAG laser, creating a thermal response in the tissue, the laser is applied in a grid-like pattern over the bleb to encourage the tissue to shrink down. (Note: It’s difficult to remodel and shrink tissue in the bleb without use of methylene blue or gentian violet ink—applied with a surgical marking pen on the dry bleb surface—as a chromophore for the laser, which enables adequate absorption of laser energy in the bleb.) This approach can be effective as a way to lower the height of the bleb or remodel steep edges. (In this situation, surgical revision is an alternative to laser revision of the bleb.)

Another option is to completely close the existing bleb and perform a different type of pressure-lowering surgery instead. I’ve had some patients request this option; because of long-standing discomfort, they don’t want any type of bleb-forming procedure. This could mean suturing the flap shut, excising the avascular tissue and possibly putting a corneal or scleral patch graft over the old flap site.

Closing down a trabeculectomy can result in a dramatic rise in IOP, so this will need to be considered in surgical planning. If you don’t immediately do another IOP-lowering procedure, the next day you’re going to see that patient with a very high pressure. Most of the time, you may have to do an additional IOP lowering surgery at the same time as, or soon after, you close down the existing bleb. In my practice, I’d typically consider placement of a tube shunt at that time.

Which surgery you choose to replace the trabeculectomy in this situation depends on numerous factors, including how bad the glaucoma is and how low the pressure needs to be. In most cases, if the patient has serious glaucoma, I switch to a tube or some other non-bleb-forming procedure. (Some surgeons might consider implanting a XEN shunt, which can produce a more posterior bleb; in theory that might be associated with less discomfort. But at this point I don’t think we have enough data to know whether a XEN bleb would be less likely to cause bleb dysesthesia.)

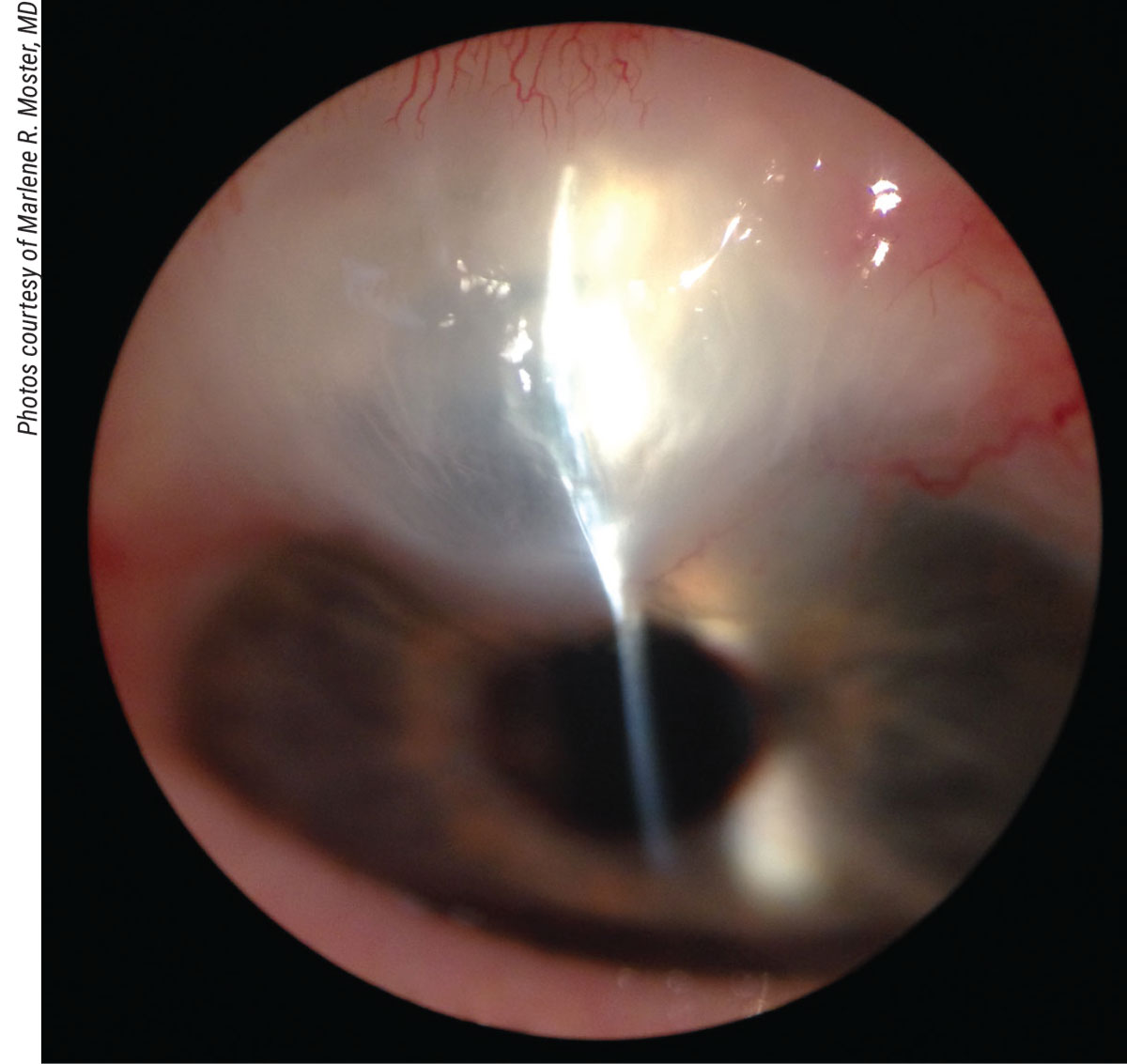

|

| A thin-walled cystic conjunctival bleb with corneal overhang. This could be addressed via bleb revision with excision of the corneal overhang and resection of the avascular tissue, with anteriorization and suturing of posterior, healthy conjunctiva to the limbus. |

Does Treatment Work?

One problem when managing bleb dysesthesia is that it’s hard to predict the outcome; every case is different and the management varies tremendously. (This also makes it difficult when you want to study the treatments and outcomes.)

One way we can address this is to look at large sets of data; this can give us a general idea of the outcomes of such procedures. There are some large studies that look at bleb revisions and show subgroup analyses of the revisions that were done to address bleb dysesthesia. We’ve learned some useful information from these studies that can help us guide our patients when we’re counseling them regarding surgical options for treatment:

— Retrospective studies suggest that 50 to 100 percent of patients treated for bleb dysesthesia achieve success. This means it may be safe to suggest that at least half of your patients are likely to get relief following treatment.6

— In patients who have a bleb revision, 9 to 15 percent are going to need more surgery to lower the pressure. That’s actually pretty encouraging; even though you’re modifying the original surgery, not that many of these people go on to need more surgery. (This is obviously not applicable when you shut down the original trabeculectomy.6)

— Occasionally, patients who undergo revision for dysesthesia will require a re-revision when the first revision isn’t successful. Some of the retrospective data suggests a little over 10 percent of patients may undergo a second revision for dysesthesia.7 (Patients may be more reluctant to undergo a second revision.)

— Most encouraging, the majority of patients who undergo revision for bleb dysesthesia experience little to no change in vision from the original procedure.7 In fact, some patients may experience a slight improvement in vision, which may be due to a reduction in astigmatism. So you can be somewhat reassured that you’re not compromising the patient’s visual acuity by going in there and modifying the bleb.

Note that these results were obtained by experienced surgeons. Having experience helps the surgeon choose among the many options and combinations of treatments for the patient’s specific bleb problem. It’s an art to choose the best approach, because—as noted earlier—- there’s no single cookie-cutter treatment for this problem that will work for every patient.

One Final Thought

With any patient in this situation, it’s important to manage expectations. You need to explain that your goal is to reduce their symptoms, and that more than 50 percent of patients do get relief, but the other half may continue to have symptoms. In short, your patient needs to understand that there’s a chance the surgery could fail to help them, and they might need further surgery later on, either to lower the pressure or to relieve symptoms.

In any case, glaucoma can be a challenging diagnosis for patients, and it’s important for us to listen to our patients and do what we can to improve their quality of life as a part of the treatment of their disease. We can often get the pressure lower, but we always have to remember that we’re treating the person, not just the eye. In most cases, the patient will get some relief as a result of your efforts, and you may improve their glaucoma control as well.

Dr. McGlumphy is an assistant professor of ophthalmology at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore. She has no financial interest in any product mentioned in this article.