Scientists at Harvard Medical School have completed a proof-of-concept study showing that it’s possible to reverse both age-related vision loss and eye damage similar to that caused by glaucoma, in mice, using epigenetic reprogramming.

This new approach is based on a recent theory about the cause of the gradual functional failure we associate with aging. The hypothesis is that this failure is caused by deterioration of the epigenome, a system that activates specific genes in our DNA, causing cells to serve specific purposes. The epigenome appears to accomplish this by methylation—attaching methyl groups to the DNA. Early in life the epigenome triggers patterns of methylation that activate the appropriate genes, but as the epigenome deteriorates, the wrong genes are activated—or the right ones fail to activate—leading to signs and symptoms associated with diseases of aging.

|

In this study, described in the early December 2020 edition of Nature, the researchers theorized that if a virus could be used to deliver genes into cells that would replace faulty methylation patterns with the original, early-life methylation patterns, the dysfunction of the cells might be reversed. This would then cause healthy cell function to resume. The effect could be thought of as a reversal of the aging process.

The lead study author, Yuancheng Lu, PhD, based this work on the Nobel-Prize-winning work of Japanese stem cell researcher Shinya Yamanaka. Yamanaka identified four transcription factors (genes) that can be used to erase epigenetic markers, returning them to their primitive embryonic state. Studies found that the result of applying all four factors caused too much regression, so Dr. Lu and colleagues hypothesized that omitting one of the four factors would reset the early-life epigenome safely. They were able to achieve this result in petri dishes, so the next step was to see if it would work as well in vivo.

Partnering with Harvard’s professor of genetics David Sinclair, PhD, and Zhigang He, PhD, a professor of neurology and ophthalmology at Boston Children’s Hospital, Dr. Lu conducted a series of experiments:

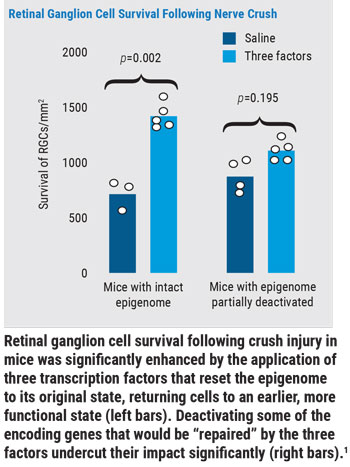

- First, they used an adeno-associated virus to deliver the gene combination to retinal ganglion cells of adult mice with optic nerve injury. The result was a two-fold increase in surviving retinal cells and a five-fold increase in nerve regrowth. (Graph, above.)

- Following the success of that experiment, the team partnered with colleagues at Schepens Eye Research Institute (part of Massachusetts Eye and Ear) and the treatment was applied to mice that had lost vision after being subjected to a model of glaucoma. The treatment led to increased nerve cell electrical activity and an increase in visual acuity.

- Next, they treated mice whose vision had diminished due to normal aging. After treatment, optic nerve cells regained the electrical signaling seen in young mice, and testing showed that the mice had regained their youthful vision.

So far, treating mice for a year with the combination gene therapy has shown no negative side effects. The researchers say that if their findings are confirmed, they hope to initiate trials in humans within two years.

Asked how many treatments might be required to restore vision—assuming the approach continues to be confirmed as safe and effective—co-author Bruce Ksander, PhD, says that remains to be determined. “We’re currently determining how long the increase in visual function is sustained following a four-week expression of the OSK genes in retinal ganglion cells,” he explains. “However, since this gene therapy uses a doxycycline inducible vector, it would be possible to induce a second expression of the OSK genes by delivering doxycycline to the retina. Therefore, we may achieve long-term effects on visual function by periodic reactivation of the vector.”

Dr. Ksander notes that this epigenetic repair approach will probably have limitations. “We predict that OSK gene therapy is reprogramming retinal ganglion cells that have lost function but have not yet undergone apoptosis,” he says. “Therefore, the ‘window of opportunity’ for treatment would be determined by how long dysfunctional retinal ganglion cells survive before dying by apoptosis.

“I hope that with the addition of more pre-clinical studies, we’ll be closer to translating this approach to the clinic to treat glaucoma patients,” he adds. “I also hope that epigenetic reprogramming is shown to be effective in restoring function to other types of cells in the retina, such as photoreceptors, retinal pigment epithelial cells and Müller cells.” REVIEW

1. Lu Y, Brommer B, Tian X, et al. Reprogramming to recover youthful epigenetic information and restore vision. Nature 2020;588;124-29.

A Note from Our Publisher, Michael Hoster

Dear Doctors,

While the first few months of the new year may, in fact, seem a great deal like the previous several months of the old year—we have, if nothing else, a renewed sense of hope and optimism that 2021 will mark a stark turning point in humanity’s battle against the COVID-19 pandemic.

Fortunately, during the past 10 months, we’ve all continued to experience precious moments of accomplishment, reward and joy—even if these instances frequently have been dotted with a Mark McGwire-sized asterisk. Perhaps a son or daughter graduated from college. (*just two family members were permitted to attend.) Or, you purchased a new home. (*you had to tour the house virtually.) The same is true for me. In July, I was humbled and honored to be named publisher of the Review Group, following the retirement of my predecessor, mentor and friend, Jim Henne. (*during one of the most turbulent times our industry has ever faced.)

Throughout this period of enormous uncertainty, however, we’ve remained steadfastly committed to the development of novel, practical content intended to help you successfully navigate these trying times. And, I couldn’t be more proud of our efforts.

Along similar lines, I’m pleased to announce that Review has undergone its most comprehensive graphic redesign in the past 20 years. You’ll notice a bold re-imagining of our logo on the cover, and a modern aesthetic layout for feature articles and recurring columns. It’s all part of our tireless efforts to provide you with clinical advice you can trust—which also happens to be our new tagline.

A special thanks to Editorial Director, Jack Persico; Editor-in-Chief, Walt Bethke; Art Director, Jared Araujo; and Senior Designer Matt Egger for their exceptional creative talents and vigorous discipline in making this redesign possible!