The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has extended its COVID-19 public health emergency declaration for a fourth consecutive time, continuing waivers that make telemedicine a bit more practical for ophthalmologists until April 21. But glaucoma specialists say they need more than this flexibility to respond to the ongoing pandemic and prepare for future public health challenges. Because of a reliance on frequent in-office testing, many of them are experimenting with a hybrid of new and borrowed strategies to safely and efficiently manage patient flow.

“The crippling thing about telemedicine for glaucoma care is that it doesn’t enable IOP checks, visual fields and OCT scans that provide the critical information we need to follow,” says Peter Netland, MD, PhD, Vernah Scott Moyston professor and chair of Ophthalmology at the University of Virginia School of Medicine in Charlottesville. “Without that, we’ll risk missing something important. What doctors are saying when they do home visits is that they’re willing to miss a certain amount of change in the patient’s status. For us, we decided early on, as a glaucoma group, that we were going to try to provide protection for ourselves and our patients through standard, acceptable approaches at the point of care. We tried telemedicine, and we saw we didn’t get all the information we needed to make sure our patients were adequately monitored.”

Although some ophthalmologists are using scaled-down telemedicine to care for glaucoma patients, most are also adapting innovative new approaches. In this article, you’ll learn how detailed pre-visit telephone screening of patients, general medical advice, expanded staff responsibilities, consolidated evaluation-and-surgery visits, public health measures, drive-by pressure checks and visual fields and responsive approaches to fragile and apprehensive elderly patients are keeping glaucoma practices on a firm footing—and how you can incorporate some of these strategies, as needed, into your practice to optimize care of glaucoma patients.

Expanding Scope of Care

Most glaucoma patients, at the highest risk for COVID-19 infection due to their age, have recently been sheltered for long periods and may have lost friends or loved ones to the virus. When they venture from their homes or long-term care facilities to visit an ophthalmologist, they often fear the unknown as much as COVID-19, according to Brandon Baartman, MD, lead surgeon at Vance Thompson Vision in Omaha, Nebraska. This is one of the central challenges: Caring for patients most in need of a visit to your office, yet most at risk during a visit to your office. Instead of limiting these encounters to three tests, an examination of the eye and a discussion of medications and changes in vision, Dr. Baartman and his fellow specialists find themselves “putting on their general doctor hats” during these visits, he says.

“We find that we need to provide patients with an overview of COVID-19, including the symptoms and risks, and we need to go over other aspects of the virus, such as how and when to wear a mask,” he notes.

|

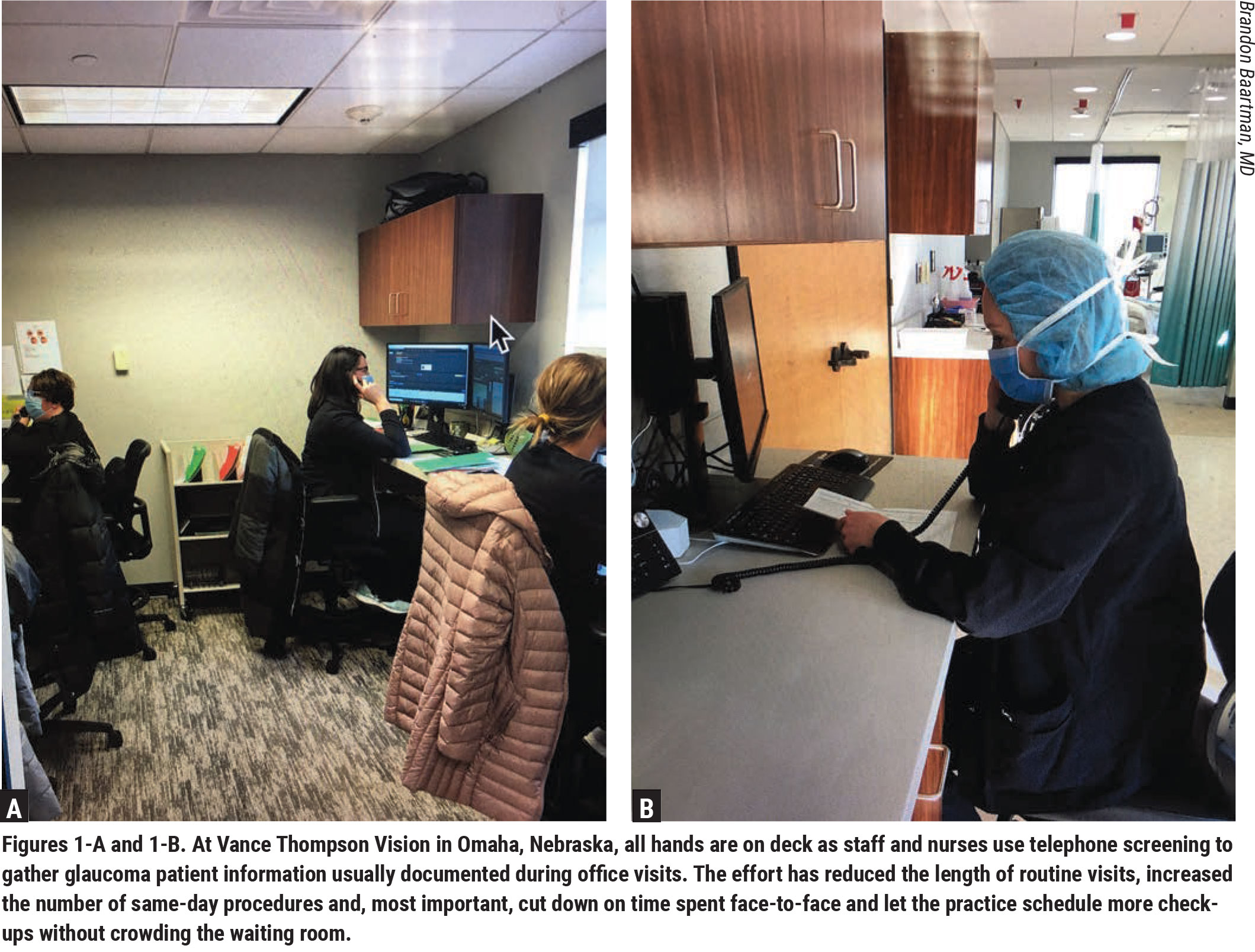

Even before the patient visits the center, the staff at Vance Thompson Vision visits patients’ homes by voice, conducting extensive telephone screenings and beginning patient education and assessments. “Collecting patients’ subjective history over the phone has allowed us to reduce the amount of time patients spend at our center,” says Dr. Baartman. “We can tighten up visits, save time in the pre-testing lanes and reduce clustering. Telephone screening makes sure we have all the information we need, including correct medical history and, in many cases, referring doctors’ notes. It also helps us establish a touch-point ahead of time.”

Like most practices recovering from a one-to-two-month COVID-19 shutdown last spring, the Vision Center has needed to increase patient volume, not only to meet the lingering needs of patients whose care had been delayed, but also to shore up the center’s bottom line.

“We couldn’t go back to 100 percent right away,” Dr. Baartman notes. “There was a slower ramp-up to our peak. Towards the end of the year, we really needed to take care of a lot of patients. We had to increase our availability, which we did. For example, I went from operating two days a week to three.”

Same-Day Procedures

Reconceiving glaucoma care in the era of COVID-19 has also meant increased emphasis on a program designed to consolidate evaluations and procedures into single visits at the Vance Thompson Vision Center, where the focus is on surgery more than the chronic care of glaucoma patients. The result of increased consolidated visits has been more efficiency, contributing to greater safety and efficacy.

“We call this our ‘see-and-do’ program, which has really gained traction,” says Dr. Baartman. “These are the cases in which we’ve traditionally evaluated patients, sent them home and brought them back for surgery. Now, we can combine their evaluations and procedures into one visit, provided we have enough preoperative information from their referring doctors.”

Dr. Bartman adds that the practice has expanded beyond surgery. “We’re also doing more same-day selective laser trabeculectomies, some of which are bilateral SLTs, which have become a lot more popular,” he notes.

He explains that same-day procedures have evolved into a “practice solidifier” for the center. “It’s been limiting the number of visits—the people coming in and out,” he observes. “See-and-do visits can be tricky to schedule, but they’re really meaningful for our patients and practice.”

Chronic Care

|

More than 350 miles from Omaha, Dr. Baartman’s colleague Deborah Gess Ristvedt, MD, provides chronic glaucoma care for “40 years’ worth of patients” in Alexandria, Minnesota. It’s a world away from Dr. Baartman’s setting in terms of adapting to the modern realities of glaucoma care and the COVID-19 environment. “What I’ve had to do is go through every single patient and decide which ones would need to be watched more closely and which ones could be rescheduled for three months out,” Dr. Ristvedt recalls.

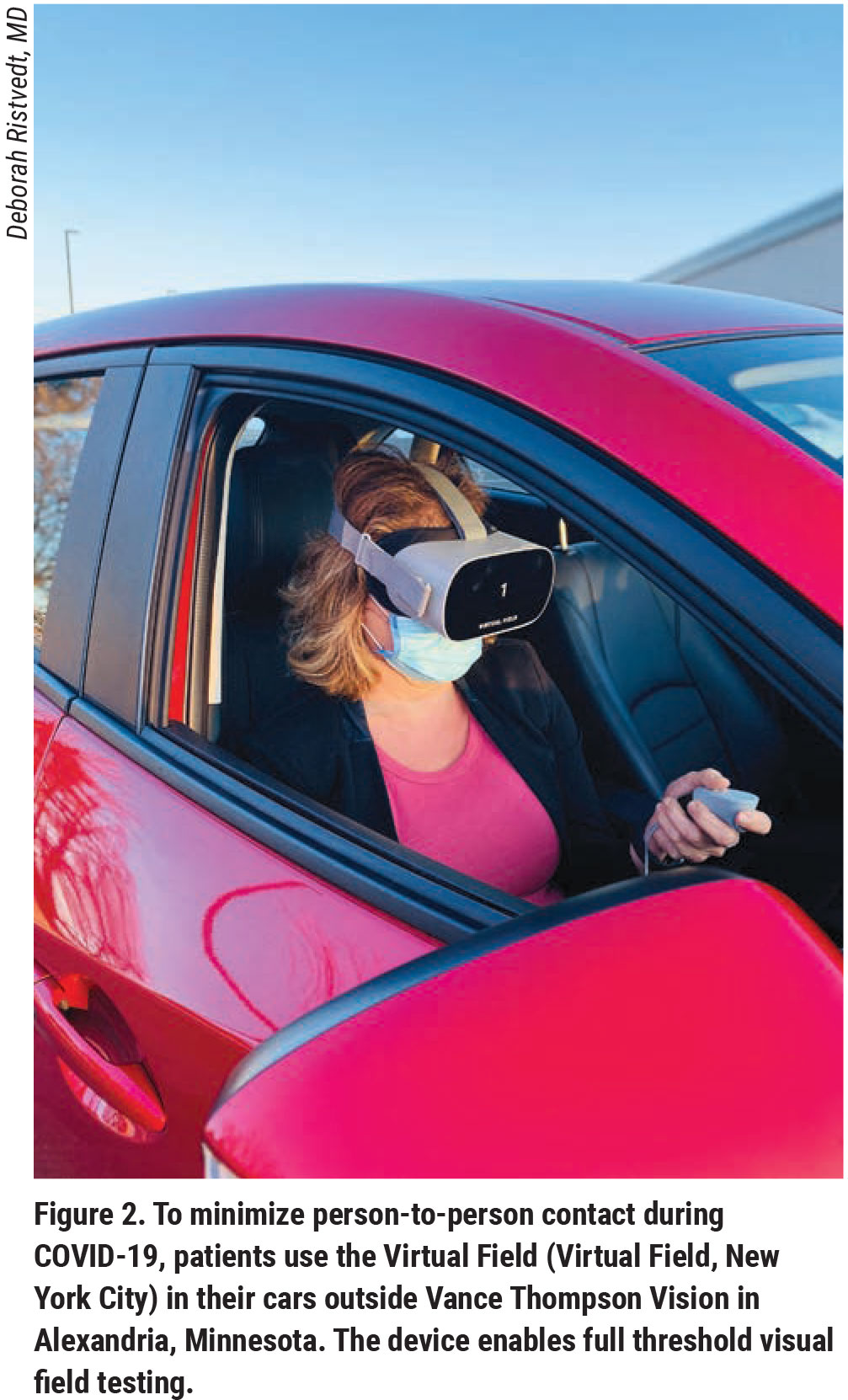

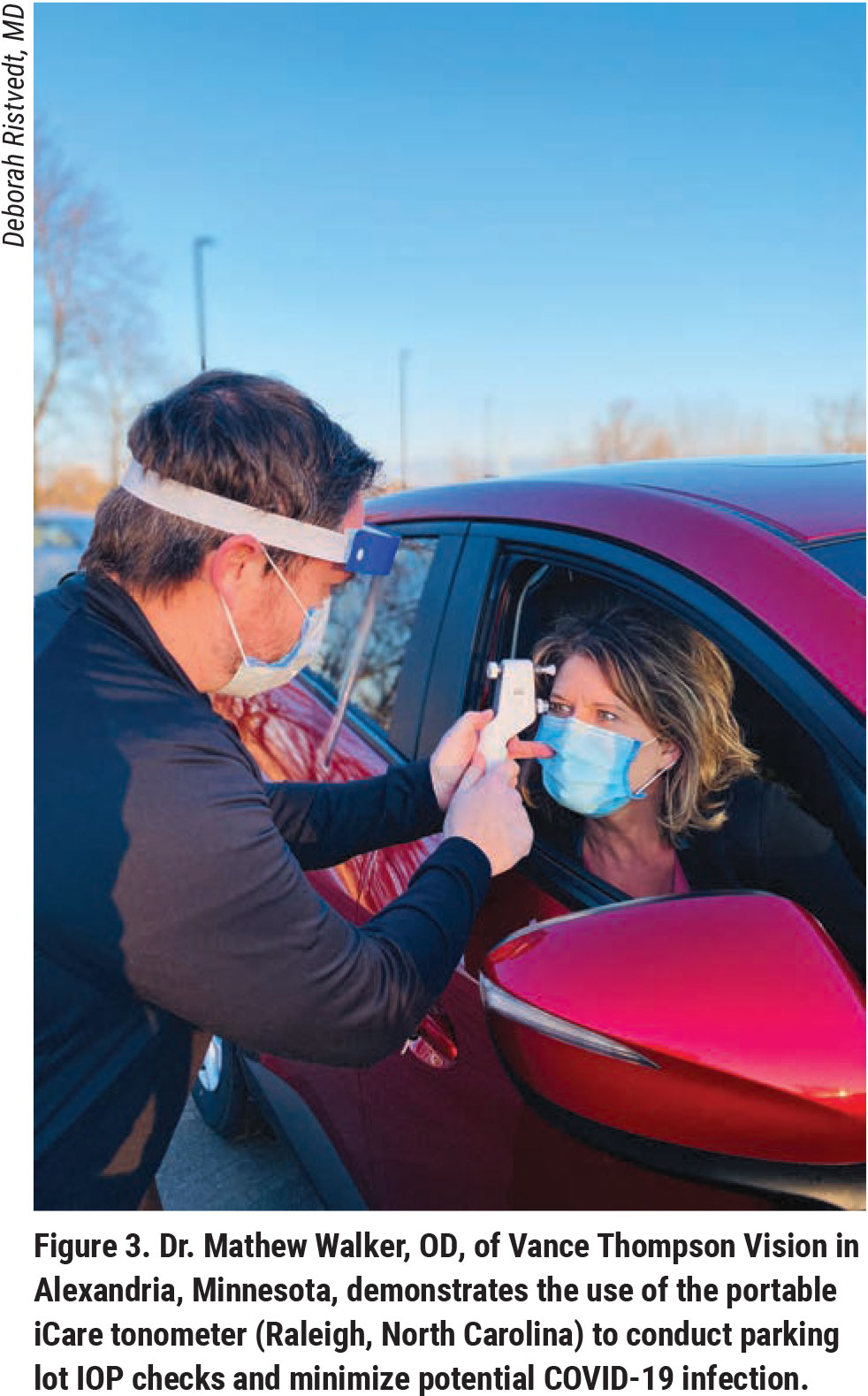

While completing this process, she has introduced IOP checks and portable visual fields to the practice parking lot. The IOP checks are made possible by the use of the non-contact iCare tonometer (Raleigh, North Carolina) and the visual fields are recorded on a handheld device called the Virtual Field (New York City). Some patients continue to undergo the tests while remaining in their cars.

“We’re able to use these instruments for patients who are nervous about coming into the office,” says Dr. Ristvedt. “The pressure checks have also been helpful when we want to make sure a patient is still stable, and they’ve enhanced our postoperative management, following MIGS or regular glaucoma surgery.” Checking visual fields in the parking lot has expanded the use of an instrument that’s normally used in the office for patients who have disabilities or who struggle to use a regular perimeter.

“The Virtual Field is easy to use and provides accurate visual fields,” Dr. Ristvedt adds. “It’s been ideal for this new setting.”

With her focus trained on chronic care, Dr. Rivstedt has tried to use telemedicine as much as possible. “We’ve noticed that the increased use of telemedicine by primary care physicians has increased the willingness and ability of our patients to give it a try,” she notes. “However, telemedicine is particularly difficult for our patients because most of them are elderly and have a hard time opening our email message, using the screen and following the process involved, including getting on the computer at the right time. Telemedicine is also very time-consuming.”

Nonetheless, concern that glaucoma patients could possibly not receive optimal treatment, benefit from needed treatment adjustments or, worse, go without treatment has been ever-present in the minds of Dr. Ristvedt and her colleagues. “Not being able to see patients in the way we were used to kind of opened our eyes and forced us to ask ourselves: Are we doing things in the right manner?”

After some deliberation, they decided on a hybrid approach to many patients, bringing them to the office for IOP checks, visual fields and OCT scans that included funduscopic viewing capabilities, enabling a view of the optic nerve. Being able to bill for these key tests, as well as those in the parking lot, has also enabled the practice to earn higher reimbursements that aren’t available through the use of telemedicine alone. After these abbreviated hybrid visits, Dr. Ristvedt says, “we collect the data we need and we follow up with patients by turning to telemedicine. This has really limited the time that patients spend in our office.”

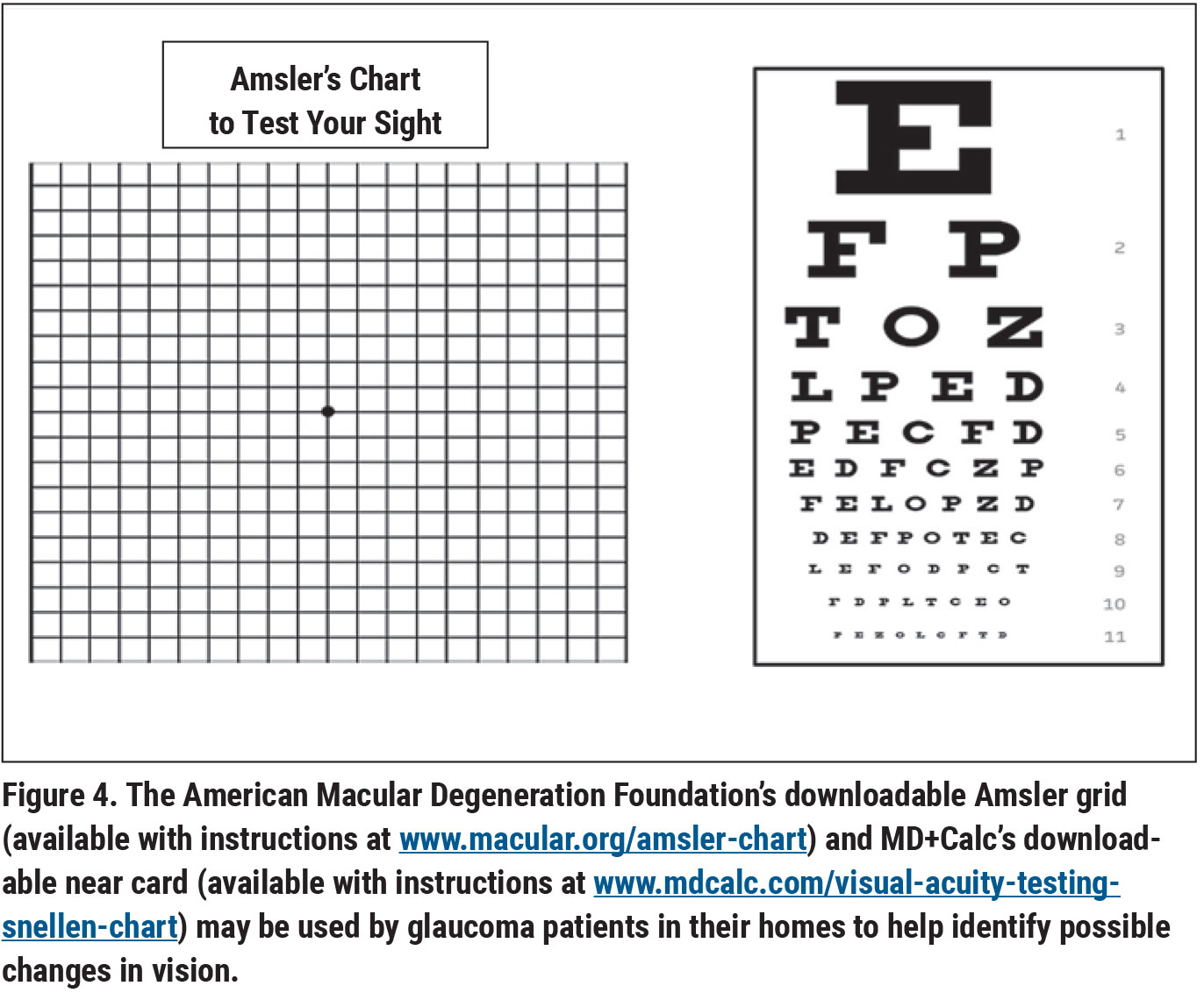

On telemedicine calls, Dr. Ristvedt and her colleagues ensure patients are using drops correctly and don’t have any concerns about their therapy or care. Patients are asked to use a downloadable near card and Amsler grid to help identify changes in visual status. “Telemedicine isn’t going away,” she adds. “It will continue to improve. But for now, this limited approach is the best we can do.”

Dr. Ristvedt says the intracameral injection of bimatoprost SR (Durysta), providing six months or more of treatment without drops, has also been helpful, assuring her and her colleagues that patients are continuing to receive treatment, even when they can’t be examined in a timely manner. “That implant couldn’t have come out at a better time,” she says.

Operational Challenges

|

Ronald Frenkel, MD, a glaucoma and retinal specialist who serves as medical director at East Florida Eye Institute in Stuart, Florida, says COVID-19 continues to present operational challenges, forcing glaucoma specialists to improvise in new ways. Many patients don’t schedule or keep appointments because they’re afraid of exposure to the virus, forcing his practice to reduce staff hours and manage the budget tightly, in light of reduced revenues. Patients who do come in are sometimes challenging to manage, often taking off their masks before he enters the room to examine them. “I have to tell them not to do that,” he says. “We put a sign on the door, but that doesn’t always work. Another thing we do is try to minimize the time spent in the exam room with the patient. We’ll look at test results away from the patient and then go into the room and explain the results. This adds to the time we need to set aside for each patient, but it increases safety.”

Another challenge: Masks usually don’t fit perfectly, he says. “One of our biggest issues is the fogging of the diagnostic lenses we’re holding up to look at the optic nerve,” he continues. “If it’s not the diagnostic lens fogging up, it’s our own oculars or glasses. The diagnostic lenses help me identify subtle differences on the optic nerve that aren’t always picked up by OCT scans or by the fundus camera. You can only use so many wipes or adjust your mask and take so many anti-fogging measures throughout the day. To me, this is a really big problem. I pride myself on being a pretty good diagnostician, but now I know that my exam is being compromised. There are no magic bullets. We just try to adapt to new situations as we go along.”

Adapting Quickly

Most practices have had to adapt quickly and expect to continue to need to do so, especially as their efforts relate to staffing and maintaining a safe environment. Even to this date, practices may be pursuing varying courses of action—possibly failing to optimally manage risk, according to Dr. Netland.

One often-overlooked issue is the potential need to modify your HVAC system, he notes. “If you don’t have adequate ventilation in your rooms, air droplets will build up, creating one of the most significant risks,” he says, noting that unidirectional flow ventilation (taking droplets out of the room) or a positive pressure air flow is needed, as opposed to rooms with recirculated air or no circulation. “We’re very fortunate because we have clinical engineering people who know the system we have. They also have special devices that measure airflow. If your airflow isn’t appropriate, you can mitigate or correct it by adjusting ventilation settings or, for recirculated air, using air filters. If you have to think about upgrading your HVAC, that’s a bigger job. But I’d suggest that it might be worth doing.”

Dr. Netland is quick to acknowledge that he isn’t a public health expert by any measure. “But I feel like I’ve had to develop public health skills that I’ve never had before,” he says. He recommends minimizing risks in your setting by following COVID-specific guidelines from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html) and the American Academy of Ophthalmology www.aao.org/coronavirus. He’s also relied on evidence-based approaches for ophthalmologists provided by the University of Pittsburgh1 and the Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem, Israel.2

The UVA clinic, where Dr. Netland and his colleagues care for patients, is staffed by more than 150 employees. When he first implemented public health guidelines in April of 2020, almost one quarter of these employees were lost to quarantine. “Losing nearly 25 percent of your work force for two weeks represents a pretty big hit,” he points out. “We suddenly didn’t have a stable workforce. Since then, we’ve aggressively managed our patient flow and practice patterns according to the guidelines, and we’ve had zero quarantines. Following the guidelines is not rocket science. You just have to learn to take simple but very important steps.”

|

Dr. Baartman says staffing has also presented unexpected challenges at his center. “COVID-19 has had a huge impact on our ability to staff our clinics and operating rooms,” he notes. “It wasn’t just because people were getting sick. It was because a lot of our staff have kids who couldn’t go to daycare or who have family members who were exposed to the virus. At any given moment, our staff has been down 20 percent. We’ve needed to empower employees to make independent decisions, when possible. Also, one of our core values is to be egalitarian, never letting anyone feel like he or she is above a certain role. That philosophy has served us well because people have moved into other roles when those roles have needed to be filled. We’ve developed a much stronger sense of sharing responsibility that’s helped keep us on our feet. That’s something we’ll emphasize going forward.”

The Days Ahead

As he considers an environment in which COVID-19 has been brought under control, Dr. Netland doesn’t envision a need to perform the same kind of screening and social distancing that his team currently uses. “But there are some things that we want to continue with,” he says. “For instance, we’re going to continue with Zoom meetings. We’ve found they’re much more efficient. We’ll also pay more attention to patient congestion in the waiting room. As we come out of this pandemic, patients are probably going to be a little more sensitive to overcrowding. We’ll need to be more sensitive to that, too. For example, we don’t want to have five doctors or techs standing around in the same room.”

He adds that influenza and other viruses will continue on a seasonal basis. “The peak number of deaths associated with coronavirus is higher than the number from influenza,” he says. “But it’s not by that much more during the height of the flu season. The modifications to our ophthalmic equipment, the airflow and the other protections that we’ve put in place will probably be used yearly to protect us during the cycles of the other infections that we deal with. We have mandatory influenza vaccinations at the clinic every year, but the vaccine is only 50-percent effective.”

He says the screening of patients for infection and constant sanitizing of hands, workspaces, equipment and areas touched by patients will continue. “We joke and say we’ve become alcoholics because we use so much alcohol to clean everything,” he says. “We’ll keep using wipes and hand sanitizers and cleaning the exam rooms and equipment between patient visits. The pandemic has raised our awareness of basic infection-control techniques. We want to have 100-percent compliance in all of these areas.”

Dr. Baartman envisions a future in which the doctor-patient relationship will continue to strengthen so that doctors can maintain a 360-degree assessment—one that focuses on a patient’s psychological, logistical and medical needs. Doctors and their staffs will need to be ready to continue to adapt, he adds.

“I think it would be a shame if we all went through this and didn’t learn something about ourselves, our practices and our ability to withstand the pressures of COVID-19,” says Dr. Baartman. “The most efficient way to deliver health care has become a priority, as have the best practices for staffing a clinic. We’ve learned to better understand the needs of others, including our staff and patients, while trying to accommodate and be more flexible. That’s really where I think our practice is headed. When the going gets tough, we really need to not just get going, but also to start listening to each other, better understanding needs, making changes and helping each other in any way we can.”

Drs. Netland, Baartman, Ristvedt and Frenkel report no financial relationships with companies that produce poducts or services related to the comments they offered for this article.

1. Williams AM, Kalra G, Commiskey PW, et al. Ophthalmology practice during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: The University of Pittsburgh experience in promoting clinic safety and embracing video visits. Ophthalmol Ther 2020;9:3:1-9.

2. Khaled Safadi K, Kruger JM, Chowers I, et al. Ophthalmology practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open Ophthalmol 2020;19;5:1.