Just a few decades ago, blepharitis wasn’t on most ophthalmologists’ dry-eye radar. “They didn’t realize how much it affects the tear film or patients’ quality of life,” says Mina Massaro-Giordano, MD, a professor of clinical ophthalmology and co-director of the Penn Dry Eye and Ocular Surface Center at the Scheie Eye Institute, University of Pennsylvania. “The pathophysiology is still poorly understood, but broadly, we understand blepharitis as eyelid inflammation. Inflammation in the lid triggers a cascade of disturbances in the bacterial flora and alters the quality of oil produced by the lid.

“Many patients just lived with miserable-looking lids and assumed they’d have to look and feel this way forever,” she notes. “Now we know that if we treat the lids, this results in a better tear film, which translates to improved vision. You also need a healthy tear film to take accurate measurements for lens implantation for cataract surgery.”

Blepharitis is one of the most common reasons patients seek care when they have issues with dryness or their ocular surface, says Guillermo Amescua, MD, associate professor of clinical ophthalmology and medical director of the Ocular Surface Program at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute Ocular Surface Center. “This is due in part to the number of possible causes for the disease, which include toxins, bacteria, allergies, mites, certain dermatologic conditions or drugs, and genetics.”

In this article, experts discuss their tips for diagnosing and managing blepharitis, and why patient education is vital for staving off dry eye.

The Gland Inquisitor

|

Blepharitis diagnosis and treatment begins with correctly identifying the underlying cause and addressing it appropriately. “It’s a clinical diagnosis,” says Bennie H. Jeng, MD, a professor of ophthalmology and chair of the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. “Anterior blepharitis often presents with ‘dandruff’ on the eye lashes or with flaky skin, whereas in posterior blepharitis, we see meibomitis, which influences dry eye.”

“In a case of seborrheic blepharitis, you’ll see crustiness or exfoliated skin along the base of the eyelashes,” notes Dr. Massaro-Giordano.

Additionally, Demodex folliculorum is a common cause but one not often addressed, Dr. Massaro-Giordano points out. “Patients can tolerate a certain number of those waxy collarettes at the base of eyelashes,” she says, “but after you hit a certain threshold they can be very disturbing to the patient and need to be addressed with the appropriate treatment. Antibiotics, steroids or ointments won’t get rid of mites. You need a targeted therapy for a full month to break their reproduction cycle and get rid of them.”

The failure of previous dry-eye treatments are sometimes the result of an undiagnosed Demodex infestation. Dr. Massaro-Giordano says she’s found success with Cliradex (Bio-Tissue), an OTC preservative-free lid margin cleanser that uses 4-Terpineol, the key ingredient in tea tree oil.

For an intensive, in-office cleaning, I-Lid ‘N Lash Pro (I-MED Pharma) cleansing gel with 20% tea tree oil is another option.

“In severe cases, we may prescribe an anti-parasite medication such as ivermectin, which can be taken orally,” she says. “In the dermatological world, ivermectin cream is used to decrease the mite load on the face and skin.” Dr. Massaro-Giordano says she typically prescribes oral ivermectin, 18 mg once a week, repeated three weeks later. “A 1% cream on the lids at bedtime helps as well,” she says.

“Allergies too can exacerbate or cause a subtle form of blepharitis that doesn’t receive much attention,” she adds. “I find that allergies and posterior and anterior blepharitis can coexist.”

In addition to mites and allergies, bacteria are another possible culprit. Common ones include Gram positive bacteria or Staphylococcus. “Many types of bacteria live on our lids, and when you have an imbalance of bacteria, the body may react to the proteins and the toxins that some of these bacteria produce,” she says. “We don’t routinely swab or culture the lids, so it’s difficult to tell which bacterium is causing the inflammation. Staphylococcus may coexist with several types of blepharitis, for example, but we’re not usually able to tell if it’s running the blepharitis picture.”

Dr. Amescua adds that children don’t usually complain of the same symptoms of dryness that adults do. “They tend to have a much healthier tear film,” he notes. “However, both may experience itchiness, burning, discomfort or blurring episodes. Oftentimes, children will complain of itchiness, and when the parent notices the eye becoming red, they think it’s just an allergy. It’s often blepharitis secondary to pediatric rosacea.”

Importance of Expression

With so many possible etiologies, there’s no single, set algorithm that doctors follow when diagnosing blepharitis. “Most diagnoses hinge on careful observation and a thorough examination,” says Dr. Massaro-Giordano. “Look for certain pathognomonic signs of blepharitis such as thickening of the lids or telangiectatic blood vessels along the eyelid margins.

“Once the lid is inflamed, that inflammation will spread to the meibomian glands,” she continues. “Look specifically at the orifices of the oil glands and see if they have an odd shape or are scarred down from past inflammation or past styes. Are they thickened? Are there many telangiectatic vessels around the openings? More importantly, what helps me tell the difference is pushing on the eyelid to see what secretions come out. Are they granular, thick or yellow? Or clear with an olive oil-like consistency?

“When the lids become inflamed and irritated, the secretions change—melting points can change,” she says. “Healthy lids usually produce a very fluid, olive oil-like secretion, but an abnormal gland will produce a pasty secretion. It’s very likely that you won’t notice this unless you push on the glands. This helps me tell what degree of posterior blepharitis a patient might have.”

“I teach all my residents and fellows to do a manual expression of the glands during the exam,” says Dr. Amescua, whose patients are first seen by technicians for Schirmer’s and MMP-9 tests. “You can find out a lot about a patient’s condition by expressing the glands. We put in a numbing drop and press the eyelid glands with a Q-tip. If I’m not satisfied with what I find, I may do meibography to help visualize any morphologic changes in the glands.”

One other clue that may indicate posterior blepharitis is saponification of the tear film, which occurs when bacteria living on the lids break down the oils in the tear film. “Look for soap-like deposits in the tear film, suds or foamy tears with debris along the lid margins,” says Dr. Massaro-Giordano. “Some patients will complain of a burning sensation, just as when you get soap in your eyes.”

Patient History

Taking a thorough patient history can also help point you toward a blepharitis diagnosis. Sjogren’s syndrome or a history of dermatologic conditions may dispose a patient to blepharitis.

“It’s also important to ask how patients take care of their faces, in general,” says Dr. Massaro-Giordano. “I ask all patients: Do you clean your eyelids? When you wash your face, do you take the time to clean along the lash line? If they tell me, ‘No, I never touch my eyes when I wash my face,’ that could be a problem.”

Lid scrubs such as Ocusoft Lid Scrub (Ocusoft) and Sterilid (TheraTears) may help patients who shy away from washing near their eyes feel more comfortable with their lid hygiene. The scrubs contain non-irritating cleansers for removing ocular debris, dirt, oil and pollen. Another option for lid and gland hygiene is a hypochlorous acid wash, which kills a broad spectrum of bacteria. Ocusoft’s formulation is 0.02% hypochlorous acid solution; Avenova (Nova Bay Pharmaceuticals) is a 0.01% wash.

Preservatives in glaucoma drops may also be blepharitis culprits. If patients are experiencing significant inflammation of the lids or ocular surface from their glaucoma drops, Dr. Amescua says he discusses the possibility of switching to a preservative-free drop with the patient. Stopping the drops with close follow-up is another option, but he says, “if the glaucoma specialist who referred the patient to me says we can’t do that, then we may put the patient on an oral medication to lower the pressure and wait a few weeks to see how the patient does before reassessing.”

Another clue pointing to blepharitis may be the number of eye-care providers a patient has visited for their dry-eye complaints. “Oftentimes, patients are being treated for dry eye from a symptomatic standpoint but not for the root of the problem,” says Dr. Jeng. “If the blepharitis goes untreated, the patient will continue to have undesirable dryness or dryness symptoms.”

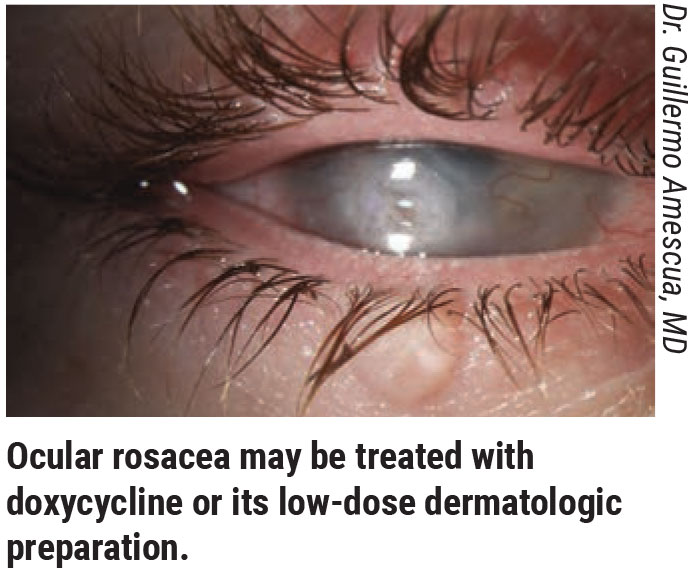

Acne rosacea is another sign to look for, Dr. Jeng notes. “Rosacea blepharitis is a posterior blepharitis in which, just as in rosacea, the blood vessels become dilated, leading to inflammation of the lids. This causes swelling, and the swelling then chokes off the meibomian glands and obstructs the oils from entering the tear film.”

Patient Compliance

The better patients understand both the condition and the necessary treatment, the better their compliance tends to be, experts say.

“When your patient has a significant number of Demodex mites, they’re very easy to treat,” Dr. Amescua says. “Once I identify this possibility, I pull some lashes, look at them under the microscope and show the patient. They become very compliant when they see the little mites walking around. When they come back for follow-up, they’ve almost always improved.

“If a patient has an associated skin condition such as psoriasis, their compliance is also likely to be high since they already understand the problem well and will follow the proper treatment to get better,” he adds.

The more difficult cases of compliance tend to be those involving meibomian gland stasis and dysfunction, Dr. Amescua notes. “Newly referred patients often come to me with a plastic bag of all the drops they’ve been using with no improvement,” he says. “The patients are told to do warm compresses and lid hygiene, but oftentimes they believe the true treatment is the drops. If we could develop a drop that could improve the glands, that would be wonderful, but for now it’s up to us to clearly explain to the patients the benefits of maintaining good lid hygiene and using mechanical or thermal treatments to improve the flow of oil.”

Even if a patient has a significant portion of their meibomian glands intact, Dr. Massaro-Giordano says she encourages patients to take proactive steps to preserve those healthy glands. “It can be challenging for clinicians to explain to patients why they need to be aggressively treating glands that appear normal,” she says. “Even if the patients aren’t bothered and the lid looks normal to me, I’ll tell them to start taking care of their lids—warm compresses, lid scrubs, sometimes a treatment—in order to preserve the integrity and function of the glands. If they don’t, it could pose a problem in the future.”

On the other hand, some patients become overzealous in their lid hygiene. “Excessive scrubbing and heat can really hurt the lid,” Dr. Massaro-Giordano says. “Warm compresses heated too hot in the microwave may damage the skin, and harsh scrubbing may inadvertently scratch the conjunctiva or cornea.”

Indeed, more isn’t always better. “Many times patients will have blepharitis but think it’s allergies and begin inundating their eyes with allergy drops,” she says. “In fact, they’re making it worse by introducing antihistamines and preservatives to the eye that may be drying it out further. Others will use artificial tears excessively, which just creates a further imbalance by washing out integral components of the tear film.

Dr. Amescua says that another downside of overzealous attention to the lids or the mistaken belief that drops are the most important treatment is an unhealthy fixation on the eyes. “Prescribing so many drops for patients tells them to think about their eyes all day—taking this drop, and then this other drop,” he explains. “They spend the whole day putting drops in and thinking about their disease. I don’t think that’s good for them psychologically.”

Treatments

|

“We rely a great deal on patients being conscientious about doing their compresses and lid hygiene,” says Dr. Jeng. “Patients tend to be more compliant with drugs, but the warm compresses and scrubs are very important. I start with warm compresses, oral doxycycline or azithromycin, depending, and I go from there.”

However, Dr. Jeng says he generally doesn’t treat patients for blepharitis unless they’re symptomatic or if he’s trying to optimize their ocular surface before cataract surgery. “If you tell them to start scrubbing their eyelids, there’s a chance they may develop symptoms that make it worse,” he says. “Then you’re up the creek without a paddle because you told them to do it, and now they’re having symptoms.”

In addition to lid scrubs, cleansers and compresses, here are some other treatment options:

• Antibiotics. Dr. Massaro-Giordano prescribes topical azithromycin for a few weeks and has patients massage it around their lash line. She says erythromycin ointment used at night is also effective.

“Doxycycline is used for facial rosacea and can help ocular rosacea as well—not so much for its antibacterial effect but because it helps to stabilize the tear film by altering the lipids produced by the meibomian glands,” says Dr. Massaro-Giordano.

While there’s no set dosage for treating blepharitis with doxycycline, she says that common dosing may include a low dose of 40 mg/day for a few months; 100 mg b.i.d. for one month; or 100 mg daily for two or three months.

Dr. Jeng adds that his doxycycline regimen consists of a tapered dose of 100 mg b.i.d. for the first month, 50 mg b.i.d. for the second month and then 50 mg q.d. “Sometimes I then go to 50 mg every other day,” he says. “I find that patients, especially those with rosacea blepharitis, also do well with the dermatologic preparation. It’s a low-dose doxycycline that’s meant to provide the benefits of the drug’s anti-inflammatory properties without the side effects of doxycycline, like GI upset and sun sensitivity.”

“I try to avoid this antibiotic in the summer because of the increased sun sensitivity side effect,” Dr. Massaro-Giordano says. “It’s best for use in the winter, when dry eye is also more of an issue with indoor heat exposure and low humidity.”

Steroids. Steroids weren’t approved to treat dry eye for many years, but we now know topical steroid drops help to calm lid inflammation. Dr. Massaro-Giordano says she usually uses a short-course combination of tobramycin and dexamethasone, and/or cyclosporine drops for the long term.

In December 2020, a low-dose formulation of loteprednol etabonate, Eysuvis (Kala Pharmaceuticals), ophthalmic suspension 0.25%, was FDA-approved for use in episodic dry eye. “It can be used for two to three weeks at a time, and it’s been shown to be well-tolerated and to produce very few side effects,” says Dr. Massaro-Giordano. “With steroids, we worry about increasing IOP or cataract formation, but this new formulation has a different mechanism of action, which has little effect on IOP.” This corticosteroid is dosed at one to two drops, four times a day up to two weeks.

Dr. Jeng prescribes topical steroids drops for a short course if the lid appears inflamed, but for more serious cases, he says, “I have patients do warm compress first and follow this by putting a drop of steroid on their fingertip and scrub it into the eyelid margin. This increases penetration into the eyelid for a stronger effect than a drop in the eye would yield.”

For this treatment, the steroid and its dosage are stronger than that of a drop meant for conventional instillation, because it’s meant to go on the skin, says Dr. Jeng. “Dexamethasone or prednisolone aren’t substances you’d normally drop into the eye for ocular surface disease because they penetrate so deeply into the eye,” he says. “Normally, you want something that penetrates less into the eye to treat the surface, but for this method, I do want penetration into the eyelid.”

Thermal treatments. Though warm compresses are the mainstay of many blepharitis treatment regimens, they have their limitations. “The warmth lasts only a few minutes and then the water’s cold again,” says Dr. Amescua. “They’re not always the way to go. Luckily, we have many devices such as eye masks available and procedures such as thermal pulsation to open obstructed lid glands.

“A manual expression is part of my standard office protocols, and if patients feel significant improvement, I strongly recommend they then have a treatment with the LipiFlow machine (J&J Vision), which is FDA-approved for treating posterior blepharitis,” he says. “We follow that with a series of manual expressions. I recommend they return periodically for LipiFlow.

“This intervention isn’t a cure, but it’s very helpful,” he notes. “About 80 percent of my patients notice at least an 80-percent improvement. It’s important, however, to inform patients that they shouldn’t expect a 100-percent improvement with these interventions.”

LipiFlow and other thermal treatments and low-light therapy such as LacryStim IPL (Quantel Medical), iLux (Alcon), MiBo Thermoflo (MiBo Medical Group), Epi-C PLUS (Espansione Group), TearCare (Sight Sciences) and eyeXpress (Holbar Medical Products)—some of which are used off-label—are not typically covered by insurance.

The iTear100 (Olympic Ophthalmics), a prescription at-home neurostimulator, was recently FDA-cleared for temporarily increasing tear production. In clinical trials, mean Schirmer index was 9.4 mm (95% confidence interval [CI], 7.4 to 11.3) and baseline OSDI improved by an average of 14.4 (95% CI, 11.1 to 17.7) at 30 days. Both of these endpoints were statistically significant.1

Probing of the lid. Another procedure for obstructed glands involves probing the eyelid. “If some of the meibomian glands are scarred over or if there are fibrous bands of tissue over the gland orifices, you can use a specialized probe to poke through the obstruction, which allows the meibum to be released more readily,” says Dr. Massaro-Giordano. “This method was introduced by Steven Maskin, MD, in 2010 and is performed at the slit lamp with a blunt stainless steel 76 µm-diameter probe. After applying an anesthetic agent to the lids, the probe is gently introduced into the orifice, taking care not to create false passages. It’s well-tolerated by patients and can offer relief from these obstructed glands.”

Manual cleaning. “Mechanical debridement or microblepharoexfoliation of the lids can also be helpful to treat blepharitis,” says Dr. Massaro-Giordano. The BlephEx (BlephEx) device, which uses a specialized brush to exfoliate the lash line and clean away biofilm and bacteria, is one option. Dr. Amescua says it pairs well with Lipiflow. “It’s good for patients with significant debris on the lashes, Demodex or sebhorreic blepharitis,” he says.

The at-home hygiene device NuLids (NuSight Medical) is intended to stimulate the glands and clean away debris with an oscillating brush head. The company says it includes a safety mechanism to protect the cornea that stops the brush head if too much pressure is applied.

“There are widely differing views on these technologies,” says Dr. Jeng. “In theory, mechanical warming and massaging to clear the glands or in-office cleaning probably does have some benefit, but do I think it’s absolutely necessary? I haven’t found I’ve had to rely on these machines. The mild to moderate cases don’t necessarily need this equipment, though the patients with more severe symptoms may benefit from it. I’ve had many patients tell me that they work well, and if they want to try it that’s fine with me.”

In some cases, a patient’s symptoms don’t improve, even though the patient appears significantly better on clinical exam. “In these cases, we may not be dealing with significant blepharitis or dry-eye disease, but something that we’ve become more aware of in the past five years: chronic ocular pain syndrome,” Dr. Amescua says. “Pain becomes centralized, so we can’t treat it with drops—they won’t work. With the support of Anat Galor, MD, we’ve started an ocular pain syndrome program in collaboration with a headache and facial pain specialist that significantly helps these patients.”

“Ocular pain syndrome consists of dysregulation of the nerves serving the ocular surface,” Dr. Jeng says. “You can differentiate ocular pain syndrome from dry-eye-related pain by instilling a drop of anesthetic in the office. If the discomfort goes away, it’s probably dry eye. If it goes away only partially or not at all, then it’s time to seriously consider ocular pain syndrome. Because the pain is centrally mediated, we treat it with systemic medications such as gabapentin or pregabalin, or with antidepressants that have an effect on the nerves. However, it’s not totally understood now. Once we have a better understanding of its relationship to dry eye and blepharitis, I believe that will help us target therapies better.”

The Future of Blepharitis Treatment

Dr. Massaro-Giordano says that the future of blepharitis treatment likely lies in combination therapy. “Evaluation of genetics and targeted therapies are in the pipeline for patients with blepharitis,” she says.

Lately, there’s been increased interest in blepharitis and its implications for the ocular surface, says Dr. Jeng. “Many researchers are currently focused on posterior blepharitis and the resulting dry eye for preoperative ocular surface treatment. It’s become pretty standard to preemptively treat blepharitis now to get the best possible outcomes after cataract surgery.”

Dr. Amescua notes that a deeper understanding of why the meibomian glands become inflamed and how the oil becomes static will help develop more treatments. “I think in the future we’ll see more devices that are safe, effective and affordable for at-home improvement of meibomian gland function,” he adds.

Strategies for Success

Here are some pearls for blepharitis management:

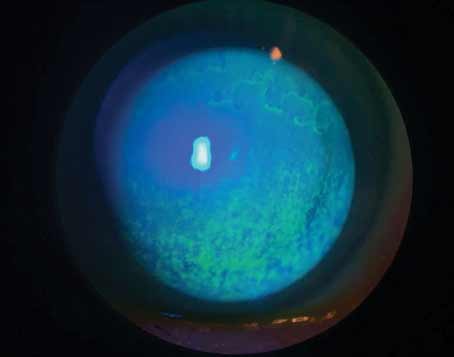

• A good clinical exam is sufficient to make a diagnosis. “You don’t need fancy equipment to diagnose blepharitis,” says Dr. Amescua. “A good clinical history and exam, which might include fluorescein or Lissamine green, questionnaires and manual gland expression are sufficient. If you have access to other equipment such as meibography, that’s helpful, but not necessary.”

• Treat the root of the problem. “This pearl is fairly obvious, but it’s important to keep in mind,” says Dr. Jeng. “Treat the blepharitis—not just the dry eye.”

• Emphasize to the patient the importance of warm compresses and lid hygiene. “Patients are likely to believe that drops are the most important aspect of the treatment, but if they don’t have a tear deficiency and still experience dry eye, their glands are the problem, and they won’t improve with drops,” says Dr. Amescua.

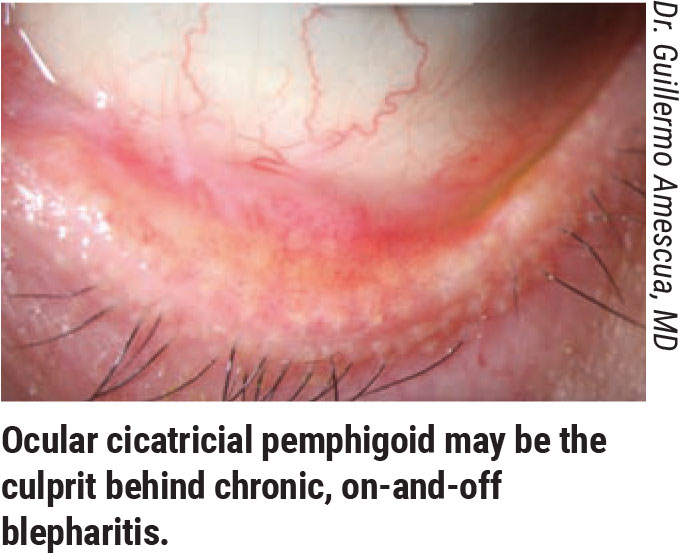

• Chronic on-and-off blepharitis episodes may point to an autoimmune condition. Dr. Amescua says, “If you’re dealing with a chronic dry-eye patient who’s been treated for meibomian gland disease that waxes and wanes or a patient who was on topical steroids and improved but stopped due to risk of cataract or glaucoma, it’s important to flip up and examine the eyelids to look at the conjunctiva and ensure there’s no signs of scarring, shortening of the fornix or symblepharon. One of the most common scenarios in our clinical practice is when patients with many months or years of chronic on-and-off red eye due to blepharitis end up having an autoimmune condition such as ocular cicatricial pemphigoid.”

• Don’t miss blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in children. “Blepharitis in children is unusual, so if you see it, don’t dismiss it,” says Dr. Jeng. “Specifically, blepharokeratoconjunctivitis is something to maintain suspicion for. It’s often asymmetric and very aggressive, and it causes serious ocular surface problems, such as corneal infections and vision loss. You have to treat this disease very aggressively: topical steroids are one option, but the mainstay is oral antibiotics—usually erythromycin. Because the disease affects young children, you don’t want to use tetracycline. The erythromycin’s anti-inflammatory properties keep things under control. Children as young as age three may develop blepharokeratoconjunctivitis, but it tends to burn itself out by the late teen years.”

• Maintain suspicion for tumors in older patients. “In older individuals, if you see blepharitis that looks a little strange—eyelash loss, for example—make sure to think about tumors, specifically sebaceous cell carcinoma,” warns Dr. Jeng.

Some of the telltale signs are localized swollen areas, missing eyelashes, an ulcerative appearance or a pearly border, says Dr. Massaro-Giordano. “If you have a lesion that’s refractory to the typical blepharitis treatments—warm compresses, scrubs, a short course of steroids—or it gets worse, that should raise a red flag,” she says. “It may indicate something more serious or malignant that should be biopsied.”

Drs. Massaro-Giordano, Jeng and Amescua have no relevant financial disclosures.

1. Ji MH, Moshfeghi DM, Periman L, et al. Novel extranasal tear stimulation: Pivotal study results. Trans Vis Sci Tech 2020;9:12:23.