Just because we see something every day in our offices, doesn’t make it any less confounding. Blepharitis is a good example: It’s not rare by any means, but it remains a challenge to successfully diagnose and treat, since the overlap of symptoms and signs and the association with dermatologic conditions including rosacea, seborrheic dermatitis, and eczema can lead to misdiagnosis, underreporting of the condition and variable management protocols with variable outcomes. Here, I’ll review how I approach this condition, and share pearls for managing it.

The Condition

Also in this Issue... Artificial Intelligence for the Cornea Specialist by Christine Yue Leonard DSO and Cultured Endothelial Cell Transplants: A Review by Thomas John, MD, and Anny M.S. Cheng, MD Premium IOLs in Patients with Corneal Conditions by Asim Piracha, MD |

Blepharitis is a common, chronic ophthalmologic condition characterized by inflammation of the eyelid margins associated with recurrent symptoms of eye redness, tearing and irritation. It occurs in people of all ages, ethnicities and in either sex.

The etiology of this complex disease includes infectious (bacterial; viral herpes simplex, zoster, molluscum), immune (atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, mucus membrane pemphigoid, Stevens-Johnson Syndrome), dermatologic (rosacea, psoriasis) traumatic (chemical and thermal) and neoplastic including benign (papilloma, actinic keratosis) and malignant (sebaceous cell, melanoma, squamous cell, basal cell) eyelid tumors.

Ulcerative forms are usually infections, like herpes simplex or zoster, while inflammatory disease is usually non-ulcerative.

Blepharitis may differ based on the location of eyelid inflammation (posterior versus anterior). Demodex blepharitis is frequently overlooked in the assessment of blepharitis in part because Demodex can also be asymptomatic. Other skin conditions like rosacea may also be associated with posterior blepharitis and meibomian gland dysfunction. Like most ocular diseases, careful consideration must also be given to normal age-related changes that occur in the eyelid and ocular surface.

According to a 2009 survey, the prevalence of blepharitis in the United States probably lies between 37 percent, reported by ophthalmologists, and 47 percent, as reported by optometrists.1 Associated dry-eye disease (DED) is present in 5 to 30 percent of patients over age 50 with MGD as one of the leading causes of evaporative DED (EDED).2,3 MGD is responsible for 66 to 78 percent of DED making it a clinically significant condition.4

There have been many proposed classification systems for blepharitis. The most recent system comes from the International Workshop on MGD: In the report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee, the term blepharitis refers to inflammation of the eyelid as a whole whereas marginal blepharitis refers to inflammation of the lid margin and includes anterior and posterior blepharitis (discussed in more detail under “Clinical Evaluation,” below).5

What Causes It

Figure 1. A Systematic Approach to the Potential Blepharitis Patient 1. Patient History 2. Symptom Questionnaire (OSDI, DEQ-5, SPEED, NEI-VFQ25) 3. External Examination (rosacea, seborrhea, blink pattern) 4. Tear Osmolarity (if available) 5. Meibography and Lipid Layer Thickness (LLT) (if available) 6. Corneal Sensation (Luneau Cochet-Bonnet aesthesiometer) 7. Anterior Eye Assessment (Slit Lamp Exam) a. Meibomian Gland Assessment (volume, thickness, plugging) b. Corneal Integrity Assessment (fluorescein) c. Conjunctival Integrity (Lissamine Green) 8. Tear Film Assessment a. Tear-film Breakup Time (TFBUT) b. Tear Volume Assessment (Schirmer I) c. Inflammatory Mediators (InflammaDry) 9. Additional Testing a. Demodex b. Cultures c. Biopsy (neoplasia) |

Blepharitis is multifactorial, involving the eyelid margin, meibomian glands, bulbar and tarsal conjunctiva, cornea and the lacrimal gland. These structures all contribute to the normal homeostatic state of the ocular surface and normal tear film. With the presence of disease, the integrity of the ocular surface is disrupted, leading to a cycle of eyelid and ocular surface disease that’s often difficult to break. Altered lipid composition of the meibomian gland secretions can lead to instability of the tear film. These abnormal secretions can have a direct toxic effect on the ocular surface.6 Additionally, because the microbiota of the tear film is dependent upon proper meibomian gland function, a proliferation of pathogenic microbes may take place, including the proliferation of Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Corynebacterium and Cutibacterium species.

Blepharitis can also result from activity of the mite Demodex folliculorum, a parasite that has been identified in 30 percent of patients with chronic anterior blepharitis affecting the base of the lashes, but which is also found with approximately the same prevalence in asymptomatic people. It’s present in more than 75 percent of adults over 70, and it’s clearly a contributing factor in some patients as evidenced by the symptomatic improvement seen in the response to therapy.

In a 2018 study, with 500 patients, Demodex was identified in almost 80 percent of blepharitis patients but also in 31 percent of controls.7 The researchers found Demodex in 40 percent of 229 patients with dry-eye symptoms.8

The prevalence of Demodex also increases with age (with or without the associated diagnosis of blepharitis) and so should be ever present in the differential diagnosis of patients with chronic ocular surface disease.9,10

A second species, Demodex brevis, has been associated with posterior blepharitis and occupies the meibomian glands.11 The altered tear-film integrity and the proliferation of these organisms lead to a generalized inflammation of the ocular surface. Long-term inflammation leads to gland dysfunction, hyper-keratinization and fibrosis, as well as damage to the eyelid and ocular surface.

Hyper-keratinization, therefore, is an early finding in patients with posterior blepharitis and diagnosing and grading this change is critical to staging the severity of the disease. These changes result in worsening meibomian gland function, perpetuating the cycle.

Underlying inflammatory skin conditions such as rosacea and seborrheic dermatitis may also be associated with posterior blepharitis, although these conditions commonly occur in their absence. Blepharitis in patients with underlying chronic dermatoses tends to be more severe.

Chronic infection may also play a role in posterior blepharitis, although this manifestation has been studied less than in anterior blepharitis. The bacteria that comprise the lid and conjunctival flora in posterior blepharitis are the same as those on normal skin but are present in greater numbers.12 They include coagulase-negative staphylococci, Corynebacterium species, and Cutibacterium acnes. D. brevis should also be included in the etiology of posterior blepharitis. Bacterial lipase produced by colonizing bacteria on the ocular surface may contribute to the differences in lipid composition in the tear film in patients with blepharitis.

Other possible causes of blepharitis include contact (allergic) dermatitis, eczema and psoriasis. Contact allergic blepharitis is an acute inflammatory reaction of the skin of the eyelids, usually occurring as a reaction to an inciting agent found in some cosmetics.

Clinical Evaluation

|

|

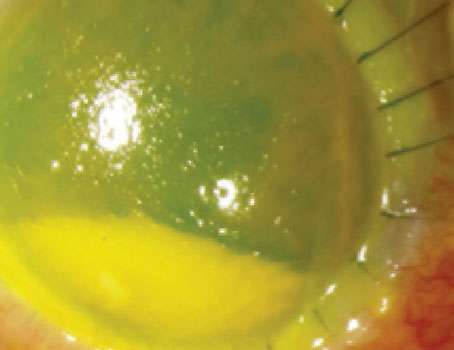

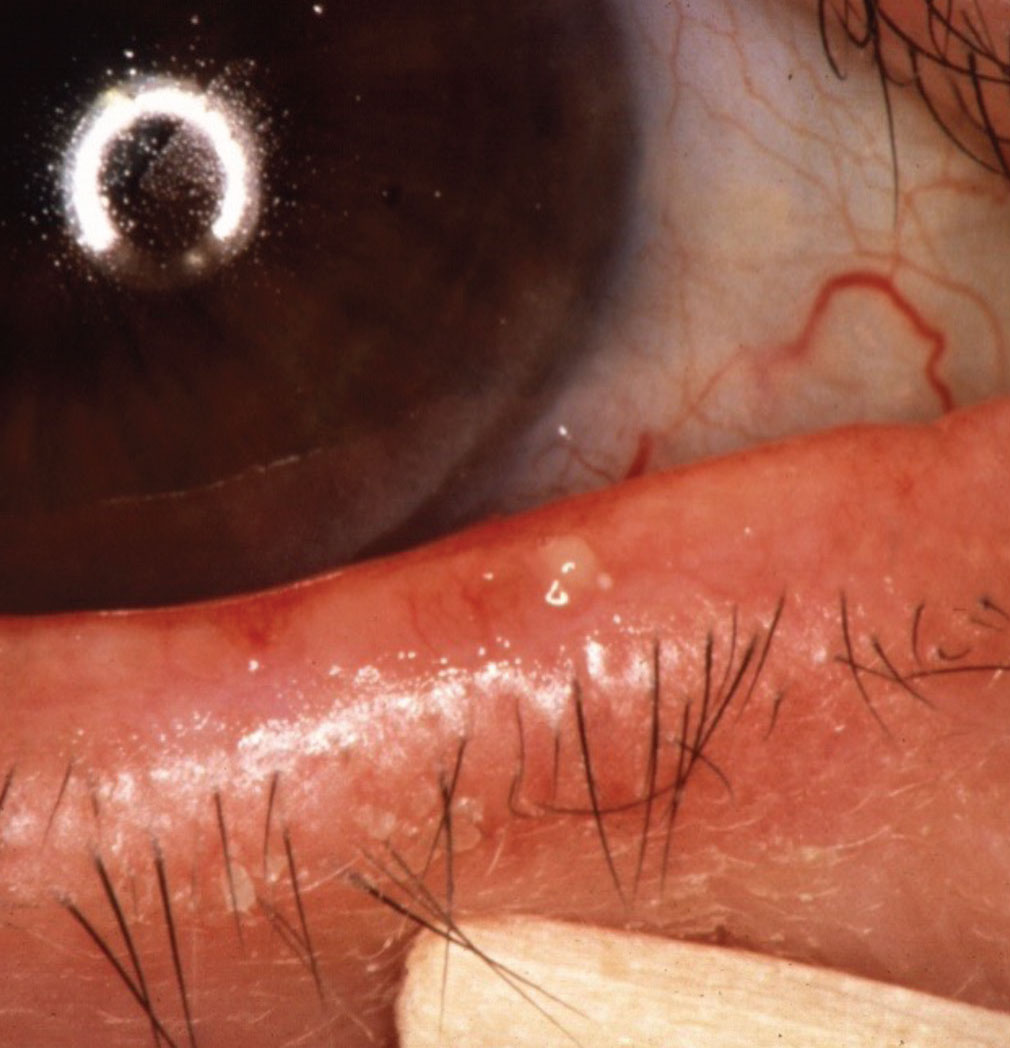

Rosacea with MGD. Shown is a blocked meibomian gland undergoing gentle expression. |

Your diagnosis and evaluation of blepharitis should consist of a comprehensive multi-step process that involves both subjective and objective measures (See Figure 1). Many cases of chronic blepharitis are associated with evaporative dry-eye disease and meibomian gland dysfunction, and so are a part of a broader category of ocular surface disease. More severe and chronic eyelid disease can also be a risk factor for sight-threatening corneal inflammatory disease.

When a patient presents in your office with possible signs of blepharitis, here’s how to home in on the right diagnosis:

• Symptoms. Patients with blepharitis typically complain of irritation, redness, burning, crusting, sticking eyelids and sometimes tearing. They may also complain of blurred vision that improves with blinking and some photophobia. The symptoms are usually chronic, and wax and wane over time; they’re often worse in the morning upon awakening.

• Dermatologic evaluation. Facial rosacea should always be assessed, since about a quarter of patients with blepharitis also suffer from rosacea. Telangiectasias, papules and pustules of the face, glabellar and chin regions are typical signs, along with prominent sebaceous glands. I always look for signs of rosacea in every patient who complains of ocular irritation.

• Anterior blepharitis. Anterior blepharitis refers to eyelid inflammation anterior to the gray line and is associated with eyelash inflammation often connected to squamous debris and collarettes. Anterior blepharitis is less common than posterior blepharitis and is characterized by inflammation at the base of the eyelashes. Patients with anterior blepharitis are often female and tend to be younger than those with posterior blepharitis.

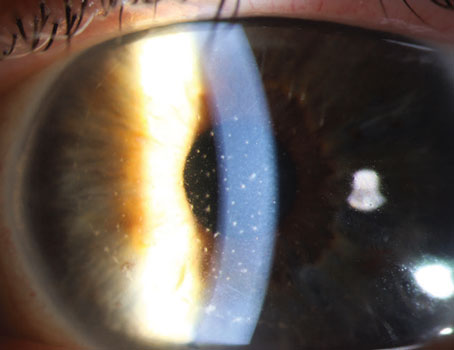

Anterior blepharitis can be further separated into staphylococcal or seborrheic types, although Demodex folliculorum has also been implicated.13 Staphylococcal blepharitis is characterized by lid margin erythema, mild edema, inflammation, telangiectasias, scaling of the skin and loss of lashes (madarosis). Whitening (poliosis) and lash misdirection can also occur. Characteristic scaling that results in the formation of “collarettes” around the bases of the lashes may be present. (These differ from the more tightly bound “sleeves” characteristic of Demodex folliculorum.) The fibrinous scales and crusts around the eyelashes are caused by colonization by Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci. In addition, Staphylococci may alter meibomian gland secretion and cause blepharitis via various mechanisms, including direct infection of the lids, production of staphylococcal exotoxin, and by provoking an allergic reaction. It’s likely that a combination of these factors is responsible for the manifestations of anterior blepharitis.

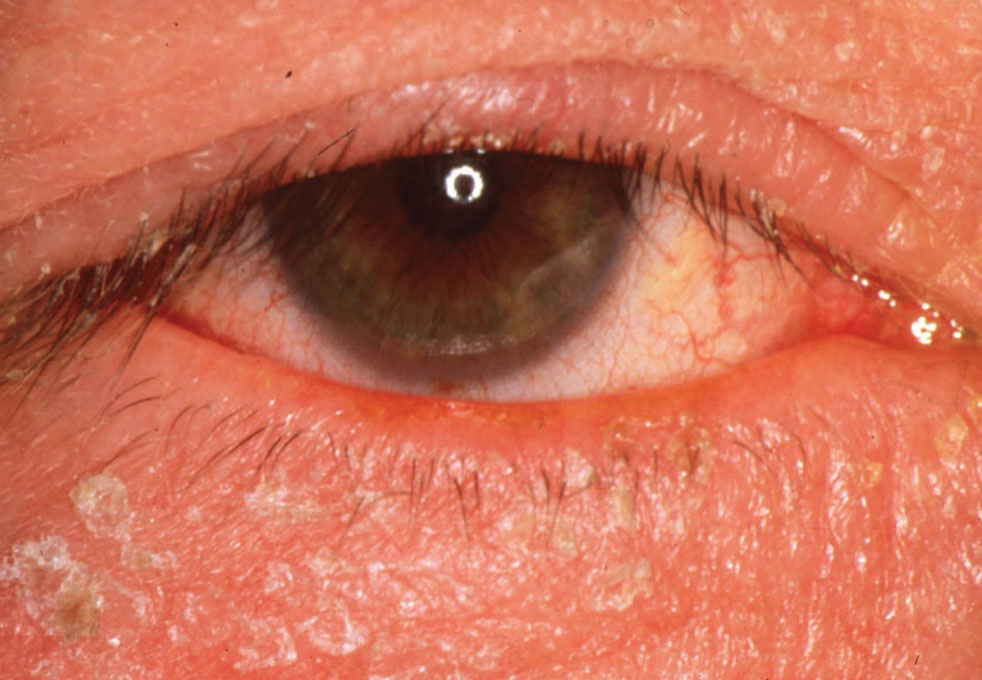

The seborrheic type is characterized by dandruff-like skin changes and greasy scales around the base of the eyelids associated with the sebaceous glands of Zeiss. The oily scale and crusting can also be found on the retroauricular, glabellar and nasolabial fold areas as well.

|

|

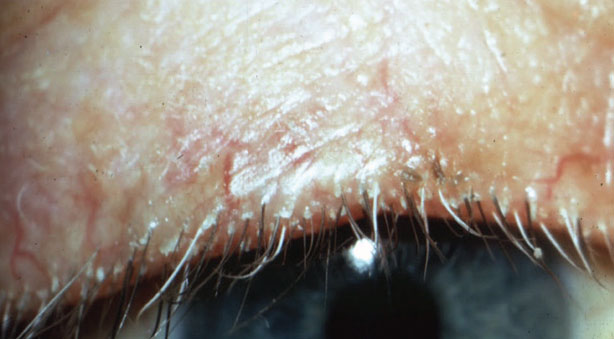

Demodex with typical cylindrical sleeves on lashes. Here, lashes were pulled and examined. |

• Demodex. The diagnosis of Demodex blepharitis can be made from clinical evaluation as well as epilating suspicious lashes, placing the eyelashes on a glass slide and then examining the organism under a cover slip after a drop of fluorescein has been added.

The definitive diagnosis can also be made through confocal microscopy.14,15 Epilation of the eyelashes for microscopic examination to detect Demodex mites is warranted when the clinical presentation (e.g., presence of cylindrical dandruff or “sleeves” on the eyelashes) is suggestive of this diagnosis, or when there’s severe or refractory blepharitis.

• Posterior blepharitis. Posterior blepharitis refers to inflammation associated with the posterior lid margin, meibomian gland dysfunction, conjunctival inflammation and other causes, including D. brevis.11

By way of quick review, MGD is a chronic, diffuse inflammation of the meibomian glands commonly associated with terminal duct obstruction and/or abnormalities of the secreted meibum. The new classification system proposed by the International Workshop on MGD differentiates the various MGD subgroups on the basis of the level of secretion, with obstructive MGD being the most common type.5

In the clinic, posterior blepharitis patients will have dilated or obstructed meibomian glands, with thickened turbid secretions associated with telangiectatic vessels and lid margin scarring in severe cases.

• Carcinomas and other serious conditions. Critically important is the careful assessment of the eyelids and ocular surface for potentially severe sight- and life-threatening diseases, including basal cell carcinoma and sebaceous cell carcinoma. You should have a strong index of suspicion if the patient has a history of chronic eyelid inflammation that’s been unresponsive to aggressive treatment, including corticosteroids.

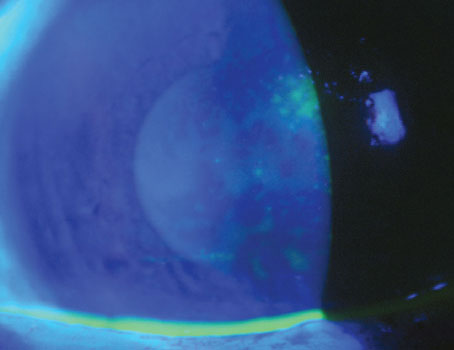

Severe corneal complications can also develop with rosacea blepharokeratoconjunctivitis including punctate epitheliopathy, corneal neovascularization, infectious keratitis and thinning—even perforation. These patients should be referred early to a cornea specialist.

Diagnostic Testing

In addition to your exam and patient history, certain diagnostic tests can help you zero in on the problem. The complete list of our diagnostic process (including history, etc.) appears in Figure 1. The recommended list of a standardized sequence of ocular surface clinical and diagnostic assessments should provide valuable diagnostic, quantitative information to properly assess blepharitis and meibomian gland-related ocular surface disease. Here, however, we’ll expand on a couple of the tests to explain what we’re looking for:

• Tear osmolarity. It’s generally accepted that a tear osmolarity measurement greater than 308 mOsm/mL is abnormal, as well as a difference between the eyes of 8 mOsm/mL. We don’t rely on this too heavily, but it’s an important theoretical factor, because when the quality of tears is abnormal, the hyperosmolarity that results provides an insult to the surface, leading to low-grade inflammation.

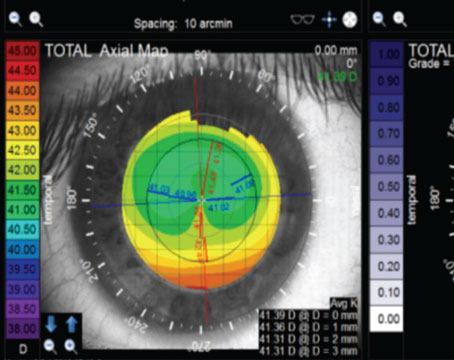

• Meibography and lipid layer thickness (if available). The Heiko Pult Meiboscale provides a good visual grading system of Meibomian Gland Dropout that helps patients understand the condition better (https://www.heiko-pult.de/media/files/MEIBOSCALE-2016--Einseiter-ADD-Sec.pdf). The LipiView device also provides a quantitative measure of the lipid layer thickness (LLT), with normal being over 65 µm. Both these values help in assessing the presence and severity of the MGD.

• Blink rate/staining. It can be very useful to observe the patient’s blink rate. The LipiView device will also document incomplete blinks, though I’m not entirely sure of its reliability for diagnosis. However, you can use the results from a device such as the LipiView to show patients that they’re not closing their eyes completely when they blink. In these patients, most (but not all) will also have inferior punctate staining. Importantly, if you lift the upper lid and there isn’t superior punctate corneal staining, that’s a good sign. If there’s staining under the upper lid in these patients, however, that would suggest a toxic etiology, and you may want to look at other drops they’re taking, such as those for glaucoma.

• Corneal sensation. As a follow-up to the previous point about blinking, if a patient blinks a lot that’s often a good sign that their corneal sensation is normal. If someone doesn’t blink a lot, be sure to do a test of corneal sensation, since it may be abnormal. Normal sensation is critical for normal epithelial healing.

• Tear-film breakup time. This is the most important diagnostic tool for the diagnosis of tear dysfunction syndrome (TDS), and is probably more important than Schirmer test and punctate staining. It’s critical that this measurement be carefully performed and documented.

Treatment

Once you’ve settled on a diagnosis, you can embark on the path to treatment. Following are the best routes to take for the various causes of the patient’s problem:

|

|

Seborrheic dermatitis with blepharitis. |

• Chronic blepharitis. For chronic blepharitis, many important interventions often have only marginal effects, and for this reason I always try to set realistic expectations regarding the outcome of the treatments (See our practice’s handout on Tear Dysfunction Syndrome, available with the online version of this article on reviewofophthalmology.com). I tell patients that they have to decide whether the various treatments help or not and that we’ll need to try to establish the most effective dose/regimen.

Understanding the chronic nature of the disease is critical to the management. Since the incidence of depression and anxiety in patients with chronic eye disease is high, some patients will fixate on their eye problem until it feels overwhelming. It’s important to explain to patients that you’re not going to solve the problem and make it go away—it’s chronic. In fact, a Cochrane Database Systematic Review of 34 interventions failed to demonstrate a cure of blepharitis, so it’s important to communicate to patients that this will be a chronic and recurrent condition.16 I tell them our job is to figure out which treatments will make their eyes feel a little better—emphasis on “a little.” They must have a mindset that we’re going to try these treatments in an effort to get some marginal improvement.

Although there have been many published reports on the benefits of a variety of interventions, lid hygiene, including lid scrubs and warm compresses remain the mainstay of treatment for this chronic condition (e.g., Ocusoft Lid Scrub, Sterilid, Cliradex, I-Lid ‘N Lash Pro and the TheraPearl Eye Mask). The duration of the heat should be emphasized, as well as the chronic nature of the condition, both of which necessitate regular/daily/weekly management schedules. Remind them that the shampoo should be diluted and be sure to demonstrate the specific gentle meibomian gland massage technique.

For uncontrolled meibomian gland dysfunction, oral antibiotics, including tetracyclines, are recommended.

Newer treatments for managing chronic blepharitis include mechanical devices including Thermal pulsation (LipiFlow, Systane iLux2, TearCare, MiBo Thermoflo), intense-pulsed light (Lacrystim IPL, OptiLight, Epi-C Plus), and microblepharoexfoliation (MBE) devices that mechanically scrub the eyelids, eyelashes, and skin with a gentle mechanical brushing system (NuLids, BlephEx) which remove scales and potentially blocked meibomian gland orifices. Finally, meibomian gland probing has been reported to be effective in some cases especially for the more severe disease (e.g., Stevens-Johnson Syndrome). Topical steroids should also be an option for more severe disease.

Topical preservative-free lubricants can also be useful for those patients with a component of aqueous tear deficiency. Start with aggressive lubricant treatment (q.i.d.) in the beginning and then taper it to the most effective dose that requires the least amount of lubricant.

Oral Omega-3 fatty acids are another theoretically effective approach to the management of posterior blepharitis and MGD. However, the 2018 Dry Eye Assessment and Management (DREAM) study, a prospective, randomized study that analyzed the role of 3,000 mg of n-3 fatty acids/day for 12 months, failed to demonstrate a statistically beneficial effect over the placebo group.17

• Acute cases. For acute infectious disease, topical antibiotic drops and ointment at bedtime (erythromycin or bacitracin) can be effective. Systemic antibiotics are occasionally indicated for their anti-inflammatory, antibiotic and oil gland composition-altering effects. Topical corticosteroids (such as Klarity-L, Lotemax, Inveltys and Eysuvis) or combination steroid/antibiotic drops can also be very effective to control acute inflammation, with the cautionary discussion with the patient of potential for elevating their intraocular pressure with chronic use.

• Demodex blepharitis. For Demodex infection, the critical clinical feature is the cylindrical sleeves at the base of the eyelashes, which is found in 50 to 90 percent of Demodex patients.18 Management with tea tree oil, with its active component terpinen-4-ol, has demonstrated good outcomes in eradicating the organism and reducing the inflammation, as demonstrated in a 2020 meta-analysis.19 It’s important to impress on the patient that treatment must be maintained for six to eight weeks.

Other current treatments including ivermectin, metronidazole, selenium sulfide, as well as conventional lid hygiene.11

Waiting in the wings for Demodex treatment is Tarsus’ anti-parasitic drug TP-03. It’s due to finish Phase III trials this year, and the company may submit its New Device Application to the FDA shortly afterward.

Pearls

After having seen many patients with blepharitis and TDS over the years, I’ve developed certain strategies and approaches that work, such as the following:

• Show them images. Something I’ve found helpful is to have a number of laminated images depicting varying degrees of severity of a variety of anterior segment diseases, e.g., the Meiboscale to demonstrate the different grading levels of meibomian gland loss right there in the clinic. I can show patients the photos and identify their personal level of loss and they get the idea immediately—they love it.

I also show them a standard grading system for Demodex (mild, moderate and severe) and where they land on it. They learn their lid anatomy and can then look in the mirror and see their own condition reflected in the images. Similarly, I have images depicting conjunctival injection and various levels of lipid layer thickness.

Along with these images of disease signs, I also have cards illustrating symptoms. They see the images and they can relate to questions such as: Is it burning like soap in your eye? Is it scratching like sand in your eye? Is it itching like a mosquito bite? Is it a tearing problem?

• “Telephone” diagnosis. You’d be surprised how much you can learn just by listening to a patient’s chief complaint and history of the present illness, even if they’re not in front of you for an exam. I often tell residents this is like being able to do a “telephone” diagnosis in which you can rule out certain diseases and triangulate the problem just by obtaining a detailed and focused history. For instance, knowing how long the condition’s been bothering the patient (years, months, days, hours), whether it’s one eye or both eyes that are affected or if the redness in the eye is diffuse or sectoral can eliminate some diagnoses. I also ask which treatments have been helpful and which ones haven’t worked. I press them to admit whether they actually helped, even a little bit for a short period of time. Response to therapy provides important information to help isolate the diagnosis.

• Treat monocularly first. As a kind of corollary to the previous point, I always begin treatment in one eye first. Why? Because, as mentioned, this patient population can be fixated on their eye problem and be depressed and anxious. They need to see and feel improvement. If you start treatment in both eyes and there is actually some improvement, it’ll be difficult for them to remember how their eyes felt weeks ago and notice the difference now. If you just treat one eye, though, and leave the other eye untreated, they’ll definitely notice the difference between their eyes.

• The sunburn analogy. I also try to impart upon patients the idea that their problem is chronic and it will never completely resolve. As such, prophylactic treatment is key. Just like putting sunblock on after you’ve gotten a sunburn won’t work, it’s harder to make your eyes better if you wait for the irritation to use a drop or treatment. They’ve got to manage their lids and ocular surface constantly in order to prevent and/or reduce the irritation.

In summary, blepharitis is a common, chronic, ocular surface disease with multiple etiologies and complex pathophysiology than can be effectively managed through an interprofessional team of technicians, optometrists and ophthalmologists, supported by a thoughtful patient education program. Regular and careful eyelid hygiene is the most important chronic therapy, with topical antibiotic and immunosuppressive agents are used for acute exacerbations. Demodex is an important diagnostic challenge and, now that we’re armed with a higher index of suspicion for it, should be better managed in the future. Always rule out more serious eyelid disease including sebaceous cell and squamous cell carcinoma for those more severe and usually chronic conditions that are unresponsive to conventional therapy. I hope the techniques and pearls I’ve shared can help you more accurately diagnose and effectively treat your blepharitis patients.

Dr. Bouchard is the John P. Mulcahy Professor of Ophthalmology and Chair of the Department Ophthalmology at Loyola University in Chicago. He has no financial interest in any of the products mentioned.

1. Lemp MA, Nichols KK. Blepharitis in the United States 2009: A survey-based perspective on prevalence and treatment. Ocular Surface 2009;7(Suppl 2):S1–14.

2. Putnam CM. Diagnosis and management of blepharitis: an optometrist’s perspective. Clin Optom (Auckl) 2016;8:71-8.

3. Chalmers RL, Begley CG, Caffery B. Validation of the 5-Item Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ-5): Discrimination across self-assessed severity and aqueous tear deficient dry eye diagnoses. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2010;33:2:55-60.

4. Schaumberg DA, Nichols JJ, Papas EB, Tong L, Uchino M, Nichols KK. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: Report of the subcommittee on the epidemiology of, and associated risk factors for, MGD. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:4:1994-2005.

5. Nelson JD, Shimazaki J, Benitez-del-Castillo JM, Craig JP, McCulley JP, Den S, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: Report of the definition and classification subcommittee. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:4:1930-7.

6. Mizoguchi S, Iwanishi H, Arita R, Shirai K, Sumioka T, Kokado M, et al. Ocular surface inflammation impairs structure and function of meibomian gland. Exp Eye Res 2017;163:78-84.

7. Zeytun E, Karakurt Y. Prevalence and load of Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis (Acari: Demodicidae) in patients with chronic Blepharitis in the province of Erzincan, Turkey. J Med Entomol 2019;56:2–9.

8. Rabensteiner DF, Aminfar H, Boldin I, et al. Demodex mite infestation and its associations with tear film and ocular surface parameters in patients with ocular discomfort. Am J Ophthalmol 2019;204:7–12.

9. Zeytun E, Ölmez H. Demodex (Acari: Demodicidae) infestation in patients with KOAH, and the association with immunosuppression. Erzincan Univ J Sci Technology 2017;10:220–231.

10. López-Ponce D, Zuazo F, Cartes C, et al. High prevalence of Demodex spp. infestation among patients with posterior blepharitis: Correlation with age and cylindrical dandruff. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol 2017;92: 412–418.

11. Shah PP, Stein RL and Perry HD. Update on the management and treatment of Demodex blepharitis. Cornea 2022 Aug 1;41:8:934-939. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002911.

12. Zhang X, M VJ, Qu Y, He X, Ou S, Bu J, et al. Dry eye management: Targeting the ocular surface microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci 2017;18:7.

13. Gilbard JP. Dry eye, blepharitis and chronic eye irritation: Divide and conquer. J Ophthalmic Nurs Technol 1999;18:3:109-15.

14. Luo X, Li J, Chen C, et al. Ocular demodicosis as a potential cause of ocular surface inflammation. Cornea 2017;36(suppl 1):S9–s14.

15. Randon M, Liang H, El Hamdaoui M, et al. In vivo confocal microscopy as a novel and reliable tool for the diagnosis of Demodex eyelid infestation. Br J Ophthalmol 2015;99:336–341.

16. Lindsley K, Matsumura S, Hatef E, Akpek EK. Interventions for chronic blepharitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;5:CD005556

17. Asbell PA, et al. DRy Eye Assessment and Management Study Research Group. n-3 Fatty acid supplementation for the treatment of dry eye disease. N Engl J Med 2018;378:18:1681-1690.

18. Gao YY, Di Pascuale MA, Li W, et al. High prevalence of Demodex in eyelashes with cylindrical dandruff. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005;46:3089–3094.

19. Lam NSK, Long XX, Li X, Yang L, Griffin RC, Doery JC. Comparison of the efficacy of tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) oil with other current pharmacological management in human demodicosis: A systematic review. Parasitology 2020;147:14:1587-1613.

|