Over the course of the last decade or so, considerable investments have been made on the topic of ocular surface disease. More than just “dry eye,” ocular surface disease has proven to be a multi-faceted issue that plays a significant role in people’s well-being. Studies have shown the prevalence of ocular surface disease is higher than previously thought—likely between 5 to 15 percent of the U.S. population1—meaning cataract and refractive surgeons in particular should be on high alert for ocular surface disease in their patients already in an effort to optimize surgical outcomes.

Read on to learn more about how to screen for, diagnose and treat ocular surface disease before proceeding with cataract or refractive surgery.

The Scope of the Problem

Ocular surface disease and dry eye became even more evident during the pandemic, where many people were sheltering remotely or working from home and screen time greatly increased, even among younger patients, says Terrence P. O’Brien, MD, a professor of ophthalmology at the University of Miami. “Evaporative dry eye was being seen even in people in their 20s as opposed to just in the typical older patients,” he says. “Screen time on various devices and evaporative loss of tears is making the curves shift downward to even younger patients in whom we hadn’t really been screening for dry-eye disease or ocular surface disease.

“One unique pre-selection factor in patients seeking refractive surgery is often contact lens intolerance, where they’d been wearing contacts successfully and then, because of ocular surface disease or dry-eye disease, their contact lens wearing time was reduced and comfort levels declined,” Dr. O’Brien continues. “Thus, they’re essentially pre-selected because they’re coming in seeking refractive surgery due to the discomfort of wearing their contact lenses. That’s a very well-understood reason for many patients to seek refractive surgery. We have to identify that and treat the dry eye or ocular surface disease that led to contact lens discomfort prior to even considering refractive surgery.”

|

|

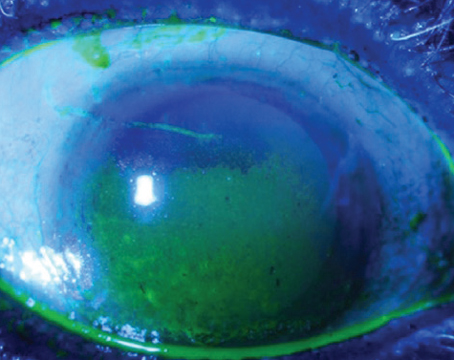

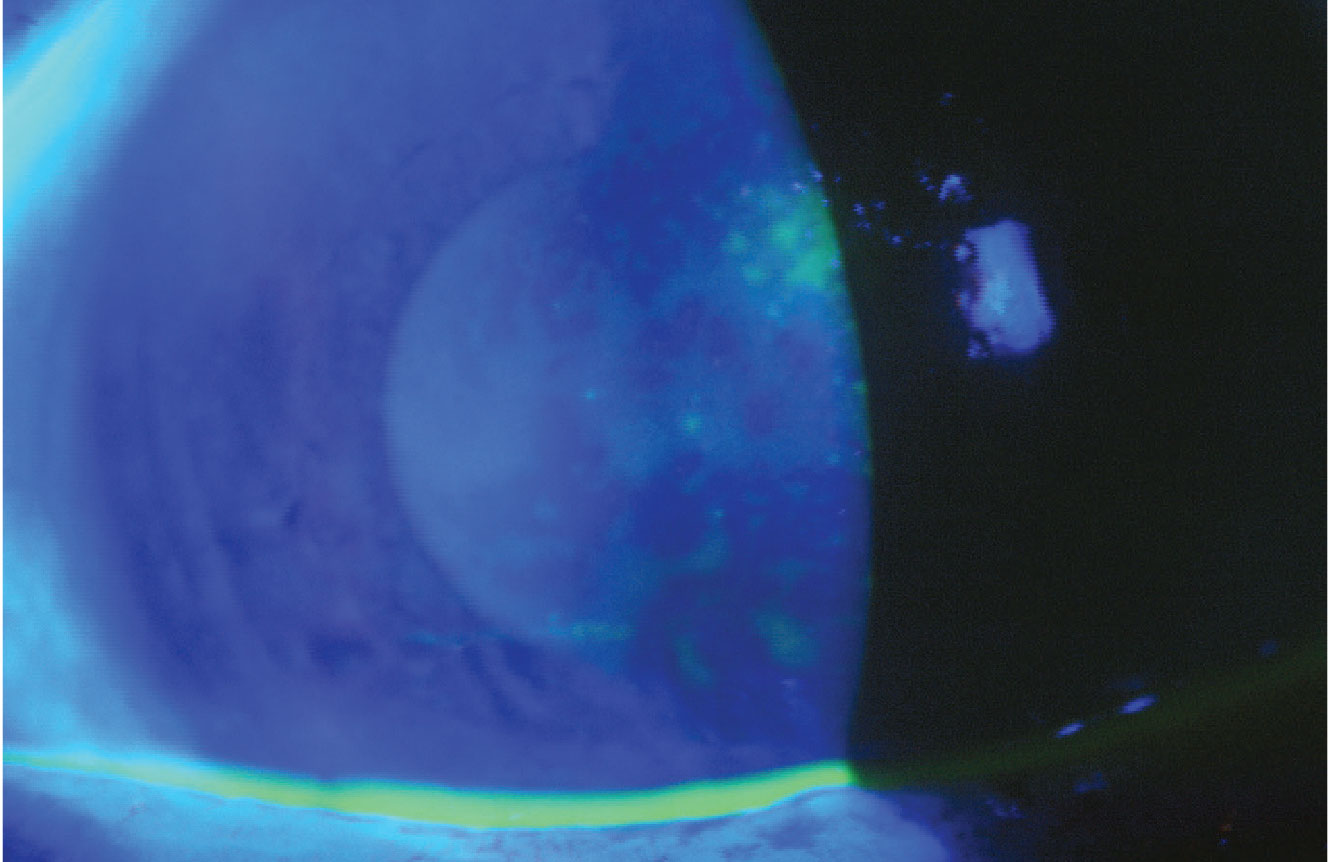

A 72-year-old female with cataract demonstrating a pattern of fluorescein staining consistent with aqueous tear layer deficiency. Image courtesy of Terrence P. O’Brien, MD. |

Dry eye is the top complaint among post-LASIK patients, with studies showing that 95 percent of them experience some manner of symptoms.2 Due to its suspected ubiquity in the general population, many suspect that LASIK exacerbates previously undiagnosed ocular surface disease. “Active screening for ocular surface disease is perhaps even more important with refractive surgery—because it’s an elective, voluntary procedure,” Dr. O’Brien says. “If OSD isn’t detected prior to an elective refractive surgery, the consequences can be even more significant for patient dissatisfaction and cause lingering ongoing problems.”

Preeya K. Gupta, MD, FACS, a cornea and cataract surgeon in Durham, North Carolina, believes ocular surface disease should be suspected in a majority of cataract patients. She co-authored a study of cataract patients with a mean age of 69.5 years and found that upwards of 80 percent who came in for a cataract evaluation had some sort of ocular surface disease dysfunction.3 “It’s actually more common than not that patients will present with dryness, though they may be asymptomatic,” Dr. Gupta says. “That kind of leaves us to say, ‘If I’m not seeing it in three out of four patients, maybe we’re not looking for it the right way or we’re not paying close enough attention to it.’ ”

Ocular surface disease increases with age, says Dr. O’Brien. “Since cataract is an age-related process and increases over time among that population, the two frequently overlap. It’s not infrequent that patients will have significant ocular surface disease concomitant with advancing cataracts,” he says. “Cataract surgeons really can’t ignore this common correlation. They have to really be on the lookout and identify or detect significant ocular surface disease and preferably address it in advance to achieve better outcomes. The patient will be less likely to have protracted healing and worsening of OSD after the cataract surgery. Multiple factors related to the cataract surgery itself can often exacerbate pre-existing ocular surface disease.”

Why the Ocular Surface Matters

“The air-tear film is one of the most important refractive surfaces in the eye, in addition to the lens,” says Dr. Gupta. “When we’re performing cataract surgery, we’re replacing the patient’s lens but if we don’t treat underlying ocular surface disease, we’re not really going to be giving our patients the best quality of vision that they expect because the air-tear interface is critical in vision quality.

“With any ocular surgery, not just cataract surgery, we can actually worsen ocular surface disease by disrupting corneal nerves,” she continues. “For some people, it’s temporary, but for others it can be a persistent problem and becomes a source of dissatisfaction to patients because they came in asking for you to improve their vision, you performed cataract surgery, but they come back saying their vision is terrible. They might be seeing 20/20 on a chart but when you actually look at everything all together, it’s their tear film that’s gotten worse over time. That in itself is something that can lead to dissatisfaction after surgery, as well as blurred vision postoperatively.”

|

|

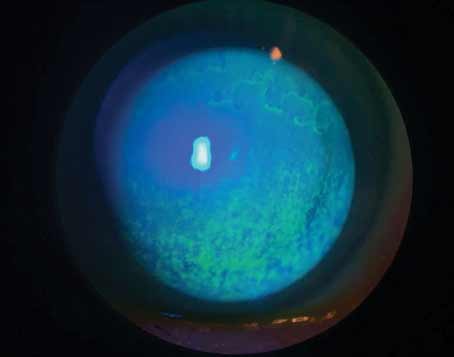

The tried-and-true therapies of warm compresses and digital massage are very beneficial for eyes with meibomian gland congestion or inspissation. |

The ocular surface’s condition can also influence IOL calculations and refractive measurements. One retrospective case series found that epithelial basement membrane dystrophy and Salzmann’s nodular degeneration altered the K measurements and affected the spherical and toric IOL power.4

“We know, when it comes to postoperative patient satisfaction, the precision of IOL calculations and refractive measurements prior to surgery, the ocular surface is increasingly important,” says Christopher E. Starr, MD, an associate professor of ophthalmology and director of the refractive surgery service at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York. “Toric IOLs, premium IOLs, EDOF lenses—all these things do better when the ocular surface and the cornea in particular are pristine and optimized.”

Defining ocular surface disease has been a challenge within the field. Bascom Palmer Eye Institute defines ocular surface disease as “disorders of the surface of the cornea” including “dry-eye syndrome, meibomian gland dysfunction, blepharitis, rosacea, allergies, scarring from glaucoma medications, chemical burns, thermal burns and immunological conditions such as Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid and Sjögren’s Syndrome.”5

More often than not, symptoms—which can include blurry vision, discomfort, pain, redness, itching—get lumped into the term “dry-eye,” but it’s much more complex. “For me, the distinction between the term ocular surface disease and dry-eye disease is an important one and it’s a message I’ve been trying to get out there for years now,” says Dr. Starr. “Stop calling all of this dry eye; dry eye is a subtype of ocular surface disease, and it’s one of many that can have ramifications and implications on refractive outcomes.”

Screening and Diagnostic Tools

Since ocular surface disease can take so many different forms and severities, an OSD initiative was undertaken by representatives from the ASCRS Cornea Clinical Committee, including Dr. Gupta and Dr. Starr. “The idea was to create a protocol/workflow algorithm to help people navigate OSD and to help these practices adopt something that will help them to not miss this and instead manage this proactively,” says Dr. Starr. The preoperative algorithm is freely accessible at www.ascrs.org.

• Questionnaires. One of the first steps in this algorithm is an ocular surface screening battery of questions. This isn’t new to cataract and refractive surgeons, and there are various validated dry-eye questionnaires available, including the Ocular Surface Disease Index, Dry Eye Questionnaire-5, McMonnies Dry Eye Questionnaire, Symptom Assessment in Dry Eye (SANDE), and Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness (SPEED) questionnaires. These have been evaluated for their discriminative ability in a prospective, investigator-masked, diagnostic accuracy study6 that found that the OSDI and SANDE scores had superior discriminative ability in detecting dry-eye signs compared with the others.

“A questionnaire is a great pre-screening tool that can often be sent even when the patient’s making the appointment to come in for a cataract evaluation,” says Dr. O’Brien. “The patient can receive this validated dry-eye questionnaire and upon arrival the team is even more alerted to the possibility or the actual likelihood of DED/OSD if the patient has a history of these conditions.”

Common questions may include asking about frequency and severity of grittiness, burning, irritation or eye fatigue; if they use eye drops and how often; if they wear contact lenses and for how long; and if one eye seems more impacted than the other.

“Even if people aren’t using a validated questionnaire from the National Eye Institute, or other questionnaires that have been shown to be validated, even just a few simple questions can be helpful,” continues Dr. O’Brien.

One important question to ask is about fluctuating vision. “I very much like to ask them about their blurry vision, specifically if it’s fluctuating or if it’s constant,” Dr. Gupta says. “Fluctuating blurred vision will often lead you to a diagnosis of dryness because cataracts do not typically cause fluctuation in vision, it’s more of a fixed level of blur. Ocular surface disease will cause fluctuating blurred vision because patients will have a varied tear film blink to blink.”

Dr. O’Brien notes that certain diseases and medications contribute to ocular surface disease, including Type 2 diabetes, hypertension and high blood pressure. “Those are often comorbid systemic conditions that contribute to dry eyes,” he says. “A careful review of medications is essential because sometimes over-the-counter medications are omitted by patients who don’t consider them to be medications because they’re not prescribed by a physician. Examples include anti-allergy medications and decongestants. Those are very drying but frequently patients will forget to mention unless you really probe for all medications being used.”

Dr. O’Brien says another class of medicines in use by many that are frequently ignored are sleep aids, such as benzodiazepines and soporifics that contribute to sleep. “Benadryl, which is an antihistamine, is taken by some to help go to sleep,” he says. “A lot of people take a low dose of a sedative hypnotic to help go to sleep and those all really contribute to ocular dryness.

“Diuretics are another group of medicines about which to inquire,” Dr. O’Brien continues. “Patients with high blood pressure are often on a diuretic and that’s very drying as well. That’s why high blood pressure is also frequently associated with dry-eye disease.”

Cataract surgeons should also make sure to ask if the patient has had prior LASIK surgery. “If they had it 20 or 25 years earlier, they may have forgotten to mention it,” Dr. O’Brien says. “That should be on our screening list because those patients may be more prone to develop dryness either prior to the cataract or certainly after the cataract because of their prior LASIK surgery. And of course, we want to know that because it can be more challenging to obtain an accurate determination of corneal power to select the desired intraocular lens power.”

• Testing. Now that the surgeon is armed with knowledge about symptoms, when the patient arrives in the office, specific testing will look for signs of ocular surface disease. At this point, osmolarity testing is a beneficial tool, and there are in-office, point-of-care tests available. Dr. O’Brien says he believes the field is “on the cusp of a significant paradigm shift in screening patients for more efficient/robust detection of ocular surface and dry-eye disease using a ‘multiplex’ point-of-care testing options that have recently become available. I have actually been talking about this for many years with great hope that this would someday become a reality.” He cites a tear lactoferrin assay that’s become available and a future Tear IgE test that will look for ocular allergy in the clinic.

Tear osmolarity testing has been around for years, and has its pros and cons, physicians say. “Hyperosmolarity is a fundamental finding in dry-eye disease,” says Dr. Gupta. “Osmolarity tests are readily available, but there’s a cost associated with them. A lot of insurance companies will reimburse for them, but some will not, so it depends on your region. Osmolarity has a very high specificity. If it’s abnormal, it’s very likely that the patient has dry eye, but it’s not necessarily a linear metric. We should know how the test works and be thoughtful about those aspects of it. But I do think it’s a good screening tool for dry eye and it’s easy to educate the patient when you tell them they have an abnormal number.”

Dr. Starr uses tear osmolarity and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) with his patients. “I use these with all of my patients, not just my pre-surgical patients,” he says. “Tear osmolarity is a fantastic test for dry-eye disease and it’s quantifiable, however, it doesn’t tell you a whole lot about other forms of ocular surface disease, whereas when MMP-9 is abnormal (the InflammaDry test measures this) then you know that the ocular surface is abnormally inflamed, and inflammation is certainly a result of chronic dry-eye disease. We know that inflammation is elevated in a lot of other ocular surface diseases that aren’t dry-eye disease: allergy; pterygium; some forms of blepharitis; epithelial basement membrane disease that can sometimes elevate MMP-9; and conjunctivitis. There are a lot of other things that can cause elevations in MMP-9 that are all abnormal but not dry-eye disease.”

One of the best tests that can be done is the tear-film breakup time, according to Dr. O’Brien. “We usually blink about every 12 to 15 seconds per minute,” he says. “The tears should try to last until the next blink. However, in many patients the tears are breaking up much sooner than that. In some patients with severe dry eye it’s almost instantaneous. In others, their tears break up after four to five seconds so they’re not making it until that next blink and that’s why they’re symptomatic with evaporative dry eye. Tear-film breakup is a very simple test that any clinician can perform and should complete as part of the screening. It’s very valuable information that’s obtained quickly.”

Dr. O’Brien cautions that these tests should be performed on eyes in their natural state, free of any diagnostic drops. “If considering testing tear-film osmolarity, the results will be unfortunately marginalized if anesthetic drops or dilating drops are instilled. That’s going to alter the osmolarity and affect other tear layer tests,” he says. “It’s better to observe the eye in its normal state.”

• Clinical exam. Dr. Starr says the clinical exam is often an area that surgeons in general don’t do because it can take up a lot of time. “As part of this algorithm, we needed to come up with a quick, pointed, catchy moniker for the ocular surface exam so that everybody does the steps with each visit,” he says. “We came up with something called Look, Lift, Pull, Push (LLPP).”

“As doctors, we have limited time and it’s hard for everybody to incorporate everything into their exam, so LLPP is meant to give people a framework and some guidance in how they can best approach screening their patients,” adds Dr. Gupta.

Dr. Starr walked through the steps in detail:

• Look: “When I walk into a room and start talking to the patient, I am honed in on their eyes, their blink, their symmetry between the eyes, looking for signs of facial rosacea, looking for incomplete blinks or exposure, lagophthalmos, scleral show—these types of things tell you so much and are often overlooked,” he says. “There’s so much important information that can be gleaned just from talking and observing the eye. ‘Look’ is also look under the slit lamp, look at the eyelid margin, look at the lashes, look for signs of anterior blepharitis, bacteria, biofilms and telangiectasia. Look at the cornea for signs of subtle corneal dystrophy, such as epithelial basement membrane dystrophy and conjunctival issues, etc.

“We usually have the patient look up and we have the patient look down,” Dr. Starr continues. “When the patient looks down, you can often see collarettes, and we now know collarettes on the eyelashes are pathognomonic for Demodex blepharitis. We know that when there are Demodex mites there’s a higher chance of bacterial colonization or superinfection. In the pre-surgical patient, that’s an important thing to identify, obviously, because of the risk of endophthalmitis and surgical infection.”

• Lift: “Lift means lift up the upper eyelid, and we often don’t do that. It’s a quick and easy thing. You just lift it up and examine the superior conjunctiva and the superior cornea which is often blocked by the upper lid unless you lift it up,” he says. “The reason why that’s important is that there are things that reside up there that can cause problems and lead to visually significant ocular surface disease, such as superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis and corneal dystrophies like EBMD or map-dot fingerprint, which often lives on the superior cornea, and you might completely miss it unless you examine that area.”

• Pull: “Pull the upper eyelid away from the eye to assess laxity. Floppy eyelid syndrome is a very common cause of ocular surface disease and chronic ocular surface issues and can have visual impact. Assessing that is important for everybody to do whether they’re pre-surgical or not,” Dr. Starr says.

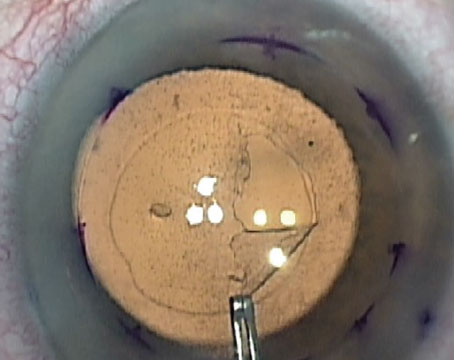

• Push: “The final part of the exam is pushing on the meibomian glands. Meibomian gland expression is often not done and it’s such important information,” he continues. “If you push on the meibomian glands and nothing comes out then you know that you’ve got obstructive MGD and you’re not going to have enough tear lipid and there’s going to be evaporation.”

Dr. O’Brien says meibography does help with looking at the health of the meibomian glands, but he stands by the practice of physically looking at the lids and manually expressing the meibomian glands as well.

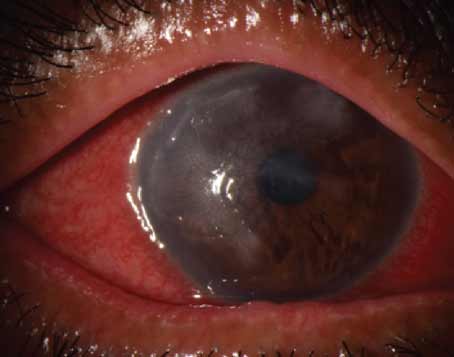

During the clinical exam, Dr. O’Brien performs corneal staining. “There’s fluorescein staining, which is beneficial, and even more beneficial is a vital stain such as lissamine green,” he says. “Lissamine green will detect ocular surface disease earlier with cells that are devitalized from chronic dryness of the surface, punctate epitheliopathy, whereas fluorescein will only detect cells that have already died so you’ll see erosions where cells have fallen out or dropped out. With lissamine green you’ll see cells that are still alive but they’re just not happy or healthy because of chronic dryness and inflammation of the ocular surface.”

|

|

A 59-year-old hyperope with decreasing tolerance to multifocal soft contact lens presenting for possible laser vision correction. Rose bengal demonstrates significant interpalpebral staining. |

Dr. Gupta notes that corneal staining is a late-stage dry-eye disease finding. “Initially, when patients have dry eye they won’t have corneal staining, and they may have higher symptoms than signs of dry-eye disease because they haven’t had these cycles of inflammation that lead to corneal decompensation,” she says. “Corneal staining can actually interfere with our measurements as well. We can sometimes get erroneous biometry measurements leading to inaccurate treatment plans.”

In the past, Schirmer’s testing was a common tool for ocular surface disease, but Dr. O’Brien says it became somewhat controversial due to difficulty interpreting results. “I agree that sometimes the value of the test may be limited or the validity may be questioned because in some patients there can be sort of a reflex tearing that’s induced by the strip,” he says. “The Schirmer I uses no anesthesia. I think that can be a better screening option than the Schirmer II, when you use anesthetic and then you test the amount of wetting on the little strip. On the Schirmer I, if you have next to nothing (zero or 1 mm only of wetting), the patient has severely aqueous deficient tears and that gives you some value. Sometimes with the Schirmer II, it’s difficult to interpret the meaning or the value of the test. That’s why a lot of doctors have abandoned Schirmer testing.”

Advances in imaging technology have also helped in diagnosing ocular surface disease. “The machines we’re using to get topography, such as the Oculus, can also measure the tear meniscus height,” Dr. O’Brien continues, “and that can be a quantifiable measurement. If you have a low tear meniscus height then the person is at risk.”

Treatment Planning

If a surgeon has discovered signs of visually significant ocular surface disease, this must be explained to the patient.

“Often all of these symptoms will get worse after surgery because of the incisions, drops, preservatives and all of the trauma of surgery,” Dr. Starr says. “If you don’t pick up on these before the surgery and discuss it with the patient and it worsens or becomes more visually symptomatic to the patient postoperatively, then they view it as a surgical complication. Having the discussion and instituting treatment makes sense on so many levels and will improve outcomes and reduce the perceived complication rates.”

It’s best to delay cataract or refractive surgery and begin treating the subtype of ocular surface disease. “Most of the time patients presenting are eager to have either cataract surgery or refractive surgery,” Dr. O’Brien says. “The teams have been trained to be very efficient at screening. You have to make sure that there’s a way to ‘pump the brakes’ prior to the patients just being rushed into the operating room. That’s where some of the really unfortunate cases occur. Perhaps they could’ve been prevented if there was a slower, more robust screening and a slower-to-procedure process where treatment had a chance to work. Even for moderately severe ocular surface disease, surgery may have to be postponed for at least four to six weeks to allow the various therapies to have a chance to really bring the ocular surface disease under better control and to allow more accurate preoperative measurements.”

Treatment depends on the severity of a patient’s disease. A severity grading after performing this diagnostic testing can help guide treatment. The OSDI defines the ocular surface as normal (0-12 points), mild (13-22 points), moderate (23-32 points) or severe disease (33-100 points).7

“For most patients that fall into the mild or early group of dry-eye disease, treatment can sometimes be as simple as education about sleeping under a ceiling fan or if they have air conditioning blowing into their face because they’re a truck driver,” says Dr. O’Brien. “Or they work at a computer and that’s almost everybody these days. They need education about screen time. We usually recommend the rule of 20-20-20: every 20 minutes the individual takes a break for 20 seconds and simply looks off in the distance for 20 feet. That interrupts the cycle of locking into the screen and blink rate going down and evaporation of tears going up. The 20-20-20 rule can be helpful.

“Also, educating about medications that they may be taking, over-the-counter, anti-allergy drugs, antihistamines, medicines for sleeping and antidepressants is useful,” he continues. “We have a high number of people that have been prescribed these antidepressant medicines that have some anticholinergic effects so people’s eyes become very dry with those as well. Behavior modification can help, such as drinking more water, especially if they work outdoors or exercise in warm places.”

Tear replacement and lid hygiene are among other first-line treatments for those in the mild group. “Lid hygiene is very important so we recommend cleaning the eyelids and the eyelashes with some type of dilute shampoo,” says Dr. O’Brien. “Even baby shampoos contain detergents so we prefer more of a commercially available foaming lid cleanser that would help remove tear debris from the lids and lashes that can end up in the tear film. Then, especially for those with meibomian gland congestion or inspissation, the use of warm compresses for localized hyperthermia with accompanying massage is very beneficial.”

Nutritional supplements such as Omega-3 fatty acids have also been shown to ameliorate dry-eye symptoms.8

There’s no one perfect treatment, says Dr. Gupta, but for a lot of patients something that’s very quick can be a topical steroid. “After patients are on the topical steroid for about two weeks, we’ll have them back to repeat their testing and if things are better, we may be able to schedule the surgery, but they have to prove their surface is better before we go to surgery,” she says. “If the patient has a risk of prolonged dryness postoperatively I have a low threshold to not only prescribe a topical steroid but to also put them on something like a chronic immunomodulating medication to help with their inflammation, which will help postoperatively as well.”

Dr. O’Brien says this includes cyclosporine drugs or lifitegrast. “Usually these patients are anxious to have their surgery and we want to try to get the ocular surface under control more quickly, and we may also give a brief pulse of a topical corticosteroid along with the immune modulation to try to accelerate the anti-inflammatory effects to bring the condition under control,” he says.

“Those patients who have more significant disease, in addition to the corticosteroids and immunomodulatory agents such as cyclosporine or lifitegrast, we often will give a brief systemic course of doxycycline or minocycline as an immune modulator to help with ocular surface inflammation or meibomian gland inspissation,” Dr. O’Brien continues. “For some patients where there’s a significant evaporative component we may place punctal plugs. For people with very significant meibomian gland disease we might recommend even more aggressive treatment, for instance a pulsatile thermal physical therapy such as LipiFlow, iLux or a similar commercially available treatment.”

For the very severe cases, treatment may even include autologous serum tears for at least six to eight weeks prior to being able to safely undergo the cataract procedure without creating a postoperative imbalance that could be very detrimental, he says.

If the patient is found to have other corneal diseases, those must be addressed prior to surgery. Salzmann’s nodular degeneration is due to chronic inflammation of the eyelids and lashes, causing scar tissue to build up on the cornea (the nodules). “Those should be removed because they create a lot of irregular astigmatism and you’d get very abnormal readings,” says Dr. O’Brien.

“Another common condition that may affect about 2 percent of the general population is epithelial basement membrane dystrophy or anterior basement membrane dystrophy,” Dr. O’Brien adds. “That usually should be addressed prior to the cataract surgery by removing the epithelium either through excimer laser phototherapeutic keratectomy or manually, such as with a corneal burr, so that the cornea is smoother, otherwise it can affect the accuracy of biometry and intraocular lens power determination.”

After giving these various therapies a chance to work, patients should be brought back to the office and surgeons should repeat the screening process to be sure the ocular surface disease is no longer visually significant.

However, Dr. O’Brien cautions that patients should continue their ocular surface disease treatments postoperatively. “You have to continue treatments postoperatively to help bring things under control and to prevent them from getting worse, because both cataract and refractive surgery leave the eyes drier for some time, about six to eight weeks—and maybe even up to three to six months with LASIK,” he says.

Dr. O’Brien notes that several components of cataract surgery can contribute to postoperative dryness. “For example, there’s the ocular anesthetics that are used, the multiple drops that contain preservatives, the incision itself—that’s been looked at,” he says. “If someone’s having femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery the suction device of the laser can affect the ocular surface. The main and arcuate corneal incisions may affect corneal sensation. The ocular surface is prone to temporary or transient damage from dryness during cataract surgery, as well as the preservative-containing eye drops.” n

Dr. Gupta is a consultant to Alcon, Allergan, Sight Sciences, Novartis and Azura Ophthalmics. Dr. O’Brien reports no disclosures. Dr. Starr is a consultant for Trukera Medical and Quidel.

1. Dana R, Meunier J, Markowitz JT, Joseph C, Siffel C. Patient-reported burden of dry eye disease in the United States: Results of an online cross-sectional survey. Am J Ophthalmol 2020;216:7-17.

2. Yu EY, Leung A, Rao S, Lam DS. Effect of laser in situ keratomileusis on tear stability. Ophthalmology 2000;107:12:2131-5.

3. Gupta PK, Drinkwater OJ, VanDusen KW, Brissette AR, Starr CE. Prevalence of ocular surface dysfunction in patients presenting for cataract surgery evaluation. J Cataract Refract Surg 2018;44:9:1090-1096.

4. Goerlitz-Jessen MF, Gupta PK, Kim T. Impact of epithelial basement membrane dystrophy and Salzmann nodular degeneration on biometry measurements. J Cataract Refract Surg 2019;45:8:1119-1123.

5. Ocular Surface Disease. https://umiamihealth.org/en/bascom-palmer-eye-institute/specialties/corneal-and-external-diseases/ocular-surface-disease. Accessed June 7, 2023.

6. Wang MTM, Xue AL, Craig JP. Comparative evaluation of 5 validated symptom questionnaires as screening instruments for dry eye disease. JAMA Ophthalmol 2019;137:2:228–229.

7. Miller KL, Walt JG, Mink DR, et al. Minimal clinically important difference for the Ocular Surface Disease Index. Arch Ophthalmol 2010;128:1:94–101.

8. Giannaccare G, Pellegrini M, Sebastiani S, Bernabei F, Roda M, Taroni L, Versura P, Campos EC. Efficacy of Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation for treatment of dry eye disease: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Cornea 2019;38:5:565-573.