Presentation

A 57-year-old male presented to the neuro-ophthalmology clinic at Wills Eye Hospital with the complaint of blurred vision in both eyes. He had been referred by a general ophthalmologist after a new pair of soft contact lenses had not improved his vision. According to the patient, his symptoms had been slowly progressive over the past two to three months. Of note, he had presented to an emergency room two months prior with symptoms of flushing and akathisia. He was found to have a blood pressure of 240/120 at that time and was subsequently admitted to the hospital. After an extensive workup, he was found to have spiking cortisol levels, but ruled out for a pheochromocytoma.

Medical History

The patient's medical history was significant for hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. His medications included Toprol, Relacore, magnesium and omega-3 fatty acids. He was allergic to Lamictal. His family history was significant for hypertension. He does not smoke, uses occasional alcohol and has never used illicit drugs.

Examination

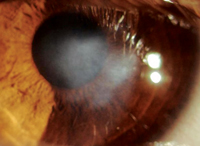

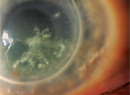

Office examination revealed a best-corrected visual acuity of 20/400 in the right eye and count fingers at 4 feet in the left eye. There was no improvement with pinhole in either eye. His pupillary reactions were sluggish in both eyes with a trace relative afferent defect on the left. Extraocular motility was full in both eyes. Intraocular pressures were 12 mmHg in both eyes by applanation tonometry. During color plate testing, the right eye was able to see the test plate only, and no plates were seen by the left. Slit-lamp examination was unremarkable. His dilated fundus exam was significant for hyperemia and mild edema of the retinal nerve fiber layer surrounding both nerves. No optic nerve pallor was appreciated. Goldmann visual fields showed a dense central scotoma in the right eye and a dense cecocentral scotoma in the left. A multifocal electroretinogram (mfERG) was ordered and is shown below (See Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1 (left). mfERG of the right eye demonstrating a significantly reduced foveal peak.

Figure 2 (right). mfERG of the left eye demonstrating a nearly absent foveal peak.

Diagnosis and Workup

The patient subsequently saw a neurologist for further evaluation. Additional history was obtained and was significant for lower extremity parasthesias that had slowly progressed over the past year. Examination demonstrated reduced deep tendon reflexes (DTRs) in the lower extremities, and decreased vibration and proprioception in his toes. The differential diagnosis at that time included toxic optic neuropathy, paraneoplastic syndrome, and neuropathy secondary to a vascular insult. A magnetic resonance image of the orbits and brain with gadolinium, a lumbar puncture and a paraneoplastic blood workup were ordered and were reported as normal.

Shortly thereafter, the patient underwent heavy metal testing as advised by his chiropractor. The toxic metal profile revealed elevated levels of mercury and lead, and the diagnosis of toxic optic neuropathy was made.

Discussion

Toxic optic neuropathies typically present with a gradually progressive, bilaterally symmetric, painless vision loss affecting central vision and causing a central or cecocentral scotoma. Heavy metals implicated in pathology of the visual system include lead and mercury. Lead poisoning is the most common cause of chronic metal poisoning. Sources of lead include old paint, improperly glazed pottery, indoor shooting ranges, old plumbing, contaminated herbal medications and exposure to glassmaking, battery burning, soldering, bronzing and brassmaking.

Historically, Benjamin Franklin was the first to recognize abdominal colic and peripheral neuropathy as signs of plumbism. The United States banned the commercial sale of lead-based paint in 1972, and the sale of leaded gasoline in early 1990s.

Absorption of lead is via the respiratory and gastrointestinal tract. Greater than 90 percent is stored in bone, with a half-life of 30 years. The most common symptom in lead poisoning is systemic hypertension. In the visual system, the lens, extraocular and intraocular muscles, the retina, the optic nerve and radiations, and the visual cortex have all been implicated in lead toxicity. Optic neuritis is believed to be the most common ocular manifestation, resulting in a central or cecocentral scotoma. Studies have also shown that the sensitivity and amplitude of the a- and b-waves of the dark-adapted ERG are decreased.

Additional manifestations of lead poisoning include altered mental status, seizures, ataxia, headache, irritability, depression, fatigue, memory deficit, parasthesias, motor weakness (classic wrist drop), depressed DTRs, abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, renal insufficiency, anemia, impotence, sterility and premature birth. Diagnosis is best made via venous blood sampling. Treatment includes removing the source of exposure and chelation with intramuscular dimercaprol (BAL) or CaNa2 (calcium disodium) EDTA and oral succimer (for patients with encephalopathy), or oral succimer alone.

Mercury is a naturally occurring metal that exists in three forms, each with characteristic and distinct toxicities: elemental mercury, inorganic mercury salts and organic mercury. Elemental mercury is absorbed primarily via inhalation and crosses the blood-brain barrier. Sources include battery and thermometer manufacture, dentistry, jewelry and lamp manufacture and photography. Inorganic mercury salts are absorbed via inhalation, the GI tract and dermally. They are severely corrosive to the GI mucosa. These salts are used in taxidermy, fur processing, tannery work and in the manufacture of button batteries, fireworks, inks and vinyl chloride. Organic mercury is well-absorbed via the GI tract and readily crosses the blood-brain barrier. Sources include seafood, fungicides, pesticides, bactericides and embalming.

The ocular manifestations of mercury toxicity are usually limited to constriction of the visual fields. Systemic symptoms include erethism (anxiety, depression, irritability, mania, sleep disturbances and memory loss), acrodynia (sweating, hypertension, tachycardia, pruritis, weakness, insomnia, anorexia—often mimics pheochromocytoma), tremor, parasthesias, ataxia, hearing impairment, mucosal ulcerations, abdominal pain, poor appetite and renal failure. A 24-hour urine collection is the gold standard for diagnosis. Treatment includes removing the source of exposure and chelation with succimer, dimercaprol, or D-penicillamine. Hemodialysis has been used for patients with renal failure.

Follow-up

Shortly after the diagnosis, the patient began treatment with oral succimer and CaNa2 EDTA. He was seen in follow-up two weeks after starting chelation, and he felt that his visual acuity and color vision were subjectively improved.

Objectively, however, his Snellen visual acuity and color plate testing were unchanged. Goldmann visual field testing did show an improvement in the density of the bilateral cecocentral scotomas. Repeat testing for mercury and lead levels were subsequently scheduled.

Dr. Fintak is a senior resident at Wills Eye Hospital and section editor for the Wills Resident Case Series.