For the past two decades, the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network has centered its mission on collaborative research that sheds light on benefits and risks to certain treatments for patients with diabetic retinopathy and other retinal diseases. Ophthalmologists perhaps know better than any other type of physician the ubiquity of diabetes and its consequences to individuals. The advent of therapies such as anti-VEGF have given retina specialists a lot to consider in their approach to treatment, and there’s constantly something new to keep an eye on.

We spoke with some of the researchers who took part in a few of the DRCR’s key studies in recent years and asked how each Protocol trial has impacted treatment paradigms and what questions are yet to be answered.

Protocol S

Protocol S caused a significant shift in treatment of proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Published in 2015, it compared panretinal photocoagulation vs. the anti-VEGF ranibizumab.1 At the time, PRP was the standard of care, but there were recognized risks associated with it, such as retinal damage that could result in peripheral vision loss or worsening diabetic macular edema. Protocol S questioned if ranibizumab as first-line treatment would be non-inferior to PRP.

A total of 305 adults with PDR were randomized into the ranibizumab group (n=191 eyes): intravitreal 0.5 mg ranibizumab with PRP if treatment failed; ranibizumab as needed for DME; and the PRP group (n=203 eyes): PRP; ranibizumab as needed for DME.1 Visual acuity results showed treatment with ranibizumab was non-inferior to PRP treatment at two years. The ranibizumab group had a mean visual acuity letter improvement of +2.8 at two years vs. +0.2 in the PRP group.

Five-year results of Protocol S showed severe vision loss and PDR complications were rare in both the ranibizumab and PRP groups, although the ranibizumab group had lower rates of developing diabetic macular edema and less visual field loss.2 Protocol S gave confidence in anti-VEGF as initial treatment, however, there were patient factors for every ophthalmologist to consider before diving into it, including patient compliance. Even with the DRCR’s considerable resources to reach patients—including investigators, coordinators and a third-party search service—the five-year results showed relatively high rates of loss-to-follow-up: 74 eyes in the ranibizumab group didn’t complete their five-year visit (53 withdrawn, 21 died); and 80 eyes in the PRP group (65 withdrawn, 15 died).2

Jennifer K. Sun, MD, MPH, an associate professor of ophthalmology at Harvard University, helps lead the DRCR Retina Network’s diabetes research initiatives, and says, despite Protocol S’ consistent results, it spurred discussions among those in the field.

“There’s been a lot of discussion in the years since the primary results of Protocol S were released in 2015 around the fact that anti-VEGF intervention is a very effective therapy in terms of regressing retinal neovascularization, but frequently it’s not a durable therapy,” she says. “Patients with proliferative retinopathy are at pretty high risk for missing follow-up visits, and there’s a whole variety of reasons why that happens. Even though they may have been doing very well with anti-VEGF, once that effect wears off and the vessels start growing again, if they miss follow-up visits, occasionally we’ll see patients come back in who have really florid retinal neovascularization with potential vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachments. We just hope we can get back in and treat that before they have irreversible vision loss.”

Dr. Sun says the majority of clinicians these days in practice are probably using a combination of the two treatments for many of their patients. “One of the next studies I’d like to see would be a very careful characterization of combination treatment therapy with both anti-VEGF and PRP—to understand what the outcomes are,” she says. “Would that give us a more durable response than anti-VEGF therapy alone over the long term while still reducing rates of diabetic macular edema compared to PRP alone?”

Protocol T and Protocol AC

It’s not uncommon for the results of one Protocol study to inspire another. For example, Protocol I, published in 2010, looked at treatments for center-involved DME and determined that eyes treated with ranibizumab 0.5 mg, with prompt or deferred focal/grid laser demonstrated superior visual improvements vs. the other groups: laser alone vs. intravitreal triamcinolone plus focal/grid laser.3 Prior to ranibizumab’s FDA approval for DME, bevacizumab (Avastin) was being used off-label, spurring the DRCR to organize Protocol T to compare ranibizumab and bevacizumab for DME. However, in the process of beginning the study, the FDA approved aflibercept for neovascular AMD, thus it was added to Protocol T.

In the study, 660 eyes with a visual acuity ranging from 20/32 to 20/320 and center-involving DME were randomized into one of the three anti-VEGF treatment groups. Study participants couldn’t have undergone anti-VEGF therapy in the previous 12 months, nor any laser or steroids for DME in the prior four months.4 The primary outcome was the mean change in visual acuity letter score from baseline to one year. Aflibercept showed the greatest improvement, with a mean of +13.3 letters gained, vs. +11.2 with ranibizumab vs. +9.7 with bevacizumab. However, at two years, aflibercept and ranibizumab showed no differences between the two groups, yet bevacizumab remained inferior to aflibercept but not ranibizumab.

“Protocol T needed to tackle this question of finding out if one or more of these therapies were better than the others not only to help us give the most effective treatment, but also because there’s a huge cost difference between these agents,” says Dante Pieramici, MD, a member of the DRCR Protocol T writing committee and a private practitioner in Santa Barbara, California. “Avastin is less than $100 per injection, while the others are upwards of $1,500 to $2,000 each.

“Over a two-year period, both of the more expensive drugs turned out to be better at improving vision and reducing retinal thickness, but most of this was driven by patients who had worse disease,” he continues. “So, if you did a subgroup analysis of patients who had vision better than 20/50 compared to those that had 20/50 vision or worse at baseline, you found that there really wasn’t a big difference between the drugs as far as visual acuity was concerned. Whereas in the patients who had worse vision at baseline (20/50 or worse), most of that difference was driven by this group of patients.”

Further questions were raised from Protocol T, though, particularly in response to insurance mandates on step therapy.

“It was very clear that after Protocol T, the standard of care became treatment with aflibercept or possibly ranibizumab in eyes with moderate or worse vision impairment,” says Dr. Sun. “That being said, we know that there are also differences in terms of cost and availability of medications and we were starting to see, as practitioners, that step therapy was being mandated by private payers more frequently over the previous few years. No one had actually done a careful study to say ‘would this kind of approach potentially be harmful to patients?’ ”

This was the origin of Protocol AC in which patients were either started on bevacizumab and transitioned to aflibercept at 12 weeks or later (if criteria were met) or were placed in an aflibercept monotherapy group.5

“We wanted to know, if you started with the less expensive therapy and switched, if there wasn’t a good response, would that put the patients at a disadvantage?” says Dr. Pieramici. Medicare data in the study reports the cost of aflibercept at $1,830 vs. $70 per dose of bevacizumab.

“We had very specific switch criteria,” says Dr. Sun. As stated in the study, switch criteria included: persistent center-involved diabetic macular edema (defined as the central subfield thickness being above the eligibility threshold); an adequately treated eye (administration of bevacizumab injections at the previous two consecutive visits); no recent improvement in eye condition (no improvement of visual acuity by ≥5 letters and no decrease in central subfield thickness of ≥10 percent as compared with each of the two preceding visits or between each of the two preceding visits); and suboptimal vision (visual acuity, 20/50 or worse before 24 weeks or 20/32 or worse at 24 weeks or later).5

“Over the course of the study, the huge majority of eyes in the bevacizumab group did end up switching—about 70 percent by the end of two years,” continues Dr. Sun. “The majority of them switched within the first year of treatment, but we found that over two years, we really didn’t see differences in terms of mean change in visual acuity from baseline to two years.” At two years, the mean change in visual acuity from baseline was 14.7±14.5 letters in the aflibercept-monotherapy group (in 132 eyes) and 15.9±12.4 letters in the bevacizumab-first group (in 128 eyes), with an adjusted between-group difference of −1.8 letters (95% CI, −4.9 to 1.2).5

“When we look at the retinal thickness outcomes, the eyes that were treated with aflibercept first probably had slightly better improvement in retinal thickness early on, but again, by the end of two years, the bevacizumab-first group had caught up very nicely and had very similar results,” Dr. Sun says. The study reported similar percentages of eyes with a central subfield thickness below thresholds for diabetic macular edema: 60 percent in the aflibercept-monotherapy group and 55 percent in the bevacizumab-first group.5

“The similarity between the visual acuity results in the two groups is there, whether you look at mean change in vision or whether you look at thresholds of vision improvement,” Dr. Sun summarizes. “What Protocol AC does to some extent is give us a standardized retreatment regimen and criteria for step therapy that we haven’t had before in the community, with very good characterization of what happens if you use the bevacizumab-first strategy with rescue with aflibercept as needed (if you do it the way we did in the study). If we’re using that kind of approach, then we’re able to reassure our patients and ourselves that the visual outcomes are excellent over two years and very similar to treating with aflibercept from the beginning.”

She warns other practitioners not to take this study as blanket approval for any step-therapy regimen. “If you use different anti-VEGF agents or a different treatment algorithm, you may end up with different results. Another factor that’s important to recognize is that we followed these patients very carefully in the clinical study. We were getting very frequent imaging, frequent follow-up visits, and those are things to pay attention to, not just that you’re using the same agents, but that you’re also following and managing the patient similarly,” she says.

Both Dr. Sun and Dr. Pieramici say this study may be further challenged as new agents come to market, such as faricimab (Vabysmo), high-dose aflibercept (Eylea) and biosimilars for bevacizumab.

“Now we’re wondering how these will fit into treatment. What would it look like if we start our diabetic macular edema patients on Vabysmo or Eylea? And if there’s a biosimilar for Avastin, then it will likely increase the price of Avastin, which eliminates the cost savings,” says Dr. Pieramici.

“The question will always arise as new agents come into the market and are approved, how they compare to what’s already out there,” adds Dr. Sun. “It’s difficult to know when it’s optimal to perform the next comparative effectiveness study. There will be questions about how different agents perform. There are a lot of new treatments that are out there and biosimilars are coming to the market. It’s hard to do a study that addresses each and every single one of them, but it’s something that every now and then might be worth doing so that patients have the best data possible to make their decisions.”

|

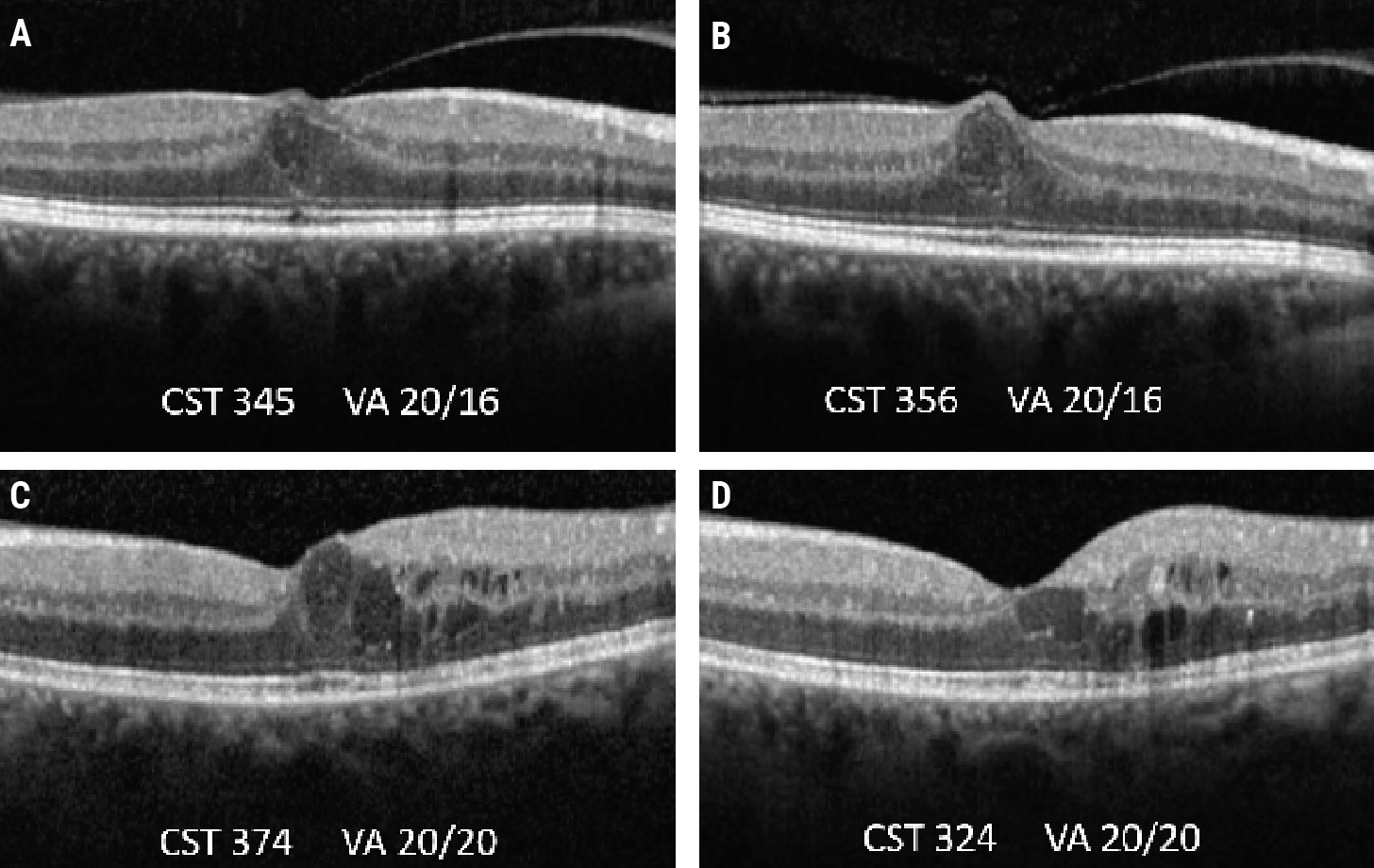

| Protocol V investigated the idea of observation vs. injections for patients with center-involved DME but good visual acuity. In these OCT scans of two patients with center-involved DME who were observed and didn’t receive treatment over a two-year period (baseline A and C, two-year follow-up B and D), both patients had residual edema yet maintained their baseline visual acuity. |

Protocol V

There’s no shortage of questions about when and which anti-VEGF therapies to use on diabetes patients, and Protocol V asked: “Should we be starting anti-VEGF immediately in everybody who has center-involved diabetic macular edema, or in eyes that start with good vision, despite CI-DME, is it okay to hold off on injections?”

Dr. Sun says Protocol V stemmed from Protocol I and Protocol T. “We know that DME can wax and wane, and sometimes you can improve spontaneously,” she says. “Protocol V (published in 2019) arose from a discussion I was having with a fellow of mine at Joslin Diabetes Center, who saw a patient in clinic right after the Protocol I results were released, showing anti-VEGF should really be the new treatment standard for CI-DME. And she said, ‘Dr. Sun, this patient has CI-DME and I know that the new study shows that we should use anti-VEGF treatment, but her vision is 20/20 and she has no visual symptoms. Is it really worth starting multiple years’ worth of injections for her in this eye that’s seeing so well?’ ”

Up until this time, all of the DRCR studies had included eyes with some level of visual impairment, usually 20/32 or worse, she explains. “In Protocol V, which included eyes that were seeing well (20/25 or better) despite having CI-DME, we randomized them to either immediate anti-VEGF, laser treatment or just observation initially,” says Dr. Sun. “Again, these were just initial management strategies. Over the course of the study, if the eyes in the laser or the observation groups were starting to lose vision, then we went ahead and treated them with anti-VEGF. At two years we found that the groups all did very similarly; they all did very well. The average vision at the end of the two-year study was 20/20 in each of the groups and so we concluded that it’s pretty safe to hold off on treatment initially in eyes with good vision and CI-DME, as long as you’re following them carefully and you’re instituting anti-VEGF therapy if the vision starts to worsen.”6

Since these results were released, Dr. Sun thinks there’s been a fairly widespread recognition that this is a reasonable strategy. “But, this isn’t to say that in any individual patient there might be characteristics that might make you choose to be more aggressive about starting therapy,” she says. “Some patients have a faster need for visual recovery that makes them interested in starting therapy earlier. I think overall there’s been pretty good uptake across the community that there’s not a need to rush into treatment for everyone with center-involved DME as long as the starting vision is good and they are able to follow-up as recommended.”

|

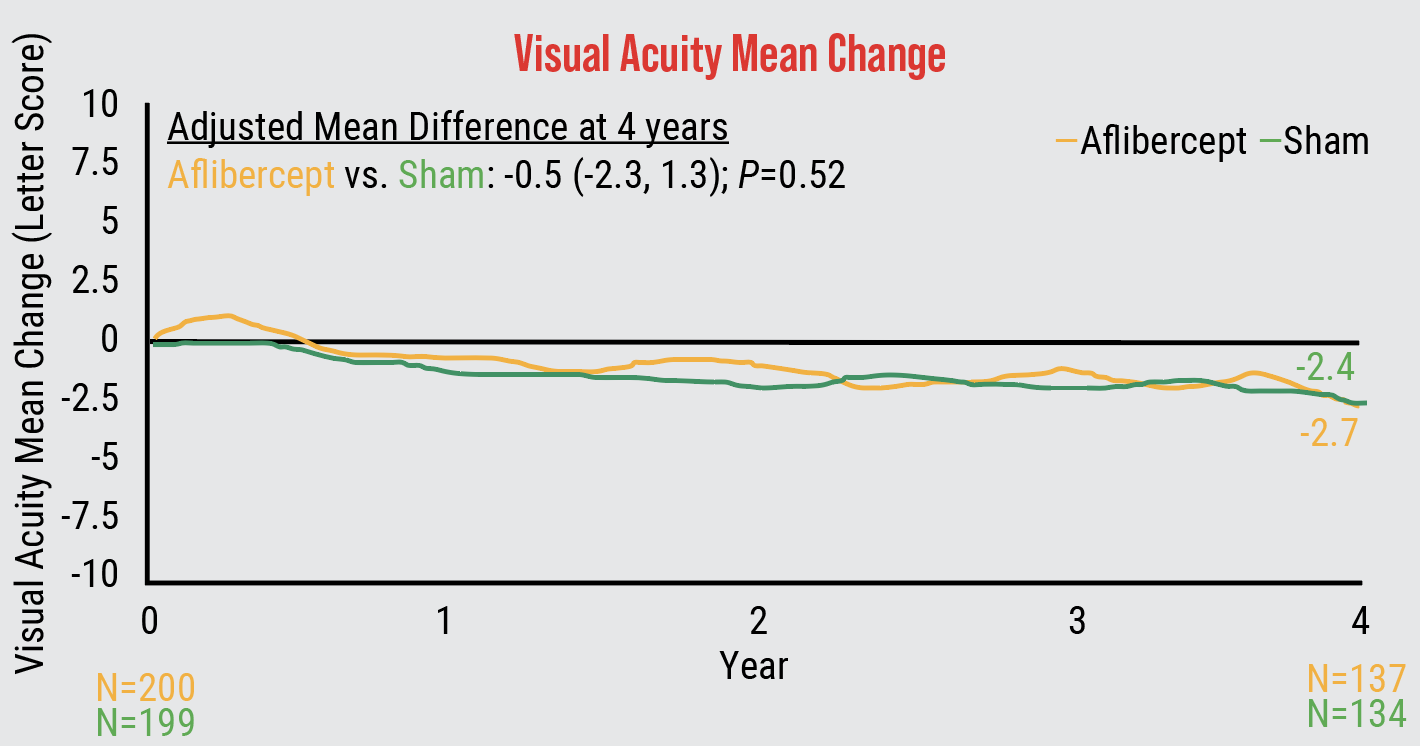

| Four-year findings from Protocol W showed that patients with non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy gained no visual acuity benefit with early anti-VEGF treatment. |

Protocol W

In the same wheelhouse as Protocol V, the more recent Protocol W also weighed the risks of monitoring disease progression vs. immediate anti-VEGF therapy, this time for patients with non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Earlier this year, four-year results from Protocol W were released and confirmed that early treatment of NPDR with anti-VEGF offered no long-term visual acuity benefit.7

“The goal was to figure out when is the best time to start anti-VEGF for patients,” says Raj Maturi, MD, of Indiana University School of Medicine and Retina Partners Midwest and chair of the protocol report. “We already know that anti-VEGF works really well when patients have diabetic macular edema and when they have proliferative diabetic retinopathy. However, what we don’t know is, is it useful to utilize these drugs even before the onset of these two key complications of diabetes, would it give better visual acuity outcomes?”

Protocol W was designed as a four-year study, he continues. The study included 328 patients (399 eyes) who were randomized into 2-mg aflibercept injections vs. sham injections. Injections were administered at one month, two months, four months and every four months for the first two years, and then continued quarterly through year four unless the eye improved to mild disease. Any eyes that developed vision-threatening complications were given additional anti-VEGF injections as needed.

“First, we wanted to see if there would be a difference in retinopathy development progression with anti-VEGF vs. observation. At two years we did see retinopathy levels decrease with treatment. Around this same time, the PANORAMA trial results were released and confirmed our findings as well,” Dr. Maturi says.

PANORAMA was a randomized clinical trial that investigated if treatment of moderately severe to severe NPDR with aflibercept injections would result in 2-step or greater improvement on the Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale in more eyes, fewer vision-threatening complications, and fewer center-involved diabetic macular edema events from baseline through 100 weeks compared with sham injections.8

Next was the more important question of visual acuity. “We needed four years to observe what would happen and we showed that there was no visual acuity difference at all between patients who got early treatment vs. who were observed until they developed one of the two key features PDR or DME,” says Dr. Maturi. The four-year cumulative probability of developing PDR or center-involved DME was 33.9 percent in the aflibercept group and 56.9 percent in the sham group (p<0.001). The mean change in visual acuity from baseline to four years was -2.7 ±6.5 letters in the aflibercept group and -2.4 ±5.8 letters in the sham group (p=0.52).7

Dr. Maturi admits to being a little surprised by the results. “As physicians, we want to treat patients with the goal of getting a functionally beneficial outcome,” he says. “Looking at the outcomes and how similar they were, it tells us, if it’s still functionally beneficial to wait, then maybe holding off on treatment is reasonable.”

The researchers involved in the study also looked closely at subgroups to see if they could find statistically significant results. “We created a subgroup analysis based on baseline diabetic retinopathy level, the presence of non-central DME, race and sex to see if any of these criteria mattered and none of these groups cleared zero, which is none of them favored aflibercept in a statistically significant manner,” Dr. Maturi says.

Some may argue that even if there’s no difference in visual outcomes, treating the patient anyway will help improve their diabetic retinopathy levels. Dr. Maturi says to consider the burden, cost and risk of injections on the patient’s behalf. “The patients who were randomized to the aflibercept group ended up getting 13 injections over this four-year period and in the sham group, the average was only 3.5—almost 10 injection difference between the two groups,” he says, amounting to an average cost of $20,000 per patient.

Dr. Maturi says Protocol W establishes what the right level before treatment is, yet there are always outliers. “There might be a few patients who still, despite the study, end up getting treated a little earlier—maybe they’re on dialysis, are at risk for loss-to-follow-up, are worried about their fellow eye that has severe disease and have NPDR in the fellow eye. It may be warranted to treat those eyes earlier,” he says. “We didn’t study certain subgroups, and clinician judgment is paramount. However, large studies like this give us some really good data that we can bank on as to which general, large groups of patients need treatment and at what point.”

He remains concerned about the progression of diabetic retinopathy even with treatment. “I think the biggest takeaway here is that with or without injections, diabetic retinopathy is a disease that progresses rapidly. The majority of patients progressed to PDR when they had baseline NPDR and not to DME with vision loss. Looking for signs of PDR in these patients that follow up is a really important thing. If you have a patient with NPDR, especially if it’s in the moderate to severe range, every three to four month follow-up is essentially what the AAO practice guidelines say,” Dr. Maturi says. “Considering other treatment modalities—PRP or even vitrectomy—may be beneficial in patients with diabetic retinopathy to halt their progression.”

Final Takeaways

Dr. Sun says, “We’ve now had about 20 years’ worth of studies in diabetic eye disease performed by the DRCR Network and it’s really been a privilege to be part of this era with the introduction of anti-VEGF. I think the take-home message that we see across our studies is that anti-VEGF is a very effective treatment for diabetic macular edema and proliferative retinopathy. It’s first-line treatment for many of our patients with diabetic macular edema and vision loss and it works very well for our patients that have proliferative disease.

“Some of the importance of the recent studies has also been to show us not just when eyes should get treated with anti-VEGF and how to treat them with anti-VEGF, but also when you can hold back on treatment, when it’s safe to not give injections, as long as you know that this patient will be good with follow up, will come in routinely and that you’re going to be doing the appropriate imaging and evaluations,” she continues.

Dr. Maturi reminds his fellow ophthalmologists of the longevity of diabetes. “Even though Protocol W (for example) was a four-year study, diabetes is not a four-year disease. Diabetes is a lifetime disease and it’s likely the next 30 to 40 years for that patient,” says Dr. Maturi. “We’ve done a great job with clinical medicine to increase diabetics’ lifespan, and the disease in the eye is not going away on its own.”

Dr. Maturi is a consultant for Allegro, Allergan, Allgenesis, Eli Lilly, Dutch Ophthalmic, Novartis, neurotech and Jaeb Center for Health Research. He receives research support from Allergan, Genentech, Ophthea, Kalvista, Samsung Bioepies, Graybug, Santen, Thromobgenics, Gyroscope, Gemini, Boehringer Ingelheim, Allegro, Senju, Ribomic, NGM biopharmaceuticals, Unity, Graybug and Clearside. He’s also the Safety Committee Chair of Aiviv. Dr. Pieramici receives research funding from and consults for Genentech, Inc. and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Sun discloses research support from Adaptive Sensory Technologies, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Optovue, Physical Sciences, Inc. and Genentech/Roche.

1. Writing Committee for the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network; Gross JG, Glassman AR, Jampol LM, Inusah S, Aiello LP, Antoszyk AN, Baker CW, Berger BB, Bressler NM, Browning D, Elman MJ, Ferris FL 3rd, Friedman SM, Marcus DM, Melia M, Stockdale CR, Sun JK, Beck RW. Panretinal photocoagulation vs intravitreous ranibizumab for proliferative diabetic retinopathy: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015;24;314:20:2137-2146.

2. Gross JG, Glassman AR, Liu D, Sun JK, Antoszyk AN, Baker CW, Bressler NM, Elman MJ, Ferris FL 3rd, Gardner TW, Jampol LM, Martin DF, Melia M, Stockdale CR, Beck RW; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Five-year outcomes of panretinal photocoagulation vs intravitreous ranibizumab for proliferative diabetic retinopathy: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol 2018;1;136:10:1138-1148.

3. Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network; Elman MJ, Aiello LP, Beck RW, Bressler NM, Bressler SB, Edwards AR, Ferris FL 3rd, Friedman SM, Glassman AR, Miller KM, Scott IU, Stockdale CR, Sun JK. Randomized trial evaluating ranibizumab plus prompt or deferred laser or triamcinolone plus prompt laser for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2010;117:6:1064-1077.e35.

4. Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network; Wells JA, Glassman AR, Ayala AR, Jampol LM, Aiello LP, Antoszyk AN, Arnold-Bush B, Baker CW, Bressler NM, Browning DJ, Elman MJ, Ferris FL, Friedman SM, Melia M, Pieramici DJ, Sun JK, Beck RW. Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. N Engl J Med 2015;26;372:13:1193-203.

5. Jhaveri CD, Glassman AR, Ferris FL 3rd, Liu D, Maguire MG, Allen JB, Baker CW, Browning D, Cunningham MA, Friedman SM, Jampol LM, Marcus DM, Martin DF, Preston CM, Stockdale CR, Sun JK; DRCR Retina Network. Aflibercept monotherapy or bevacizumab first for diabetic macular edema. N Engl J Med 2022;25;387:8:692-703.

6. Baker CW, Glassman AR, Beaulieu WT, et al. Effect of initial management with aflibercept vs laser photocoagulation vs observation on vision loss among patients with diabetic macular edema involving the center of the macula and good visual acuity: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019;321:1880-1894.

7. Maturi RK, Glassman AR, Josic K, et al. Four-year visual outcomes in the Protocol W randomized trial of intravitreous aflibercept for prevention of vision-threatening complications of diabetic retinopathy. JAMA 2023;329:5:376-385.

8. Brown DM, Wykoff CC, Boyer D, et al. Evaluation of intravitreal aflibercept for the treatment of severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy: Results from the PANORAMA randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol 2021;139:9:946–955.