Uveitis is characterized by significant, sight-threatening intraocular

inflammation that typically involves the uveal tract. Inflammation of

adjacent tissues can also develop, with associated morbidity. Because

uveitis can be associated with many conditions, patients are often

initially misdiagnosed.

In some cases, patients will present to the emergency room with a red, painful eye and will be diagnosed with conjunctivitis. They will be put on topical Tobradex (tobramycin/ dexamethasone). When they don’t get better, they will then be referred to an optometrist or an ophthalmologist.

Understanding Uveitis

Understanding Uveitis There are numerous causes of uveitis, including infectious agents or autoimmunity. In some cases, it may be part of a systemic disease process, such as juvenile inflammatory arthritis, sarcoidosis, or Behçet’s disease; or it may be associated with the HLA-B27-positive group of diseases.Infectious agents are also well-known causes, and these include the herpes group of viruses, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Toxoplasma gondii, and Treponema pallidum.

Most uveitis patients are between the ages of 10 and 50, and the condition can affect one or both eyes.There are four anatomic types of uveitis: anterior; posterior; intermediate; and panuveitis.

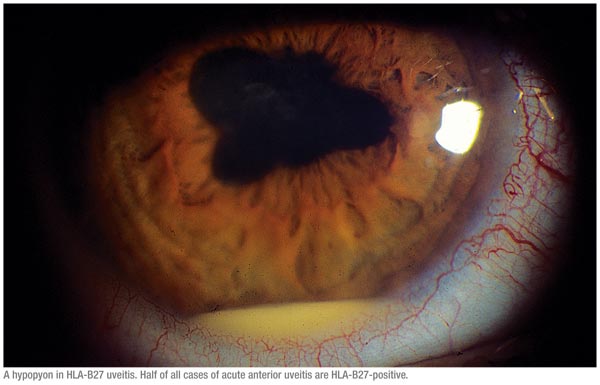

Anterior uveitis is the most common type of uveitis that we see. It typically presents acutely with pain, light sensitivity, and redness. It can be associated with diseases such as ankylosing spondylitis or juvenile inflammatory arthritis, or it can be idiopathic. Half of all cases of acute anterior uveitis are HLA-B27-positive.1 Approximately 50 percent of all patients with HLA-B27 acute anterior uveitis develop an associated seronegative arthritis, whereas only 25 percent of patients diagnosed with HLA-B27 seronegative arthritis develop acute anterior uveitis.

Posterior uveitis is inflammation of the choroid, retina and optic nerve. This type accounts for 15 percent to 22 percent of uveitis cases. It is typically chronic, recurrent and bilateral. The most common cause of posterior uveitis is infection caused by toxoplasmosis.

Intermediate uveitis is inflammation of the ciliary body and iris with spillover into the anterior chamber and the vitreous. It is less common but is one of the types of uveitis frequently referred to and managed by uveitis specialists. It has also been called cyclitis, pars planitis or vitritis. In most cases, the cause is unknown. It is typically chronic, and symptoms include floaters and blurry vision.

Panuveitis is inflammation that affects the entire eye. This type of uveitis often causes severe vision loss, and patients typically have floaters and a significant decrease in vision.

Diagnosis and treatment of uveitis is important because the condition can cause permanent vision loss, and it can also be the first presenting symptom of a serious systemic illness.

Diagnosis

|

Sometimes, the history will point you to the fact that the patient has an autoimmune disease like lupus or ulcerative colitis. There is a standard algorithm that most uveitis specialists go through to come up with a differential diagnosis that is specific to the patient.

In addition to the standard visual acuity tests and slit-lamp examinations, ophthalmologists will also order lab tests such as optical coherence tomography and fluorescein angiography.

Treatment

Typically, topical corticosteroids are used to treat anterior uveitis. The strength and dosage of the steroid depends on the severity of the inflammation in the eye. In general, it is fine to start treatment with topical steroid drops before you get all the lab work back.

Vision loss in anterior uveitis can usually be prevented by early treatment.For acute anterior uveitis, topical corticosteroids and cycloplegic agents remain the standard treatment.1 If uveitis does not respond to topical treatment, the next step may be a periocular steroid injection, or we can prescribe a short course of oral steroids.

Agents such as methotrexate are effective in reducing the incidence of recurrent attacks, and biological agents such as anti-TNF and anti-CD20 therapy may be effective in refractory severe anterior uveitis, but are rarely required.1 As you know, anterior uveitis can cause increased intraocular pressure.If this occurs, an IOP-lowering medication may also be prescribed.

For patients with intermediate or posterior uveitis, it is important to

identify the underlying cause, because if the cause is infectious, an

anti-infective agent is needed. For noninfectious causes, corticosteroids

can be used. If only one eye is affected, we may try injecting a steroid

into the eye. If the eye does not respond to treatment or there is

bilateral involvement, oral steroids may be prescribed.

For patients with intermediate or posterior uveitis, it is important to

identify the underlying cause, because if the cause is infectious, an

anti-infective agent is needed. For noninfectious causes, corticosteroids

can be used. If only one eye is affected, we may try injecting a steroid

into the eye. If the eye does not respond to treatment or there is

bilateral involvement, oral steroids may be prescribed.

However, it is well-known that the long-term use of high-dose oral steroids should be avoided due to their side-effect profile. As you know, side effects can include nausea, heartburn, weight gain and fluid retention, mood changes, high blood pressure, diabetes, osteoporosis, bruising, cataracts, elevated IOP, increased risk of infection, skin capillary fragility and heart problems.

One of my patients developed acute psychosis from high-dose, oral steroid use. Additionally, because of the risk of osteoporosis and because many uveitis patients are 20- to 30-year-old women, long-term steroid use should be avoided, and the lowest effective dose of oral steroids should be used. The general approach now is to try to minimize how much oral steroid a patient is given at the beginning of the course. So, if only one eye requires treatment, we try to localize the steroid to the eye.

As mentioned earlier, uveitis may be related to autoimmune disorders, and, in these cases, immunosuppressant therapy can be added to steroid therapy to control the uveitis. A recent study conducted in Germany found that mycophenolate mofetil is effective and well-tolerated in the treatment of chronic noninfectious uveitis.2 This retrospective study included 60 uveitis patients who were treated with mycophenolate mofetil with a follow-up period of at least five years. Of the 60 patients, 43 achieved control of intraocular inflammation, which was defined as inactive disease under a prednisolone dose of 10 mg or less daily after one year of therapy, and 45 of 55 patients achieved control of ocular inflammation after two years of therapy. Forty-nine patients achieved improvement or stabilization of visual acuity, while 11 patients experienced worsening.

Most of the patients who have uveitis will need treatment for years and will require long-term follow-up. Some patients who have anterior iritis might only have a couple of flare-ups in a year, and those patients might be treated with topical drops and a periocular or intravitreal injection.In between flare-ups, we may only see the patient every six months. If a patient has a systemic condition like sarcoidosis, is on an immunosuppressant and is stable, we will see him or her every three months. We chose three months as the follow-up interval because, if patients are on systemic agents, they need to have their blood count and their liver panel checked at a minimum of every three months to make sure that they are tolerating the drug well.

According to a recent study, many patients with primary anterior uveitis will relapse.3 The study included 102 patients with a first episode of anterior uveitis who were seen within 90 days of their first uveitis onset and were followed for 165 person-years after experiencing remission of the first episode. Of the 102 patients, 62 had a recurrence of anterior uveitis, so the incidence of relapse was 24 percent per person-year. At 1.5 years after achieving remission, 61 percent were still in remission. Interestingly, younger adults had a significantly higher relapse rate than middle-aged adults. Due to the findings of this study, the authors recommend including an explicit plan for detecting and managing relapses in patients with primary anterior uveitis.

Many patients with chronic noninfectious posterior uveitis may benefit from an intravitreal drug implant. This treatment method can reduce or eliminate many of the side effects of oral steroids or systemic immunosuppressants by delivering drug directly to the back of the eye rather than systemically.

A randomized, controlled trial found that a fluocinolone acetonide intravitreal implant provides an alternative therapy for prolonged control of inflammation in noninfectious posterior uveitis.4 In this three-year, multicenter trial, 110 patients received a 0.59-mg fluocinolone acetonide implant. For these patients, uveitis recurrence was reduced from 62 percent during the one-year preimplantation period to 4 percent, 10 percent and 20 percent, during the one-, two-, and three-year postimplantation periods. Additionally, more implanted eyes than nonimplanted eyes had improved visual acuity. However, implanted eyes had higher incidences of IOP elevation (10 mmHg or more) than nonimplanted eyes, and 40 percent of implanted eyes underwent glaucoma surgery compared with only 2 percent of nonimplanted eyes.

A more recent study confirmed the finding that patients receiving fluocinolone acetonide implants have a significant increased risk of increased IOP that often requires glaucoma surgery.5 This study included 42 eyes of 35 patients who received implants between June 2001 and March 2009. Of the 42 eyes that received implants, 19 required glaucoma surgical intervention. IOP-lowering was achieved by surgery in 94 percent of eyes at six months, and there was an average two-line gain of visual acuity three years after fluocinolone implant placement for those patients who underwent IOP-lowering surgery.

Another newer, local delivery option is the dexamethasone implant called Ozurdex that is approved for use in uveitis. Careen Lowder, MD, PhD, and colleagues recently reported the outcome of a randomized, prospective study in patients with non-infectious, posterior uveitis.6 Eyes were randomized to a sham injection (n=76), a 0.35-mg (n=76) dexamethasone implant, or a 0.7- mg (n=77) dexamethasone implant. Nearly half of the patients treated with the 0.7-mg implant achieved a vitreous haze score of 0 over the 26-week study, and 90 percent had an improvement of at least one unit, indicating significant control of the inflammation. There was a significant improvement in best-corrected visual acuity in the 0.7-mg implant group compared to a sham injection. The effect is rapid and continues for six months. At 26 weeks, 16.9 percent of the patients treated with the 0.7-mg implant needed a topical drop for IOP control. None of the patients required filtering surgery. This intraocular implant has a shorter duration of activity, but appears to have fewer side effects.

It is important to keep in mind that there is no single treatment that works best in every situation. If a patient with sarcoidosis presents to five or six different uveitis specialists, those five or six doctors may use two or three different drugs as the initial drug.

When to Refer

If a patient presents to a general ophthalmologist’s office and has no lesions in the retina or choroid and inflammation only in the vitreous or the anterior chamber, these patients can be treated for several weeks to see if the uveitis will respond. If a general ophthalmologist puts a patient on his or her maximal treatment and does not see a response after two or three weeks, then the patient probably needs to be referred. If a patient has evidence of a retinal or choroidal lesion, early referral is probably a good option.

Dr. Callanan is in private practice at Texas Retina Associates in Arlington. He is also clinical associate professor at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School in Dallas. Contact him at 7150 Greenville Ave., Suite 400, Dallas, Texas 75231. Phone: (800) 695-6941; fax: (214) 369-9612; e-mail:

dcallanan@me.com.

1. Wakefield D, Chang JH, Amjadi S, Maconochie Z, Abu El-Asrar A, McCluskey P. What is new HLA-B27 acute anterior uveitis? Ocul

Immunol Inflamm 2011;19(2):139-144.

2. Doycheva D, Zierhut M, Blumenstock G, Stuebiger N, Deuter C. Long-term results of therapy with mycophenolate mofetil in chronic non-infectious uveitis. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2011 Jul 1. [Epub ahead of print]

3. Grunwald L, Newcomb CW, Daniel E, et al; Systemic Immunosuppressive Therapy for Eye Diseases Cohort Study. Risk of relapse in primary acute anterior uveitis. Ophthalmology 2011 June 14 [Epub ahead of print].

4. Callanan DG, Jaffe GJ, Martin DF, Pearson PA, Comstock TL. Treatment of posterior uveitis with a fl uocinolone acetonide implant: Three-year clinical trial results. Arch Ophthalmol 2008; 126:1191-1201.

5. Bollinger K, Kim J, Lowder CY, Kaiser PK, Smith SD. Intraocular pressure outcome of patients with fl uocinolone acetonide intravitreal implant for noninfectious uveitis. Ophthalmology 2011 Jun 6 [Epub ahead of print].

6. Lowder C, Belfort R, Lightman S, et al, for the Ozurdex HURON Study Group. Dexamethasone intravitreal implant for noninfectious intermediate or posterior uveitis. Arch Ophthalmol 2011;129:545-553