By 2050, it’s estimated there will be about 19 million people in the United States 85 years of age or older, and by 2024, as many as one out of every four drivers on the road may be over 65. Although being able to drive allows older people to maintain their independence and social life, unsafe drivers are a significant risk to themselves and to others. For that reason, how our patients’ deteriorating vision may contribute to potential driving problems is an important issue. Furthermore, there are legal ramifications for ophthalmologists: In many states, doctors are required to report drivers suffering from visual limitations to the state’s Department of Motor Vehicles.

Glaucoma’s Impact on Driving

The evidence shows pretty clearly that glaucoma can undercut driving skill and increase a person’s chances of having an accident. One 2008 study compared the skills of 20 glaucoma patients and 20 age-matched controls in a 10-km on-road driving test with a trained instructor; the test was designed to check 55 standardized maneuvers and skills.1 The study found that glaucoma patients were six times more likely to need the instructor to apply the brake or use the steering override to prevent an accident, and the main reason for these problems was failure to see and yield to a pedestrian.

Another study done in Chicago compared the driving records of 40 glaucoma patients and 17 age-matched normally sighted controls.2 None of the controls reported having had any accidents in the preceding five years, but about 32 percent of the glaucoma patients reported having had accidents during that period. The study also compared the groups’ performance in driving simulators; in that setting the glaucoma patients were three times more likely to have an accident than the control subjects.

Other studies have found peripheral visual field loss to be associated with driving problems. One study involving 87 patients with visual field defects found that these subjects showed increased variability in lane position and more frequent lane boundary crossings than normally sighted individuals.3 Another study involving 28 drivers found that drivers with a more restricted binocular visual field had poorer anticipatory skills, as well as more difficulty matching the speed of other cars when changing lanes; maintaining lane position; staying in the lane when driving around a curve; and interacting with other cars on an interstate highway.4

Detecting a Driving Problem

One factor that can make detecting a driving problem challenging—for both the patient and the doctor—is that glaucoma produces gradual rather than sudden vision impairment. As a result, an individual may not initially notice that she’s having more difficulty driving. It may be a family member who notices that Dad can’t change lanes or parallel park the way he used to, or that his depth perception isn’t as good.

The problem may also not be immediately obvious to a doctor, because glaucomatous visual field loss may spare the central vision. A patient with advanced glaucoma may read a vision chart down to 20/25 or 20/30, which still qualifies her to drive, even though her visual field could be limited. Furthermore, when a patient presents for a cataract evaluation, driving vision almost always comes up; with glaucoma, the follow-up discussion is focused on compliance with the medication schedule, side effects of treatment, intraocular pressure and the results of any diagnostic tests. By the time those topics had been addressed, the allotted visit time is over and the subject of driving didn’t come up.

If the subject does come up, it may be in one of the following situations:

• The patient announces that he’s decided to stop driving. I’ve had a number of patients voluntarily tell me that they’ve stopped or limited their driving. They’ll say, “I just didn’t feel comfortable changing lanes any more,” or “I have trouble seeing at night,” or “I stopped driving on the interstate.” Many of these patients would meet the DMV criteria for driving, but limited themselves anyway. I tell them I understand com-pletely. (In some cases, their kids have taken the keys away from them.)

• A family member mentions the problem. For example, the patient may bring a driver because he has to be dilated for an exam. If the driver is the patient’s wife, she may comment that her husband seems to not see pedestrians crossing the street, until she points them out. That’s certainly a red flag to reassess the patient’s acuity and field in the context of driving ability. It may turn out that vision isn’t the problem; other factors, such as reaction time or arthritis in the neck may be involved. In that case, the primary-care physician would need to assess the patient. (Of course, if the patient doesn’t have to get dilated, he’ll drive himself and you may never know there’s a problem.)

• A patient with poor vision mentions that he’s still driving. Sometimes a patient with horrible visual fields talks about something that happened while he was driving to the exam. I’ll say, “You drove here? Based on your visual field you shouldn’t be driving—your peripheral visual field isn’t adequate to be a safe driver.”

Of course, if you have the opportunity, it’s a good idea to inquire about a vision-impaired patient’s driving status if—for example—he shows up at your practice without a driver. In that situation I may say, ”Who brought you in today?” If the patient says, “I drove myself,” I’ll pursue it. For starters, I’ll ask whether he’s driving both during the day and at night, and whether he stays on local streets or drives on the interstate.

Unfortunately, the reality is that most of us are seeing dozens of patients a day, and if the subject of driving doesn’t come up, we probably don’t bring it up. It’s easy for a problematic driver to slip through undetected.

|

|

|

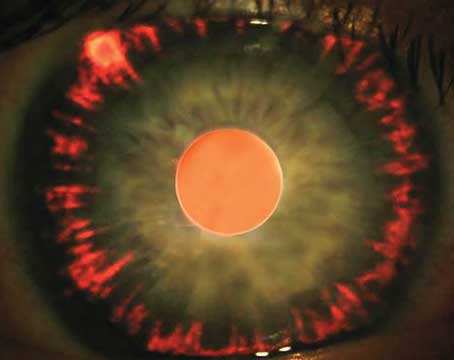

| Although this patient shows advanced visual field loss on the HVF 24-2 SITA-standard test, the binocular Esterman test (right) shows 110 degrees of horizontal field, so the patient does meet the minimum driving requirement in Pennsylvania.

(Image courtesy Eydie Miller-Ellis, MD) | ||

When you realize that a patient may be driving with a troublesome amount of visual loss, having objective information is very important. You may be required to recommend that his license be limited or suspended. Given the impact that this will have on the patient, you have to have solid, objective supporting evidence to make that recommendation.

When it comes to driving, peripheral vision is a big concern because a driver needs to be aware of his entire visual environment. He needs to be able to see cars coming from the side, particularly when changing lanes, and he needs to be able to see pedestrians. If peripheral vision has been limited by glaucoma, these abilities are diminished. If, in addition, he has slow reflexes or reduced cognitive ability, driving becomes even more dangerous.

Ideally, you should use a visual field test to objectively document the extent of the horizontal visual field. How wide the field needs to be to be considered safe for driving depends on the state in which you practice. In Pennsylvania, the horizontal visual field has to be at least 110 degrees in order for someone to qualify for a driver’s license.

One way to check this is to use manual (a.k.a. Goldmann) perimetry. Alternatively, the Humphrey visual field instrument can run a monocular or binocular Esterman test, which measures the horizontal and vertical extent of the patient’s visual field. The binocular test uses a 120-point grid that extends to 160 degrees temporally on both sides.

Of course, the visual field isn’t the only concern; visual acuity must also meet basic standards. Typically, every state’s Department of Motor Vehicles will specify visual acuity limitations for driving. For example, in most states if your best-corrected visual acuity is 20/40 or better, you can have an unrestricted driver’s license (as long as your visual field is adequate). If your vision is between 20/40 and 20/70, most states would restrict you from driving at night or on the interstate. If your combined vision is worse than 20/70, but better than 20/100, you’d have to go to the DMV and pass a road test to get a restricted driver’s license allowing daytime driving only, under 45 MPH—with no interstate driving.

|

| Moderate glaucomatous damage can spare central vision, making a loss of safe driving vision harder to detect. |

What is the doctor’s legal responsibility regarding a patient’s ability to drive safely? The rules vary from state to state. Pennsylvania requires physicians to report any patient 15 years of age or older who’s been diagnosed as having a condition that could impair his or her ability to safely operate a motor vehicle. If you fail to report such a patient you could potentially be held responsible as a proximate cause of an accident that results in death, injury or property loss. At the same time, if you do file a report, you’re immune from any civil or criminal liability. However, this is Pennsylvania law; laws may differ significantly in other states. You can determine your state’s requirements by visiting your state’s Department of Motor Vehicles website.

Some reporting requirements are common to all states. For example, all states require doctors to report a patient who has seizures, because you don’t want someone to have a seizure while driving. Most states also have general recommendations, but not mandates, for reporting vision deficits.

The other side of the legal question is: How will the patient react? In Pennsylvania, where you’re required to report drivers with very limited vision, you can’t be sued for violating a patient’s privacy, because you’re legally required to report him. If you’re practicing in a state that doesn’t require you to report unsafe drivers, it’s conceivable that a patient could try to sue you for reporting him. I know of one doctor who was threatened with a lawsuit for attempting to report a patient in a state that didn’t require it. (Of course, the way a patient reacts to the news will be strongly affected by how you deliver the message. For more on that, see below.)

Naturally, reporting a patient involves filling out a form. There are forms that are strictly for vision issues, forms that cover both vision and medical issues, and forms for just medical concerns. A typical driving-ability form will have a section for vision and a section for general health concerns. The ophthalmologist or optometrist completes the vision portion of the form while the primary -care physician (or another doctor) fills out the portion that deals with reflexes and cognition.

Interestingly enough, so far I haven’t had to generate many of these forms myself. In most cases, the patient brings the form in because he wants to renew his license, and I end up filling it out. Sometimes the patient doesn’t realize he has a problem, and my reaction is, you’ve got to be kidding! In those cases I just note on the form that this individual should not be driving. Sometimes a patient will want to keep her license for identification purposes. In that case, I advise her to apply for a state-issued identification card from the DMV. Once the form is submitted, the state takes the next step, contacting the patient about what he needs to do, such as any further testing the state requires.

Breaking the News

Taking away someone’s right to drive is not a small thing, so the way you break the news can make the difference between a dismayed patient and an angry patient. Obviously you can’t just say, “Well look, you’re going blind, you need to stop driving. Okay, my next patient is here.” You have to sit down and talk to the patient.

Some patients will take the news badly. They’ll say, “How am I supposed to get around? I don’t have anybody to take me to the grocery store. If I can’t drive I might as well just die.” You have to sit the patient down and say, “I understand that driving has been a very important part of your life. But because of your vision, you really shouldn’t be driving any more. You not only put yourself at risk, you put other people at risk.” They’ll say, “I only drive around the corner to the store.” I’ll say, “Most accidents happen within a mile of your home. And you’d feel terrible if you hit a child playing in the street or on the sidewalk because you couldn’t see off to the side very well. It would be tragic.” If you put the problem in those terms, that usually makes the point quite effectively.

Once you’ve discussed the situation with the patient, talk to the patient’s family and then file your report. You should also point out to the patient and his family that you’re required by law to notify the state (assuming that’s true where you practice).

Typically, the patient will request some kind of test to prove this one way or the other. At that point I’d perform the Esterman test. Sometimes, a patient I don’t expect to pass the Esterman test does pass, probably because it uses a different program and a different test stimulus brightness than a standard visual field. If that happens, I tell the patient that although he meets the legal standard, he needs to be aware that the glaucoma is affecting his ability to see in the periphery, as well as possibly diminishing his reaction time and having other negative effects that could affect his driving. I let him know that he needs to be more careful.

In some situations, the possibility of losing a driver’s license can be used as a motivator for patients who are on the borderline visually and are noncompliant with their medications. I can say, “If you don’t take care of yourself in regards to your glaucoma, your vision will get worse and you won’t be able to drive anymore.” The possibility of losing their license will motivate some people to improve their adherence to their medical treatment plan.

Younger Patients and Driving

Of course, younger patients can develop glaucoma as well. Most of the young glaucoma patients I see have congenital glaucoma and are in their late teens or 20s. In theory, glaucoma’s impact on driving ability should also be an issue for these patients, but in my experience it’s not often a problem. For one thing, these individuals may have significant vision loss that precludes them from getting a drivers license to begin with. Luckily, we have a great public transportation system here in the Philadelphia area, so it’s not a huge hardship for young people to get around without a car. So far, I haven’t encountered anyone in his 20s or 30s who was driving and shouldn’t have been.

I have had one or two patients with vision in the 20/40 to 20/60 range who were applying for their first license. I worked with them to provide evidence that they were eligible for driver’s education and, potentially, a restricted driver’s license. In this situation, I try to act as the patient’s advocate so he or she can get at least some driving certification.

Resources

Patients with borderline vision do have alternatives. Most rehabilitation centers have driver training programs, particularly centers that deal with people who’ve had strokes and other injuries. The cost to the patient is typically $150 to $200. If the patient passes the program, that might allow him to get a limited driver’s license. If you need help locating resources such as these, you can try contacting your DMV or local rehabilitation centers, search via the Internet or contact AARP for help locating resources for older drivers.

For the doctor, an excellent resource is the American Medical Association Physicians’ Guide to Assessing and Counseling Older

Drivers. It’s an extensive, compre-hensive document that can be accessed online at

nhtsa.gov/people/injury/olddrive/physician_guide/PhysiciansGuide.pdf. It discusses:

- safety issues surrounding older drivers with functional or medical impairment;

- how to tell if a patient is at risk for unsafe driving by looking at certain red flags;

- assessing visual ability;

- finding driver rehabilitation specialists;

- counseling patients who shouldn’t be driving any more; and

- ethical and legal physician responsibility.

The guide is a great resource for physicians, and I believe any glaucoma doctor would benefit from at least scanning through it.

Dr. Miller-Ellis is a professor of clinical ophthalmology and director of the Glaucoma Service at the Scheie Eye Institute of the University of Pennsylvania Health System.

1. Haymes SA et al. Glaucoma and On-Road Driving Performance. IOVS. 2008;49:3035-3041.

2. Szlyk, Janet, et al, Driving performance of glaucoma patients

correlates with peripheral visual field loss. J Glaucoma 2005;

14:2:145-150 .

3. Coeckelbergh TRM. The Effect of Visual Field Defects on Driv-ing Performance. A Driving Simulator Study. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120:1509-1516.

4. Bowers A et al. On-Road Driving with Moderate Visual Field Loss. Optometry and Vision Science 2005;82:8:657-667.