For your patient who’s progressed to pigmentary glaucoma, and medical therapy isn’t enough, you’ve got to start thinking about your laser options. However, there aren’t a lot of large, randomized trials to guide you. Here, glaucoma experts review their approaches to dealing with these patients.

The Laser Options

The treatment of pigmentary glaucoma involves lowering eye pressure using medications, laser or (for intractable cases) surgery. Ophthalmologists’ current laser options consist of peripheral iridotomy, which proponents say stops the disease process, and selective laser trabeculoplasty, which is used to quickly lower pressure.

According to Robert J. Noecker, MD, in practice in Fairfield, Connecticut, laser treatment for pigmentary glaucoma is very useful and probably needs to be considered in all patients with this condition. “Laser treatment works best earlier in the disease process,” he says. “It’s good to be proactive and stop the pigment dispersion before it causes too much damage. Pigmentary glaucoma tends to occur in a younger population of glaucoma patients—the average age is 30 or 40 years. These patients have extreme pressure and tend not to tolerate medications as well as older patients do, so laser therapy is very useful in this subtype of glaucoma.”

Peripheral Iridotomy

Patients with pigmentary glaucoma have an abnormal iris. The iris is concave, which leads to pigment dispersion off the back of the iris from contact between the zonules and ciliary body.

“One way to change this anatomical configuration is to use pilocarpine,” Dr. Noecker says. “An alternative is laser iridotomy, which equalizes the pressure between the anterior and posterior chambers, allowing the iris to resume a more normal shape. These patients have a reverse pupillary block, so the pressure in the anterior chamber gets higher than in the posterior chamber, which pushes the floppy iris posteriorly. This chafes the pigment off, which is toxic to the trabecular meshwork. The procedure is the same as for angle-closure patients, but the endpoint is different. We want the anterior chamber to actually shallow a little bit.

“The effect it has on eye pressure is a bit unclear, but I don’t think it’s ever a bad thing to do,” he adds. “However, in my practice, I’ve seen the most benefit in preventing the eye pressure from going up. So, I think it works well before the trabecular meshwork is so damaged that there’s no positive effect on the eye pressure. Iridotomies are good at stopping the underlying disease process, but the effect on eye pressure is unclear and a little bit unpredictable. I look at it as more of a tool to stop the pigment dispersion.”

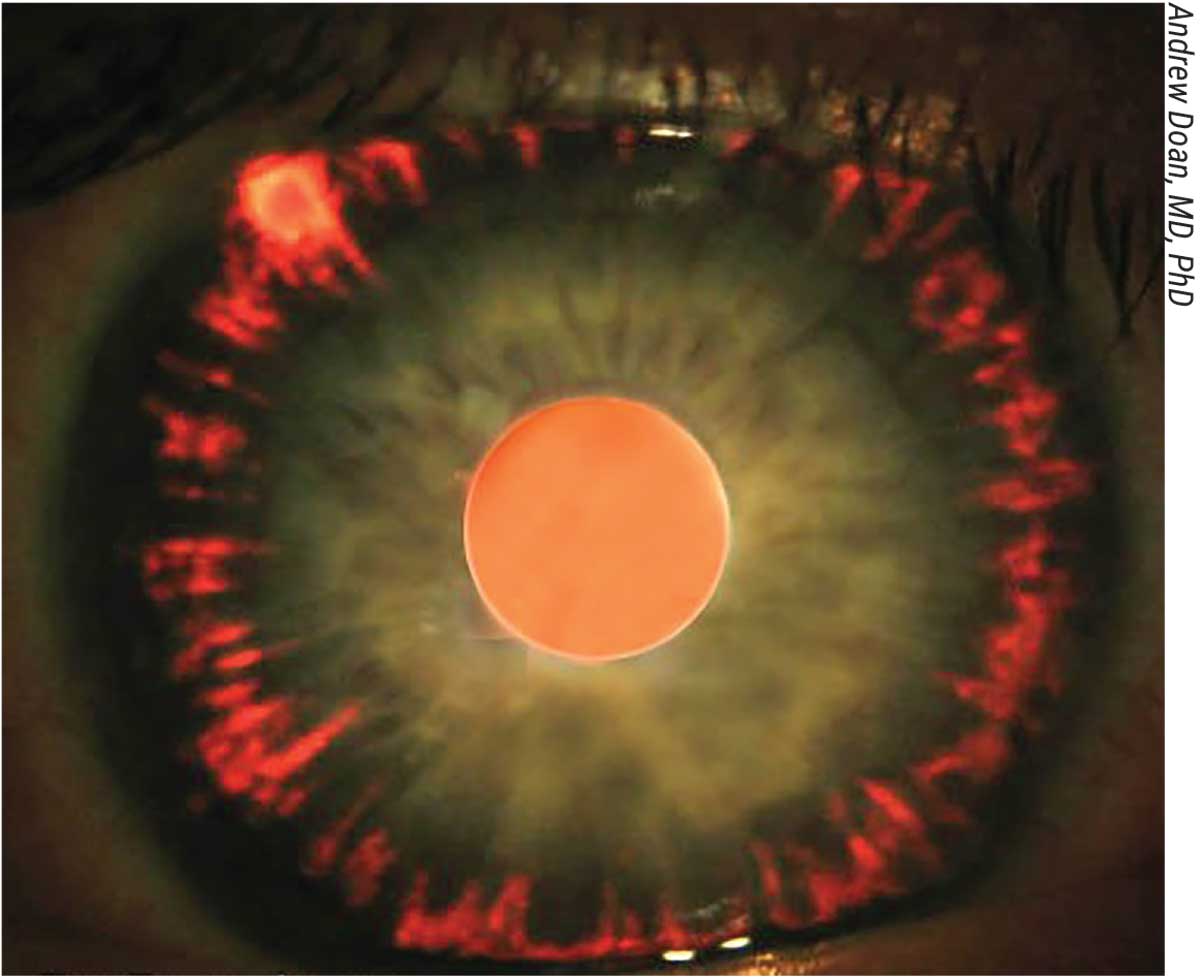

|

| Iris transillumination defects in a radial pattern in pigment dispersion (backbowing of the iris causes it to rub on the lens zonules). |

According to Michael Stiles, MD, who is in practice in Overland Park, Kansas, there’s been debate for some time as to whether iridotomy changes the course of the disease and whether there’s improvement in long-term pressure control or visual field preservation. “There’s no strong evidence that it’s successful in improving the course of the disease,” he says. “However, on gonioscopy some patients clearly have a reverse pupillary block to their iris configuration. And, in those patients, I will at least discuss it with them. In a handful of patients, I’ve used iridotomy to try to reduce the amount of pigment dispersion that occurs throughout their lifetime. There’s just not enough strong evidence to do it on every patient, particularly those who have an average-looking angle.

“If a patient doesn’t have a reverse pupillary block configuration, I wouldn’t recommend an iridotomy,” Dr. Stiles adds. “Additionally, if a patient has an IOP that’s grossly out of control, there’s the potential for an intractable pressure spike with any type of laser procedure.”

Montreal’s Paul Harasymowycz, MD, agrees that it should only be considered in certain patients. “It’s not something that’s commonly performed,” he argues. “However, I would consider performing an iridotomy, for instance, in someone who is a young athlete with pigment dispersion who has what we call the ‘pigment storm.’ This occurs after performing some kind of exercise where there’s movement that releases tons of pigment. These patients will have symptoms of a whitening of their vision. With the sudden release of pigment, patients get an extremely high pressure, and those kind of pressure spikes may cause optic nerve damage.”

He doesn’t typically perform iridotomies on older patients. “Older patients typically don’t have as much pigment, and it’s an unnecessary procedure in patients who will soon undergo cataract surgery,” he explains. “Physicians should be cautious about performing iridotomy in patients with a moderate degree of myopia. In pigment dispersion, there’s an association with having lattice dystrophy of the peripheral retina. To perform iridotomy, we often use pilocarpine to constrict the pupil. In these cases, if we give pilocarpine, there’s the potential that it could pull on the peripheral retina and cause a tear. In cases of laser iridotomy in pigment dispersion, I perform it by constricting the contralateral pupil with bright light.”

A recent literature review found insufficient evidence to justify the use of peripheral iridotomy for pigmentary glaucoma or pigment dispersion syndrome.1 Although adverse events associated with peripheral iridotomy may be minimal, the long-term effects on visual function and other patient-important outcomes haven’t been established.

The literature review included five randomized controlled trials that included 260 eyes of 195 patients comparing YAG laser iridotomy to no laser iridotomy. Three trials included participants with pigmentary glaucoma at baseline, and two trials included participants with pigment dispersion syndrome. At an average follow-up of 28 months, the risk of progression of visual field damage was uncertain when comparing laser iridotomy with no iridotomy.

One trial reported the mean change in IOP in eyes with pigmentary glaucoma. At an average of nine months of follow-up, the mean difference in IOP between groups was 2.69 mmHg less in the laser iridotomy group than in the control group. In this same trial, there was no meaningful difference between groups in terms of the mean change in anterior chamber depth at an average of nine months of follow-up. (No other trial reported mean change in anterior chamber depth.)

Two trials reported greater flattening of iris configuration in the laser iridotomy group than in the control group among eyes with pigmentary glaucoma; however, investigators provided insufficient data for analysis. None of the trials reported data related to mean visual acuity, aqueous melanin granules, costs or quality of life outcomes. Two trials assessed the need for additional treatment for control of IOP. One trial that enrolled participants with pigmentary glaucoma reported that more eyes in the laser iridotomy group required additional treatment between six and 23 months of follow-up than eyes in the control group.

SLT

Reviewing SLT’s mechanism of action, Dr. Noecker says its direct treatment of the trabecular meshwork induces a low-grade inflammatory response which, in turn, activates chemical mediators and recruits monocytes so that the TM is cleared of debris.

“In pigmentary glaucoma patients, it’s appropriate to perform SLT, but we must recognize that this population is at a higher risk for complications from it,” Dr. Noecker says. “It’s important to note, however, that SLT is one of the safest glaucoma therapies. It’s as benign as it gets, but the pigmentary glaucoma population has a higher risk of experiencing IOP spikes for two main reasons: One is that they have a lot of pigment, which equals more laser energy absorption. The second is that the pigment that exists in the trabecular meshwork is outside of the cells. We’re trying to target the trabecular meshwork cells, but pigmentary patients have a coating of pigment hanging out on the surface of these cells. That absorbs more of the laser, so you get a lot of laser energy absorption, but you don’t get the beneficial therapeutic effect. Therefore, when we perform SLT, instead of doing 360 degrees, we typically do 180 degrees maximum, maybe in increments of 90 degrees. It’s baby steps versus using as much as you can to get to the point.”

Dr. Stiles agrees. “The more pigment in the angle, the less energy should be used, because it doesn’t take much energy to produce a visible reaction in the angle with each application,” he says. “So, in these patients, I may treat only 180 degrees instead of the full 360 and keep the power low. I also watch the patient more carefully for the first hour after the procedure to make sure he or she doesn’t have a pressure spike. Because these patients are typically younger, their lenses are clear, so phaco-MIGS is probably not a realistic option. SLT can be very helpful in reducing medication burden and avoiding incisional surgery.”

Interestingly, Dr. Harasymowycz had a series of patients who developed a large pressure spike after SLT.2 All four glaucoma patients in this series presented with post-SLT IOP elevations. Three had features of pigmentary dispersion syndrome, and the fourth had a heavily pigmented trabecular meshwork. Two patients had previous argon laser trabeculoplasty in the same eye in which SLT was performed, and one had previous ocular trauma.

“The pressure was so high that three of them had to go on to urgent trabeculectomy,” recalls Dr. Harasymowycz. “So, you should be very judicious in the number of spots, and I usually would lower the energy quite significantly. A typical SLT energy setting for the laser would be between 0.8 and 1.2 mJ. However, in pigment dispersion, I would typically use 0.4 to 0.6 mJ, and instead of doing 50 to 60 applications over 360 degrees, which would be my technique in someone without pigment dispersion, I would probably do 25 to 30 applications and consider only doing 180 degrees. And those patients should be followed.

“These patients need to have their pressure checked 45 minutes to an hour after performing SLT because often they’ll be prone to developing pressure spikes,” he adds. “If you see that the pressure is rising, you may want to keep them on oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitors for a few days after performing the SLT. In our series of patients, there was a direct correlation between the amount of pigment seen in the angle and the propensity to develop a pressure spike.”

Unfortunately, the long-term effects of SLT in pigmentary glaucoma when eyes are treated over 180 degrees seem to be low.3 In a recent retrospective chart review, researchers assessed the long-term efficacy of SLT treatment in patients suffering from pigmentary glaucoma. The primary outcome measure was time to failure after SLT treatment. Failure was defined as any of the following: less than 20 percent IOP reduction; change in the medical treatment; performance of a further SLT treatment; and the patient being sent for surgery. All patients were treated over 180 degrees with SLT. The study included 30 eyes in 30 patients, and the average time to failure after SLT was 27.4 months. The success rate was 85 percent after 12 months, 67 percent after 24 months, 44 percent after 36 months, and 14 percent after 48 months.

Interestingly, because they have different goals, SLT and peripheral iridotomy procedures can be performed in combination.

In a small study from Europe, researchers performed a two-stage PI/SLT treatment on 12 patients (22 eyes) with pigmentary glaucoma. Their average IOP was 19.94 ±0.94 mmHg. The first stage consisted of a laser iridotomy, followed by SLT an average of 5.5 ±2.2 months later. The follow-up was 16.8 ±3.2 months.

In the early postop period after the laser iridotomy, the average IOP decreased to 14.76 ±0.72 mmHg, but increased at later follow-up. After SLT, the researchers say there was a decrease to 12.39 ±0.66 mmHg. There was also a significant decrease in the number of hypotensive medications used, from 1.73 ±0.18 preop to 0.86 ±0.15 afterward.

Putting the combination strategy into context, Dr. Stiles says that iridotomy is “more for long-term reduction of pigment dispersion and pressure control, and SLT is more for immediate pressure reduction.”

Dr. Noecker is a consultant to Quantel and Iridex. Drs. Stiles and Harasymowycz have no financial interests to disclose.

1. Michelessi M, Lindsley K. Peripheral iridotomy for pigmentary glaucoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;2:2:DC005655.

2. Harasymowycz PJ, Papamatheakis DG, Latina M, et al. Selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) complicated by intraocular pressure elevation in eyes with heavily pigmented trabecular meshworks. Am J Ophthalmol 2005;139:6:1110-1113.

3. Ayala M. Long-term outcomes of selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) treatment in pigmentary glaucoma patients. J Glaucoma 2014;23:9:616-619.