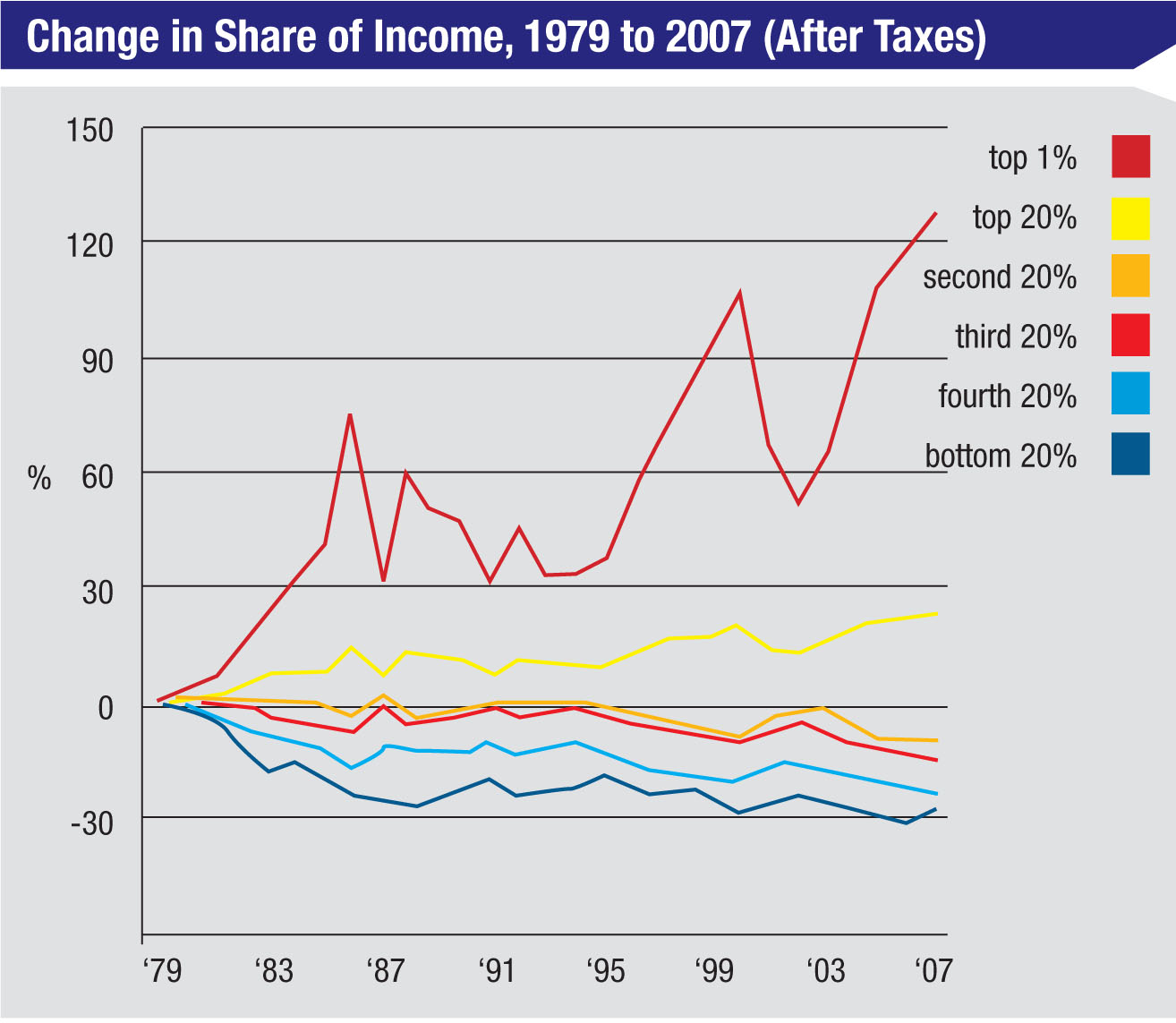

While the gap between rich and poor in America widens and new technologies become ever more expensive, Medicare reimbursements continue to shrink. The result is a perfect storm of economic challenges for ophthalmologists.

In the midst of this, much discussion has focused on the pros and cons of alternative practice models. Those alternatives include creating a two-tiered practice that provides complex services to high-end, self-pay patients, while offering basic services to low-end, pay-by-insurance patients. Other possibilities include dropping insurance patients altogether to focus solely on patients who want high-end service, or opting out of insurance but still offering both high- and low-level service.

Here, surgeons share some of their experiences with these and other practice variations, to help shed light on the good and not-so-good points of each.

Different Levels of Service

The concept of a two-tiered cataract practice—in which patients of different means are treated to different levels of service—is not new. Given the vastly different economics of treating insurance-pay patients and self-pay patients, it’s not surprising that in many parts of the world those groups receive very different treatment when they visit the ophthalmologist for cataract surgery.

“The concept of a two-tiered eye-care system exists in other corners of the world, such as in the United Kingdom and in India,” observes Uday Devgan, MD, FACS, FRCS, chief of ophthalmology at Olive View UCLA Medical Center, associate clinical professor at the UCLA School of Medicine, and in private practice at Devgan Eye Surgery in Los Angeles. Dr. Devgan says he’s visited and learned from clinics in both countries.

“I visited a clinic in India where one side of the ophthalmology office was crowded, small and simple,” he says. “The other half of the office was larger, luxurious and upscale. It was more private, and patients had more choices and got more detailed exams—and they were happy to pay more to have these advantages. The upscale patients literally came in the front door, while the basic patients came in the back door. (The operating room was in the middle.) Sometimes the same surgeon treated both sets of patients; sometimes one surgeon managed the premium patients while a more junior or beginning surgeon helped the other patients.”

Dr. Devgan notes that in the U.K. it’s rare to find different levels of treatment in any one practice, but higher-end practices do exist and are available for those willing to pay for a higher level of care. “In the U.K., the National Health Service covers everyone, but 8 percent of patients still elect to be in the private sector, according to the British Medical Association,” he says. “There are challenges with the NHS system, which is part of the reason some patients would rather pay out of pocket.”

Dr. Devgan observes that the United States seems to be moving in the direction of the two-tiered practice. “Patients now can pay out of pocket for astigmatism correction with limbal relaxing incisions via a blade or the femtosecond laser, or for a presbyopia-correcting IOL,” he notes. “That wasn’t the case in the past. We’re now able to offer refractive surgical results at the time of cataract surgery, and this has a lot of value to many patients. Furthermore, technology like femtosecond lasers for cataract surgery forces the issue. Now you end up with patients who can pay for the technology and patients who can’t.

“The lofty goal is for everyone to get the very best treatment in a timely manner for a very low cost,” he adds. “But you can only have two of the three. If you want the best care and affordability, you may wait two years for surgery. If you want the best care right now, you’ll have to pay for it. If you want quick, affordable care, you won’t get the best quality. That’s the conundrum.”

Making Two Tiers Work

Providing two different levels of patient care can be done in a number of different ways, as is demonstrated by the cataract practices in India and the U.K. However, it’s rare to find anything in America that approaches the Indian system, where poor and wealthy patients have a completely different experience.

William L. Rich III, MD, medical director of health policy for the American Academy of Ophthalmology, says he’s skeptical that creating a two-tiered cataract practice that offers a different level of service to cash patients and insurance patients will ever become a popular format in America. “Cataract is the most successful operation performed in the United States—3.5 million surgeries a year—and the vast majority of those are Medicare,” he notes. “There’s no wait to get surgery beyond a week or two, and the outcomes don’t appear to be significantly better with technology such as the femtosecond laser, so even well-to-do patients know they can get good results without going outside insurance.

“The only way this could occur, outside of a real ‘carriage trade,’ is if all of the Obama health-care payment reform fails,” he adds. “Then there would be huge cuts in commercial and Medicare rates, on the order of 30 to 35 percent, which would probably drive doctors and patients into a two-tiered system.”

That doesn’t mean that other variations might not be feasible, however. Vance Thompson, MD, who practices at Vance Thompson Vision/Sanford Health in Sioux Falls, S.D., and is an assistant professor of ophthalmology at the University of South Dakota School of Medicine, considers his practice to be two-tiered, in that he offers higher-end options to patients who are willing to pay for them. But beyond that, the similarities to India or the U.K. end.

“Depending on the quarter, our practice is 30 to 40 percent premium implants and 60 to 70 percent traditional implants,” says Dr. Thompson. “The traditional implants are people who are very comfortable with a monofocal implant and wearing glasses postop.”

Dr. Thompson says he considers his practice to be two-tiered, in the sense that both premium and basic cataract patients are welcome. However, he says that all patients are essentially treated the same. “That includes the way we market and how we handle phone calls,” he notes. “The packet of information we send out talks about both arms of our cataract practice. Patients receive the same waiting room experience, and the same initial work-up and discussion.”

Dr. Thompson says the “fork in the road” between the two tiers occurs when patients are asked whether they’re OK with wearing glasses, or if they’d prefer to be able to do many activities without glasses. “If the patient is fine with wearing glasses, we typically implant an aspheric monofocal IOL, most likely using a traditional phaco technique, unless we encounter a special circumstance in which we feel femtosecond laser technology would be better for the patient,” he says.

“We primarily use the laser for the patients who are interested in an accommodative or multifocal implant, or a toric lens,” he continues. “These patients receive extensive diagnostics, to ensure, for example, that if the patient needs a refractive enhancement postop he’ll be a good candidate for that procedure. They receive a full corneal refractive analysis and a full lenticular refractive analysis, and we use the ORange device from WaveTec to perform intraoperative aberrometry to compensate for shifts in effective lens position. We call this protocol Advanced Diagnostics. It includes any refractive enhancement that may be required postoperatively.”

Dr. Thompson is quick to note that the division between the two tiers does not include providing basic patients with fewer amenities or treating them with less respect. “We don’t have a fancy side of the office for the people who pay more,” he says. “We want pillow-under-your-feet service for both groups of patients.” He acknowledges that in some parts of the world, patients who pay more for higher-level service are treated differently. “I want no part of that,” he says. “I want to treat everyone equally well. We can afford to do that, and it’s the right way to treat people. I think most patients in this country appreciate that we do.”

Dr. Thompson adds that besides being the right thing to do, this policy also benefits the practice. “We work hard to create an exceptional patient experience,” he says. “We want our patients to say, ‘I don’t think I’ve ever been treated so well in a doctor’s office.’ Word of mouth is a powerful marketing tool when you treat everybody with great respect.”

Another variation on the two-tiered practice concept consists of providing your services at two different locations that serve different populations. “In a way, I’m doing a version of treating two tiers now,” observes Dr. Devgan. “Part of the week I’m at the county hospital, teaching the UCLA ophthalmology residents a wide spectrum of ocular surgery, from cataracts to glaucoma to trauma. The care there is often free or very low-cost, and we treat a large number of patients from all walks of life. The rest of the week I’m in my own private practice, focusing on cataract and refractive surgery. So I deal with two completely different populations, albeit at different locations.”

Pitfalls of a Two-Tiered Practice

Offering the higher-end, private-pay option is becoming more common, in part because American patients tend to like advanced technology, and in part because the greater income from private-pay patients is becoming more necessary in the current economic climate. But adding these options to a practice can entail a number of challenges:

• Splitting your focus undermines your marketing image. Creating a two-tiered practice can make it difficult to present a clear practice image to your local population, notes David D. Richardson, MD, medical director at

San Gabriel Valley Eye Associates in San Gabriel, Calif. “Compromises often cause more difficulty than just focusing on one extreme or the other,” he says. “In marketing, especially today, the successful businesses are the ones that focus on a niche, and do so in a way that engenders the loyalty and passion of the people in that niche. If you take the middle ground, trying to be fair to people at different ends of the spectrum, there’s no way you’ll engender the kind of passion, loyalty and customer testimonials that you’ll need to grow and survive.”

• Purchasing high-end technology to support premium patients is costly. “It’s expensive to provide the most sophisticated technology, and if the vast majority of your patients are Medicare patients, you may not be able to offer that option,” notes Dr. Thompson. “So if you hope to maintain both tiers, it becomes a business decision. You need a certain number of premium patients if you’re going to be able to support premium technology. In our practice we’ve had enough patients converting to advanced technology that we’ve been able to offer it for many years.”

• It’s difficult to manage two different sets of expectations. “I understand that many solo doctors are hoping to build in a safety net by serving more than one population, but compromising is false security as far as I’m concerned,” says Dr. Richardson. “I don’t believe you can effectively see 50 or 60 patients a day and also cater to those patients who are going to pay cash. The latter patients expect to get a certain value for their cash payment, which ultimately includes spending a certain amount of quality time with the doctor. That’s tough to accomplish if you also have to see a ridiculous number of patients per day to cover your overhead.

“Of course,” he adds, “there are exceptions. Some doctors make it work. However, I’d argue that those practices would do even better if they focused on one population or the other.”

• You’ll have to bring in new patients. Dr. Richardson notes that in order to successfully focus even a part of your practice on high-end patients you have to make sure your patient population can support it. “If you already have a loyal group of patients who are willing to pay for high-end services, and you don’t provide those services as much as you’d like because you’re too busy dealing with insurance and other poorly reimbursed activities, then it might make sense to go that route,” he says. “But if you don’t already have a core group of patients who fit that demographic, then you’re going to have to figure out how to bring those patients in.”

• Some doctors may perceive sharing overhead costs as unfair. “One of the issues with dividing a practice,” Dr. Richardson observes, “is that when a multi-doctor practice deals with both insurance patients and private-pay patients, if one doctor doesn’t accept insurance, that doctor is going to end up subsidizing the cost of handling the other doctors’ insurance paperwork. Managing insurance paperwork can cost more than $80,000 per doctor. So if one doctor goes all-cash, but shares the overhead with a segment of the practice that’s dealing with insurance, how beneficial is that for the all-cash doctor? He or she has to subsidize insurance collection to the tune of almost six figures. From that perspective, I think it makes more sense for the doctor who’s going to cash-only to just give the heave-ho to the bloated insurance overhead and structure.”

|

| The growing income gap between the wealthy and not-so-wealthy in America has produced two distinct possible markets for health services. (Source: Congressional Budget Office) |

“A similar arrangement would be necessary in a two-tiered practice, assuming different surgeons handle the two tiers, because the physician who’s going all-cash shouldn’t have to pay for all of the billing staff, billing consultants, software licensing and support—all of those insurance-related details that become more onerous every year,” he continues. “That issue would have to be resolved, perhaps over the first six months or year. If you couldn’t reach an equitable agreement, the two-tiered practice would probably end up cleaving into two separate practices.”

• Doctors don’t have business training. Dr. Richardson notes that doctors who want to practice in less-traditional ways are at a disadvantage before they leave the starting gate. “Doctors are not taught anything about marketing, sales, demographics or business,” he points out. “I think it’s a huge flaw in our collective medical education. We’re thrown into the practice of medicine with absolutely no business skills.”

• Patient demographics can be complex. “Understanding the demographics of the populations we treat isn’t as straightforward as many doctors assume,” Dr. Richardson points out. “To think of a practice as being positioned for a wealthy population or poorer population—or for both, in the case of a two-tiered practice—is simplistic and naïve in our modern society. You can slice up the baby boomers into half a dozen different demographic segments, each one with a completely different set of buying habits and values. And if you talk about catering to the rich, which rich are you talking about? The wealthy members of different generations have very different values and buying habits. So you have to consider far more than just the financial status of your local population to know whether you’ll have enough support for the type of services you plan to offer. A significant amount of research needs to be done for a practice to make any of these decisions.”

Moving to Cash Only

Another way to respond to declining Medicare reimbursements (and, perhaps, to the large number of restrictions and regulations that accompanying participating in the program) is to drop out of the Medicare system altogether and only accept private-pay patients. This is not an easy thing to accomplish successfully; a number of well-known surgeons have been unable to stay afloat without rejoining Medicare.

One issue that arises when planning to drop Medicare is whether you want to appeal only to wealthier patients, or to take all comers, including existing patients who are motivated to stay with you but have no interest in paying for advanced intraocular lenses or femtosecond laser surgery. Dr. Richardson is planning on opting out of the system soon, and he falls into the latter category.

“My current primary practice demographic is about 70 percent fixed-income Medicare patients,” says Dr. Richardson. “Most of them are not wealthy.” Although this might seem like a risky situation in which to convert to an all-cash practice, Dr. Richardson says that in his experience, wealthy patients are the least likely to pay cash for covered services anyway. “Wealthy patients are most likely to view doctors as commodities,” he says. “They have no problem pulling out a checkbook and paying $3,000 or $4,000 for a blepharoplasty, but when it comes to paying a $35 copay, it’s my wealthy patients who complain the most. So my practice will not be a boutique or concierge practice. My fee schedule is going to be set up in such a way that I’m hoping most of my patients will be able to afford to continue seeing me.

“I mention to my patients that my great uncle practiced during the Great Depression, when people were far worse off then than they are now,” he continues. “Many of my great uncle’s patients couldn’t pay in cash, so he ended up getting paid in chickens and pigs. I don’t expect modern patients to barter like that, but if I have a certain fee and a patient can’t afford that fee, I know that for the most part they’ll try to pay what they can—especially the older patients from the ‘greatest generation.’ And that’s acceptable to me.”

Dr. Thompson, who serves both self-pay and insurance-pay patients, sees an important advantage to not restricting a practice solely to patients who will want the high-end options. “Many patients don’t actually know what they want when they come in,” he observes. “A lot of them come in thinking that they don’t want the advanced technology, but after we educate them about it, they say, ‘I want that!’ And it’s impossible to guess which ones will be interested. If you just send out a packet of information about the advanced technology and expect the premium patients to come in, you’re going to be missing out on a lot of patients. You need some mechanism to attract both groups.”

When It’s Time to Opt Out

“The reality is, nobody has much experience with transitioning out of Medicare,” says Dr. Richardson. “There are lots of consultants to advise us on how to bill, create a compliance plan, sell our practices or bring in a new associate. But these are uncharted waters.”

Nevertheless, more and more surgeons are considering opting out. If you decide the time has come, these strategies may help:

• Consider changing slowly. Dr. Richardson notes that a bigger change carries bigger risks. “Doctors in general are risk-averse, and you can make the argument that changing a practice as little as possible is beneficial,” he says. “So it may make sense for a doctor in a multi-doctor practice who is switching to all cash to take the yearly $80,000 overhead hit, at least for the first couple of years. That way his patients don’t have to get used to a new office, new staff and so forth. In general, if you can make the transition for your patients as easy as possible, they’re more likely to stay with you. At least that’s my impression from seeing several practice transitions in my local area.”

• Choose your explanation to patients carefully. Dr. Richardson notes that the way you explain your decision to make the transition will affect how your patients react. “If your explanation for dropping Medicare is very focused on the declining fees, you won’t get any empathy from your patients,” he points out. “Patients do, however, appreciate that the sheer administrative hassle of dealing with Medicare and insurance companies is becoming overwhelming for solo practitioners.”

• Consider time-sharing your office. Dr. Richardson has come up with some creative ways to increase the chances that his upcoming Medicare-free practice will do well. “In order to cut my overhead, I’m renegotiating my lease,” he explains. “I’m going to be time-sharing my office. That will allow me to stay at the same location and keep my staff. We’ll probably end up flex-timing, and I’ll only be there half the time I’m in the office now. That’s probably all I’ll need to be there, since I expect to lose 50 percent of my patients.

“Meanwhile,” he continues, “another doctor who does accept Medicare will be working in my office on the days that I’m not there. He’s a member of a large group with a lot of administrative support, so they can tolerate the administrative hassle. And I won’t have to cover any of the bloated overhead that comes with insurance billing.

“What I believe will happen is that those patients who are unable or unwilling to see me as all-cash patients will most likely end up coming to the same office to see the other physician, even though he’s not part of my practice,” he says. “That should help to make the transition for my patients very smooth. If they want to continue to see me, the only thing that will change is that they’ll have to pay me for my services.”

• Look long and hard before you leap. “There’s a lot of preparation that has to be done to see whether or not a practice can successfully make the transition into an all-cash practice,” says Dr. Richardson. “The risks involved are great, so any practice that’s considering doing this should be prepared to spend time and money on research—not just bringing in a consultant, but running the financial projections, surveying current patients, and figuring out how you’re going to bring in more patients, because you’re going to lose a certain number of patients that you have, even among those with high loyalty to your practice. Some of those patients simply won’t be able to afford to pay cash, even if you keep your fees reasonable.

|

| Providing premium products and services usually requires a more extensive diagnostic work-up—which in turn requires that the practice purchase more expensive instrumentation.

(Image courtesy Vance Thompson, MD) |

• Talk to other doctors who’ve already been there. Although there are not a large number of ophthalmologists who have successfully made the transition to all-cash practices, Dr. Richardson notes that doctors who’ve made the transition in other areas of medicine such as orthopedics can be helpful. “In many ways, orthopedics is similar to ophthalmology,” he points out. “It’s a high-volume, largely Medicare surgical subspecialty. The orthopedic doctors I’ve spoken to who have made this type of transition have been very helpful in preparing me to avoid as many stumbling blocks as possible.”

• High satisfaction scores are not sufficient. “I’ve been doing internal questionnaires among my own patients, looking at loyalty scores,” says Dr. Richardson. “Loyalty scores are different from satisfaction scores when you’re making a change like this. For example, you may have surveys that show that your patients are very satisfied with your practice, but that won’t tell you how many patients will stay with your practice. You need a loyalty survey, such as the “ultimate question” survey, which divides patients into enthusiastic ‘promoters,’ passive patients who are satisfied but can easily be wooed away and unhappy ‘detractors.’ ”

• Practicing in a wealthy area is not sufficient. “Some brilliant surgeons have opted out of the system and been unable to make it work,” Dr. Richardson points out. “Practicing in a very wealthy area, for example, may not be enough. Just because people have the ability to pay does not mean they will pay. Furthermore, wealthy areas are often packed with competing practices.

“As doctors, many of us have a strong sense of self-worth, and justifiably so,” he continues. “We’ve jumped through so many hoops and run so many gauntlets in terms of our education and years of practice, we rightly feel that the service we provide has value and people should be willing to pay for it. But that doesn’t necessarily translate into others actually being willing to pay for them. Unless you’re strictly focused on cosmetic or refractive surgery and you already have a robust practice, you can’t count on your wealthy Medicare or PPO patients to convert to private cash pay just because they have the means. Especially if they can get those services paid for through their insurance.”

Keeping Things in Perspective

Of course, making changes of this magnitude to your practice is a scary prospect. Dr. Richardson observes that while few ophthalmologists in the United States seem to have actually created two-tiered practices or opted out of Medicare, many doctors talk about the possibility. “I think at this point, most doctors are looking at these options as hypothetical,” he says. “That will probably change over the next few years, but for now I think it’s a case of ‘Wouldn’t it be nice ….’ ”

In any case, when deciding how to proceed, Dr. Thompson says it’s important not to lose sight of the goal of treating your patients the way you yourself would want to be treated, regardless of the population you serve. “The difficulty,” notes Dr. Devgan, “is having the time and resources to live up to that ideal. We can’t provide that level of service for free for every patient, or even do it for pennies. And the pending Medicare fee cuts make the situation worse.”

Nevertheless, Dr. Thompson says he likes being able to treat all patients, and he does his best to treat them equally well, regardless of their financial status. ”I tell my team, this isn’t about eye surgery, it’s about people and making them feel valued,” he says. “When patients come in, we should treat them as if they’re coming into our home. Our practice has been very successful because of that philosophy. When you treat people well, you win in the long run.”