In our daily refractive surgery practice, we often encounter patients who are unhappy after refractive surgery, despite having undergone uneventful procedures and achieved a best corrected visual acuity of 20/20. This has led us on a quest to identify a common cause of these patients’ dissatisfaction. We found ourselves exploring the link between patients’ responses to refractive surgery and their personalities, as has been done in other research.1 The research question we posed was this: Is there a relationship between a patient’s personality and his or her postop treatment outcomes in the post-COVID era?

In this report, we’ll discuss the findings of our research, which has improved the way we preoperatively and postoperatively manage patients with different personality types. We hope you’ll gain insights that will help you incorporate similar refinements in your practice.

Step One: Initial Screening

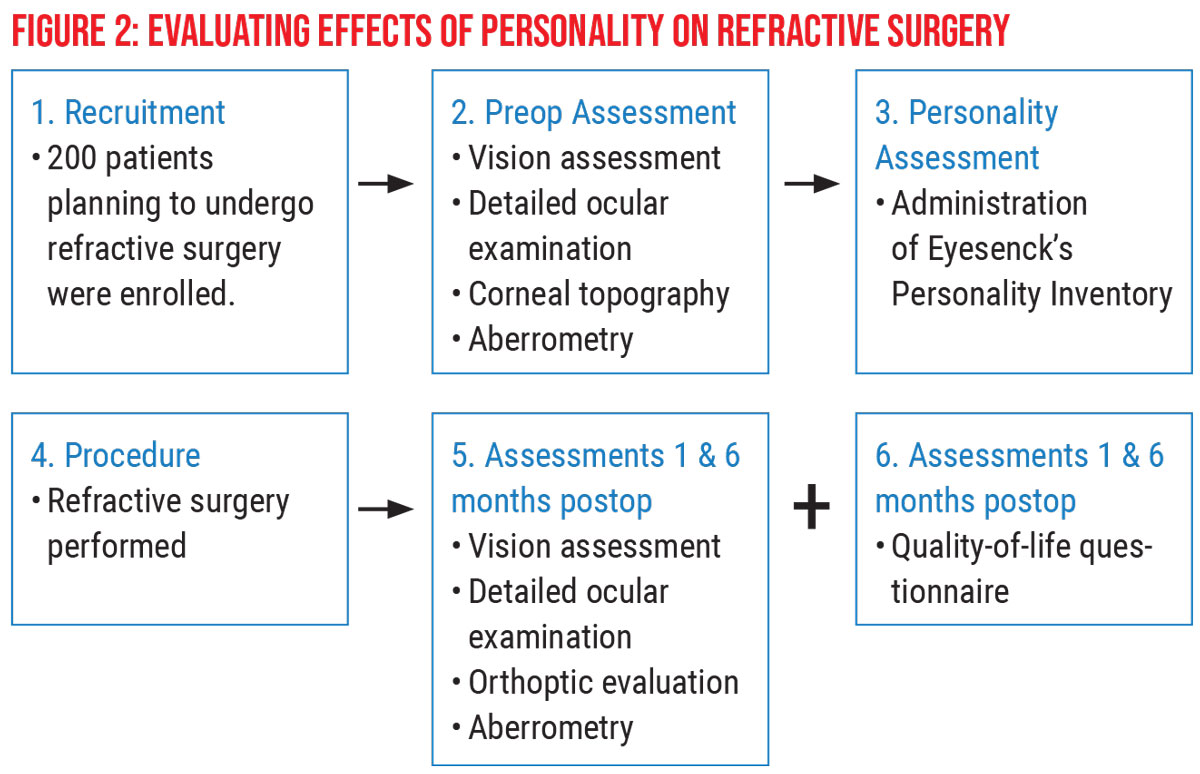

Our institution, the Narayana Nethralaya Hospital in Bangalore, India, performs 500 refractive surgery procedures each month. We have two operating surgeons and 30 other staff members. Patients come to us from all over India and other parts of the world. This study, conducted between 2018 and 2019, involved 200 patients. Here’s how we set it up:

|

| Click image to enlarge. |

After performing a vision assessment, detailed ocular examination, corneal topography and aberrometry, we asked each preop patient in the study to complete an Eysenck Personality Inventory. The EPI is a validated 57-item (yes/no format) questionnaire designed to measure two pervasive, independent dimensions of personality—extroversion/introversion and neuroticism/stability—that account for most of the variance among people’s personalities.2 We asked patients to fill out a hard copy of the questionnaire on the day they came in for their surgeries; it took seven to eight minutes to complete. The EPI, available at simplypsychology.org/eysenck-inventory.pdf), can be directly administered online at iluguru.ee/test/eysencks-personality-inventory-epi-extroversionintroversion or it can be printed out for patients to complete with a pen or pencil.

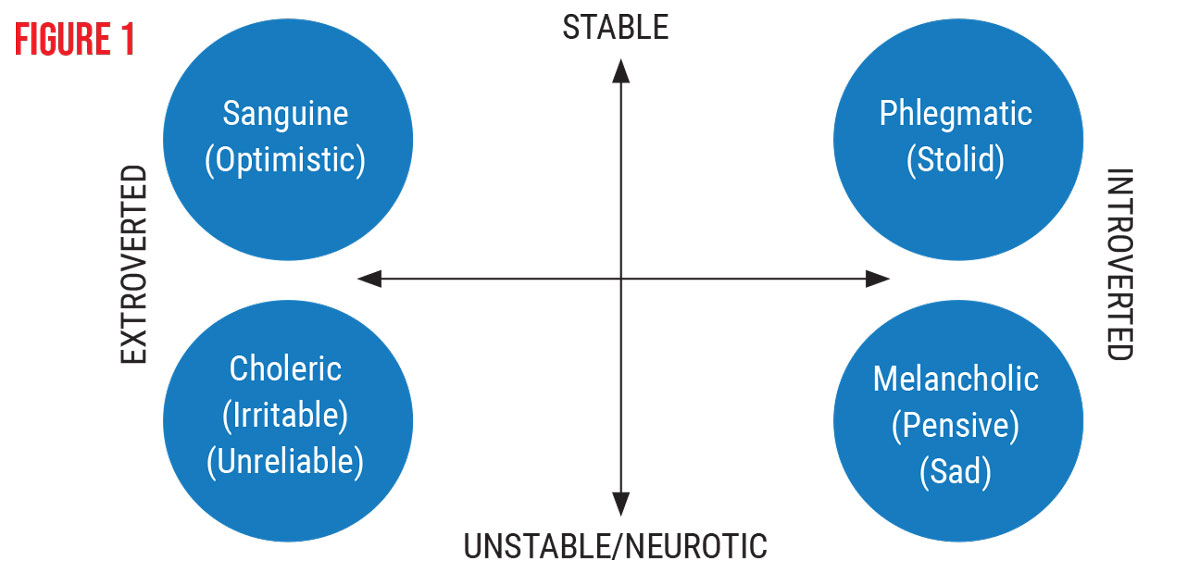

Based on the EPI scores we gathered, we categorized patients along two axes—ranging from extroverted to introverted on one axis and from stable to unstable/neurotic on the other axis. Additionally, as presented in Figure 1, below, we placed patients in one of the following subgroups:

- sanguine (optimistic), 57 patients, ranging from stable to extroverted;

- phlegmatic (stolid), 86 patients, ranging from stable to introverted;

- melancholic (pensive, sad), 44 patients; ranging from unstable/neurotic to extroverted; and

- choleric (irritable, unreliable), 13 patients, ranging from unstable/neurotic to extroverted.

|

The EPI also produced a so-called “falsification score” that proved valuable in evaluating the surgical readiness of patients. A score of 5 to 9 in the questionnaire results revealed patients who were likely not completely honest because they were trying to present themselves in a way that they believed would make a positive impression on the surgeons and clinical team. This falsification characteristic was identified both in patients who weren’t fully aware of their deceptive communication and in those with psychological issues who were best described as mendacious (consciously falsifying information).

Step 2: Postop Evaluation

All 200 patients underwent uneventful refractive surgery, including LASIK (120 procedures), SMILE (60 procedures) and flapless, transepithelial-PRK (40 procedures). We assessed all patients at one month and six months postop and determined that their clinical findings were virtually the same during both visits. (See Figure 2 for an overview of patient recruitment, preop assessment and personality assessment.)

Postop evaluation included vision assessments, detailed ocular exams, orthoptic assessments and aberrometry. All of the patients emerged from surgery with 20/20 Snellen vision. None had evidence of dry eye or orthoptic abnormalities, and all of the postop patients were advised to seek annual follow-up visits.

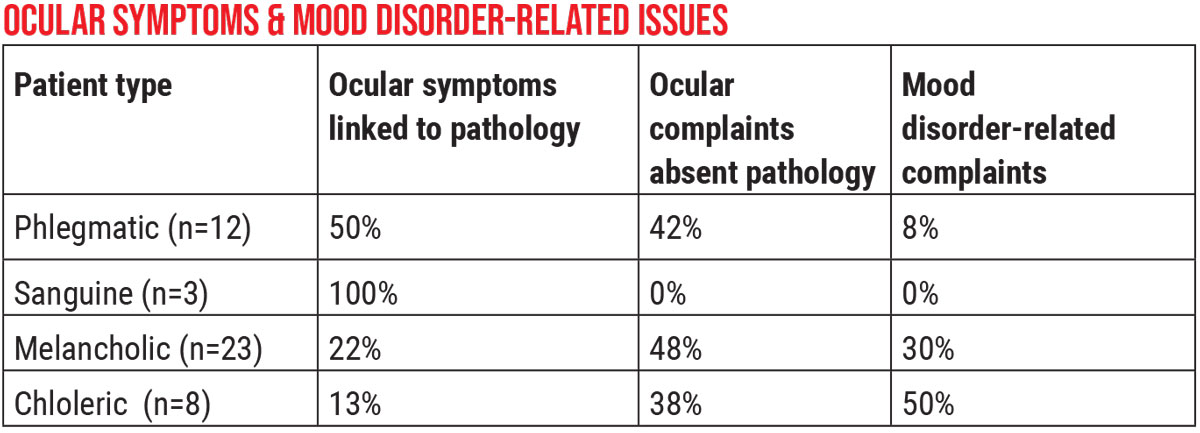

|

| Click image to enlarge. |

During both the one-month and six-month follow-up visits, the patients were also asked to take five minutes to complete a 20-item, Quality of Life Impact of Refractive Correction questionnaire, designed to measure the quality of life of presbyopes who require optical correction by spectacles, contact lenses or refractive surgery. The QIRC questionnaire, which has broad applicability for cross-sectional and outcomes research, was developed using Rasch analysis and has been shown to be valid and reliable.3

The resulting QIRC scores, determined to be statistically significant (p<0.000001), were correlated by our team with the patients’ personalities to try to determine if their personalities had any effect on their QIRC scores. Discernible patterns did arise. The mean QIRC scores were as follows, with higher scores reflecting a more positive outcome:

- phlegmatic patients: 54.11 (ranging from 53.66 to 54.70);

- sanguine patients: 52.60 (ranging from 51.5 to 53.60);

- melancholic patients: 44.57 (ranging from 43.89 to 46.44); and

- choleric patients: 39.20 (ranging from 35.70 to 41.10)

We found no variation in QIRC results based on surgical modality (trans-PRK, LASIK and SMILE). The most compelling finding was that the choleric patients experienced a significantly poorer quality of life related to vision compared to the three other patient types after surgery. We also evaluated an association of mood disorder complaints and ocular symptoms in patients who presented with and without accompanying ocular pathologies. We found that:

- choleric patients reported significantly higher mood disorder complaints than melancholic, phlegmatic and sanguine patients;

- melancholic patients predominantly included those reporting ocular symptoms that weren’t associated with pathology or high mood disorders; and

- phlegmatic and sanguine patients had limited ocular symptoms that were associated with some pathology.

The pattern—rather than the number—of reports was notable. “See Ocular Symptoms & Mood Disorder-Related Issues” above.

Step 4: A New Workflow

As a result of our findings, we created a new workflow, which we’ve followed since late 2019. Our goal is to increase patients’ satisfaction after refractive surgery. Below is the approach we now take at our hospital:

- Patients come in to undergo a preop evaluation for refractive surgery.

- Hospital staff members raise a “red flag” if refractive surgery candidates exhibit unusual behaviors, body language or interactions with other people. For example, the way they speak, the continuity in their thoughts, their maintenance of eye contact, their way of dressing, their interpersonal relationships and their history of recent emotional adversity may be worth noting.

- All preop patients, including those who prompt our staff to raise “red flags,” are required to complete the EPI.

- All patients are referred with their EPI results to their primary care doctor for guidance on surgical fitness and related issues. The phlegmatic and the sanguine personality types are advised to proceed with refractive surgery. Melancholics are managed with precautions, including the administration of counseling for the patient and his or her relatives.

- The patients who are identified as choleric are recognized as potentially having mental illness. They’re required to undergo psychological assessments and thorough counseling for three months before they’re considered for refractive surgery. At the time of surgery, the patients’ families or significant others are kept informed about their condition and are thoroughly educated on the prognosis of the surgery.

- The melancholics may be flagged because of abnormal behavior or communication, such as being

introverted or depressed. Close observation may associate them with difficult behavior or negative comments and thoughts. They don’t necessarily have to be referred for psychological treatment. Instead, we counsel these patients and their relatives and, if we identify potential psychological issues, we postpone the surgery for three months. Patients, relatives and possibly the patients’ friends are asked to sign a consent form that confirms among all parties their shared understanding of the prognosis of patients after refractive surgery. - Patients who have registered a falsification score of five or more are excluded from surgery and referred to a psychologist.

Step 5: Applying Pandemic-Learned Principles

How might our research and the implementation of our new workflow relate to COVID-19? Consider this: During the COVID-19 lockdown, many individuals across the globe experienced tremendous degrees of stress of one form or another, such as loss of employment, risks to the safety of themselves and their families, fear of infection by the virus, financial instability, isolation, working alone and remotely and loss or shutdown of their businesses. These factors all have the potential to negatively affect mental health, which has already been shown to have been influenced by the pandemic.4-7

We’re only beginning to document and understand the effects of the pandemic on mental health, including how pervasive these mental health effects may be and how long they may persist. Based on our experiences with some of the patients in our research, we believe the pandemic will likely play a role in our patients’ responses to refractive surgery for the indefinite future, suggesting a need for all refractive surgeons to be aware of the potential for a pandemic-related impact on their practices.Affected patients may present to us with certain unusual, non-optical complaints which we’ve documented, despite ocular examination findings within normal limits.

It’s because of our experience and our reflection on the current environment that we have incorporated the EPI questionnaire into the routine care we provide all of our patients, not just the ones whose behavior raises red flags.

Consistent with the effects of stress and anxiety associated with the pandemic, we’ve documented a greater proportion of melancholic and choleric patients who have presented with nonspecific body and eye pain, inability to concentrate and complaints related to mood disorder. Patients who have blamed these symptoms on the effects of refractive surgery have been found to be susceptible to the stress, anxiety and mood disorders that have been exacerbated by the pandemic. Both phlegmatic and sanguine patients have reported these symptoms, but the phlegmatic patients report them in a higher concentration. Ocular symptoms not related to any pathology have required appropriate management and counseling.

Many mental health centers have reached out to people with these issues. As clinicians, we feel a responsibility to do the same. The result of our efforts will be the provision of more support for patients in need, but also a protocol that’ll ensure a higher percentage of our refractive surgery patients walk away from our operating room stress-free and happy.

Dr. Shetty is a clinical and translational scientist at Narayana Nethralaya, Bangalore, India, and a member of the faculty in the department of ophthalmology, University of Maastricht, Maastricht, Netherlands. Dr. Khamar is a clinical and translational scientist and cataract and refractive surgeon at Narayana Nethralaya. She’s also a member of the faculty in the department of ophthalmology, University of Maastricht. Dr. Sengupta, serves in cataract and refractive services, optics and clinical research at Narayana Nethralaya. Drs. Shetty, Khamar and Sengupta report no relationships with companies that make products mentioned in this article.

1. Kerry K, Giedd JK, Mark J, et al. Personality in keratoconus in a sample of patients derived from the internet. Cornea 2005;24:3:301-7.

2. Nada Pop-Jordanova N, Ristova J, Loleska S. The Eysenck Personality Profile in selected groups of ophthalmological patients. Pril 2019:40:2:41-49.

3. Pesudovs K, Garamendi E, Elliott DB. The Quality-of-Life Impact of Refractive Correction (QIRC) Questionnaire: Development and validation. Optom Vis Sci 2004;81:10:769-77.

4. Heitzman J. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health. Psychiatr Pol 2020:54:2:187-198.

5. Fiorillo A, Gorwood P, The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and implications for clinical practice. Eur Psychiatry 2020;63:1:e32.

6. Hossain MM, Samia Tasnim S, Abida Sultana A, et al. Epidemiology of mental health problems in COVID-19: A review. SF1000Res 2020;9:636.

7. Czeisler ME, Lane RI, Wiley JF, et al. Follow-up survey of US adult reports of mental health, substance use and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic, September 2020. JAMA netw Open 2021;4:2.