|

Clinical Presentation

The hallmark presenting symptom of posterior scleritis is moderate to severe pain. Patients will often describe a deep, dull, boring pain that, classically, wakes them from sleep. There may be associated pain with extraocular motility, proptosis or other orbital signs. The degree of effect on vision can be variable, from minimally affected to significant vision loss. Intraocular pressure may be elevated in up to half of patients with scleritis, which may be due to rotation of the ciliary body and iris root into the angle causing angle closure without pupillary block, blockage of the outflow track due to inflammation, elevated episcleral venous pressure, peripheral anterior synechiae or neovascularization.

Deep redness and tenderness to palpation due to anterior scleritis also may or may not be present in cases of posterior scleritis. On physical examination, it’s important to lift the eyelids and ask the patient to look in all directions of gaze, as subtle anterior scleritis may not be immediately evident. Patients with strictly posterior scleritis may not have ocular redness but will describe discomfort with motility and may show restriction of eye movement.

Slit lamp biomicroscopy may demonstrate corneal edema, shallowing of the anterior chamber with anterior bowing of the iris and mild to moderate anterior chamber cell.

Fundus examination may show swelling of the optic nerve, exudative retinal detachment or choroidal effusions.

Workup

All patients presenting with scleritis should be worked up for associated systemic disease. First and foremost, it’s imperative to rule out infection with tuberculin skin testing or serum interferon gamma release assays such as quantiFERON Gold, as well as RPR and FTA-Abs testing for syphilis. Rheumatoid factor and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies, ANA, ACE (if the patient is not on an ACE inhibitor), lysozyme, ANCA, HLA-B27, as well as a CBC and CMP and chest X-ray should be obtained.

Imaging in Posterior Scleritis

Various imaging methods can yield important information in suspected cases of posterior scleritis.

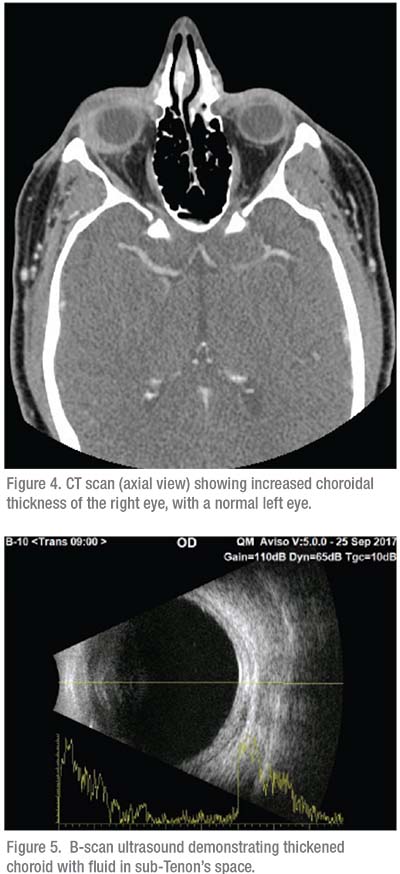

• B-scan ultrasonography. This can be crucial to the diagnosis of posterior scleritis, with the pathognomonic T-sign due to fluid collecting in the posterior episcleral space and extending around the optic nerve.

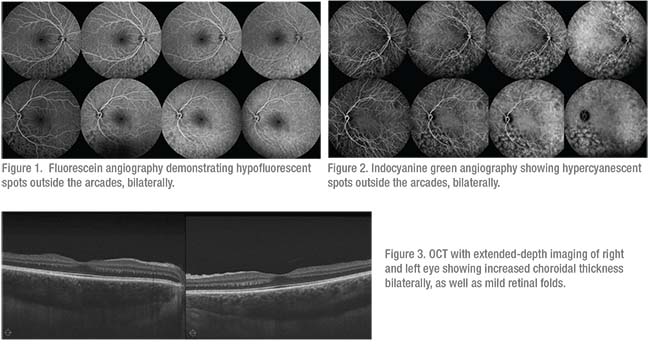

• Optical coherence tomography. OCT, particularly with enhanced depth imaging, can be quite helpful in the diagnosis of posterior scleritis, demonstrating increased thickness of the choroid. Often, subretinal fluid can be noted, even presenting in multiple foci.

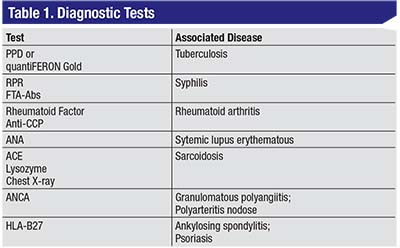

• Fluorescein and indocyanine green angiography. While posterior scleritis doesn’t have characteristic signs on FA, this modality can also be helpful in distinguishing posterior scleritis from other, similarly presenting issues, such as central serous retinopathy. Other characteristics often associated with posterior scleritis, such as optic nerve edema or serous retinal detachment, can also be demonstrated on FA. ICG can demonstrate fluorescent pinpoints in active inflammation.2

• Orbital CT scan. CT can help identify posterior inflammation, demonstrating increased choroidal thickness. In general, ultrasonography is considered superior to CT in imaging for posterior scleritis, but the latter can be helpful in ruling out idiopathic orbital inflammation and myositis.

Treatment

The treatment of posterior scleritis can be quite challenging. Topical NSAIDs and topical corticosteroids aren’t typically helpful, so systemic therapy is often initiated. Oral non-steroidals can be effective with various appropriate regimens, such as ibuprofen 600 to 800 mg q.i.d., piroxicam 20 mg daily and naprosyn 375 mg b.i.d., to name a few. In cases unresponsive to oral NSAIDs, high-dose systemic corticosteroids are often used, with typical doses of 1 mg/kg/day or approximately 60 mg of prednisone daily. These are tapered slowly over several weeks, with careful consideration of potential side effects such as weight gain, mood instability, blood-sugar abnormalities, etc.

|

If the patient continues to demonstrate active disease or is unable to tolerate corticosteroids, prompt corticosteroid-sparing immunosuppression is often warranted. Anti-metabolites such as methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil are employed, often to their maximal doses of 25 mg/week of methotrexate or 1,500 mg b.i.d. of mycophenolate. These medications may take up to six months for full effect and some patients

|

Prompt recognition and appropriate, often aggressive, treatment is key to recovery and preservation of vision.

Case Example 1

A 27-year-old Caucasian woman presented with bilaterally decreased vision and pain. Her visual acuity was 20/200 bilaterally, with a signficant myopic shift. Intraocular pressure was measured to be 55 mmHg in both eyes and slit lamp examination revealed shallow angles bilaterally with 360 degrees of iridocorneal touch. Fundus examination was notable for bilateral choroidal effusions. Fluorescein angiography (Figure 1) demonstrated hypofluorescent spots outside the arcades with no evidence of leakage. Indocyanine green (Figure 2) showed hypercyanescent spots in the same areas. Both eyes showed diffusely thickened choroid on OCT (Figure 3).

The patient was started on IOP-lowering drops and cycloplegics, as well as 60 mg of oral prednisone. One week later, IOP returned to normal, vision improved, and OCT showed clear improvement, in choroidal thickness. The patient’s systemic corticosteroids are currently being tapered.

Case Example 2

A 43-year-old Caucasian man presented to an outside ophthalmologist with a complaint of a red right eye. He was initially diagnosed with episcleritis and started on topical steroids. He then developed pain waking him from sleep, along with proptosis and restriction in eye movement. An orbital process was suspected and CT was ordered, demonstrating increased choroidal thickening of the right eye (Figure 4). He was referred to the uveitis service, where B-scan was performed (Figure 5) and he was diagnosed with anterior and posterior scleritis and started on oral prednisone. He was tapered over several weeks but flared, and thus required steroid-sparing systemic immunosuppression with methotrexate. The patient’s inflammation has resolved and he’s quiet and pain free. REVIEW

Dr. Rifkin is a uveitis specialist who practices at Ophthalmic Consultants of Boston. She’s also director of the Uveitis Service at New England Eye Center, and is an assistant professor of ophthalmology at Tufts School of Medicine. She can be reached at lana.rifkin@gmail.com.

1. Lavric A, Gonzalez-Lopez JJ, Majumber PD, et al. Posterior Scleritis: Analysis of Epidemiology, Clinical Factors, and Risk of Recurrence in a Cohort of 114 Patients. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2016;24:1: 6-15.

2. Auer, Herborn, Indocyanine green angiographic features in posterior scleritis. Am J Ophthlmol. 1998;126:3:471-6