Permanent keratoprosthesis (KPro) has restored vision in many patients with anterior segment diseases, however, it may lead to vision-threatening posterior segment complications. In this article, we’ll review the retinal complications that can occur with these devices and how to manage them.

Background

|

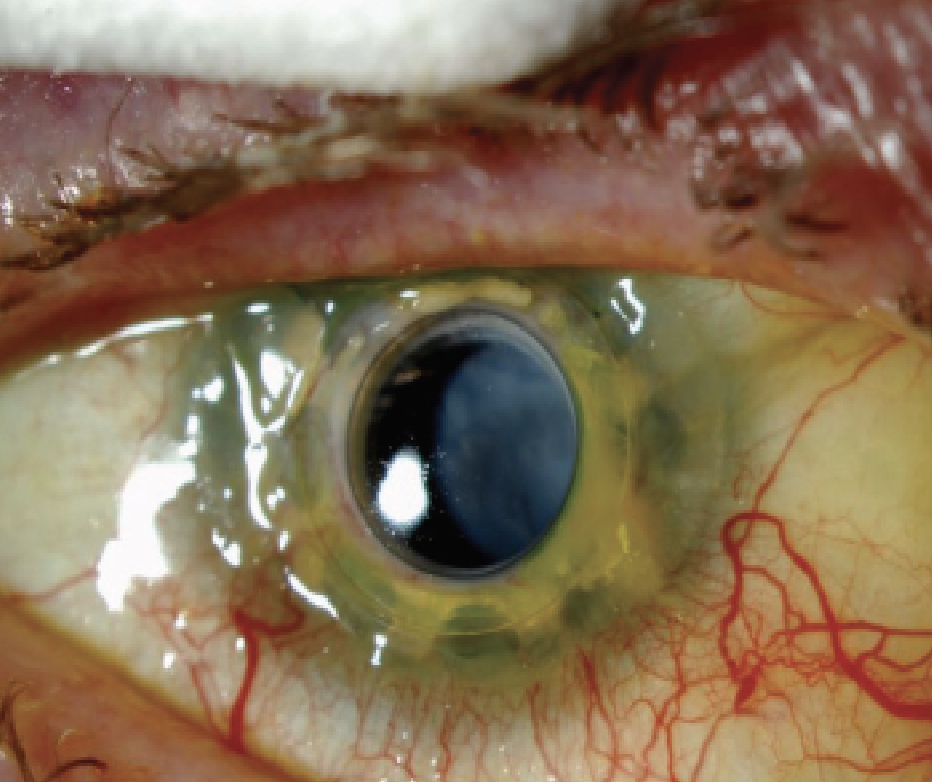

| Figure 1. A retroprosthetic membrane post-KPro that required surgical removal. |

KPro is an implantable device that serves to replace a native cornea with an artificial one, for patients with advanced corneal disease who aren’t candidates for traditional penetrating keratoplasty.1 The most common KPro in the United States is the Boston type I KPro, developed by Claes H. Dohlman, MD, and associates. The Boston KPro consists of a front plate with an optical stem, a back plate, a donut of donor cornea in between, which is sutured to the host cornea, and a titanium locking ring that holds the structure together.2 The design has undergone several adaptations, and now includes holes in the backplate, which enable the flow of nutrients from the aqueous humor.3

The type I design is by far the most frequently implanted model and is used for patients with non-autoimmune graft failure with good tear and lid function. The type II KPro is often used for patients with severe cicatricial corneal disease with deficient or absent tear function such as in Stevens Johnson Syndrome (SJS), Ocular Cicatricial Pemphigoid (OCP) or severe chemical burns. This device is similar, requires a permanent tarsorrhaphy, and has an extra 2-mm long anterior optical nub attached to the collar button that protrudes through the upper eyelid.4 Other permanent KPro devices include the AlphaCor (Addition Technology, Des Plaines, Ill.) and the Osteo-odonto keratoprosthesis or OOKP (originated by Italian ophthalmic surgeon Professor Benedetto Strampelli, modified by Rome’s Giancarlo Falcinelli, MD).

Although KPros are an effective treatment for many complex corneal diseases, vitreoretinal complications following the procedure represent a significant cause of vision loss and ultimately, KPro failure.5 Darin Goldman, MD, and colleagues showed that in eyes with posterior segment complications, 61 percent had 20/400 or worse visual acuity at most recent follow-up, while only 24 percent of eyes without complications ended up with such poor vision.5 With the increasing use and long-term stability of KPro, it’s important for ophthalmologists to be able to recognize and manage vitreoretinal complications to prevent unnecessary vision loss. Therefore, patients that undergo KPro implantation require long-term and close follow-up.

Indication for the Procedure

Indications for KPro include multiple graft failures or significant ocular surface disease caused by conditions such as SJS, OCP, autoimmune diseases, limbal stem cell deficiency, ocular burns, aniridia, herpetic keratitis, pediatric corneal opacities or silicone oil keratopathy.2,5 In addition, KPro has favorable vision outcomes and decreased risk of glaucoma complications when compared to repeat PK.6

Surgical Procedure

Following is a brief discussion of the steps of the KPro procedure, and how surgeons can avoid potential complications at each juncture:

• Patient selection. From a retina perspective, it’s crucial for patients to undergo a thorough eye exam, which often includes ultrasound to assess for the presence of vision limiting conditions such as retinal detachment, choroidal detachment or severe optic nerve disease. For the cornea surgeon, it’s important to evaluate the status of the ocular surface as well as lid abnormalities in order to determine the most appropriate procedure for the patient. If the visual prognosis and posterior segment status cannot be evaluated preoperatively, an exploratory vitrectomy with endoscopy can be performed to determine whether there is posterior segment potential to proceed with K-Pro implantation.2

• Advantage of pars plana vitrectomy and lens removal. At the time of KPro surgery, we often perform vitrectomy and lens removal at our institute, Weill Cornell Medical College (WCMC). If the eye to be implanted is phakic, the crystalline lens is removed and the optical power of the KPro is adjusted for implantation in an aphakic eye. If the eye is pseudophakic, we consider a similar approach and perform IOL removal at implantation in most cases, except for those with well-positioned IOLs and strictly corneal abnormality requiring KPro. The combination of vitrectomy and rendering most eyes aphakic at the time of implantation offers certain advantages to decrease the risk of future complications.

|

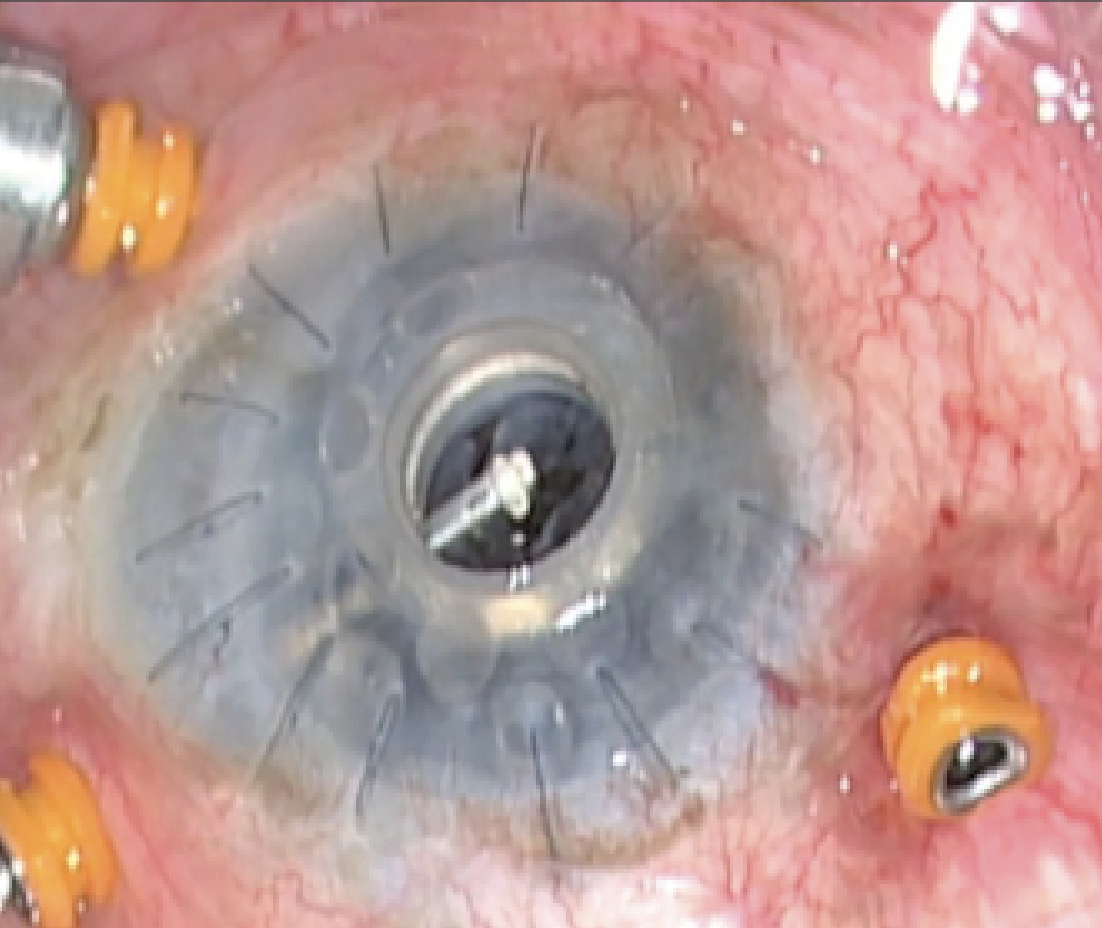

| Figure 2. When removing an RPM, avoid creating unnecessary retinal traction and possible subsequent retinal detachment. |

The advantage of lens removal is that it prevents future cataract formation (if phakic) or retro-IOL membranes, which wouldn’t only limit a patient’s vision, but the view to the retina as well, making it difficult to follow these patients in the future. It’s much more difficult to remove a RPM in a pseudophakic eye. Vitrectomy enables the surgeon to assess the visual potential of the eye (particularly the retinal and optic nerve status) and remove any inflammatory materials and debris; many pseudophakic eyes harbor substantial, and potentially inflammatory, residual lens material in the capsular periphery.1,7 Vitrectomy is typically performed with a 25- or 27- gauge system in a typical trans-conjunctival technique.2,8 We avoid doing maneuvers in the open eye as much as possible. For example, vitreous hemorrhage can occur during KPro placement and is often secondary to drop-down bleeding from the wound while the eye is open; effective treatment requires prompt eye closure and subsequent vitrectomy in a closed system.2 When indicated, a glaucoma drainage device is placed at the time of KPro surgery at WCMC. The reason is that it’s often difficult to accurately measure IOP in these patients, and many already have or will develop subsequent glaucoma.

Postoperative Management

Patients should be advised that KPro surgery requires frequent follow-up visits and life-long use of topical medications following surgery.1 Coordinated care with corneal surgeons, retinal specialists and glaucoma specialists is also crucial to manage these complex cases and potential future complications.7 Antibiotic prophylaxis regimens typically include topical vancomycin and a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone in the initial postoperative period, while dual-agent coverage should be continued for patients who are monocular or have autoimmune disease. Patients at lower risk of endophthalmitis are often treated with a topical fluoroquinolone or polymyxin B/trimethoprim for antibiotic prophylaxis. The placement of a bandage contact lens ensures ocular surface hydration, reduces the risk of stromal melt, dellen formation and necrosis; and improves patient comfort. However, care must be taken with close follow-up, as chronic bandage contact lens use can increase the risk of infections. Lastly, while topical steroids are recommended in patients with KPro to prevent inflammation, it’s important to closely monitor patients for side effects such as IOP elevation.9

Managing Vitreoretinal Complications

Though many KPro procedures proceed without issues, if a vitreoretinal complication occurs, the following guidelines and treatment approaches can help you treat them successfully.

|

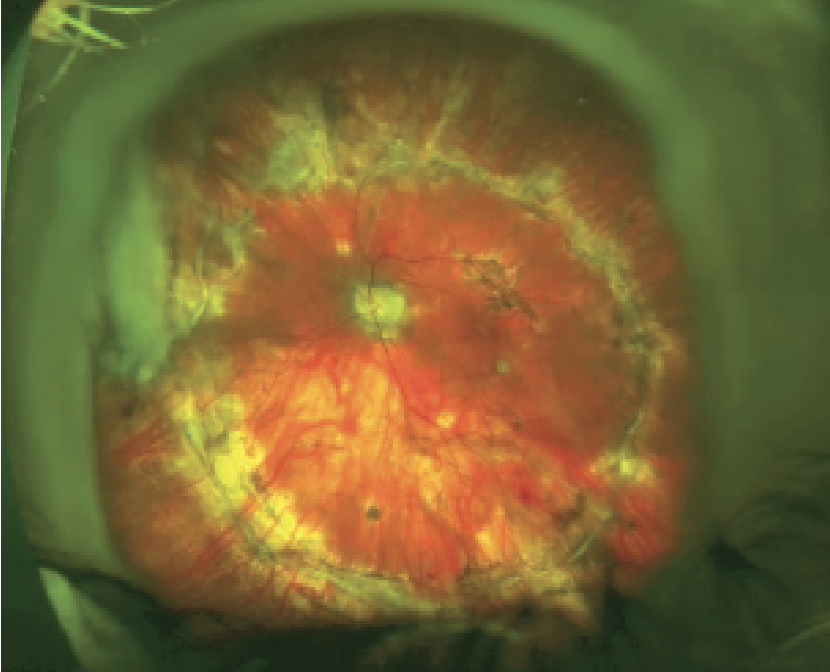

| Figure 3. This eye underwent KPro implantation followed by PPV for retinal detachment with PVR. |

Challenges to performing surgery in patients with KPro include achieving adequate surgical exposure, visualization and hemostasis. Attention should be made to avoid causing damage to the back plate, as iatrogenic manipulations can affect visual prognosis. Most importantly, maintenance of a firm eye and a closed system is critical.8 When a patient requires a pars plana vitrectomy after KPro implantation, sclerotomy placement should be made around 9 mm from the center of the KPro as the limbus is often not well defined.

• Retroprosthetic membrane (RPM). Retroprosthetic membrane is the most common complication after KPro surgery, affecting approximately one-third to half of patients.1,3,7,8,10,11 The membrane is thought to originate from the host’s corneal stroma, grow through gaps in Descemet’s membrane, migrate to the posterior surface of the KPro backplate and then can adhere to the anterior iris surface. An RPM can appear weeks to months after initial KPro surgery, and has been seen as early as a week postop and as late as four years after surgery.1

Risk factors for RPM include postoperative inflammation, retinal detachment, infectious keratitis and aniridia, and is potentially more severe in younger patients.1 They can become visually significant and limit both vision and your view of the retina, which can impede accurate follow-up. In addition, RPM can be associated with development of chronic hypotony (possibly secondary to traction on the ciliary body) can be a risk factor for future retinal detachment and sterile keratolysis.1,12 Figure 1 demonstrates a patient who required the surgical removal of an RPM following KPro placement. Figure 2 shows RPM removal. (See video of RPM removal below.)

Once an RPM becomes visually significant, initial treatment can include laser membranectomy with an Nd:YAG technique, although this can increase the risk of future retinal detachment.1,8 Thick RPMs are treated surgically. Pay careful attention to avoid creating unnecessary retinal traction and possible subsequent retinal detachment. During surgical repair, it’s important to minimize excess inflammation and hemorrhage, which can increase the risk of membrane recurrence.8 Despite surgical treatment, many RPMs can recur with rates of approximately 65 percent.1 In eyes that are left pseudophakic, it’s more difficult to remove a retro-K-Pro membrane, as there’s a risk of displacing the IOL or damaging the prosthesis; therefore, the IOL may need to be removed in order to clean the KPro.2,7 As previously discussed, we remove lenses and IOLs at the initial KPro surgery to decrease these issues.

• Retinal detachment. Retinal detachment is the second most common complication in patients with KPros, and can be potentially blinding. They can occur months to years following the initial KPro surgery. Retinal detachment has been reported in 2 to 17.6 percent of cases.3,5,8,10,11 Dr. Goldman’s study found that 16.9 percent of eyes (14 of 83) developed retinal detachment at a median time of 10.4 months after KPro implantation.5 Clemence Bonnet, MD, of the Corneal Biology Lab at UCLA, reported that among 224 Boston Type I keratoprosthesis surgeries performed, 28 (15.2 percent) developed retinal detachment at a mean of 10.9 months. Among these cases, they evaluated 21 retinal detachments surgeries, and identified vitreoretinal proliferation in 18 eyes (85.7 percent) and anatomic success following repair was achieved in 18 (85.7 percent) eyes.11 (See video below showing pars plana vitrectomy for retinal detachment with proliferative vitreoretinopathy.)

Retinal detachments can be either tractional or rhegmatogenous and can be caused by retinal breaks or proliferative vitreoretinopathy in the setting of chronic inflammation.1,8 These cases tend to be complex, many of which present with proliferative vitreoretinopathy due to the degree of intraocular inflammation. Patients may initially not be very symptomatic, as many already have limited vison secondary to other conditions such as advanced glaucoma or prior posterior segment disease. Therefore, patients should be followed routinely to detect detachment early. Given that the view of the peripheral retina in patients with KPro may be limited, B scan ultrasonography and ultra-widefield color fundus imaging is often recommended.11 At follow-up visits, all of our patients obtain a complete anterior and posterior segment exam, along with UWF imaging, and a B scan when indicated.

The surgical approach to repair retinal detachments in KPro cases is done via pars plana vitrectomy, with a low threshold for silicone-oil tamponade. Scleral buckling is often avoided due to the altered scleral and anterior segment anatomy in these patients. Advancements in surgical instrumentation, including smaller-gauge surgery, along with improvements in wide-angle viewing systems, allow for good peripheral visualization and safer PPV repair through the KPro. Silicone oil is often our tamponade agent of choice due to the need for a longer tamponade in these complex cases. In addition, some patients are monocular and require immediate postoperative functional vision.5 These patients should be co-managed with our glaucoma colleagues, as many have glaucoma filtering devices that need to be removed or ligated prior to oil placement. Perfluoro-n-octane may also be used as a temporary tamponade but should only be used for a short period of time due to its inflammatory qualities.7 For patients with KPros who require vitreoretinal surgery, the sclerotomy placement should be altered as described above, due to difficulty in locating a clear limbal landmark.

|

|

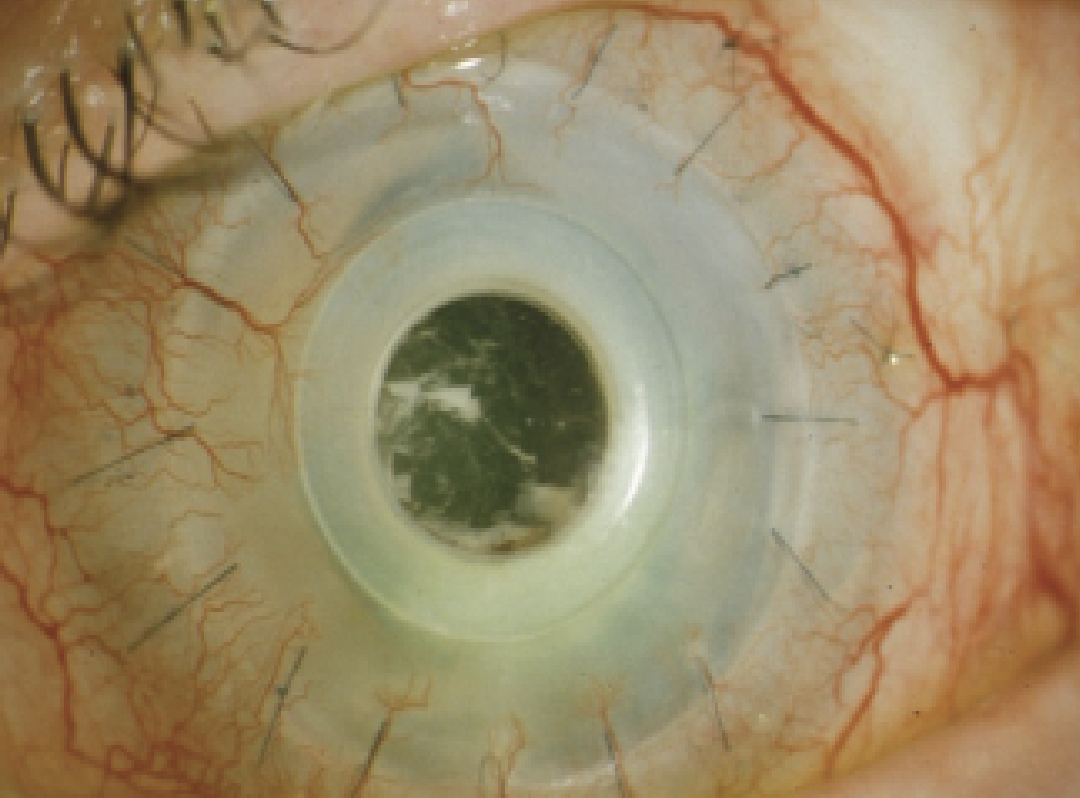

Figure 4. Infectious endophthalmitis from a coagulase-negative staphylococcus following KPro implantation. |

• Infectious endophthalmitis. Endophthalmitis is a potentially devastating complication, and can occur in 1 to 19 percent of KPro cases. Patients who’ve received KPros are at a higher risk of endophthalmitis, as there’s a conduit between the ocular surface and anterior chamber. Specific endophthalmitis risk factors include preoperative conditions such as autoimmune disease and poor dental hygiene.1 Since the advent of topical antibiotic prophylaxis, however, the incidence of endophthalmitis from gram-positive infections after KPro surgery has decreased from 12 to 5 percent.4 Bandage contact lenses can also lower the incidence of tissue melt, scleral thinning and breakdown of the KPro/host interface. Jay Chhablani, MD, of the University of Pittsburgh Eye Center, and his co-authors reported that among 136 eyes that received a Boston Type I KPro between 1999 and 2012, five cases (3.67 percent) of exogenous endophthalmitis occurred.13 In another study, University of California-Davis retina specialist Ala Moshiri and colleagues reported seven (19 percent) cases of endophthalmitis, all of which were salvaged with antibiotics and vitrectomy. Three of these cases developed retinal detachment.3

Endophthalmitis can present weeks to months and, rarely, years following KPro placement, once again highlighting the importance of close and long-term follow up. As discussed, prophylaxis with daily, broad-spectrum antimicrobial drops has significantly decreased the incidence of endophthalmitis. Historically, the most common organisms are gram-positive, although with vancomycin prophylaxis, fungal and gram-negative bacteria have become more common.1

Patients with bacterial infection present with sudden onset of eye pain, injection, decreased vision and intraocular inflammation, while fungal infections are typically more indolent and can start as keratitis in the KPro graft.4 Of course, endophthalmitis always requires immediate intervention. If you suspect it, perform an intravitreal tap or a vitreous biopsy to aid with diagnosis and help target antimicrobial therapy. Treatment involves the intravitreal injection of antimicrobials (i.e., vancomycin, amphotericin and ceftazidime) with or without surgery.1 A surgical vitrectomy has the advantage of removing enough specimen for analysis, can decrease organism load and remove vitreous scaffolding, which reduces the risk of subsequent vitreoretinal fibrosis and adhesions.8 Endophthalmitis following KPro placement has a poor visual prognosis.13

• Sterile vitritis/isolated vitreous opacity. Sterile vitritis is an immune-mediated, non-infectious process that can be triggered either by the KPro or by corneal antigens released during tissue necrosis that travel through holes in the KPro back plate into the posterior chamber. It can occur in zero to 14.5 percent of cases.1,5 Sterile vitritis presents as painless visual loss (without injection and tenderness), which can help differentiate it from infectious endophthalmitis. If it’s unclear whether the findings are infectious or not, we recommend a vitreous tap with antimicrobial injections.

Sterile vitritis can occur months to years after surgery. While the eye appears white and quiet, patients develop vitritis that may appear as a “snowflake” pattern. Sterile vitritis can be managed with peribulbar (triamcinolone or dexamethasone) or topical (prednisolone or difluprednate) steroid treatment depending on the severity. Patients typically can recover visual acuity after about two to 10 weeks of treatment.1

• Choroidal detachments/hypotony. Choroidal detachments occur in 1.7 to 16.9 percent of patients1,5 and can occur shortly after surgery or years after implantation. They’re often associated with inflammation and/or hypotony. Specifically, hypotony occurs in 1.8 to 11 percent of cases and is due to various causes, including corneal stromal necrosis with perforation, RPM or glaucoma device over-filtration. Small, stable choroidal detachments can be observed, while larger ones may require treatment. They can be managed with systemic or local steroids, while you address the cause of hypotony alongside your cornea and glaucoma colleagues. RPMs should be removed, particularly if they’re significant and potentially associated with the hypotony. Choroidal drainage can be considered in cases of appositional (“kissing”) choroidals to prevent subsequent vision loss and retinal detachment, though the underlying cause of hypotony should still be addressed.1,5

• Vitreous hemorrhage. Vitreous hemorrhage occurs postoperatively in 1.6 to 11 percent of eyes after KPro placement. VH can be secondary to intraocular bleeding from the trephinated cornea, lysis of iridocorneal adhesions or manipulation of other vascularized structures. Inflammation, intraoperative steroid use and diabetes are also associated with VH. B-scan ultrasonography should be performed when posterior segment view is inadequate, to rule out other pathology such as retinal or choroidal detachments. Though VH often resolves spontaneously, when it’s persistent it can be managed with vitrectomy.1 The Goldman study reported vitreous hemorrhage in 6 percent (5/83) after a median time of 0.3 months after K-Pro implantation. All cases were observed and ultimately resolved.5

|

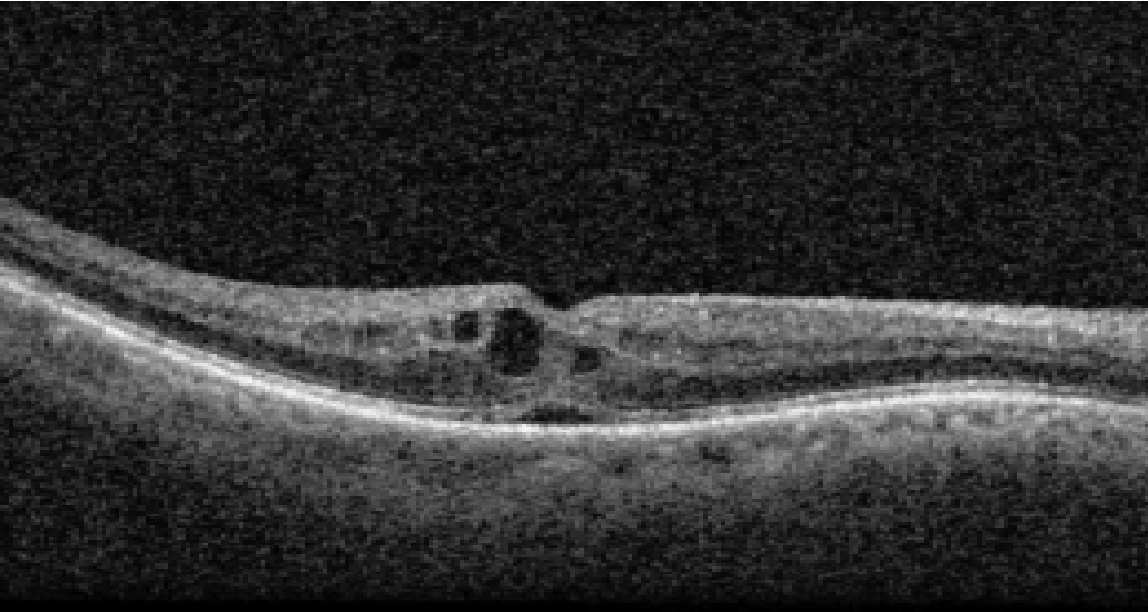

| Figure 5. An OCT of a patient who developed CME following KPro implantation. He was subsequently treated with topical difluprednate with resolution of CME. |

• Cystoid macular edema. Post-surgical CME is another common complication following KPro surgery. Goldman et al., reported CME in 10.8 percent of cases (nine of 83) at a median time of 4.1 months following surgery. Five of the eyes were treated with either intravitreal bevacizumab or triamcinolone, and two eyes required multiple injections.5 Optical coherence tomography is critical in diagnosing CME, while fluorescein angiography can be used in atypical cases to rule out other causes. CME can be managed with topical, periocular or intravitreal steroids; or intravitreal anti-VEGF medication, depending on the severity and response to treatment.

• Other complications. Other vitreoretinal complications that have been described include the development of epiretinal membrane or macular holes. Goldman et al., found ERM in 7.2 percent of eyes (six of 83) at a median time of 17.7 months after KPro placement,5 while Moshiri et al., reported four (11 percent) cases of ERM and one case (3 percent) of macular hole.3

Visually significant ERMs or macular holes benefit from pars plana vitrectomy and membrane peeling. Modern day small-gauge vitrectomy and wide-angle viewing systems greatly help with the surgery.

In conclusion, postoperative retinal complications following implantation of a permanent keratoprosthesis are a significant cause of vision loss. Therefore, it’s important for ophthalmologists to recognize these complications to make a prompt diagnosis and pursue the appropriate treatment. The most common retinal complications are retroprosthetic membrane, infectious endophthalmitis, sterile vitritis, retinal detachment and choroidal detachment. A retina specialist plays a crucial role in the preoperative evaluation, initial surgical implantation (when combined pars plana vitrectomy is performed) and in the postoperative care. Ultimately, close and long-term follow-up, along with coordinated care between cornea, retina and glaucoma specialists, are vital to managing vitreoretinal complications of KPros and preventing vision loss.

Dr. Nadelmann is a vitreoretinal surgery fellow at Weill Cornell Medical College.

Dr. D’Amico is professor and chair of the Department of Ophthalmology at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York-Presbyterian Hospital.

Dr. Orlin is a associate professor of ophthalmology at Weill Cornell

Medical College.

Dr. Regillo is the director of the Retina Service of Wills Eye Hospital, a professor of ophthalmology at Thomas Jefferson University School of Medicine and the principle investigator for numerous major international clinical trials.

Dr. Yonekawa is an assistant professor of ophthalmology at Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University. He serves on the Education Committee of the American Society of Retina Specialists and on the Executive Committee for the Vit Buckle Society, where he is also the vice president for academic programming.

1. Klufas MA, Yannuzzi NA, D’Amico DJ, Kiss S. Vitreoretinal aspects of permanent keratoprosthesis. Surv Ophthalmol 2015;60:3:216-228.

2. D’Amico DJ. The Gertrude D. Pyron 2016 Award Lecture of the American Society of Retina Specialists. Journal of VitreoRetinal Diseases 2017;1:3:159-168.

3. Moshiri A, Safi M, Morse LS, et al. Posterior segment complications and impact on long-term visual outcomes in eyes with a type 1 Boston Keratoprosthesis. Cornea 2019;38:9:1111-1116.

4. Behlau I, Martin KV, Martin JN, et al. Infectious endophthalmitis in Boston keratoprosthesis: Incidence and prevention. Acta Ophthalmol 2014;92:7:e546-e555.

5. Goldman DR, Hubschman JP, Aldave AJ, et al. Post-operative posterior segment complications in eyes treated with the Boston type I keratoprosthesis. Retina 2013;33:3:532-541.

6. Ahmad S, Mathews P, Lindsley K, et al. Boston type 1 keratoprosthesis versus repeat donor keratoplasty for corneal graft failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2016;123:1:165-77.

7. Kiang L, Sippel KC, Starr CE, et al. Vitreoretinal surgery in the setting of permanent keratoprosthesis. Arch Ophthalmol 2012;130:4:487-492.

8. Ray S, Khan BF, Dohlman CH, D’Amico DJ. Management of vitreoretinal complications in eyes with permanent keratoprosthesis. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120:5:559-566.

9. Boston keratoprosthesis (KPRO). EyeWiki. https://eyewiki.aao.org/Boston_Keratoprosthesis_(KPro). Accessed January 2, 2023.

10. Rishi P, Rishi E, Koundanya VV, et al. Vitreoretinal complications in eyes with Boston keratoprosthesis type I. Retina 2016;36:3:603-610.

11. Bonnet C, Chehaibou I, McCannel CA, et al. Retinal detachment in eyes with Boston type 1 keratoprosthesis: Surgical techniques and mid-term outcomes. Retina 2022;42:5:957-966.

12. Dokey A, Ramulu PY, Utine CA, et al. Chronic hypotony associated with the Boston type 1 keratoprosthesis. Amer J Ophthalmol 2012;154:2:266-271.

13. Chhablani J, Panchal B, Das T, et al. Endophthalmitis in Boston keratoprosthesis: Case series and review of literature [published correction appears in Int Ophthalmol 2015;35:1:149-54.] Int Ophthalmol 2015;35:5:673-678.