TRABECULECTOMY IS AN EXCELLENT PROCEDURE—when it succeeds. To ensure it does, you've got to avoid many landmines along the way, such as conjunctival buttonholes, over- and underfiltration, and hemorrhage. Over the years, we've seen what surgeons do well, and could do better, when performing this procedure. We've distilled our observations for you here.

Case Selection

The best way to solve a problem is to avoid it in the first place. Proper patient selection goes a long way toward achieving this.

As an object lesson, we just saw a patient the other day who needed intraocular pressure reduction, but was aphakic and on Coumadin. He wasn't a good trabeculectomy candidate, because of the scarred conjunctiva from previous surgery. Also, the fact that he was aphakic was even worse, as it's a strong risk factor for a suprachoroidal hemorrhage. Just because a patient has never had a trabeculectomy before doesn't mean you have to do one on him.

If you're considering performing a trabeculectomy on someone, when you examine him at the slit lamp, you have to ensure that the conjunctiva is appropriate. If he's had a previous surgery, the conjunctiva may be retracted back or be scarred and immobile. This will make your surgery more difficult.

One way to assess the conjunctiva is to have the patient look down at the slit lamp, and then take his lid and move it over the superior conjunctiva. If you note conjunctival movement, that's a good sign. However, if you see the so-called "concrete conjunctiva," that's a warning that you'll have to come up with a game plan to deal with it. This plan might be to avoid the trabeculectomy and insert a tube shunt. Or, if it's a patient who requires a trab because you wouldn't be able to get low enough pressures with a tube, then you will have to do a fornix-based trab instead of a limbal-based one.

Also, adjust your antimetabolite choice based on the patient. If you use high-dose mitomycin-C in an elderly Caucasian patient with virgin tissue, odds are you'll be dealing with a complication later. Therefore, mitomycin-C may not be the best choice in such patients; 5-fluorouracil might be a better one. Also, if you need to do a trab in someone with a concrete conjunctiva presentation, you'll want to use a larger dose of mitomycin.

And remember, a trabeculectomy in someone who won't follow your recommendations after the surgery, such as taking his medication and keeping up with the multiple postop visits, can be very risky. Something as basic as living a long way from your office and needing a driver in order to make postop visits can make someone a poor trabeculectomy candidate.

To help avoid problems later in the surgery and postoperatively, we recommend you initially make a paracentesis and fill the eye with Healon. This tip runs contrary to conventional wisdom of the past that advised us not to use Healon in trab patients. Now, however, we recommend you use it because it will stabilize your chamber, and you can always make an eye drain more later. This also helps avoid situations in which you're passing your initial corneal bridal suture and accidentally flatten the chamber.

Next, pass a corneal bridal suture to turn the eye down and avoid a superior rectus muscle hemorrhage from a rectus muscle bridal suture.

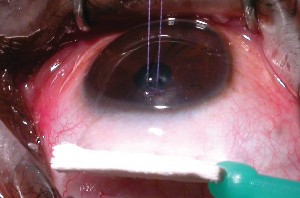

After the eye is stabilized with the suture, inject 2% lidocaine with epinephrine into the subconjunctival space as far back from the limbus as possible, and use a Weck Cel to squeegee it forward. The fluid will dissect the tissue planes that you want to separate, making your surgical dissection easier. The epinephrine helps decrease bleeding and, if you don't have perfect anesthesia, the lidocaine will make the patient more comfortable. You'll be amazed at how readily the planes will fall apart after you work the fluid forward with the Weck Cel. Occasionally, you can have your dissection up to the limbus in a limbal-based trab in a matter of three or four Weck Cel pushes in only five minutes. This maneuver also makes fornix-based trabs easier to dissect.

|

|

| After injecting 2% lidocaine with epinephrine far posteriorly, you can use a Weck Cel sponge to push the lidocaine forward. This causes separation of the tissue planes and makes the later creation of the conjunctival/Tenon's flap easier. |

After the fluid dissection is complete and you're ready to continue, here are the most troublesome intraoperative complications to be aware of:

• Buttonholes. The Weck Cel fluid dissection can help avoid complications by making the conjunctiva much more mobile and easier to handle, and this helps you avoid conjunctival buttonholes. If you've got a mobile conjunctiva that's not tacked down, and you can therefore see what you're doing, you'll be far less likely to cause a buttonhole with your scissors.

To help avoid a buttonhole, lift the conjunctiva with non-toothed forceps—we use Bishop Harmons—and put it on stretch. Some surgeons, however, may be hesitant to put the conjunctiva on stretch, for fear of tearing it. However, you're actually more likely to get a buttonhole if the conjunctiva is slack and redundant on itself, because you could inadvertently cut a fold and create a hole.

If you get a buttonhole, the number-one concern when you attempt to repair it is its location. If you're doing a limbus-based trab and the buttonhole occurs in the conjunctiva at the insertion of the limbus, then you can undermine a 10-0 nylon suture under the cornea and close the buttonhole with a mattress suture at the limbus. That is a not a common occurrence, however.

Usually, you'll get a buttonhole right in the middle of your operative area, where you want to perform your trabeculectomy flap. If this occurs, and you haven't applied an antimetabolite yet, try to shift your surgery away from the hole. For instance, if the buttonhole is at 1 o'clock, dissect further around to 11 or 10 o'clock so you can apply your antimetabolite there.

A two-layer closure is effective for buttonholes. First, close Tenon's with a 10-0 or 11-0 nylon suture, then do a purse string conjunctival closure on top of that.

A dollop of Healon around the buttonhole closure can be helpful for protection when you later apply the antimetabolite. The Healon appears to keep the antimetabolite away from the holed tissue that you want to heal, and helps you proceed with the trabeculectomy as planned, rather than having to abandon the antimetabolite.

Even if you aren't aware of any buttonholes, it's always a good idea to blow BSS underneath the conjunctiva before applying an antimetabolite, checking for telltale leaks through a buttonhole you may have missed. This avoids problems of accidentally applying mitomycin-C to the buttonhole, and allows you to move your surgery if you do happen to find a hole. If you use the antimetabolite and then find you've made a buttonhole, a vicryl suture (9-0 or 10-0 on a BV needle) can be helpful in closing the hole. Vicryl induces healing, and may help counteract the antimetabolite's effects on the buttonhole.

• Scleral tear/disinsertion. Similar to cases in which you find a buttonhole, moving your surgery can be helpful in eyes that have old scleral tunnels in one quadrant, or an old, badly healed extracap incision. In fact, if you see an old extracap incision preop, it might be better to opt for a tube implant in some cases, because the old incision will make it difficult for the flap to hinge properly, and it may disinsert at the old incision site.

Of course, there will be situations in which you need the low pressures that trabeculectomy offers. In such cases, try to find the part of the eye that's best healed, then make an extra-deep flap, trying to get as much tissue as possible. Be prepared with donor pericardium if it dehisces. You can use the pericardium to fashion a new flap. Donor pericardium is an excellent material to have in the OR. It can be stored in lyophilized form for a long while, and then rehydrated for usage.

Extra manipulation is a frequent cause of tears, so you have to make sure your flap is thick enough, and be gentle when handling it. Some surgeons, though, in an effort to be gentle, just scratch out the outline of a flap, rather than make a thick one. We recommend flaps that are half scleral thickness, erring on the side of making them thicker. Making them too thin will open you up to such problems as tearing with your forceps or tearing when they're sutured.

Also, don't be too vigorous with your bipolar cautery before you outline the scleral flap with your blade. If you burn the tissue with over-cauterization, the sclera will immediately retract when you cut it. If this occurs, instead of the edges of the flap meeting the edges of the opposing scleral walls, they will retract, leading to much difficulty getting scleral coverage and perhaps overdrainage.

To avoid over-cauterization, don't do too much, and don't have it on too high a power. Before you begin, set the cautery on a very low power and test the vessels away from where the flap will be to ensure things look good.

• Scleral block removal and iridectomy issues. In some cases, such as when the surgeon uses a retrobulbar block, the pupil may be somewhat dilated when you perform your iridectomy. This can result in an iridectomy that's too large, or in a full-sector iridectomy with visual issues and/or monocular diplopia.

So, if you are faced with a large pupil prior to making your punch, instill some Miochol. This will bring the pupil down and let you avoid creating an iridectomy that reaches down to the pupillary margin. The miosis also puts the iris on stretch, making it easier to grab, pull out and cut. Constricting the pupil also makes it less likely that you'll hit vitreous during the iridectomy.

We recommend a Kelly punch for creating the sclerotomy, because it's hard to push it down too deeply through both iris and zonules. If you use Vannas scissors to cut out the block, be careful not to insert the scissor tips too far. We've seen cases in which the surgeon used the sharp tip of the Vannas to cut the block underneath the scleral flap, but the scissors were inserted too far, disrupting the iris and zonules, with resultant vitreous loss.

• Vitreous prolapse. If you see vitreous in the wound, do a very thorough Weck Cel vitrectomy. Don't try to use a vitreous cutter in a phakic patient, because, more often than not, it will nick the lens. The Weck Cel vitrectomy involves using a dry Weck Cel to daub where the vitreous is presenting, then pulling a little bit of it out and cutting it with your scissors. The idea is to clear the sclerotomy hole as much as possible, then blow back everything else with Healon. The vitreous will then retract back into the vitreous cavity, and the Healon will firm the eye up for several days.

Also, after a vitreous prolapse, tie the flap down tighter at the close of surgery to keep the pressure elevated a little longer. Don't be as aggressive in trying to lower the pressure, because the last thing that an eye in which the vitreous has been violated needs is low pressure or hypotony; you don't want the patient to sneeze five days postop with a pressure of 3 mmHg and blow vitreous up through the sclerotomy.

It can be hard just waiting on a patient whose intraocular pressure is in the 20s because you have Healon in the chamber, but that's what you have to do. The antimetabolite will allow you the luxury of waiting it out.

• Bleeding. To avoid this complication, avoid cutting the iris base when you make your iridectomy. If bleeding does occur, though, a good response is to drip cold BSS, with or without phaco-strength epinephrine, on the vessel and wait for the bleeding to stop. The cool BSS helps promote vasoconstriction. This usually only takes a few minutes. You can also go after the bleeding vessel with monopolar 23-ga. cautery, taking care not to go through the zonules.

If a suprachoroidal hemorrhage occurs, this is a dire complication that shifts your focus from performing a good trabeculectomy to just trying to save the eye. If you can manage to close the sclerotomy quickly, using any means necessary, and prevent the hemorrhage from filling the eye with blood, you've done well. You can come back at a later date and address the glaucoma.

• Closing the scleral flap. Thanks to antimetabolites, you can tie down the scleral flap tightly with multiple sutures without fear of it scarring over. Our method usually involves two releasable sutures near the limbus, and two laserable sutures farther back that we can lyse in the postop course as needed to increase outflow and lower the pressure gradually. The idea of all these stitches is that you can always pull a suture and lower the pressure if you have to, but you can't increase it by tying the flap down postoperatively. Tying the flap down tightly at the close of surgery helps avoid postop hypotony, bleeding problems and choroidal effusions.

Unlike trabeculectomies done prior to antimetabolite use, in which a small ooze of aqueous was necessary to ensure success, antimetabolite trabs can be closed completely (with no ooze) and then opened up gradually in the immediate postop period.

Early Postop Complications

Vigilance and appropriate follow-up will allow you to detect and respond to complications that occur in both the early and late postop periods. Here are the complications to watch for:

• Flat chamber. If you see a flat chamber on postop day one, first make sure it's not a case of aqueous misdirection, which is more likely to occur in eyes that, at some point, overdrained—yet another reason to avoid significant hypotony.

If it's not aqueous misdirection, and the chamber is starting to shallow and the pressure is getting lower, it's important to act quickly, rather than waiting for it to become flat. It's much easier to stop the complication as it's occurring than to manage a patient with a grade-3 chamber in which the lens and cornea are touching.

The main causes of overdrainage are an insufficient number of sutures in the scleral flap, flap shrinkage due to overcauterization and/or a thin flap. A thin flap can result in the sutures causing cheesewire holes that allow too much fluid to drain out.

One method for treating overdrainage involves Healon V. If you partially fill the chamber with the viscoelastic, that can give the eye a chance to heal around the overdraining sclerotomy hole and "catch up" with the trabeculectomy's effects.

Another option is the contact lens technique. This involves placing an oversized contact lens (17 to 24 mm) on the cornea. This large lens will overlap onto the sclera, covering the bleb and compressing it, allowing the ciliary body time to recover from the insult of surgery and start producing aqueous. Meanwhile, the conjunctiva will be doing some healing. This technique also helps with 360-degree blebs.

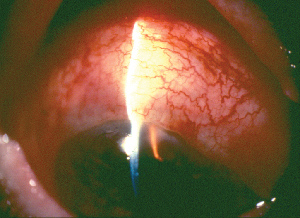

|

|

| An oversized contact lens on an overdraining bleb. Note the compression of the bleb tissue under the lens. |

• Choroidal effusions. If you don't have a buttonhole but are seeing signs of overdrainage with a shallow/flat anterior chamber or a very low IOP, check for choroidal effusions. A simple one-, two- or three-quadrant choroidal effusion will often resolve by itself, as long as you don't have lens-corneal touch in the anterior segment and the choroidal effusions aren't touching in the posterior segment. If they kiss in the back of the eye, however, there are concerns that this can cause adhesions to form that might give rise to retinal detachments later on. At that point, the choroidal effusions would need to be drained.

Again, as with many postop complications, choroidal effusions are most likely due to hypotony, so it helps to address the low pressure with either the contact lens method or by reforming the anterior chamber with Healon V. These approaches may enable you to establish a normal pressure and change the hemodynamics in the eye, forcing the effusions to resolve.

• Underdrainage. Be sure to watch the patient postoperatively for signs of excess healing, such as increased vascularization, a lower bleb or the IOP creeping upward. The third will happen last. If you see increased vascularization, then, even if the pressure is 10 mmHg, you've got to jump on it right away, because it's a sign that trouble is around the corner.

You can address excess healing with several methods, in this order:

• increased (up to hourly) topical steroids;

• 5-fluorouracil injections;

• subconjunctival or peribulbar Decadron injection;

• releasing sutures from the flap (fluid flowing through the conjunctiva can retard healing very well); and

• ocular massage.

The final treatment, ocular massage, is a helpful, though underutilized, way to help restore flow, and it's something patients can do themselves. As the list dictates, don't move on to massage until you've tried the other methods, however.

The proper massage technique involves the patient looking in a mirror, placing a finger on his lower lid, elevating the lid so it covers the lower part of the globe, and then gently pushing in with enough force so he's aware that he's pushing, but not so much as to cause discomfort. Have him do this for 10 seconds, take a 10-second break, then repeat it for another 10 seconds. We've found this approach tends to push fluid through the sclerotomy and break down adhesions in the subconjunctival space.

The caveat is that a patient can't perform ocular massage for the first week to 10 days if he's got a fornix-based bleb, in order to give the eye enough time to heal the connection between the cornea and conjunctiva. Doing it before this period is complete could pop fluid out of the bleb.

You'll also want to make sure that the underdrainage isn't the result of blockage in the internal structures. To do this, use a goniolens and examine your sclerotomy from the inside. The main things that may be causing the blockage are iris, vitreous or blood.

If you see a blood clot in the sclerotomy, observe it for a few days, and let whatever was bleeding settle down. Then, after about a week, carefully inject tissue plasminogen activator into the anterior chamber. If you use this injection too soon, you can induce more bleeding, so be sure to wait the week. This approach can also clear blocked sclerotomies years later, when the blockage occurs from fibrin that develops after another eye surgery.

Alternatively, if you see iris blocking the sclerotomy, sometimes an intraocular Miochol injection can help. But frequently, if either iris or vitreous is blocking the sclerotomy, a return to the OR is necessary to reopen the sclerotomy or do another procedure.

Late Postop Complications

Here are the main problems that can occur just when you think you're safely out of the woods:

• Late bleb leak. This has become more common with the use of antimetabolites. The threat of a late leak has made a lot of people shift to fornix-based trabs because they provide a more diffuse bleb. Surgeons will also apply the antimetabolite over a much broader area, not a very small one, in order to establish as broad a bleb as possible. This avoids having a tiny area of mitomycin-C treated bleb, which is more likely to be associated with a late leak or even blebitis.

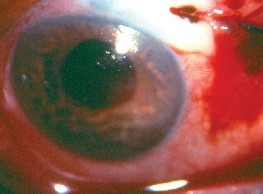

|

|

| Intra- and peribleb autologous blood injection can help counteract bleb leak or overdrainage and hypotony. |

When there are multiple ways to treat something, that usually means no single one is best. You have to try different approaches to repairing the leak, because patients respond differently. Unfortunately, in many cases you have to take the patient back to the OR and do a surgical revision of the bleb, pulling down fresh tissue to cover the leak.

• Blebitis. This involves pus in the bleb and cells in the eye, and is a serious, potentially blinding situation. Therefore, any post-trab patient who presents with a red eye should be put on antibiotics immediately. Avoid placing him on any topical steroid until blebitis has been ruled out. We recommend using one of the fourth-generation fluoroquinolones, which have very nice strep and staph coverage, which you need for a bleb. They also cover H. influenzae well.

Be sure to tell your patients that if they get a red eye to come see you, and to stay away from emergency rooms or clinics. We've had a couple of cases in which trab patients went to ERs for their red eyes and were prescribed a combination of antibiotic and steroid—a typical, broad-spectrum response. However, in these patients, the steroid can let the infection get out of hand. If you don't jump on it quickly, and instead let the bacteria get a couple of days' head-start in the eye, you may be facing full-fledged endophthalmitis and profound vision loss. Of course, if the patient develops blebitis, even if there's no anterior-chamber involvement yet, initiate fortified antibiotics.

If you notice that the cells are moving from the anterior chamber to the vitreous cavity, it's time to get a retinal specialist involved, and to begin intravitreal antibiotics. You can save the eye if you catch the infection quickly.

• Tenon's cyst. This is an over-exuberant healing response of Tenon's. The bleb will appear elevated and taut, and the IOP will begin to creep up into the 20s and 30s. This complication is less frequent with the use of antimetabolites.

The cyst will sometimes resolve by itself, though with suboptimal pressure. During the observation period, a 5-FU injection can be helpful. Other times, however, you have to go in with a bent 27-ga. needle and try to break up the fibrosis at the slit lamp.

Sometimes, as you're about to begin a trabeculectomy, you don't even want to think about complications and the headaches they can cause. However, this may be the best time to think about them. A little forethought and preparation can ensure a smoother procedure and better results in the long run.

Drs. Smith and Doyle are associate professors of ophthalmology at the University of Florida College of Medicine.