Diagnosing and monitoring glaucoma isn’t always straightforward, and that’s especially true when retinal pathology is present. When glaucoma and retinal disease coexist, it can be difficult to determine whether glaucoma has progressed—or even if the patient actually has glaucoma. Similarly, a change in retinal status can alter test results, leading us to believe a glaucoma patient’s disease may have worsened when the change is actually due to a retinal condition.

In this article I’ll focus on how retinal issues can affect visual fields and optical coherence tomography data when evaluating glaucoma. Many retinal conditions can affect the results of these tests, including abnormalities of the vitreoretinal interface such as posterior vitreous detachment and epiretinal membranes; vascular abnormalities; macular diseases such as age-related macular degeneration; retinal detachments; and other conditions such as retinal dystrophies, chorioretinitis, sickle-cell retinopathy and retinopathy of prematurity. Furthermore, treatments used to address retinal disease such as panretinal photocoagulation, pars plana vitrectomy, membrane peeling and the use of silicone oil or hydroxychloroquine, can have iatrogenic effects on the results of the tests we use to evaluate glaucoma progression.

Here, I’ll provide an overview of how retinal conditions can impact a glaucoma clinical evaluation; then I’ll review several case examples of situations in which common (and less-common) retinal conditions affected test results with significant implications for clinical decision-making and management. Finally, I’ll share strategies for distinguishing between real glaucoma progression and issues related to retinal disease.

Don’t Assume It’s Glaucoma

The first and most important strategy when managing a patient who has (or may have) glaucoma is: Don’t assume a change in test results means that the patient’s glaucoma has progressed.

Sometimes, for example, you may find that there’s been a major change in one or more tests since the patient's previous visit. If there’s a sudden change in the test results, it's important to assess the validity of the test and look for possible retinal artifacts. After checking on the test’s reliability, I look through the patient’s history and perform a detailed dilated eye exam. Did the patient develop a new medical or retinal condition, or undergo a surgery or laser procedure in the intervening period? That might explain the sudden change.

For example, I’ve seen patients who had a dense arcuate defect when the visual field was previously normal. A clinician could certainly interpret that to mean that the patient has worsening glaucoma. However, a macular OCT may show that the defect can be explained by profound ischemic thinning of the retinal nerve fiber layer and other inner retinal layers—changes that happened as a consequence of a branch retinal artery occlusion that occurred during the intervening time period.

Retinal surgery can also lead to artifacts by altering the thickness of the RNFL. We know that a pars plana vitrectomy with membrane peel can release traction on the retina, causing a decline in RNFL thickness. Using silicone oil can also potentially have toxic effects on the RNFL. Finally, patients who have proliferative diabetic retinopathy can develop glaucoma, and it can be hard to monitor these patients because they can develop visual field defects and OCT abnormalities related either to the diabetic retinopathy itself or to treatments such as PRP.

PRP can be related to a number of testing artifacts. First, laser destruction of retinal tissue can cause visual field defects. Second, regressed neovascularization can appear as fibrous tissue on the optic nerve; this can create artifacts on an OCT scan by affecting RNFL thickness measurements.

Interestingly, reports on PRP’s impact on RNFL thickness have been inconsistent; some studies have found that the laser treatment increases RNFL thickness, while others have found that it decreases the thickness. Either way, it’s important to be aware that OCT measurement of the RNFL in a patient with diabetic retinopathy may be altered by the disease and its treatment. This contributes to the difficulty of looking for signs of glaucoma and/or glaucomatous progression in patients with a history of proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

The bottom line is that retinal problems can create significant changes in glaucoma test results, making it harder to determine the status of an individual’s glaucoma.

Real-world Case Histories

Here are some examples of patients in whom retinal changes affected the test results on which we’d normally base our glaucoma evaluation.

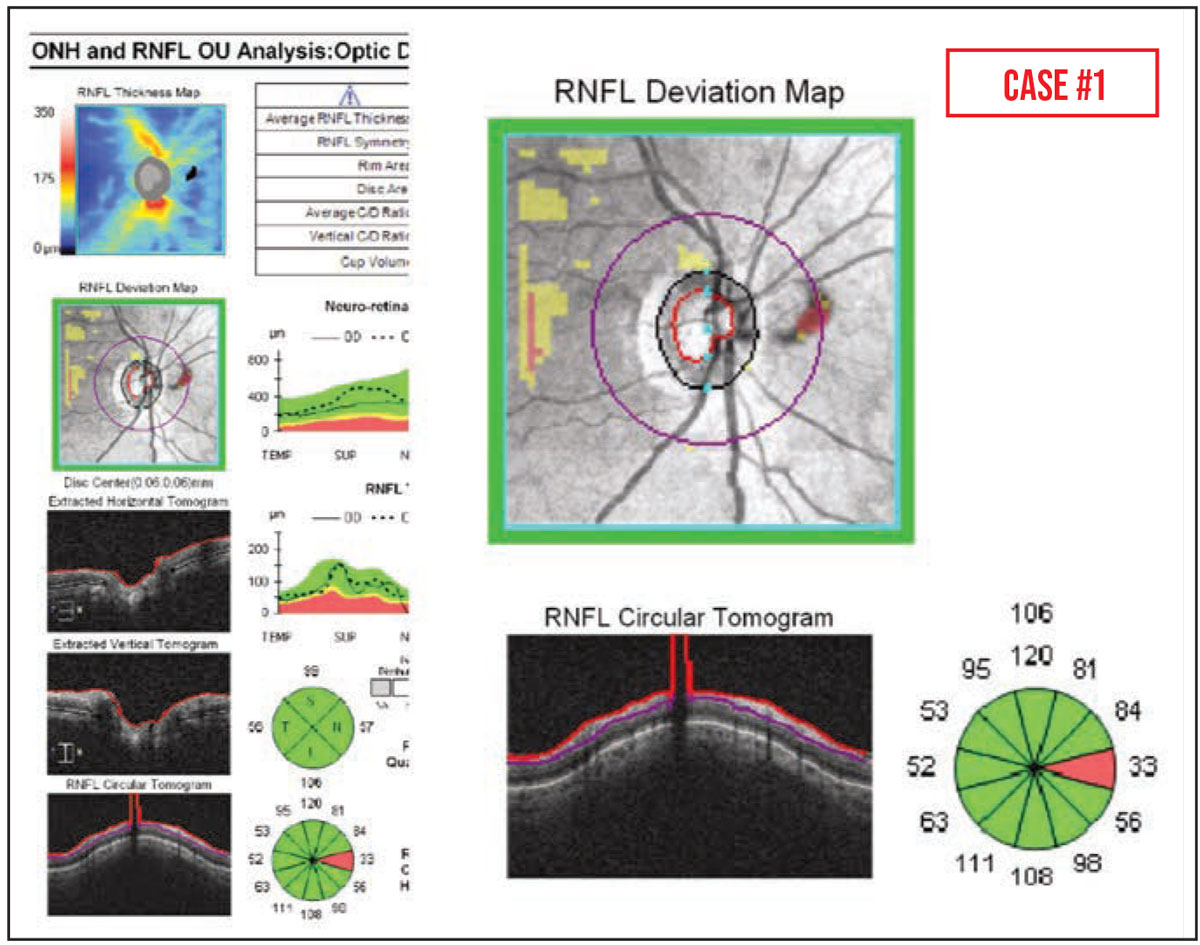

Case #1: This elderly patient with ocular hypertension appeared to have a new area of nasal RNFL thinning on OCT. However, this was an artifact caused by a PVD blocking the scan circle. (Partial PVDs can also lead to falsely thin RNFL measurements, due to erroneous segmentation.)

|

It’s worth noting that partial PVDs are common—they’re visible in up to 40 percent of peripapillary RNFL OCT scans—and traction caused by epiretinal membranes can also increase OCT RNFL thickness measurements over time.1,2 This can lead to the appearance of focal RNFL thinning, due to the release of the attachment to the posterior hyaloid face following vitrectomy with membrane peel.

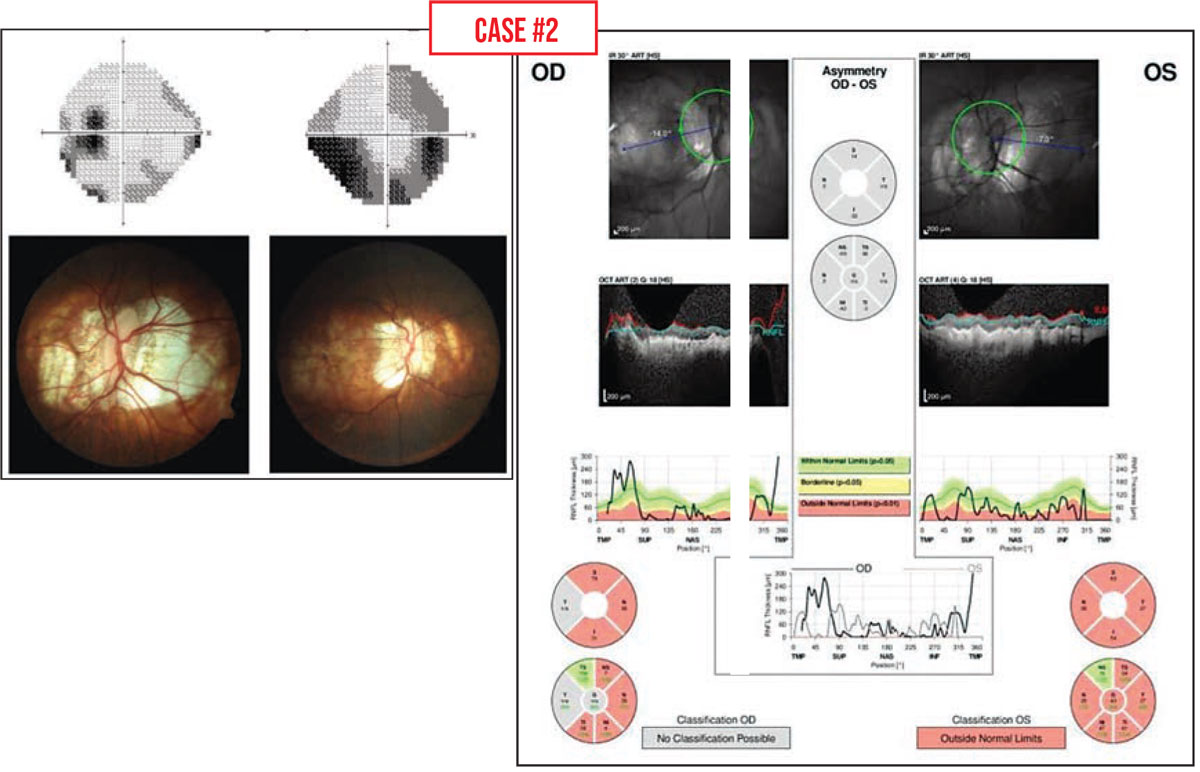

Case #2: This patient had myopic degeneration and large areas of peripapillary atrophy. Traditional testing for glaucoma in a high myope (-6 D or greater) tends to produce abnormal results; the visual field, optic nerve and OCT scans may all look abnormal. That can make it quite difficult to determine whether the abnormalities are the result of high myopia or glaucoma.

The best way to proceed in this situation is to perform all of the usual baseline glaucoma tests and then look for change over time, when possible, as you follow the patient. If you find progressive change, glaucoma rather than myopia is likely to be the cause of some of those abnormalities.

Images courtesy of Jullia Rosdahl, MD, PhD. |

It’s worth noting that in this situation, visual field testing may be more useful than OCT scans. The RNFL in these patients is often anomalous and already too thin to follow for changes. But if the visual field is deteriorating over time, that suggests that glaucoma is present and worsening.

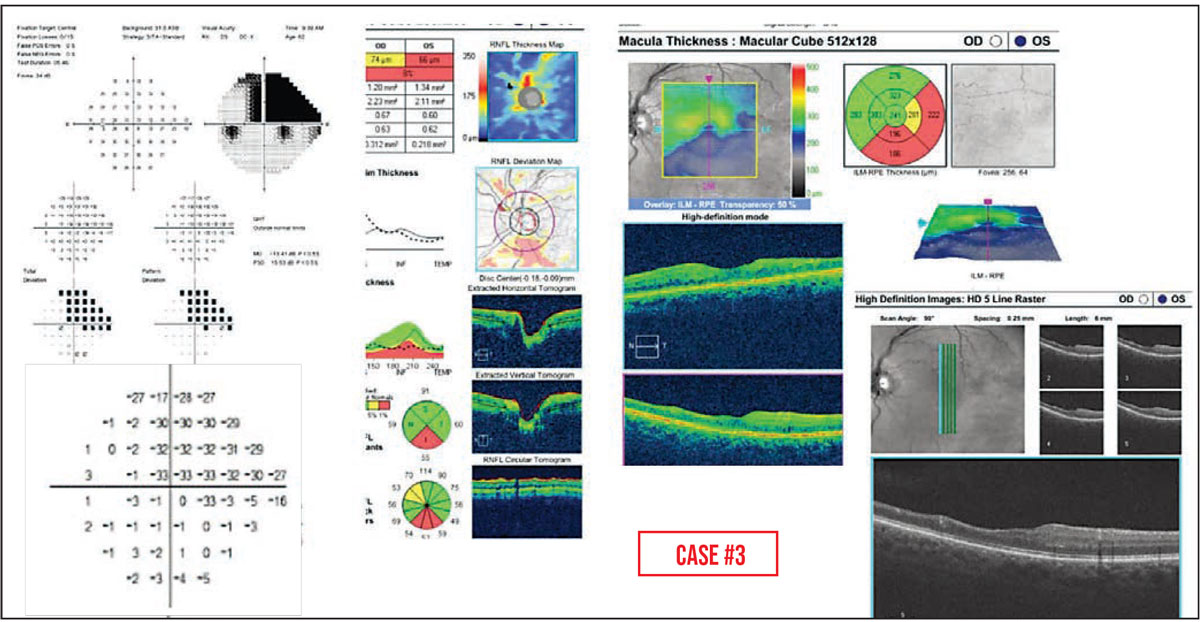

Case #3: Retinal diseases typically cause dense defects on visual field testing. Here we see an abrupt transition between -33 and -1dB on the OCT pattern deviation plot, corresponding to a region of marked inner retinal atrophy that was caused in this case by a branch retinal artery occlusion.

|

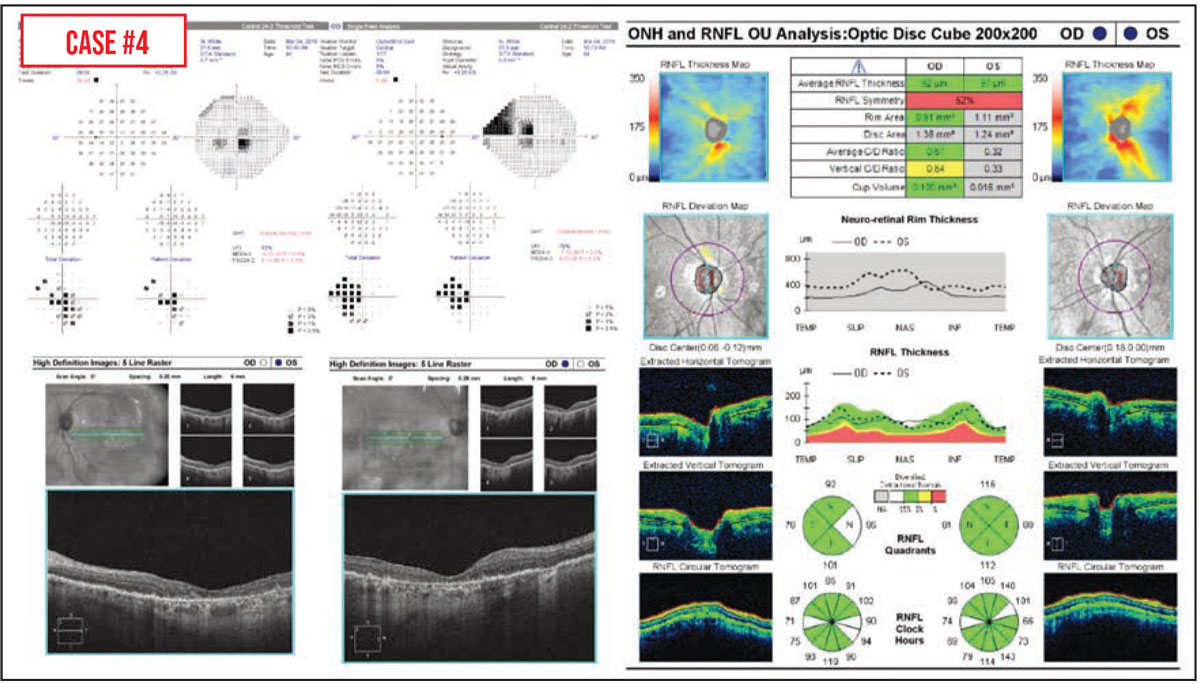

Case #4: Macular degeneration is another condition that can make it difficult to tell how much of a patient’s vision change was caused by glaucoma progression, in part because advanced age-related macular degeneration can cause central visual field defects.3 In this situation, peripapillary RNFL OCT—rather than either macular OCT or visual field testing—may be more helpful for assessing glaucoma progression. That was the case for this patient, who had geographic atrophy and abnormal visual field tests but healthy optic nerves. In addition, I’ll often check the macular OCTs of patients with a history of macular degeneration to look for any subretinal fluid or other problem that might be treatable.

|

If an older patient has both macular degeneration and glaucoma, it can be really challenging to parse out exactly how much vision loss is being caused by the progression of either condition. Sometimes, in cases where it’s not possible to distinguish the two, we lower the intraocular pressure in the hope of preventing further vision loss, in case it’s being caused by glaucoma.

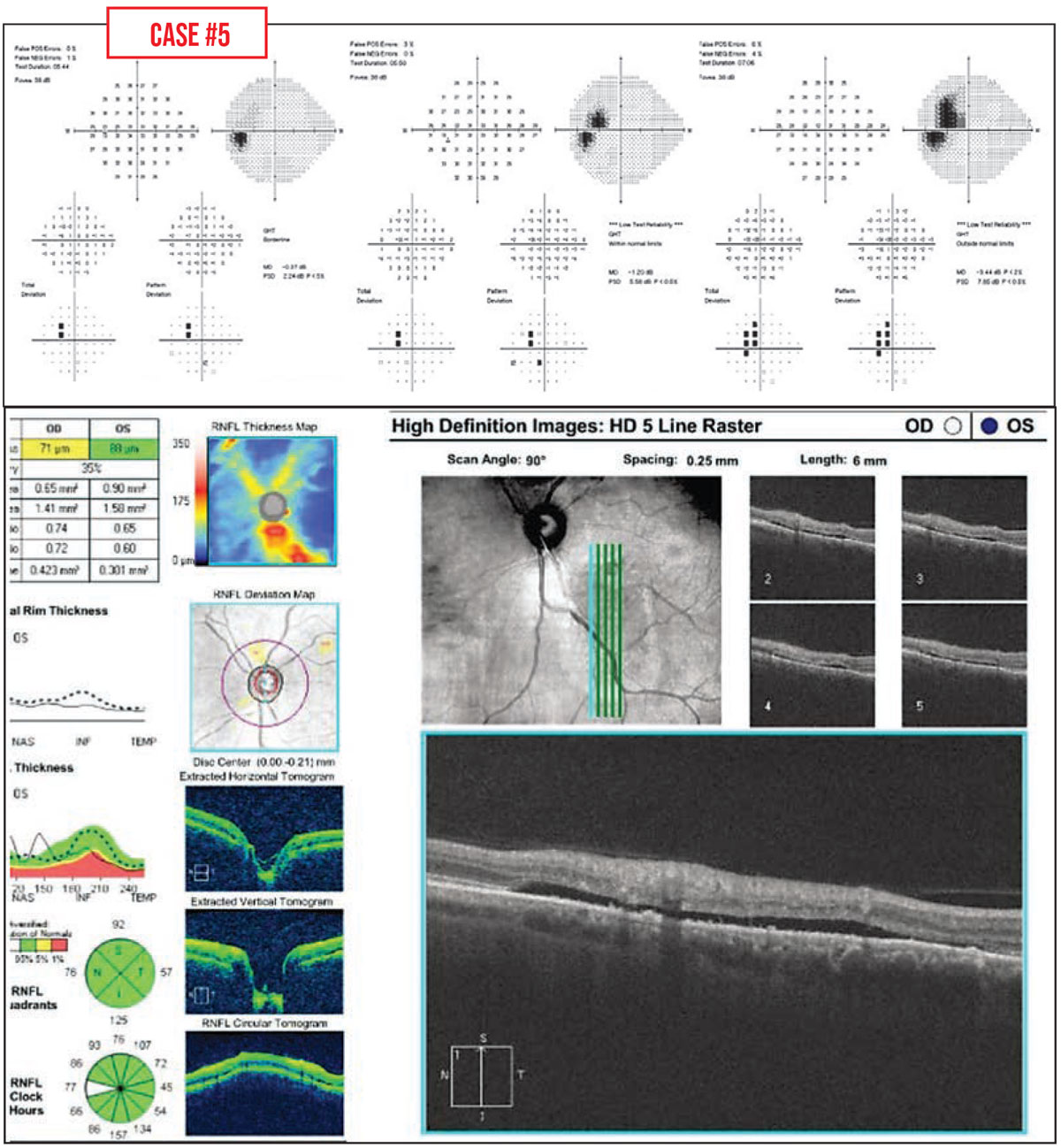

Case #5: This patient had a healthy optic nerve, but an enlarging field defect was noted. The problem was central serous retinopathy. A subsequent field showed a decrease in the size of the defect over time, which corresponded to a reduction in subretinal fluid.

|

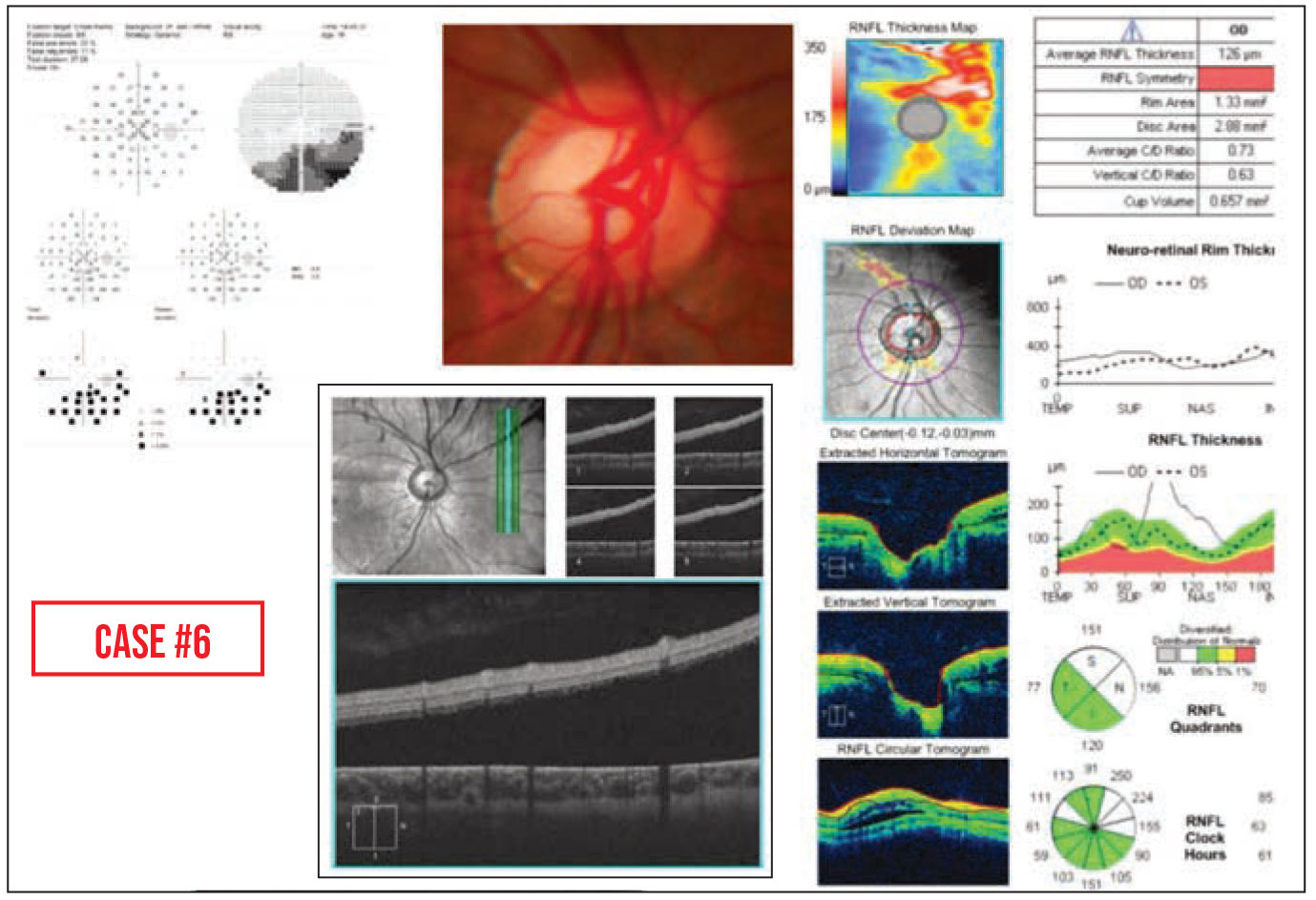

Case #6: This teenager with an inferior arcuate defect was referred for possible glaucoma. However, subretinal fluid was noted on the peripapillary RNFL OCT. This revealed a previously undiscovered, low-lying retinal detachment.

|

One other situation is worth mentioning. Sometimes a patient will have both advanced glaucoma and retinal dystrophy, making it very difficult to determine which disease is causing vision deterioration. In this situation, optimizing IOP control, consultation with an experienced retina specialist, and possible serial electroretinogram testing could be helpful for determining the relative contributions of these two entities to any progressive vision loss.

Strategies for Success

Here are a few strategies that can help you distinguish glaucoma progression from retinal disease:

• Obtain baseline testing data. Change over time may be key to determining whether glaucoma is present and whether there’s any glaucoma progression. Performing a variety of tests at baseline allows for comparisons to be made over time, which can be helpful for distinguishing between real glaucoma progression and retinal disease.

• Don’t rely on a single type of test for following glaucoma patients. Some test modalities are better suited for following glaucoma progression in certain patients. OCT can be very useful for assessing progression in glaucoma patients who have yet to develop glaucomatous visual field defects, but for high myopes, visual field testing can provide more useful information than OCT. If macular pathology is present, peripapillary RNFL OCT scans may be more helpful. Baseline testing can help you determine which tools may be most useful for monitoring a particular patient.

• Check for structure-function correlation between the optic nerve examination, visual field and OCT. Agreement or disagreement can assist in resolving ambiguities, since there should be correspondence between the location of structural thinning on the optic nerve and functional visual field defects.

• Closely inspect peripapillary RNFL OCT B-scans and macular OCT scans. We sometimes focus primarily on the quantitative values seen on scans, but examination of the actual peripapillary RNFL and macular OCT scans themselves can help identify possible artifacts and retinal pathology.

• Remember that visual field defects associated with retinal disease tend to be deep, and often don’t respect the horizontal midline. Some artifacts may resemble typical glaucomatous damage, but atypical visual field defects provide a strong clue that something other than glaucoma may be responsible. Retinal abnormalities tend to cause very deep defects with sharp borders that often don’t respect the horizontal midline on visual field testing.

• If change isn’t occurring over time, glaucoma progression probably isn’t the cause of the abnormal test data. As a general rule, even if baseline test results are markedly abnormal, if the results don’t change over time and the patient reports stable visual function, the glaucoma probably isn’t worsening.

• Your tech may catch something you overlooked. Sometimes a retinal detachment is hard to see when it’s low-lying, as in Case #6 above. In this case, several eye-care providers had seen the patient and not noticed a retinal detachment. In our clinic, we ordered a peripapillary RNFL OCT prior to performing our dilated eye exam, as we usually do for glaucoma evaluation. The technician said, “This doesn’t look right to me. There’s fluid under the retina that shouldn’t be there.” So she did some additional scans and found the retinal detachment. She was the one who actually picked it up.

• If you can’t determine whether the patient has glaucoma, consider treating for it. In some cases, you’re not certain the patient actually has glaucoma. This can be particularly challenging if you know the patient already has another vision-threatening condition such as proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Maybe their eye pressure isn’t very high, but their nerves look a little suspicious. I’ll often discuss with the patient whether they’d like to be treated, just in case they do have glaucoma, because they’re already at such high risk of vision loss.

Of course, glaucoma treatment can be a long-term burden with a major impact on quality of life, so it’s important to discuss options with each patient and tailor management to the patient’s preferences. I might say, “We’re not sure whether or not you have glaucoma. But given that you already have a condition that’s putting you at risk of severe vision loss, would you like to be proactive and be treated for possible glaucoma?” Many times, patients will say yes. At the same time, many patients will say they don’t want to be treated for something we’re not sure they have. So you have to assess the patient’s priorities and what level of risk they’re comfortable with.

• When in doubt, consult with glaucoma and retina colleagues. They can be very helpful when assessing the relative contributions of glaucoma and retinal disease in patients with progressive vision loss caused by these coexisting ocular conditions.

Making the Best of It

Differentiating glaucoma and retinal conditions can be challenging. Sometimes, even with all the tests and all of the experience you’ve accumulated, you still may not be sure if the glaucoma is getting worse or vision loss is occurring because of retinal disease. Discuss the case with your glaucoma and retina colleagues and then make the best decision you can. The reality is, it’s not always possible to differentiate these conditions with 100-percent certainty.

Nevertheless, many patients are referred because the doctor has concluded that the patient’s glaucoma must be getting worse: “Just look at these terrible test results!” However, a detailed history and examination may uncover an alternate cause. So it’s important to take into consideration that retinal diseases and procedures can affect test results used in glaucoma evaluation.

Whenever you see a major change in the test data, or a glaucoma patient comes in with a new visual complaint, be aware that a retinal problem could very well be the cause—and do your best to navigate the wisest path forward.

Dr. Liu is an assistant professor in the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at the School of Medicine and Public Health, at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She reports no financial ties relevant to this article.

1. Liu Y, Baniasadi N, Ratanawongphaibul K, Chen TC. Effect of partial posterior vitreous detachment on spectral-domain optical coherence tomography retinal nerve fibre layer thickness measurements. Br J Ophthalmol 2020;104:11:1524-1527.

2. Asrani S, Essaid L, Alder BD, et al. Artifacts in spectral-domain optical coherence tomography measurements in glaucoma. JAMA Ophthalmol 2014;132:4:396-402.

3. Garas A, Papp A, Holló G. Influence of age-related macular degeneration on macular thickness measurement made with fourier-domain optical coherence tomography. J Glaucoma 2013;22:3:195-200.