Presentation

A 31-year-old male presented to the emergency room with a one-week history of progressively worsening painless vision loss in the right eye. The left eye was asymptomatic. He denied headaches, pain with extraocular movements, or light sensitivity. He denied history of aphthous ulcers, genital ulcers or cold sores.

|

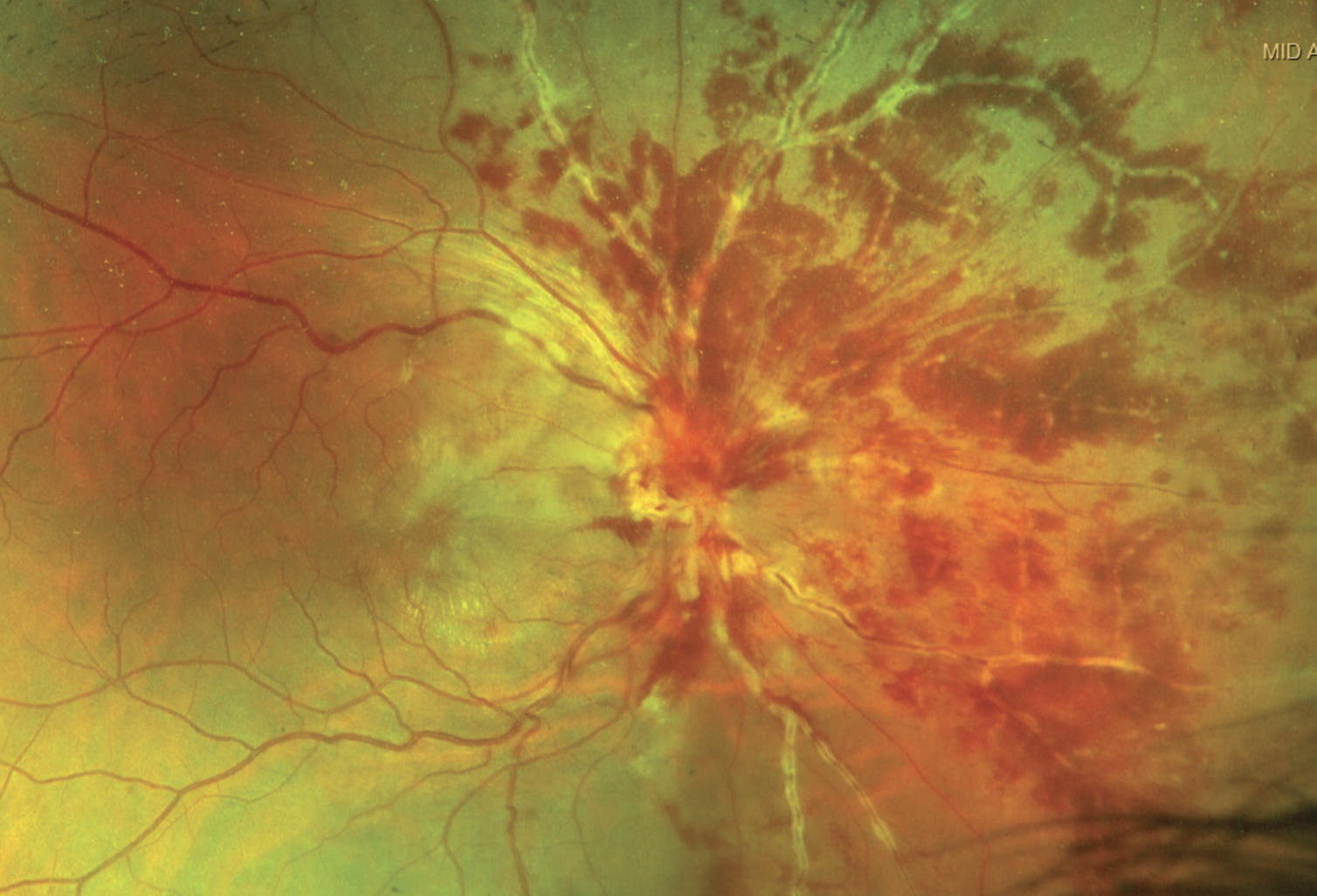

| Figure 1. The fundus exam of the right eye found significant disc and peripapillary hemorrhages that obscured the optic disc. |

Medical History

The patient denied any past ocular, medical or surgical history. The patient was a refugee from Afghanistan and was settled in a refugee camp. He denied any history of intravenous drug use. He reported a recent episode of unprotected sex approximately nine months prior but had never been tested for any sexually transmitted infections. The remainder of his review of symptoms was negative.

Examination

Visual acuity was Count Fingers at 4 feet in the right eye and 20/20 in the left. There was a 1+ relative afferent pupillary defect in the right eye. On confrontational visual fields, the right eye was globally depressed and the left eye was normal. Extraocular motility was full. Intraocular pressures were normal. On anterior exam, the conjunctiva and sclera were white and quiet in both eyes. Both corneas were clear without keratic precipitates. The anterior chamber was deep and quiet bilaterally. He had no iris abnormalities, and his lenses were clear. The right anterior vitreous had 1+ cell, and the left anterior vitreous was clear. The fundus exam of the right eye was notable for significant disc and peripapillary hemorrhages that obscured the optic disc (Figure 1). The macula demonstrated hard exudates in a macular star configuration. The vessels had notable perivenular sheathing that appeared localized primarily to the nasal retina. Inferiorly, abnormal vessels appeared to extend into the vitreous, suspicious for neovascularization elsewhere (NVE). There were extensive intraretinal hemorrhages that were also localized to the nasal retina. There was no evidence of retinal whitening. The fundus exam of the left eye revealed clear media, sharp disc margins without elevation or hemorrhages, vessels with normal caliber and without sheathing, a flat macula with no exudates and with a good foveal reflex, and a normal periphery with no evidence of intraretinal hemorrhages or retinal whitening.

What is your diagnosis? What further work-up would you pursue? The diagnosis appears below.

Work-up, Diagnosis and Treatment

The differential diagnosis for retinal vasculitis is broad and includes infectious etiologies, inflammatory disorders, drug reactions and malignancies. Some of the more common causes of a retinal phlebitis include Behcet’s disease, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, pars planitis, Eales’ disease, multiple sclerosis and CMV retinitis. Our patient subsequently underwent an anterior chamber paracentesis for PCR testing as well as intravitreal foscarnet injection to treat a potential viral retinitis. Labs collected included CBC, BMP, ESR, CRP, ANA, Lyme antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, Bartonella IgG/IgM antibodies, syphilis antibodies, QuantiFERON gold, ACE, ANCA panel and chest X-ray.

|

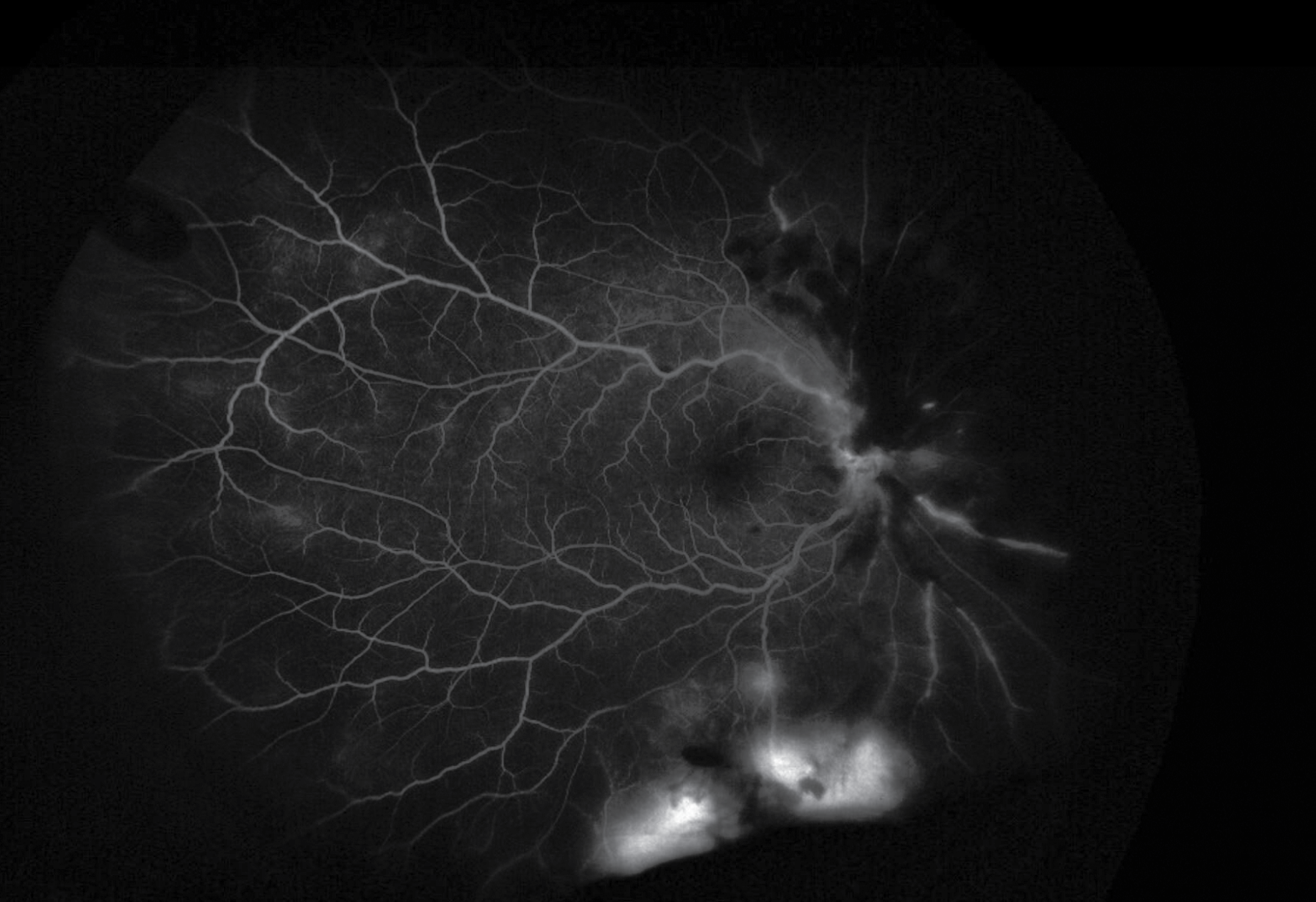

| Figure 2. Late frames on FA demonstrated inferior leakage with surrounding non-perfusion suggestive of neovascularization elsewhere. |

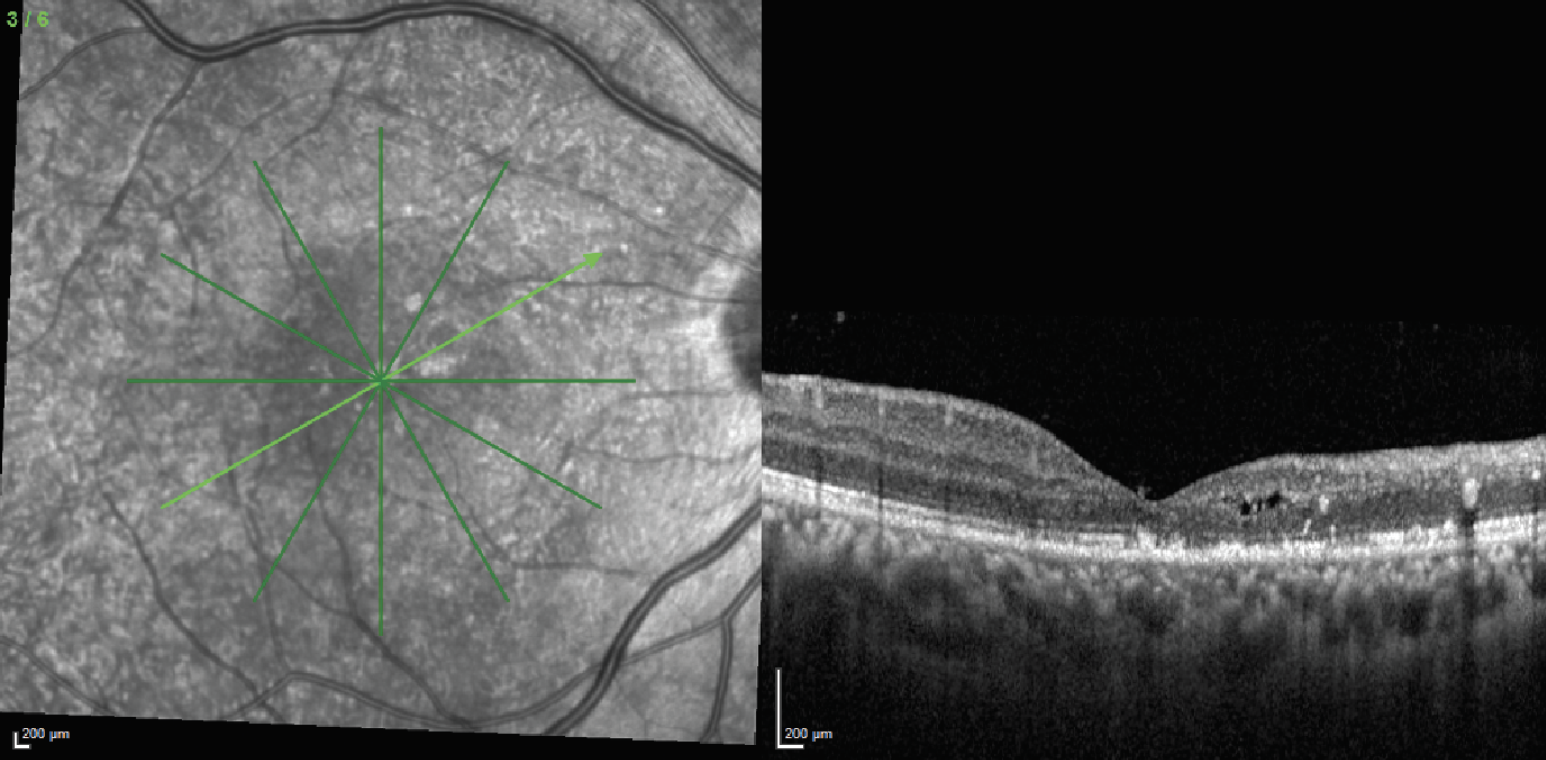

A fluorescein angiography was performed the following day. During the arteriovenous phase there appeared to be significant blockage nasally from the intraretinal hemorrhages of the right eye. The venous phase demonstrated marked hypoperfusion nasally and inferiorly. Late frames demonstrated inferior leakage with surrounding non-perfusion suggestive of NVE (Figure 2). The FA of the left eye was within normal limits. OCT of the right eye demonstrated vitreous debris consistent with vitreous cell, disruption of the normal laminations of the retina, intracystic changes and disruption of the ellipsoid zone layer (Figure 3). OCT of the left macula was normal.

Laboratory testing revealed a positive QuantiFERON test but was otherwise negative. The ocular PCR panel was negative for HSV-1/2, VZV, CMV and Toxoplasma gondii. The patient was diagnosed with tuberculous retinal vasculitis and was started on anti-tuberculous therapy including rifampin, isoniazid, ethambutol and pyrazinamide. At one month follow-up, the acuity was stable at count fingers OD. Funduscopic exam showed interval improvement in the peripapillary and intraretinal hemorrhages with consolidation of the macular star. The disc was visible with evidence of neovascularization of the disc. Repeat FA of the right eye showed NVD and NVE with persistent areas of non-perfusion inferiorly and nasally, as well as persistent albeit improved blockage from the intraretinal hemorrhages.

|

| Figure 3. OCT of the right eye demonstrated vitreous debris consistent with vitreous cell, disruption of the normal laminations of the retina, intracystic changes and disruption of the ellipsoid zone layer. |

Discussion

There remains no solid data to indicate the true prevalence of ocular tuberculosis. This primarily stems from the lack of uniform and universal diagnostic criteria for the disease.1 Ocular TB can present in a variety of ways involving different segments of the eye. In the anterior chamber, TB can present as a chronic granulomatous anterior uveitis.1 Clinical features include posterior synechiae (“sticky uveitis”), mutton fat keratic precipitates and granulomas in the iris and angle.1 The disease can also present as intermediate uveitis with vitritis, snowballs and snow-banking.1 Posterior uveitis secondary to TB can present in a variety of ways. A common clinical presentation is the development of choroidal tubercules. These small yellowish-grey nodules with poorly demarcated margins can be found in one or both eyes.1 Another common finding is choroidal tuberculomas, which are large yellowish subretinal lesions that are associated with subretinal fluid and can lead to exudative retinal detachments. These lesions can evolve into subretinal abscesses that can result in liquefactive necrosis.1 Ocular TB can also present as a serpiginous-like choroiditis with lesions starting in the peripapillary region and spreading centrifugally.1

A less common presentation of ocular TB is retinal vasculitis. The disease appears to most often affect younger patients, males and patients of an Asian background.2 The vasculitis typically involves the retinal veins but spares the arteries. Findings on exam include perivenous sheathing and intraretinal hemorrhages localized to one sector of the retina.3,4 This may be complicated by inflammatory vascular occlusion leading to capillary non-perfusion.3 The non-perfusion may be further complicated by neovascularization with recurrent vitreous hemorrhages. Iris neovascularization and neovascular glaucoma can also be observed.3 Another important clinical feature is the presence of vitritis, which can help differentiate TB retinal vasculitis from Eales’ disease.3 The diagnosis is dependent on a positive tuberculin skin or an interferon gamma releasing assay such as the QuantiFERON Gold Plus or TB Spot tests. Differentiating between TB retinal vasculitis and Eales’ disease is necessary as the former requires specific anti-tuberculous therapy.

Management involves work-up for active systemic TB as well as combination antibiotic therapy. Work-up should include a chest X-ray or chest CT scan to assess for active or inactive lesions suggestive of TB, although negative radiographic imaging doesn’t rule out the diagnosis.1,3,5 Treatment involves administration of anti-TB therapy which should include a combination of isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol for two months followed by isoniazid and rifampin for four months (although there are different combination therapies that are also acceptable). In the absence of systemic infection with mild peripheral vasculitis in an asymptomatic patient, treatment may be deferred at the discretion of the provider with close follow-up to ensure no progression of the disease.3 A consensus statement on the management of retinal vasculitis has been published as part of the Collaborative Ocular Tuberculosis Study.6

Patients with TB retinal vasculitis may also need adjuvant steroids. The addition of steroids is meant to tackle the host immune component of the disease. This is particularly important in cases of paradoxical worsening of the disease after the administration of anti-tuberculous therapy.3

In addition to systemic workup, further evaluation of the retina with multi-modal imaging is warranted. Fluorescein angiography typically demonstrates perivenular leakage at the sites of active inflammation, often with neovascularization of the disc, neovascularization elsewhere and areas of capillary non-perfusion.3 This can guide therapy such as when to begin intravitreal anti-VEGF injections or panretinal photocoagulation. OCT of the macula can identify complications such as cystoid macular edema. A vitreous tap followed by PCR testing of the aspirate for TB would be ideal and would confirm the diagnosis; however, this isn’t clinically available in the United States and suffers from low sensitivity.7 Our patient began to show clinical improvement shortly after initiating anti-TB treatment. The prognosis, however, remained guarded given his extensive non-perfusion and optic nerve involvement.

In summary, TB retinal vasculitis is one of the many manifestations of ocular TB. The diagnosis doesn’t require a prior systemic infection. It typically involves the retinal veins but not the arterioles, helping to distinguish it from acute retinal necrosis or Behcet’s disease. Other clinical features include vitritis, capillary non-perfusion, neovascularization and vitreous hemorrhage. Management involves a systemic workup for active TB, although it’s frequently absent. Treatment includes anti-tuberculous therapy to target the infection and corticosteroids to mitigate damage secondary to the inflammatory reaction. Treatment should also be geared toward treating the complications of the vasculitis and should include intravitreal anti-VEGF and panretinal photocoagulation for capillary non-perfusion and neovascularization.

1. Gupta V, Gupta A, Rao NA. Intraocular tuberculosis--An update. Surv Ophthalmol 2007;52:561–587.

2. Agrawal R, Gunasekeran DV, Gonzalez-Lopez JJ, et al. Peripheral retinal vasculitis: Analysis of 110 consecutive cases and a contemporary reappraisal of tubercular etiology. Retina 2017;37:112–117.

3. Shukla D, Kalliath J, Dhawan A. Tubercular retinal vasculitis: Diagnostic dilemma and management strategies. Clin Ophthalmol Auckl NZ 2021;15:4681–4688.

4. Patricio MS, Portelinha J, Passarinho MP, Guedes ME. Tubercular retinal vasculitis. BMJ Case Rep 2013;2013:bcr2013008924.

5. Patel SS, Saraiya NV, Tessler HH, Goldstein DA. Mycobacterial ocular inflammation: Delay in diagnosis and other factors impacting morbidity. JAMA Ophthalmol 2013;131:752-8.

6. Agrawal R, Testi I, Bodaghi B, et al; Collaborative Ocular Tuberculosis Study Consensus Group. Collaborative Ocular Tuberculosis Study consensus guidelines on the management of tubercular uveitis-report 2: Guidelines for initiating antitubercular therapy in anterior uveitis, intermediate uveitis, panuveitis, and retinal vasculitis. Ophthalmology 2021;128:2:277-287.

7. Wroblewski KJ, Hidayat AA, Neafie RC, et al. Ocular tuberculosis: A clinicopathologic and molecular study. Ophthalmology 2011;118:4:772e777.