Accidents happen, but they may be happening more among glaucoma patients. Most glaucoma patients don’t notice their gradual peripheral field loss and continue to drive since they retain good central vision. However, we see in the literature that even small amounts of peripheral field loss can hinder safe driving. Do you and your patients know their driving risk and whether they meet their state’s vision requirements for driving?

At the same time, there are plenty of other factors that might make someone unsafe to drive that have nothing to do with their vision, some of which ophthalmologists don’t typically assess. Cognitive issues, processing speed, executive function, planning ability, reaction time, coordination and cellphone use may all come into play. Other drivers also pose a potential threat. So, when and how should you tell a patient to hang up the keys?

Here, I’ll review visual requirements for driving, what we know about glaucoma patients’ on-road performance and discuss how I approach the inevitably difficult conversation with the patient.

State Driving Regulations

Vision requirements for driving vary considerably across the United States, so it’s helpful for ophthalmologists to know their state’s regulations. Many states set minimum visual acuity at 20/40, which is also how low-vision is defined by the National Institutes of Health. Other states require at least 20/100 visual acuity for some driving, which falls within the World Health Organization’s low-vision definition of visual acuity between 20/60 and 20/200. Most requirements specify whether the visual acuity listed is for one or both eyes and/or include certain restrictions for poorer vision such as daytime-only driving or avoiding freeways.

Visual field requirements for driving in the United States may range anywhere from 55 to 150 degrees. Some states don’t have minimum visual field requirements or require vision testing for license renewal. As a quick reference, you can find a table of vision restrictions for noncommercial licensure at eyewiki.aao.org/Driving_Restrictions_per_State. As you might surmise, vision requirements for commercial licensure are much stricter.

Most of these vision requirements for driving weren’t written by ophthalmologists. Perhaps that’s a good thing given our limited experience writing legislation, but on the flip side, many of the state regulations fail to specify important details. What does it mean to say that Tennessee drivers, for example, are required to have a “visual field diameter of no less than one hundred fifty (150) degrees without the use of field expanders…”? Is that 150 degrees continuous? Is that 150 degrees in which you can make out a large object, or 150 degrees in which you can make out a small stimulus? Additionally, most states don’t specify the vertical component, just the left-right horizontal component. Is driving with a complete altitudinal defect acceptable?

The state requirements are also often silent on the question of how we establish the field of vision. They don’t specify the stimulus size or defect depth. There are customary ways that people perform the testing, but the type of test isn’t usually specified in the requirements. One customary way is to use the Goldmann kinetic perimetry stimulus III-4e as a criterion, but few of us are routinely using Goldmann perimetry. On the other hand, static perimetry such as the Humphrey Visual Field Analyzer is widespread. A 10-decibel stimulus on the Humphrey would be somewhat analogous to missing the Goldmann III-4e—that’s about a 20-dB defect in the central field. So, it’s a fairly decent-sized defect that counts for the purposes of driving. It’s not just a mild depression but a pretty solid loss at one or several points in that area.

Field Loss & Car Accidents

Though the absolute risk of having an accident in a given year is fairly small for most drivers, real-world data shows that this risk is greater among glaucoma patients. Cynthia Owsley, MD, and colleagues have been researching the impacts of aging on vision for a number of years. One of the groups’ studies investigated motor vehicle collision risk among 2,000 licensed drivers in Alabama, aged ≥70 years.1 They found that glaucoma patients (n=206) had more actual collisions (1.65 times higher MVC rate [95% CI, 1.2 to 2.28; p=0.002]) and that patients with impaired left visual fields were more likely to have been involved in an accident (risk ratio: 3.16; p=0.001; mean sensitivity <22 dB).

A study by Balwantray Chauhan, PhD, and colleagues examined on-road driving performance among glaucoma patients (n=20; better-eye MD -1.7 dB; worse-eye MD -6.5 dB; all ≥20/40, ≥120 degrees VF) vs. controls (n=20).2 All of these glaucoma patients would generally be considered legal to drive based on their visual field loss—they all have reasonably good central and peripheral vision. The better eyes had very mild defects and the worse eyes had moderate defects, on average. Even though they meet the legal requirements for driving and had one eye that was very good, these glaucoma patients were still three times more likely to have incidents requiring intervention by the person riding alongside (a professional driving instructor) in this on-road test. After adjusting for age, sex, medications and driving exposure, the glaucoma patients were up to six times more likely to require intervention because of a mistake—predominantly failure to see and yield to a pedestrian, peripheral obstacles and reaction to unexpected events.

In another on-road study, Dr. Owsley and her team investigated types of driving errors linked to glaucoma. This study found that older drivers (n=75; mean age 73.2 ±6 years) with mild to moderate field loss (better-eye MD -1.21 dB; worse-eye MD -7.75 dB; all ≥20/40, ≥110 degrees VF) had some driving ability impairments, particularly with lane position, planning ahead and observation (e.g., traffic lights).3 These patients were 1.93 times more likely than controls to require intervention. In self-reported driving assessments, most patients considered their own driving to be relatively good.

The authors hinted that there may be additional issues besides vision at play. Glaucoma is more common as we age, so some of these concurrent issues such as cognition speed and processing may make driving more challenging or less safe. In fact, a driving simulation study published in BMC Ophthalmology in 2020 reported that glaucomatous visual fields and neurocognitive function are independently associated with poor lane maintenance.4

In simulator studies, glaucoma patients are also more likely to have accidents.5 A study in Japan noted that though the severe glaucoma patient participants (n=95) had good central vision (20/25 in the better eye), the better eye had a lot of field loss (MD -18 dB).6 Collision involvement was significantly associated with decreased inferior visual field mean sensitivity in the mid periphery from 13 to 24 degrees (p=0.041), older age and lower visual acuity (p=0.018 and p=0.001).

As part of a study we presented as a poster at the 2019 ARVO Meeting in Vancouver testing glaucoma patients’ performance on real-world tasks such as identifying misspelled words and matching pairs of socks, we also asked patients if they’d been involved in any accidents in the past five years. Indeed, the glaucoma patients were about twice as likely to be involved in self-reported motor vehicle collisions than average for similarly aged healthy drivers.

Overall, we find in the literature that field loss is linked to accidents, particularly inferior and left visual field loss. This makes sense as most of the threats on the road come from the left in our country. The car that’s going to hit you first at an intersection comes from the left side. Can your patient see someone who runs a stop sign?

|

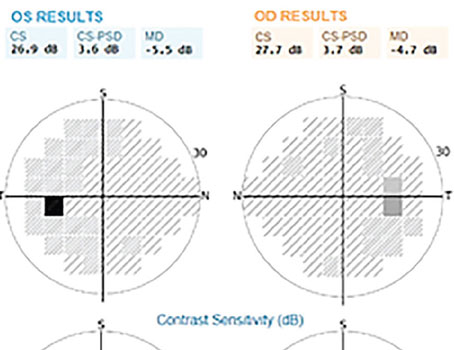

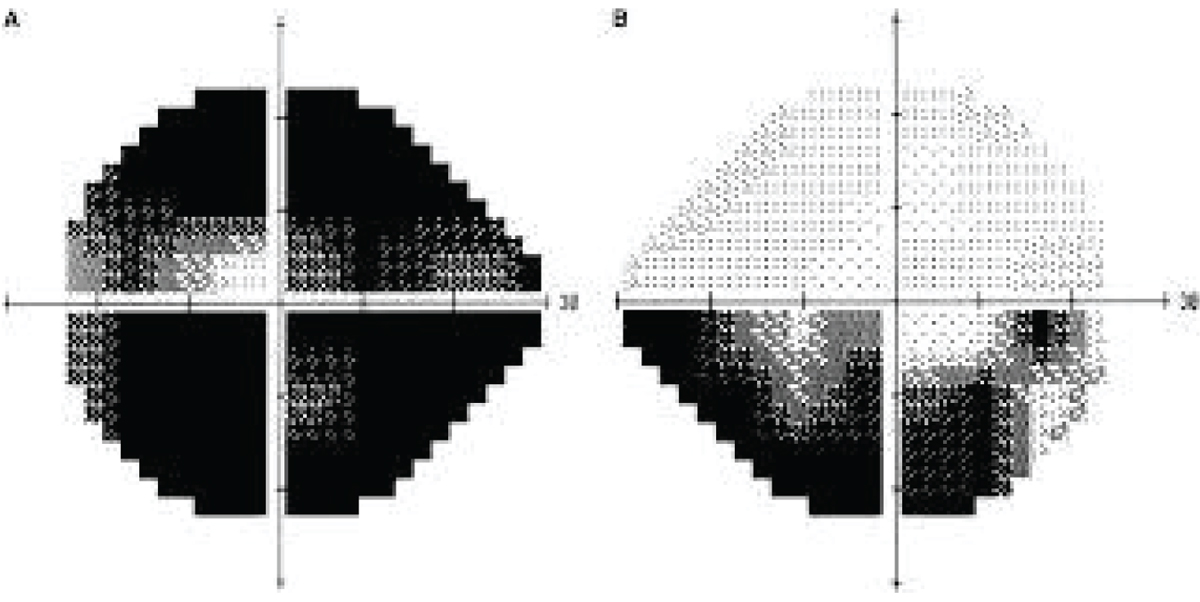

| Patient 1 has a fairly typical glaucoma field. Much of the field loss in one eye is reinforced by areas of seeing in the other. The field loss in these two eyes doesn't overlap in space. |

Detecting A Problem

Considering the literature, how comfortable would you be telling the following patients whether or not they can drive?

Patient 1 (see image above) has a fairly typical glaucoma field, mainly superonasal steps with moderate superior arcuates that are primarily nasal. In this case, much of the patient’s field loss in one eye is reinforced by areas of vision in the other eye, so the field loss in these two eyes isn’t overlapping in space. This is a patient who may well be okay to drive. I’d counsel this patient about the increased risk of accidents, but I’d also tell them that in most states, they meet the legal requirements to drive if they don’t have other comorbidities.

|

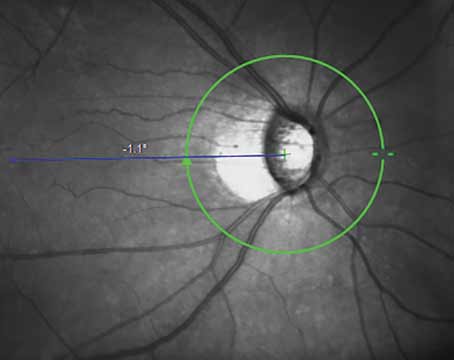

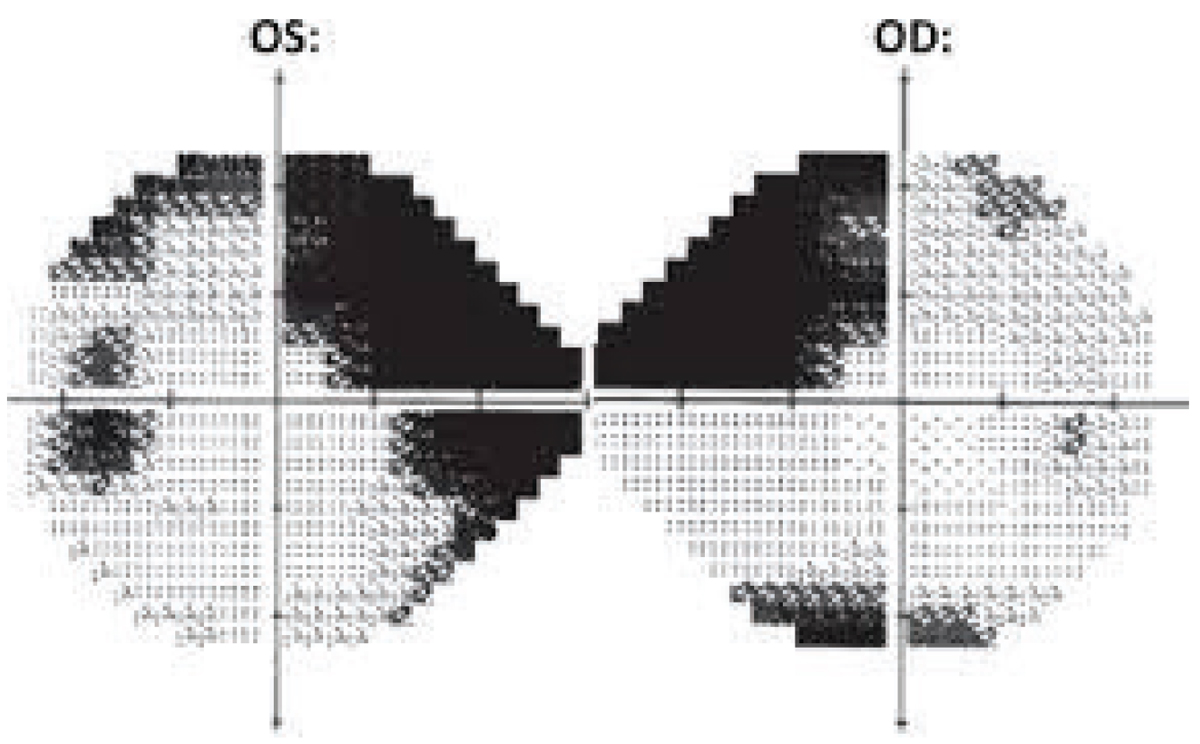

| Patient 2 has complete left-sided field loss in both eyes, such as from a stroke. |

Patient 2 (see image above) has a homonymous hemianopsia on the left, i.e., complete left-sided field loss in both eyes such as from a stroke. They have a lot of preserved field to the right, and in some states, with vision rehabilitation and occupational therapy, they may be able to drive legally. However, that’s not my area of expertise.

In many areas there are organizations that offer driver therapy or occupational therapy, including formal driving testing and rehabilitation programs. Internet searches turned up many of these programs. I think it’s great to refer patients like this case example who may be able to drive safely with some professional help.

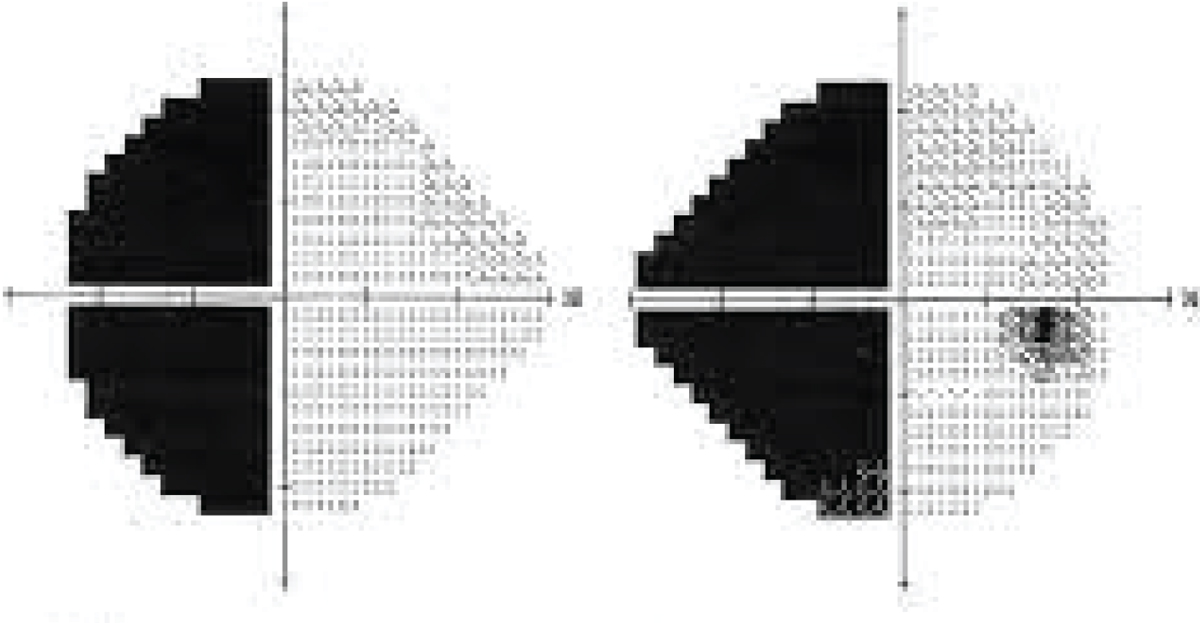

Patient 3 (see image below) has more advanced glaucoma fields with a central island of vision in the left eye and a fairly dense arcuate in the right eye that approaches central fixation. This patient has several of the risk factors, including overall field loss, that the previously mentioned studies suggest puts them at greater risk for accidents. This patient’s field loss overlaps leftward and downward. Whether they meet the legal requirements in their state or not—I’m not sure I’m comfortable saying that this patient will be okay to drive.

|

| Patient 3 has more advanced glaucoma fields with a central island of vision in the left eye. |

State restrictions usually specify that the patient meet requirements in the horizontal meridian. This patient’s defect goes right up to the meridian, but we don’t generally test on the meridian itself. That creates more uncertainty.

Apart from the visual findings, what else can clue you in that a patient may need to give up their keys? While ophthalmologists certainly aren’t neurocognitive specialists, you may notice a patient having difficulty following a conversation during the exam. A patient may mention in passing some driving incident that occurred. These may prompt you to think about whether the patient is safe behind the wheel.

I’ve also found that family members can be great resources for providing insight on your patients. Involving them in conversations, if they accompany the patient to the exam or if the patient gives you permission to call them, may reinforce any potential discussion, and family members can also help the patient navigate the web and find driving rehabilitation and low-vision resources (more on that below). Many times, I’ve had patients go into an exam room, and the trailing family member says to me softly, “I don’t think my mom’s safe to drive.” That’s not at all uncommon. Family members will occasionally tip you off. They don’t want to be the “bad guy,” and that’s totally reasonable to me, especially since they aren’t the expert that can answer this question.

Are You Ready for the Talk?

Patients will be understandably distraught at being told they should alter their driving habits or perhaps stop driving altogether. Naturally, these conversations are challenging and emotionally charged. No patient goes to the doctor wanting to be told they shouldn’t drive. The discussion involves not just questions of logistics for the patient and the inconvenience, but also how patients view themselves as independent people. It brings up issues of personhood and personal freedom, which I sympathize with.

In general, ophthalmologists in residency aren’t trained in great detail about having hard conversations. One book I’ve found useful in my practice is Difficult Conversations.7 It’s one of many resources that focus on how to have these discussions. Some takeaways I’ve gleaned include beginning conversations without defensiveness, listening for the meaning of what the patient isn’t saying, staying balanced in the face of attacks and accusations and moving from emotion to productive problem solving. Easier said than done. However, keeping these in mind may make these discussions go smoother, which is beneficial for everyone involved.

As far as timing goes, my own experience talking with patients suggests that conversations about driving are best undertaken gradually. Having the full conversation in a single day can be very challenging. Some patients just aren’t able to process it all or they stop processing once they hear the bad news.

I’ve found I haven’t had a lot of success convincing patients not to drive just by saying it’s the law. I often mention my concerns for their own physical wellbeing—notably, elderly drivers are more likely to be fatally injured in a crash than younger drivers. However, I find that doesn’t often change minds. I live in Pennsylvania, where there’s a lot of litigation, so I often bring up the idea of lawsuits to patients. I point out that even if they were involved in an accident that wasn’t their fault, but someone got wind of the fact that they had vision issues, that person might try to make their lives difficult from a legal perspective. That, I think, starts to turn heads because people fear lawsuits, often with good reason.

Sometimes, I’ll mention that, depending on where you live, the doctor may be legally required to report patients who don’t meet the state’s requirements for driving. I don’t think it’s at all common for an ophthalmologist to get in trouble in this regard, though I’m not an expert on case law. In general, it’s good to follow legal guidelines when possible. If a patient commits to me that they’re not going to drive, and I find that credible, I document that conversation in the chart and that they’re not going to drive. Documentation always helps.

If I’m truly concerned that a patient is still driving, and I think they truly present a risk to others, I show them their visual field loss on a screen and point out that a small child could fit within that field loss. I don’t want to be mean to patients, but I also want to help them understand that my true concern is not just for them, but for everyone else. I think it helps patients consider that they have an obligation to society. If that doesn’t move the patient—that they may be putting others in harm’s way—sometimes that moves me to report them, but it’s very uncommon in my practice for that to be necessary. Most patients understand and are reasonable.

Some doctors may argue that this gets into the question of their responsibility being only to the patient. While we have a commitment to the patient in front of us, that same patient who I’m committing to may run over one of my other patients in the waiting room on their way out of the parking lot. So, I feel we have a societal responsibility not to let unsafe situations persist.

Help Is Out There

Vision loss doesn’t necessarily mean an end to driving outright. Many states allow those with a certain level of low vision to drive, with some restrictions such as using only secondary roads, not driving during rush hour or on crowded roads, driving only between the hours of 10:00 AM and 2:00 PM or driving only a certain number of miles.

Here are some options for your patients:

- Occupational therapy. Patients may need support from practitioners in other fields. Occupational therapy or driver rehabilitation can help certain patients learn to drive safely, and if driving is no longer possible, at least the patient will have that knowledge.

- Bioptic telescope lenses. If the patient’s state allows this device for driving, bioptic telescope lenses may offer a way to continue driving safely. Pennsylvania recently established a training program and licensing process for individuals to use bioptic telescope lenses to meet the visual acuity standards for driving. According to PA law, individuals with visual acuity less than 20/100 combined but at least 20/200 in the best-corrected eye are eligible to apply for a bioptic telescope learner’s permit.8

- Uber, Lyft and other ride-share programs. These options may present financial and logistical challenges for elderly drivers, but they can help patients get to appointments, the market and their social engagements.

- Paratransit. This provision is available through the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990: Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. It’s not always fast or convenient, but it’s often an affordable and effective option.

It may be helpful for patients’ recollection after the conversation to keep a printed list of the vision requirements for driving in your state handy, as well as a list of low vision or occupational therapy specialists (state programs are often very good), driver rehabilitation programs, alternative transportation options and social workers in your area.

Final Thoughts

Glaucoma increases the risk of being involved in a car accident, especially for patients over the age of 75. That doesn’t mean your patients shouldn’t drive, but they should be made aware of the increased risk, which is present even in patients without severe field loss, and that extra care on the road may be required.

Dr. Singh is a professor of ophthalmology and chief of the Glaucoma Division at Stanford University School of Medicine. Dr. Netland is Vernah Scott Moyston Professor and Chair at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Dr. Myers is chief of the Wills Eye Glaucoma Service and a professor of ophthalmology at Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

1. Kwon MY, Huisingh C, Rhodes LA, et al. Association between glaucoma and at-fault motor vehicle collision involvement among older drivers: A population-based study. Ophthalmol 2016;123:1:109-116.

2. Haymes SA, Le Blanc RP, Nicolela MT, et al. Glaucoma and on-road driving performance. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2008;49:7:3035-3041.

3. Wood JM, Black AA, Mallon K, et al. Glaucoma and driving: On-road driving characteristics. PLoS One 2016;11:7:e0158318.

4. Anderson DE, Bader JP, Boes EA, et al. Glaucomatous visual fields and neurocognitive function are independently associated with poor lane maintenance during driving simulation. BMC Ophthalmol 2020;20:419. [Epub October 20, 2020].

5. Szlyk JP, Mahler CL, Seiple W, et al. Driving performance of glaucoma patients correlates with peripheral visual field loss. J Glaucoma 2005;14:2:145-150.

6. Kunimatsu-Sanuki S, Iwase A, Araie M, et al. The role of specific visual subfields in collisions with oncoming cars during simulated driving in patients with advanced glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 2017;101:7:896-901.

7. Stone D, Patton B, Heen S. Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most. New York: Penguin Books, 2000.

8. Fishman, K. New PA license program changes game for visually-impaired drivers. Patch: Pennsylvania. https://patch.com/pennsylvania/across-pa/new-pa-license-program-changes-game-visually-impaired-drivers. Accessed September 23, 2022.